Objective and Subjective Factors Influencing Breast Reconstruction Decision-Making After Breast Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Criteria

2.4. Study Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis and Analysis

2.6. Study Design

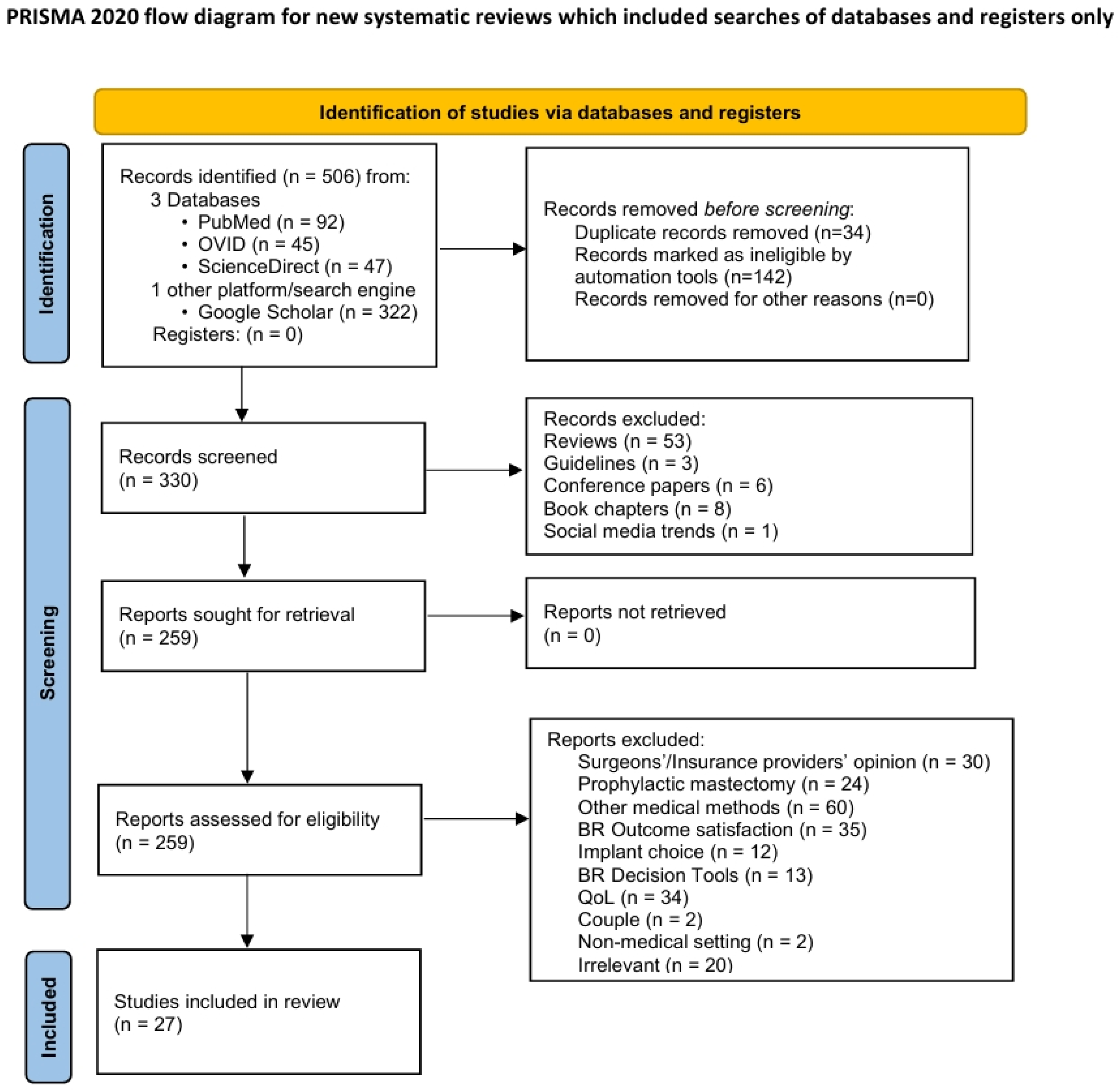

Identification and Screening

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Studies Included

3.2. Demographic and Clinical Information

3.3. Factors Influencing BR

3.3.1. Objective Factors

- Age

- 2.

- Socioeconomic reasons

- 3.

- BR awareness and source of information

- 4.

- Medical reasons

- 5.

- Physician recommendation/influence

- 6.

- Role of partner

- 7.

- Education

- 8.

- Race

3.3.2. Subjective Factors

- Body image and self-esteem

- 2.

- Fear of recurrence

- 3.

- Concerns about additional surgery/hospitalization

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BR | Breast reconstruction |

| SDM | Shared decision-making |

| QuADS | Quality Appraisal for Diverse Studies |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| IBR | Immediate breast reconstruction |

| PMRT | Post-mastectomy radiation therapy |

| DBR | Delayed breast reconstruction |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

| nBR | No breast reconstruction |

References

- Caswell-Jin, J.L.; Sun, L.P.; Munoz, D.; Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; Hampton, J.M.; Song, J.; Jayasekera, J.; Schechter, C.; et al. Analysis of Breast Cancer Mortality in the US—1975 to 2019. JAMA 2024, 331, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, N.; Downes, M.H.; Ibelli, T.; Amakiri, U.O.; Li, T.; Tebha, S.S.; Balija, T.M.; Schnur, J.B.; Montgomery, G.H.; Henderson, P.W. The Psychological Impacts of Post-Mastectomy Breast Reconstruction: A Systematic Review. Ann. Breast Surg. 2024, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.Q.; Tan, V.K.M.; Choo, H.M.C.; Ong, J.; Krishnapriya, R.; Khong, S.; Tan, M.; Sim, Y.R.; Tan, B.K.; Madhukumar, P.; et al. Factors Influencing Patient Decision-Making between Simple Mastectomy and Surgical Alternatives: Patient Decision-Making between Simple Mastectomy and Surgical Alternatives. BJS Open 2019, 3, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, P.; Huffman, K.N.; Williams, T.; Deol, A.; Zorra, I.; Adam, T.; Donaldson, R.; Qureshi, U.; Gowda, K.; Galiano, R.D.; et al. Rates of Breast Reconstruction Uptake and Attitudes toward Breast Cancer and Survivorship among South Asians: A Literature Review. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 129, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retrouvey, H.; Solaja, O.; Gagliardi, A.R.; Webster, F.; Zhong, T. Barriers of Access to Breast Reconstruction: A Systematic Review. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 143, 465e–476e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flitcroft, K.; Brennan, M.; Spillane, A. Making Decisions about Breast Reconstruction: A Systematic Review of Patient-Reported Factors Influencing Choice. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 2287–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.X.N.; Cardoso, M.J.; Cheung, K.L.; Parks, R.M. Immediate Breast Reconstruction Uptake in Older Women with Primary Breast Cancer: Systematic Review. Br. J. Surg. 2022, 109, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipe, M.D.; Siesling, S.; Vriens, M.R.; Van Diest, P.J.; Witkamp, A.J.; Mureau, M.A.M. Socioeconomic Status Significantly Contributes to the Likelihood of Immediate Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction in the Netherlands: A Nationwide Study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 47, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, B.A.; Samargandi, O.A.; Alghamdi, H.A.; Sayegh, A.A.; Hakeem, Y.J.; Merdad, L.; Merdad, A.A. The Desire to Utilize Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction in Saudi Arabian Women: Predictors and Barriers. Saudi Med. J. 2015, 36, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, P.D.; Nelson, J.A.; Fischer, J.P.; Wink, J.D.; Chang, B.; Fosnot, J.; Wu, L.C.; Serletti, J.M. Racial and Age Disparities Persist in Immediate Breast Reconstruction: An Updated Analysis of 48,564 Patients from the 2005 to 2011 American College of Surgeons National Surgery Quality Improvement Program Data Sets. Am. J. Surg. 2016, 212, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, L.C.; Greenfield, J.A.; Ainapurapu, S.S.; Skladman, R.; Skolnick, G.; Sundaramoorthi, D.; Sacks, J.M. The Insurance Landscape for Implant- and Autologous-Based Breast Reconstruction in the United States. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.-Glob. Open 2023, 11, e4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadakia, Y.; Liu, Y.; Farr, D.; Teotia, S.S.; Haddock, N.T. Translating Access to Outcomes: The Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Completion of Breast Reconstruction at a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-Designated Cancer Center. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2022, 75, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölmich, L.R.; Sayegh, F.; Salzberg, C.A. Immediate or Delayed Breast Reconstruction: The Aspects of Timing, a Narrative Review. Ann. Breast Surg. 2023, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoedler, S.; Kauke-Navarro, M.; Knoedler, L.; Friedrich, S.; Ayyala, H.S.; Haug, V.; Didzun, O.; Hundeshagen, G.; Bigdeli, A.; Kneser, U.; et al. The Significance of Timing in Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy: An ACS-NSQIP Analysis. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2024, 89, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronowitz, S.J. State of the Art and Science in Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 135, 755e–771e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco, N.; Catanuto, G.F.; Accardo, G.; Velotti, N.; Chiodini, P.; Cinquini, M.; Privitera, F.; Rispoli, C.; Nava, M.B. Implants versus Autologous Tissue Flaps for Breast Reconstruction Following Mastectomy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 2024, CD013821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offodile, A.C.; Wenger, J.; Guo, L. Relationship Between Comorbid Conditions and Utilization Patterns of Immediate Breast Reconstruction Subtypes Post-Mastectomy. Breast J. 2016, 22, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang-Azancot, L.; Abizanda, P.; Gijón, M.; Kenig, N.; Campello, M.; Juez, J.; Talaya, A.; Gómez-Bajo, G.; Montón, J.; Sánchez-Bayona, R. Age and Breast Reconstruction. Aesth Plast. Surg. 2023, 47, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, T.; Norman, K.; Burrett, V.; Scarlet, J.; Campbell, I.; Lawrenson, R. Key Factors in the Decision-Making Process for Mastectomy Alone or Breast Reconstruction: A Qualitative Analysis. Breast 2024, 73, 103600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergesketter, A.R.; Thomas, S.M.; Lane, W.O.; Shammas, R.L.; Greenup, R.A.; Hollenbeck, S.T. The Influence of Marital Status on Contemporary Patterns of Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2019, 72, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggal, C.S.; Metcalfe, D.; Sackeyfio, R.; Carlson, G.W.; Losken, A. Patient Motivations for Choosing Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2013, 70, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, N.S.; Penumadu, P.; Yadav, P.; Sethi, N.; Kohli, P.S.; Shankhdhar, V.; Jaiswal, D.; Parmar, V.; Hawaldar, R.W.; Badwe, R.A. Awareness and Acceptability of Breast Reconstruction Among Women With Breast Cancer: A Prospective Survey. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2021, 7, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mátrai, Z.; Kenessey, I.; Sávolt, Á.; Újhelyi, M.; Bartal, A.; Kásler, M. Evaluation of Patient Knowledge, Desire, And Psychosocial Background Regarding Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction in Hungary: A Questionnaire Study of 500 Cases. Med. Sci. Monit. 2014, 20, 2633–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somogyi, R.B.; Webb, A.; Baghdikian, N.; Stephenson, J.; Edward, K.; Morrison, W. Understanding the Factors That Influence Breast Reconstruction Decision Making in Australian Women. Breast 2015, 24, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Myckatyn, T.M.; Parikh, R.P.; Lee, C.; Politi, M.C. Challenges and Solutions for the Implementation of Shared Decision-Making in Breast Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.-Glob. Open 2020, 8, e2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, A.K.; Hawley, S.T.; Janz, N.K.; Mujahid, M.S.; Morrow, M.; Hamilton, A.S.; Graff, J.J.; Katz, S.J. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Use of Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction: Results From a Population- Based Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5325–5330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, M.; Li, Y.; Alderman, A.K.; Jagsi, R.; Hamilton, A.S.; Graff, J.J.; Hawley, S.T.; Katz, S.J. Access to Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy and Patient Perspectives on Reconstruction Decision Making. JAMA Surg. 2014, 149, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusic, A.L.; Matros, E.; Fine, N.; Buchel, E.; Gordillo, G.M.; Hamill, J.B.; Kim, H.M.; Qi, J.; Albornoz, C.; Klassen, A.F.; et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes 1 Year After Immediate Breast Reconstruction: Results of the Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2499–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albornoz, C.R.; Matros, E.; McCarthy, C.M.; Klassen, A.; Cano, S.J.; Alderman, A.K.; VanLaeken, N.; Lennox, P.; Macadam, S.A.; Disa, J.J.; et al. Implant Breast Reconstruction and Radiation: A Multicenter Analysis of Long-Term Health-Related Quality of Life and Satisfaction. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 21, 2159–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisell, A.; Lagergren, J.; Halle, M.; Boniface, J. Influence of Socioeconomic Status on Immediate Breast Reconstruction Rate, Patient Information and Involvement in Surgical Decision-making. BJS Open 2020, 4, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, R.; Jones, B.; Gardner, P.; Lawton, R. Quality Assessment with Diverse Studies (QuADS): An Appraisal Tool for Methodological and Reporting Quality in Systematic Reviews of Mixed- or Multi-Method Studies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaaly, H.A.; Mortada, H.; Trabulsi, N.H. Patient Perceptions and Determinants of Choice for Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy among Saudi Patients. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.-Glob. Open 2021, 9, e3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marouf, A.; Mortada, H.; Fakiha, M.G. Psychological, Sociodemographic, and Clinicopathological Predictors of Breast Cancer Patients’ Decision to Undergo Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy. Saudi Med. J. 2020, 41, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozawa, K.; Ichimura, M.; Oshima, A.; Tokunaga, E.; Masuda, N.; Kitano, A.; Fukuuchi, A.; Shinji, O. The Present State and Perception of Young Women with Breast Cancer towards Breast Reconstructive Surgery. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 20, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, R.; Szmigiel, K.; Rubin, A.; Borowiec, G.; Szelachowska, J.; Jagodziński, W.; Bębenek, M. Patient’s Education Before Mastectomy Influences the Rate of Reconstructive Surgery. J. Cancer Educ. 2017, 32, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Senger, J.-L.B.; Korus, L.; Rosychuk, R.J. Geographic Variation in Breast Reconstruction Surgery after Mastectomy for Females with Breast Cancer in Alberta, Canada. Can. J. Surg. 2024, 67, E172–E182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miseré, R.; Schop, S.; Heuts, E.; de Grzymala, A.P.; van der Hulst, R. Psychosocial Well-Being at Time of Diagnosis of Breast Cancer Affects the Decision Whether or Not to Undergo Breast Reconstruction. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 46, 1441–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaff, T.M.; AlTaleb, R.M.; Kattan, A.E.; Alsaif, H.K.; Murshid, R.E.; AlShaibani, T.J. STUDENTS’ CORNER KAP STUDY. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2019, 69, 1460–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, S.K.; Hare, R.M.; Kuang, R.J.; Smith, K.M.; Brown, B.J.; Hunter-Smith, D.J. Breast Reconstruction Post Mastectomy Patient Satisfaction and Decision Making. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2016, 76, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quemener, J.; Wallet, J.; Boulanger, L.; Hannebicque, K.; Chauvet, M.; Régis, C. Decision-making Determinants for Breast Reconstruction in Women over 65 Years Old. Breast J. 2019, 25, 1235–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siotos, C.; Lagiou, P.; Cheah, M.A.; Bello, R.J.; Orfanos, P.; Payne, R.M.; Broderick, K.P.; Aliu, O.; Habibi, M.; Cooney, C.M.; et al. Determinants of Receiving Immediate Breast Reconstruction: An Analysis of Patient Characteristics at a Tertiary Care Center in the US. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 34, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sue, G.R.; Lannin, D.R.; Au, A.F.; Narayan, D.; Chagpar, A.B. Factors Associated with Decision to Pursue Mastectomy and Breast Reconstruction for Treatment of Ductal Carcinoma in Situ of the Breast. Am. J. Surg. 2013, 206, 682–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, E.; Paraskeva, N.; Griffiths, C.; Hansen, E.; Clarke, A.; Baker, E.; Harcourt, D. The Nature and Importance of Women’s Goals for Immediate and Delayed Breast Reconstruction. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2021, 74, 2169–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manne, S.L.; Topham, N.; D’Agostino, T.A.; Myers Virtue, S.; Kirstein, L.; Brill, K.; Manning, C.; Grana, G.; Schwartz, M.D.; Ohman-Strickland, P. Acceptability and Pilot Efficacy Trial of a Web-Based Breast Reconstruction Decision Support Aid for Women Considering Mastectomy: Breast Reconstruction Decision Support Aid. Psycho-Oncol. 2016, 25, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momoh, A.O.; Griffith, K.A.; Hawley, S.T.; Morrow, M.; Ward, K.C.; Hamilton, A.S.; Shumway, D.; Katz, S.J.; Jagsi, R. Patterns and Correlates of Knowledge, Communication, and Receipt of Breast Reconstruction in a Modern Population-Based Cohort of Patients with Breast Cancer. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 144, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunta, S.; Laidsaar-Powell, R.; Huang, L.; Hatcher, N.; Dhillon, H.; Muscat, D.M.; Carroll, S.; McNeil, C.; Burke, L.; Howson, P.; et al. Considering the Type and Timing of Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy: Qualitative Insights into Women’s Decision-Making. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 54, 102024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danko, D.; Liu, Y.; Geng, F.; Gillespie, T.W. Influencers of Immediate Postmastectomy Reconstruction: A National Cancer Database Analysis. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2022, 42, NP297–NP311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flitcroft, K.; Brennan, M.; Costa, D.; Wong, A.; Snook, K.; Spillane, A. An Evaluation of Factors Affecting Preference for Immediate, Delayed or No Breast Reconstruction in Women with High-Risk Breast Cancer: Reasons for Reconstruction in Women with High-Risk Breast Cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2016, 25, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunta, R.E.; Hansson, E.; Andresen, C.; Athanasopoulos, E.; Benedetto, G.D.; Celebic, A.B.; Caulfield, R.; Costa, H.; Demirdöver, C.; Georgescu, A.; et al. ESPRAS Survey on Breast Reconstruction in Europe. Handchir. Mikrochir. Plast. Chir. 2021, 53, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.N.; Ubel, P.A.; Deal, A.M.; Blizard, L.B.; Sepucha, K.R.; Ollila, D.W.; Pignone, M.P. How Informed Is the Decision About Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy?: A Prospective, Cross-Sectional Study. Ann. Surg. 2016, 264, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, C.C.; Lennox, P.A.; Clugston, P.A.; Courtemanche, D.J. Breast Reconstruction in Older Women: Should Age Be an Exclusion Criterion? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006, 118, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeevan, R.; Browne, J.P.; Gulliver-Clarke, C.; Pereira, J.; Caddy, C.M.; van der Meulen, J.H.P.; Cromwell, D.A. Association between Age and Access to Immediate Breast Reconstruction in Women Undergoing Mastectomy for Breast Cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2017, 104, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavioso, C.; Pereira, C.; Cardoso, M.J. Oncoplastic Surgery and Breast Reconstruction in the Elderly: An Unsolved Conundrum. Ann. Breast Surg. 2023, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroyen, S.; Missotten, P.; Jerusalem, G.; Gilles, C.; Adam, S. Ageism and Caring Attitudes among Nurses in Oncology. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisell, A.; Lagergren, J.; Boniface, J. National Study of the Impact of Patient Information and Involvement in Decision-Making on Immediate Breast Reconstruction Rates. Br. J. Surg. 2016, 103, 1640–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.Y.; Hu, Z.I.; Mehrara, B.J.; Wilkins, E.G. Radiotherapy in the Setting of Breast Reconstruction: Types, Techniques, and Timing. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, e742–e753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Weeks, C.M.; In, H.; Dodgion, C.M.; Golshan, M.; Chun, Y.S.; Hassett, M.J.; Corso, K.A.; Gu, X.; Lipsitz, S.R.; et al. Impact of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy on Breast Reconstruction. Cancer 2011, 117, 2833–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubaud, M.S.; Carey, J.N.; Vartanian, E.; Patel, K.M. Breast Reconstruction in the High-Risk Population: Current Review of the Literature and Practice Guidelines. Gland. Surg. 2021, 10, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morena, N.; Ben-Zvi, L.; Hayman, V.; Hou, M.; Gorgy, A.; Nguyen, D.; Rentschler, C.A.; Meguerditchian, A.N. How Reliable Are Post-Mastectomy Breast Reconstruction Videos on YouTube? Surg. Oncol. Insight 2024, 1, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobke, M.K.; Yee, B.; Mackert, G.A.; Zhu, W.Y.; Blair, S.L. The Influence of Patient Exposure to Breast Reconstruction Approaches and Education on Patient Choices in Breast Cancer Treatment. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2019, 83, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, C.; Sharma, V.; Temple-Oberle, C. Delivering Breast Reconstruction Information to Patients: Women Report on Preferred Information Delivery Styles and Options. Plast. Surg. 2018, 26, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuyts, K.; Durston, V.; Morstyn, L.; Mills, S.; White, V. Information Needs in Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy: A Qualitative Analysis of Free-Text Responses from 2077 Women. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 205, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamore, K.; Vioulac, C.; Fasse, L.; Flahault, C.; Quintard, B.; Untas, A. Couples’ Experience of the Decision-Making Process in Breast Reconstruction After Breast Cancer: A Lexical Analysis of Their Discourse. Cancer Nurs. 2020, 43, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Glinski, M.; Holler, N.; Kümmel, S.; Wallner, C.; Wagner, J.M.; Sogorski, A.; Reinkemeier, F.; Reinisch, M.; Lehnhardt, M.; Behr, B. The Partner Perspective on Autologous and Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2023, 47, 1324–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, S.K.; Leal, I.M.; Nitturi, V.; Iwundu, C.N.; Maza, V.; Reyes, S.; Acquati, C.; Reitzel, L.R. Empowered Choices: African-American Women’s Breast Reconstruction Decisions. Am. J. Health Behav. 2021, 45, 352–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bochtsou, V.; Effraimidou, E.I.; Samakouri, M.; Plakias, S.; Arvaniti, A. Objective and Subjective Factors Influencing Breast Reconstruction Decision-Making After Breast Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111307

Bochtsou V, Effraimidou EI, Samakouri M, Plakias S, Arvaniti A. Objective and Subjective Factors Influencing Breast Reconstruction Decision-Making After Breast Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(11):1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111307

Chicago/Turabian StyleBochtsou, Valentini, Eleni I. Effraimidou, Maria Samakouri, Spyridon Plakias, and Aikaterini Arvaniti. 2025. "Objective and Subjective Factors Influencing Breast Reconstruction Decision-Making After Breast Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 11: 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111307

APA StyleBochtsou, V., Effraimidou, E. I., Samakouri, M., Plakias, S., & Arvaniti, A. (2025). Objective and Subjective Factors Influencing Breast Reconstruction Decision-Making After Breast Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(11), 1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111307