A Bibliometric Review of Person-Centered Care Research 2010–2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

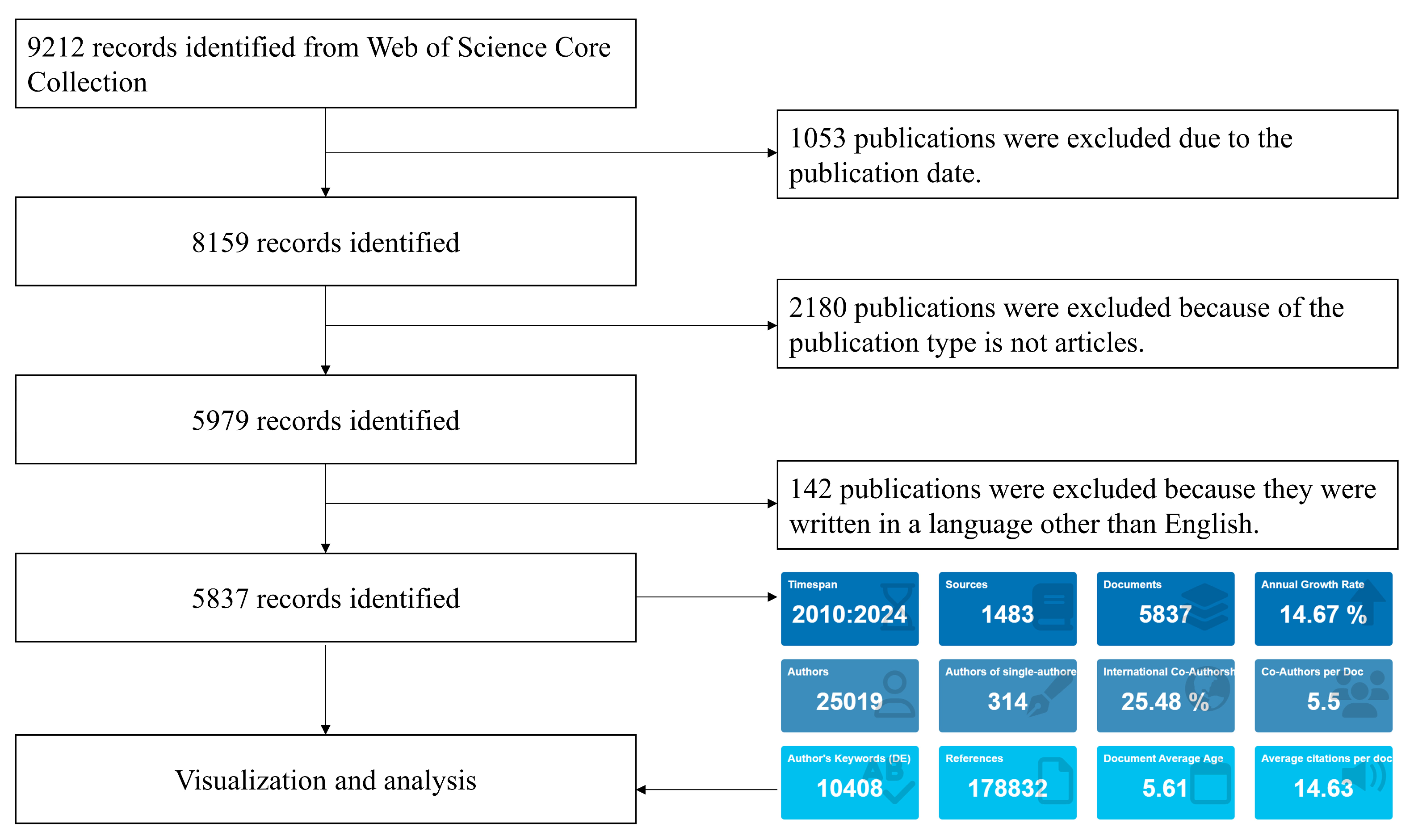

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

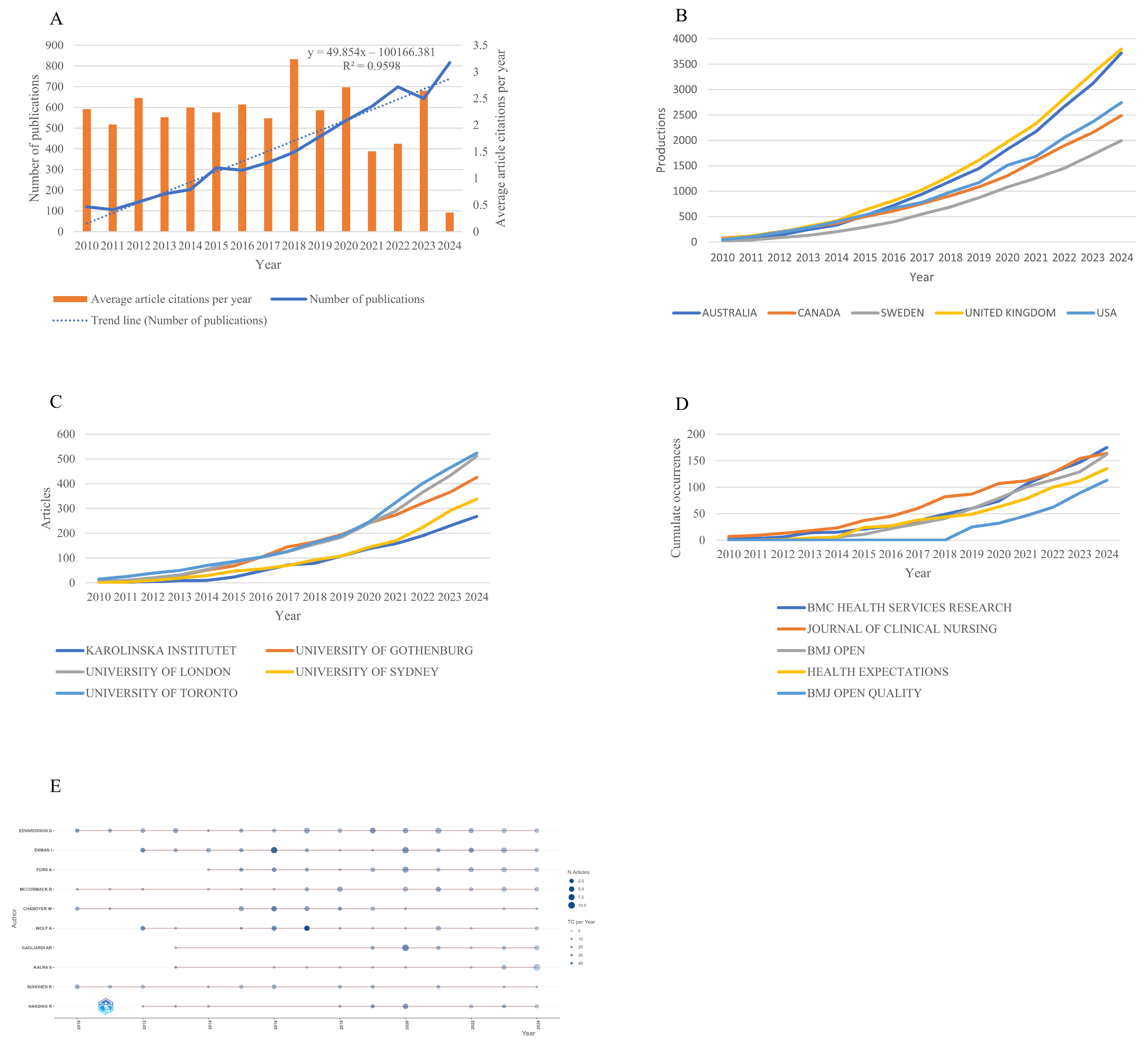

3.1. Research Trends

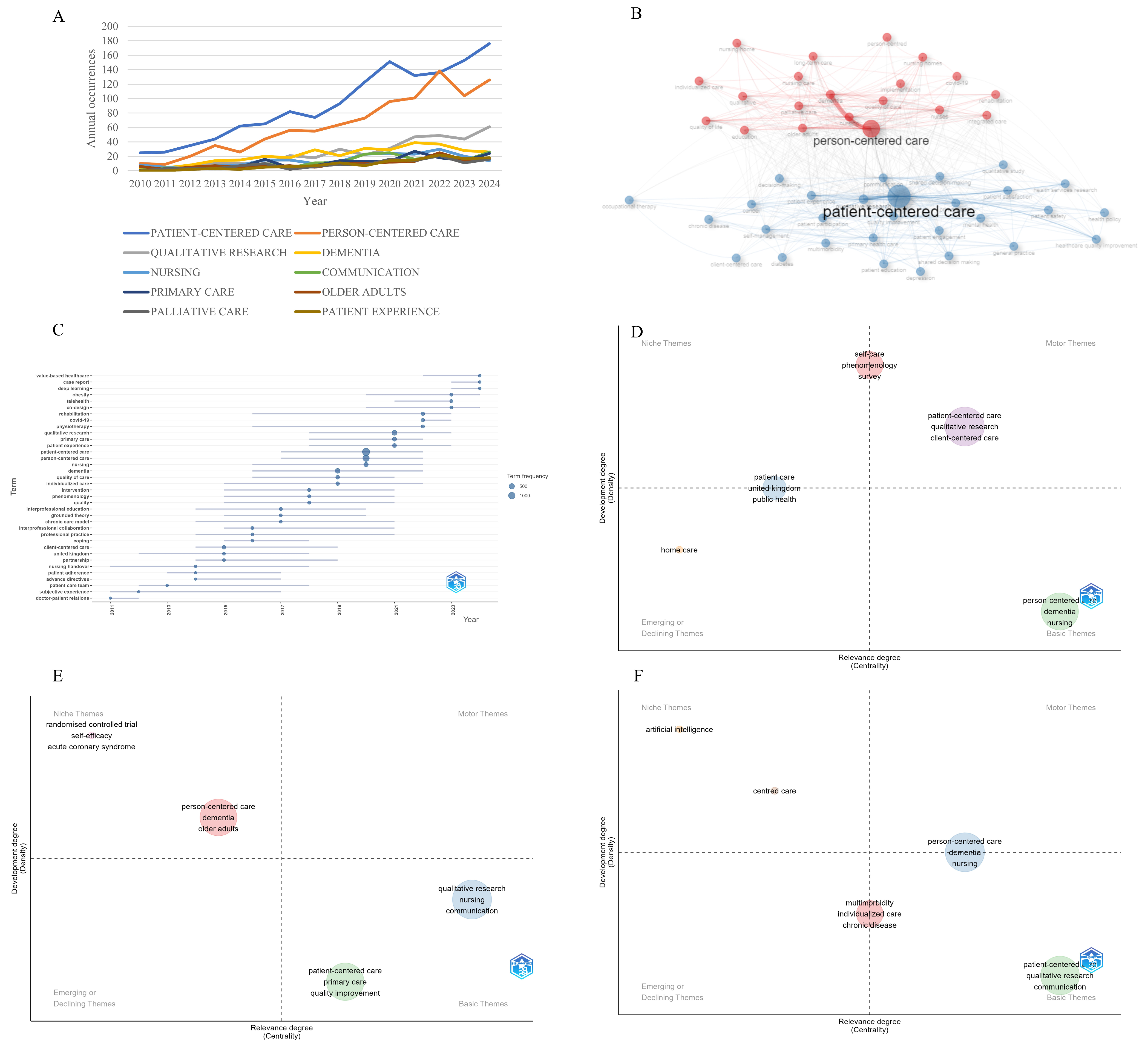

3.2. Hotspots Investigation

4. Discussion

5. Practical Implications

6. Limitation

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCC | Person-centered care |

| WOS | Web of Science |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Byrne, A.-L.; Baldwin, A.; Harvey, C. Whose centre is it anyway? Defining person-centred care in nursing: An integrative review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, J.H.; Holmström, I.K.; Kumlin, T.; Kaminsky, E.; Skoglund, K.; Höglander, J.; Sundler, A.J.; Condén, E.; Meranius, M.S. “Same same or different?” A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekman, I.; Ebrahimi, Z.; Contreras, P.O. Person-centred care: Looking back, looking forward. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2021, 20, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, R.B.; Wolka, E.; Nigatu, F.; Zewdie, A.; Erku, D.; Endalamaw, A.; Assefa, Y. People-centred primary health care: A scoping review. BMC Prim. Care 2023, 24, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, L.M. Patient-Centeredness Through Shared Decision-Making. In The Patient and Health Care System: Perspectives on High-Quality Care; Sreeramoju, P.V., Weber, S.G., Snyder, A.A., Kirk, L.M., Reed, W.G., Hardy-Decuir, B.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani, F.; Anbohi, S.Z.; Esmaeili, R.; Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Borhani, F. Person-centered Nursing to Improve Treatment Regimen Adherence in Patients with Myocardial Infarction. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2018, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlake, D.; Ekman, I.; Britten, N.; Lloyd, H. Terms of engagement for working with patients in a person-centred partnership: A secondary analysis of qualitative data. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 30, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pinho, L.G.; Lopes, M.J.; Correia, T.; Sampaio, F.; Arco, H.R.D.; Mendes, A.; Marques, M.D.C.; Fonseca, C. Patient-Centered Care for Patients with Depression or Anxiety Disorder: An Integrative Review. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, S.; Eliasson, B.; Andersson, E.; Johannsson, G.; Ringström, G.; Simrén, M.; Ung, E.J. Person-centred inpatient care—A quasi-experimental study in an internal medicine context. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 1678–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, K.; Brannefors, P.; Carlstrom, E. Adoption of the concept of person-centred care into discourse in Europe: A systematic literature review. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2021, 35, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweileh, W.M. Analysis and mapping the research landscape on patient-centred care in the context of chronic disease management. J. Evaluation Clin. Pract. 2024, 30, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.; Fitzpatrick, A.; Azim, F.T.; Ariza-Vega, P.; Bellwood, P.; Burns, J.; Burton, E.; Fleig, L.; Clemson, L.; Hoppmann, C.A.; et al. Defining and implementing patient-centered care: An umbrella review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano, F.; Alves, E.; João, A.; Oliveira, H.; Pinho, L.G.; Fonseca, C. A rapid literature review on the health-related outcomes of long-term person-centered care models in adults with chronic illness. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1213816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M.; Madevu-Matson, C.; Posner, J.E.; Zwick, H.; Sharer, M.; Powell, A.M. Systematic review: Development of a person-centered care framework within the context of HIV treatment settings in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2022, 27, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgers, J.S.; van der Weijden, T.; Bischoff, E.W.M.A. Challenges of Research on Person-Centered Care in General Practice: A Scoping Review. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 669491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, K.H.; Roslan, M.F.; Ishak, N.S.; Ilias, M.; Dani, R. Unearthing Hidden Research Opportunities Through Bibliometric Analysis: A Review. Asian J. Res. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2023, 5, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. People-Centred Health Care: A Policy Framework; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/206971/9789290613176_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- World Health Organization. Framework on Integrated, People-Centred Health Services; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_39-en.pdf?ua=1%26ua=1 (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Falagas, M.E.; Pitsouni, E.I.; Malietzis, G.A.; Pappas, G.; Kouranos, V.D.; Arencibia-Jorge, R.; Karageorgopoulos, D.E.; Reagan-Shaw, S.; Nihal, M.; Ahmad, N.; et al. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Singh, P.; Karmakar, M.; Leta, J.; Mayr, P. The journal coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 5113–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanitskaya, L.V.; Bogner, M.P. Culture Change in Older Adult Care Settings: A Bibliometric Review. Gerontologist 2024, 64, gnad128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojic, S.; Boehl, G.; Rubinelli, S.; Brach, M.; Jakob, R.; Kostanjsek, N.; Stoyanov, J.; Glisic, M. Two decades of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in health research: A bibliometric analysis. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2025, 20, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossiter, C.; Levett-Jones, T.; Pich, J. The impact of person-centred care on patient safety: An umbrella review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 109, 103658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, M.R. Person-Centered Approach to Transcultural Health Care. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2025, 36, 221–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Pacheco, J.; Ten Hoope-Bender, P. Person-centered Women’s Health and Maternity Care. In Person Centered Medicine; Mezzich, J.E., Appleyard, W.J., Glare, P., Snaedal, J., Wilson, C.R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 355–365. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, D.R.R.; Swift, A.; Allik, M.; McMahon, A.D.; Brown, D. Physical health of care-experienced young children in high-income countries: A scoping review. Lancet 2023, 402, S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yegros-Yegros, A.; van de Klippe, W.; Abad-Garcia, M.F.; Rafols, I. Exploring why global health needs are unmet by research efforts: The potential influences of geography, industry and publication incentives. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsagoor, H.M.S.; Al Fadhil, S.H.B.; Almushraaf, A.S.H.; Almansour, A.M.A.; Alqawban, S.M.H.; Al Atiq, A.Q.H.; Alghubari, F.M.M.; Alyami, M.M.H.; Algahes, M.M. Patient-Centered Care Models in Primary Healthcare: A Systematic Review of Implementation and Outcomes. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 2682–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitson, A.; Marshall, A.; Bassett, K.; Zeitz, K. What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starfield, B. Is Patient-Centered Care the Same as Person-Focused Care? Perm. J. 2011, 15, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chalmers, N.I.; Brow, A.; Boynes, S.; Monopoli, M.; Doherty, M.; Croom, O.; Engineer, L. Person-centered care model in dentistry. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, J.; Dave, S. Person-centred care and psychiatry: Some key perspectives. BJPsych. Int. 2020, 17, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.M.; Eckert, M.; Hutchinson, A.; Harmon, J.; Sharplin, G.; Shakib, S.; Caughey, G. Continuity of care for people with multimorbidity: The development of a model for a nurse-led care coordination service. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 37, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poksinska, B.; Wiger, M. From hospital-centered care to home-centered care of older people: Propositions for research and development. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2024, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Sun, L.; Liu, G.; Guan, B.; Li, C.; Luo, Y. Response of Global Health Towards the Challenges Presented by Population Aging. China CDC Wkly. 2023, 5, 884–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Salido, M.; Alhambra-Borrás, T.; Casanova, G.; Garcés-Ferrer, J. Value-Based Healthcare Delivery: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, Y. Defining and Implementing Value-Based Healthcare for Older People from a Geriatric and Gerontological Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, J.A.H. Patient-centered care coordination in population health case management. Nurs. Care Open Access J. 2018, 5, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossio-Gil, Y.; Omara, M.; Watson, C.; Casey, J.; Chakhunashvili, A.; Miguel, M.G.-S.; Kahlem, P.; Keuchkerian, S.; Kirchberger, V.; Luce-Garnier, V.; et al. The Roadmap for Implementing Value-Based Healthcare in European University Hospitals—Consensus Report and Recommendations. Value Health 2022, 25, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldosari, B. Information Technology and Value-Based Healthcare Systems: A Strategy and Framework. Cureus 2024, 16, e53760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bally, E.L.S.; van Grieken, A.; Ye, L.; Ferrando, M.; Fernández-Salido, M.; Dix, R.; Zanutto, O.; Gallucci, M.; Vasiljev, V.; Carroll, A.; et al. ‘Value-based methodology for person-centred, integrated care supported by Information and Communication Technologies’ (ValueCare) for older people in Europe: Study protocol for a pre-post controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Si, L. A Bibliometric Analysis of Digital Literacy Research from 1990 to 2022 and Research on Emerging Themes during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.M.; Chen, J.; Chunara, R.; Testa, P.A.; Nov, O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: Evidence from the field. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 1132–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granström, E.; Wannheden, C.; Brommels, M.; Hvitfeldt, H.; Nyström, M.E. Digital tools as promoters for person-centered care practices in chronic care? Healthcare professionals’ experiences from rheumatology care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed-Abdul, S.; Li, Y.-C. Empowering Patients and Transforming Healthcare in the Post-COVID-19 Era: The Role of Digital and Wearable Technologies. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Altalbe, A.; Naseer, F.; Awais, Q. Telehealth-Enabled In-Home Elbow Rehabilitation for Brachial Plexus Injuries Using Deep-Reinforcement-Learning-Assisted Telepresence Robots. Sensors 2024, 24, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, F.; Khan, M.; Addas, A. Healthcare Transformation Through Disruptive Technologies: The Role of Telepresence Robots. In Emerging Disruptive Technologies for Society 50 in Developing Countries; Arezki, S., Ouaissa, M., Ouaissa, M., Krichen, M., Nayyar, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Naseer, F.; Khan, M.N.; Nawaz, Z.; Awais, Q. Telepresence Robots and Controlling Techniques in Healthcare System. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 74, 6623–6639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, J.; Akhlaghpour, S.; Fatehi, F.; Gray, L.C. Data privacy concerns and use of telehealth in the aged care context: An integrative review and research agenda. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2022, 160, 104707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alodhialah, A.M.; Almutairi, A.A.; Almutairi, M. Telehealth Adoption Among Saudi Older Adults: A Qualitative Analysis of Utilization and Barriers. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansarian, M.; Baharlouei, Z. Applications and Challenges of Telemedicine: Privacy-Preservation as a Case Study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 26, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenoweth, L.; Stein-Parbury, J.; Lapkin, S.; Wang, A.; Liu, Z.; Williams, A. Effects of person-centered care at the organisational-level for people with dementia. A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L. The National Dementia Strategy: Transforming care. Nurs. Older People 2009, 21, 3. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia, 2017–2025. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513487 (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Mohr, W.; Rädke, A.; Afi, A.; Edvardsson, D.; Mühlichen, F.; Platen, M.; Roes, M.; Michalowsky, B.; Hoffmann, W. Key Intervention Categories to Provide Person-Centered Dementia Care: A Systematic Review of Person-Centered Interventions. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 84, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, A.W.; Surr, C.A.; Creese, B.; Garrod, L.; Chenoweth, L. The development and use of the assessment of dementia awareness and person-centred care training tool in long-term care. Dementia 2018, 18, 3059–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramm, J.M.; Nieboer, A.P. Validation of an instrument for the assessment of patient-centred care among patients with multimorbidity in the primary care setting: The 36-item patient-centred primary care instrument. BMC Fam. Pract. 2018, 19, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngangue, P.; Brown, J.B.; Forgues, C.; Ahmed, M.A.A.; Nguyen, T.N.; Sasseville, M.; Loignon, C.; Gallagher, F.; Stewart, M.; Fortin, M. Evaluating the implementation of interdisciplinary patient-centred care intervention for people with multimorbidity in primary care: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evén, G.; Spaak, J.; von Arbin, M.; Franzén-Dahlin, Å.; Stenfors, T. Health care professionals’ experiences and enactment of person-centered care at a multidisciplinary outpatient specialty clinic. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2019, 12, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.R.; Das, D.C.; Sunna, T.C.; Beyene, J.; Hossain, A. Global and regional prevalence of multimorbidity in the adult population in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 57, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborators GBDA. Global, regional, and national burden of diseases and injuries for adults 70 years and older: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study. BMJ 2022, 376, e068208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tong, L.-K.; Tam, H.-L.; Mao, A.-M. A Bibliometric Review of Person-Centered Care Research 2010–2024. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111267

Tong L-K, Tam H-L, Mao A-M. A Bibliometric Review of Person-Centered Care Research 2010–2024. Healthcare. 2025; 13(11):1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111267

Chicago/Turabian StyleTong, Lai-Kun, Hon-Lon Tam, and Ai-Mei Mao. 2025. "A Bibliometric Review of Person-Centered Care Research 2010–2024" Healthcare 13, no. 11: 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111267

APA StyleTong, L.-K., Tam, H.-L., & Mao, A.-M. (2025). A Bibliometric Review of Person-Centered Care Research 2010–2024. Healthcare, 13(11), 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111267