The Body Can Balance the Score: Using a Somatic Self-Care Intervention to Support Well-Being and Promote Healing

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Increased Need for Mental Health Interventions

1.2. Understanding Body-Based Approaches to Mental Health

1.3. Significance of Examining Somatic Interventions

2. Theoretical Bases for Interoceptive Awareness Based Interventions

2.1. Fight and Flight

2.2. The Stress Response

2.3. Interoception

3. Interoceptive Awareness Training

3.1. Applications and Measurement

- A 10 to 12 h online training program of interoceptive and emotional awareness, mindfulness, emotion recognition, and emotion regulation strategies found reduced emotion suppression and greater impulse control relative to placebo [61].

- A 4-session online interoceptive training intervention (Reconnecting to Internal Sensations and Experiences) increased interoceptive sensibility with the goal of reducing suicidality in veterans [62].

- An 8-week manualized program in Mindful Awareness in Body-oriented Therapy used interoception as an adjunct to buprenorphine for a small group of individuals with opioid use disorder, and results included satisfaction with the training and increased interoceptive awareness [63].

- A study of a 4-day training in Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT) for clinical therapy clients found significant improvements in resting heart rate, blood pressure, and cortisol, as well as several psychological measures [64]. EFT blends cognitive and exposure techniques with somatic stimulation of acupressure points on the face, arms, and head [64,65].

- Weng and colleagues are suggesting that interoceptive pathways can be manipulated through neuromodulation of the vagus nerve, slow breathing, and mindfulness-based interventions at neural, behavioral, and psychological levels to alter interoceptive signals to improve functioning and adaptive behavior [17].

- Auricular vagus nerve stimulation is being used as neuromodulation of the vagus nerve areas to alter emotional processing with interoceptive functioning in emotional disorders [66].

3.2. Training Specific to Wellness Programs

4. The Community Resiliency Model (CRM) ® as an Exemplar

4.1. Origin of the Model

4.2. Theoretical Underpinnings

- Nervous System Regulation: CRM highlights the role of the autonomic nervous system in shaping how individuals respond to stress and safety. Drawing from Polyvagal Theory, CRM emphasizes the vagus nerve’s role in regulating emotional and physiological states and supports returning to a “Resilient Zone” where optimal functioning occurs.

- Neuroplasticity: CRM is grounded in the principle that the brain and nervous system can reorganize through experience. Repeated use of CRM’s wellness skills supports the development of new neural pathways that enhance emotional regulation and resilience.

- Solution-Focused Psychotherapy: CRM reflects the strengths-based orientation of this short-term therapeutic model, focusing on clients’ internal resources and envisioning a preferred future. It operates on the belief that individuals possess the capacity for change and that small, attainable steps can lead to meaningful progress.

- Sensory Integration Theory: CRM recognizes the importance of effective processing of sensory input—such as touch, movement, and sound—for behavioral and emotional regulation. When sensory integration is disrupted, individuals may become over- or under-responsive to stimuli. CRM helps restore balance by supporting awareness of internal sensory experiences.

- Somatic Psychology: CRM incorporates bottom-up approaches to healing, prioritizing body awareness over cognitive processing. Individuals are guided to track sensations—especially those linked to well-being—which supports nervous system stabilization and promotes embodied resilience.

- Public Health and Social Justice Orientation: Designed as a scalable, community-accessible model, CRM can be used by both professionals and laypersons. It is grounded in equity and cultural humility, with a focus on reaching underserved, trauma-impacted populations and fostering collective resilience.

- Systems Thinking and Community Psychology: CRM acknowledges that trauma and healing occur within relational and societal contexts. It promotes a systems-based approach to recovery, emphasizing empowerment, mutual support, and sustainable community capacity-building.

4.3. CRM’s Cornerstone Concept

4.4. Comparison of the Resilient Zone to Related Concepts

4.5. CRM Training Compared to Mindfulness

- (1)

- The Resilient Zone concept provides a framework for understanding regulated and dysregulated states of mind.

- (2)

- (3)

- Common emotion-dysregulation responses to stress and trauma (behavioral, cognitive, emotional, relational, spiritual, and physical) are discussed in an interactive format, even virtually.

- (4)

- ACEs are touched on, along with post-traumatic growth and/or positive experiences of childhood [79].

- (5)

- Brain networks related to survival (brainstem), emotions (limbic), and cognition (cortical) areas are explained in simple terms and tied into the Resilient Zone and dysregulated (High and Low) states so that learners have a new and more compassionate understanding of their own personal experiences, as well as the behaviors of people around them.

4.6. When Interoceptive Awareness Is Activating: The CRM Teacher Response

5. The Community Resiliency Model: Evidence Thus Far

5.1. Practical Application and the Evolution of CRM

5.2. Empirical Evidence Summary

5.3. Anecdotal Evidence and a Definition of Resilience

5.4. Questions Remain for Interoceptive Awareness Measures

6. Emerging Science Related to Somatic Interventions

6.1. Intrapersonal Synchrony

6.2. Interpersonal Synchrony

7. Discussion

7.1. A Sensory Awareness Connects to Health

7.2. Clarifying the Difference Between CRM and Similar Interventions

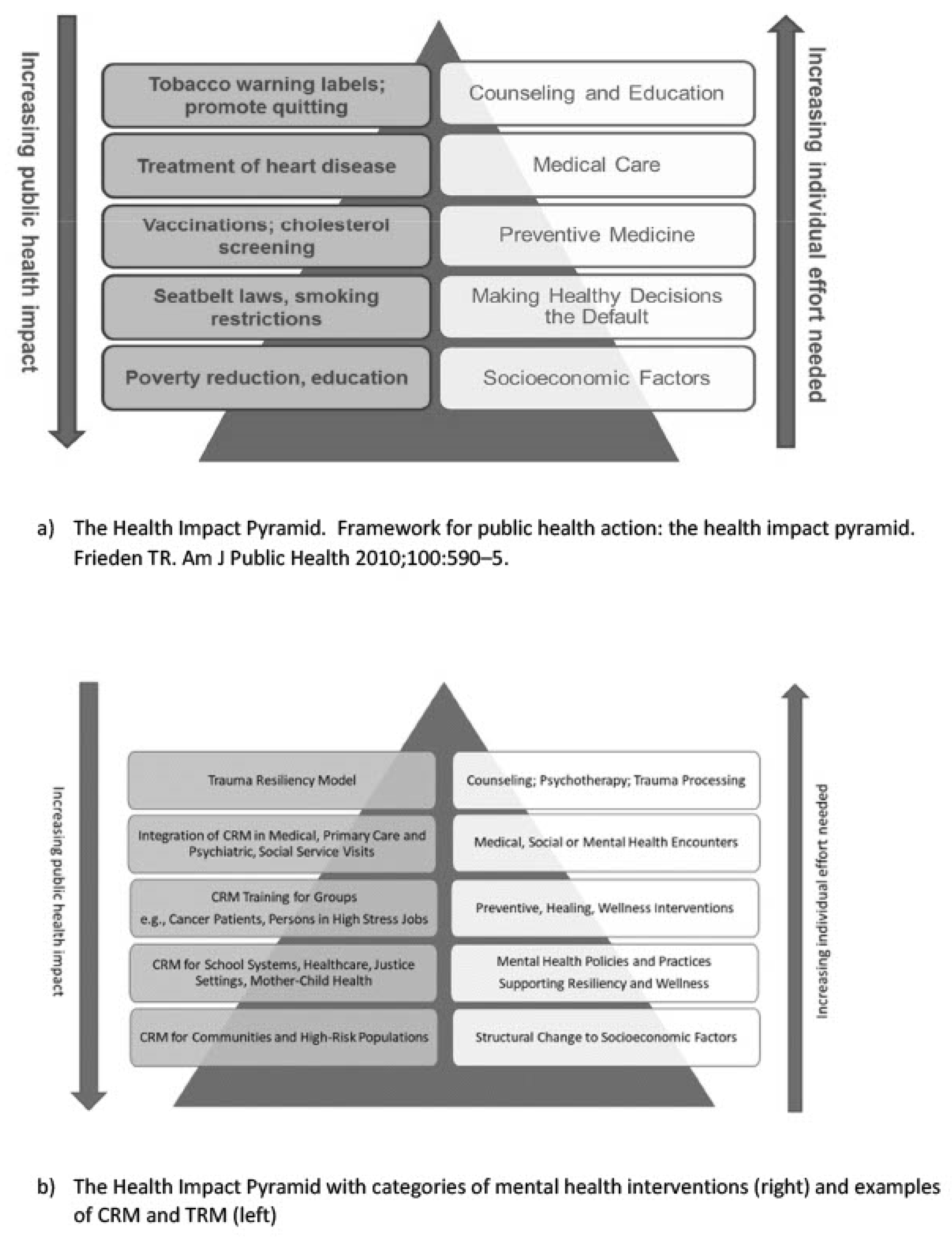

7.3. The Value of CRM from a Public Health Perspective

8. Future Research Directions

8.1. Brief Skills Training Knowledge Gaps

- (1)

- Biobehavioral measures of emotion regulation (cortisol levels, heart rate variability, electroencephalography, eye tracking);

- (2)

- Self-report or observation data on specific mental health problems (e.g., anxiety, depression) or behaviors (e.g., substance use, violence, incarceration);

- (3)

- Positive mental health parameters: well-being, emotion regulation, resiliency, self-care;

- (4)

- Pro-social thinking and behaviors such as teamwork, communication, empathy, and self- and other-compassion;

- (5)

- Perception of the self, other, and the environmental (SOE) system using technically supported biobehavioral measures;

- (6)

- Interpersonal synchronization of the SOE and its impact on work and learning, such as in groups and classrooms;

- (7)

- Community or public health outcomes;

- (8)

- Qualitative research on special groups, e.g., mother–infant interaction and family experience;

- (9)

- Brain imaging to detect the development of neural pathways and networks that reflect post-traumatic growth or resiliency pathways that counteract the harm of ACEs and trauma.

8.2. Hypotheses for Consideration in Brief Interoceptive Awareness Training Research

- Individuals who use somatic skill training will experience (a) greater self- and other compassion; emotion regulation; empathy; sense of well-being, and (b) reduced symptoms of stress, anxiety, depression, substance use, and other mental health issues.

- Individuals who suffer from chronic illness and who practice somatic skills will demonstrate a reduction in psychological distress and possibly markers of their illnesses.

- Members in group settings (e.g., in classrooms, day programs, community groups) who acquire somatic skill training will exhibit intra- and inter-brain synchrony as measured by heart rate variability, electroencephalography, and other biologic parameters.

- Communities that disseminate somatic skill trainings widely will have lower rates of the disorders and patterns identified as ACE outcomes, e.g., violence, substance use disorders, and mental health problems, e.g., suicidality, depression, loneliness, anxiety, PTSD, drug overdose.

- Communities that have suffered trauma (fires, shootings, natural disasters) that receive somatic skill interventions will have lower than expected subsequent rates of PTSD and other mental health fallout. Likewise, communities that are trained in somatic awareness prior to human-made or natural disasters will better withstand the impact of these events and will have a greater capacity to engage in mutual and community support within those disaster settings.

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study. Violence Prevention. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Barr, N.; Petering, R.; Onasch-Vera, L.; Thompson, N.; Polsky, R. MYPATH: A novel mindfulness and yoga-based peer leader interventino to prevent violence among youth experiencing homelessness. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 1952–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racine, N.; McArthur, B.A.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Zhu, J.; Madigan, S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torales, J.; O’Higgins, M.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Ventriglio, A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirsus and its impact on global mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Bremner, J.D.; Walker, J.D.; Whitfield, C.; Perry, B.D.; Dube, S.R.; Giles, W.H. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 256, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicher, M.H.; Samson, J.A. Annual Research Review: Enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, B.A. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-14-312774-1. [Google Scholar]

- Barratt, B. Research in Body Psychotherapy. In The Handbook of Body Psychotherapy and Somatic Psychology; North Atlantic Books: Berkley, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 834–845. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, F.; Fisher, J.; Nutt, D. Autonomic dysregulation and the Window of Tolerance model of the effects of complex emotional trauma. J. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 25, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, F.M.; Hull, A.M. Neglect of the complex: Why psychotherapy for post-traumatic clinical presentations is often ineffective. BJPsych Bull. 2015, 39, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, G.B.; Damasio, A. Interoception and the origin of feelings: A new synthesis. DioEssays 2021, 43, 2000261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottwald, C. Neurobiological Perspectives on Body Psychotherapy. In The Handbook of Body Psychotherapty and Somatic Psychology; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 126–147. [Google Scholar]

- Nummenmaa, L.; Glerean, E.; Hari, R.; Hietanen, J.K. Bodily maps of emotions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volynets, S.; Glerean, E.; Hietanen, J.K.; Hari, R.; Nummenmaa, L. Bodily maps of emotions are culturally universal. Emotion 2020, 20, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damasio, A.R. The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness, 1st ed.; Harcourt: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, H.Y.; Feldman, J.L.; Leggio, L.; Napadow, V.; Park, J.; Price, C.J. Interventions and manipulations of Interoception. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, H. Consciousness, Awareness, Mindfulness. In The Handbook of Body Psychotherapy and Somatic Psychology; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 402–410. [Google Scholar]

- Gendlin, E. “Felt Sense” as a Ground for Body Psychotherapies. In The Handbook of Body Psychotherapy and Somatic Psychology; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, A.D. How do you feel—Now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A.D. How do you feel? Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogolla, N. The insular cortex. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R580–R586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koban, L.; Gianaros, P.J.; Kober, H.; Wager, T.D. The self in context: Brain systems linking mental and physical health. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 22, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, P.A. Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma: The Innate Capacity to Transform Overwhelming Experiences; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-1-55643-233-0. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, P.A. In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-55643-943-8. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, P.; Levine, P.A.; Crane-Godreau, M.A. Somatic experienceing: Using interoception and proprioception as core elements of trauma therapy. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, L.; LaPierre, A. Healing Developmental Trauma: How Early Trauma Affects Self-Regulation, Self-Image, and the Capacity for Relationship; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-58394-489-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, P.; Minton, K.; Pain, C. Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy, 1st ed.; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-393-70457-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, P. Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment, 1st ed.; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, P.; Pain, C.; Fisher, J. A Sensorimotor Approach to the Treatment of Trauma and Dissociation. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2006, 29, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, B. The Body Remembers; W.W. Norton & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-393-70327-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild, B. 8 Keys to Safe Trauma Recovery: Take-Charge Strategies to Empower Your Healing, 1st ed.; W.W. Norton & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-393-70605-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild, B. The Body Remembers; W.W. Norton & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 2, ISBN 978-0-393-71279-7. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Karas, E. Building Resilience to Trauma: The Trauma and Community Resiliency Models; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-415-50063-0. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Karas, E. Building Resilience to Trauma: The Trauma and Community Resiliency Models, 2nd ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, K.; Boon, S.; van der Hart, O. Treating Trauma-Related Dissociation: A Practical, Integrative Approach; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-393-71263-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhfuß, M.; Maldei, T.; Hetmanek, A.; Baumann, N. Somatic experiencing—Effectiveness and key factors of a body-oriented trauma therapy: A scoping literature review. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1929023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farb, N.; Daubenmier, J.; Price, C.J.; Gard, T.; Kerr, C.; Dunn, B.D.; Klein, A.C.; Paulus, M.P.; Mehling, W.E. Interoception, contemplative practice, and health. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, W.B. Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage: An Account of Recent Researches into the Function of Emotional Exciteent; D. Appleton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1915. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.E. Social Support. In Foundations of Health Psychology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.E.; Gonzaga, G.C.; Klein, L.C.; Hu, P.; Greendale, G.A.; Seeman, T.E. Relation of Oxytocin to Psychological Stress Responses and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Axis Activity in Older Women. Psychosom. Med. 2006, 68, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korte, S.M.; Koolhaas, J.M.; Wingfield, J.C.; McEwen, B.S. The Darwinian concept of stress: Benefits of allostasis and costs of allostatic load and the trade-offs in health and disease. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005, 29, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Hart, O.; Nijenhuis, E.R.S.; Steele, K. The Haunted Self: Structural Dissociation and Treatment of Chronic Traumatization; W.W. Norton & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy, L.D.; Rossignoli, M.T.; Delfino-Pereira, P.; Garcia-Cairasco, N.; De Lima Umeoka, E.H. A Comprehensive Overview on Stress Neurobiology: Basic Concepts and Clinical Implications. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, S.A.; Wagner, A.D. Acute stress and episodic memory retrieval: Neurobiological mechanisms and behavioral consequences: Acute stress and episodic memory retrieval. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2016, 1369, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S.; Gianaros, P.J. Stress- and Allostasis-Induced Brain Plasticity. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011, 62, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabbe, L.; Duva, I.M.; Nicholson, W.C. The Community Resiliency Model, an interoceptive awareness tool to support population mental wellness. Camb. Prisms Glob. Ment. Health 2023, 10, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abele, A.E.; Ellemers, N.; Fiske, S.T.; Koch, A.; Yzerbyt, V. Navigating the social world: Toward an integrated framework for evaluating self, individuals, and groups. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 128, 290–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.G.; Schloesser, D.; Arensdorf, A.M.; Simmons, J.M.; Cui, C.; Valentino, R.; Gnadt, J.W.; Nielsen, L.; Hillaire-Clarke, C.S.; Spruance, V.; et al. The Emerging Science of Interoception: Sensing, Integrating, Interpreting, and Regulating Signals within the Self. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalsa, S.S.; Adolphs, R.; Cameron, O.G.; Critchley, H.D.; Davenport, P.W.; Feinstein, J.S.; Feusner, J.D.; Garfinkel, S.N.; Lane, R.D.; Mehling, W.E.; et al. Interoception and Mental Health: A Roadmap. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2018, 3, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalsa, S.S.; Feinstein, J.S.; Simmons, W.K.; Paulus, M.P. Taking Aim at Interoception’s Role in Mental Health. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2018, 3, 496–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critchley, H.D.; Garfinkel, S.N. Interoception and emotion. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 17, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suksasilp, C.; Garfinkel, S.N. Towards a comprehensive assessment of interoception in a multi-dimensional framework. Biol. Psychol. 2022, 168, 108262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelen, T.; Solcà, M.; Tallon-Baudry, C. Interoceptive rhythms in the brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 1670–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, L.Q.; Nomi, J.S.; Hébert-Seropian, B.; Ghaziri, J.; Boucher, O. Structure and Function of the Human Insula. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2017, 34, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulus, M.P.; Stein, M.B. Interoception in anxiety and depression. Brain Struct. Funct. 2010, 214, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wapner, J. The Paradox of Listening to Our Bodies Interoception-The Inner Sense Linking Our Bodies and Minds—Can Confuse s Much as It Can Reveal. The New Yorker, 6 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mehling, W.E.; Price, C.; Daubenmier, J.J.; Acree, M.; Bartmess, E.; Stewart, A. Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness. 2016. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft45826-000 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Mahler, K.; Hample, K.; Ensor, C.; Ludwig, M.; Palanzo-Sholly, L.; Stang, A.; Trevisan, D.; Hilton, C. An Interoception- Based Intervention for Improving Emotional Regulation in Children in a Special Education Classroom: Feasibility Study. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2024, 38, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, K.; Hample, K.; Jones, C.; Sensenig, J.; Thomasco, P.; Hilton, C. Impact of an Interoception-Based Program on Emotion Regulation in Autistic Children. Occup. Ther. Int. 2022, 2022, 9328967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Persich, M.R.; Chuning, A.E.; Cloonan, S.; Woods-Lubert, R.; Skalamera, J.; Berryhill, S.M.; Weihs, K.L.; Lane, R.D.; Allen, J.J.B.; et al. Improvements in mindfulness, interoceptive and emotional awareness, emotion regulation, and interpersonal emotion management following completion of an online emotional skills training program. Emotion 2024, 24, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.R.; Forrest, L.N.; Perkins, N.M.; Kinkel-Ram, S.; Bernstein, M.J.; Witte, T.K. Reconnecting to Internal Sensation and Experiences: A Pilot Feasibility Study of an Online Intervention to Improve Interoception and Reduce Suicidal Ideation. Behav. Ther. 2021, 52, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, C.J.; Merrill, J.O.; McCarty, R.L.; Pike, K.C.; Tsui, J.I. A pilot study of mindful body awareness training as an adjunct to office-based medication treatment of opioid use disorder. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2020, 108, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, D.; Groesbeck, G.; Stapleton, P.; Sims, R.; Blickheuser, K.; Church, D. Clinical EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) Improves Multiple Physiological Markers of Health. J. Evid.-Based Integr. Med. 2019, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Church, D.; Stapleton, P.; Mollon, P.; Feinstein, D.; Boath, E.; Mackay, D.; Sims, R. Guidelines for the Treatment of PTSD Using Clinical EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques). Healthcare 2018, 6, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranberri Ruiz, A. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation to Improve Emotional State. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittelmark, M.B.; Bauer, G.F. The Meanings of Salutogenesis. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis; Mittelmark, M.B., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Bauer, G.F., Pelikan, J.M., Lindström, B., Espnes, G.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 7–13. ISBN 978-3-319-04599-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, D.; Carleton, J. The role of the autonomic nervous system. In The Handbook of Psychotherapy and Somatic Psychology; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 615–632. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J. Mindfulness, Interoception, and the Body: A Contemporary Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.M.G. (Ed.) The Mindful Way Through Depression: Freeing Yourself from Chronic Unhappiness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-59385-128-6. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M. DBT Skills Training Manual, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Grabbe, L.; Nguy, S.T.; Higgins, M.K. Spirituality Development for Homeless Youth: A Mindfulness Meditation Feasibility Pilot. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2012, 21, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duva, I.M.; Murphy, J.; Grabbe, L. A Nurse-Led, Well-Being Promotion Using the Community Resiliency Model, Atlanta, 2020–2021. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, S272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbarger, J.; Wilbarger, P. Approach to Treating Sensory Defensiveness and Clinical Application of the Sensory Diet. In Sensory Integration: Theory and Practice; F.A. Davis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz-Krohn, W. Sensory Diet. In Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders; Springer Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, D. The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Briere, J.N.; Scott, C. Principles of Trauma Therapy, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life; Hachette Book Groupalance: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bethell, C.; Jones, J.; Gombojav, N.; Linkenbach, J.; Sege, R. Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Mental and Relational Health in a Statewide Sample: Associations Across Adverse Childhood Experiences Levels. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, e193007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Doctor, R.M.; Selvam, R. Somatic therapy treatment effects with tsunami survivors. Traumatology 2008, 14, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, M.L. Somatic Experiencing treatment with tsunami survivors in Thailand: Broadening the scope of early intervention. Traumatology 2007, 13, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, M.L.; Vanslyke, J.; Allen, M. Somatic experiencing treatment with social service workers following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Soc. Work 2009, 54, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, L.; Miller-Karas, E. A case for using biologically-based mental health intervention in post-earthquake china: Evaluation of training in the trauma resiliency model. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Health 2009, 11, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Forthal, S.; Sadowska, K.; Pike, K.M.; Balachander, M.; Jacobsson, K.; Hermosilla, S. Mental Health First Aid: A Systematic Review of Trainee Behavior and Recipient Mental Health Outcomes. Psychiatr. Serv. 2022, 73, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Feinn, R. Using Effect Size-or Why the P Value Is Not Enough. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2012, 4, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabbe, L.; Higgins, M.K.; Baird, M.; Craven, P.A.; San Fratello, S. The Community Resiliency Model® to promote nurse well-being. Nurs. Outlook 2020, 68, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duva, I.M.; Higgins, M.K.; Baird, M.; Lawson, D.; Murphy, J.R.; Grabbe, L. Practical resiliency training for healthcare workers during COVID-19: Results from a randomised controlled trial testing the Community Resiliency Model for well-being support. BMJ Open Qual. 2022, 11, e002011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, E.; Keita, M.; Koomson, C.; Tintle, N.; Adlam, K.; Farah, E.; Koenig, M.D. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of a Multimodal Wellness Intervention for Perinatal Mental Health. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, K.; Baek, K.; Ngo, M.; Kelley, V.; Karas, E.; Citron, S.; Montgomery, S. Exploring the Usability of a Community Resiliency Model Approach in a High Need/Low Resourced Traumatized Community. Community Ment. Health J. 2022, 58, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabbe, L.; Higgins, M.K.; Baird, M.; Pfeiffer, K.M. Impact of a Resiliency Training to Support the Mental Well-being of Front-line Workers: Brief Report of a Quasi-experimental Study of the Community Resiliency Model. Med. Care 2021, 59, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, C.; Jeter, L.; Duva, I.; Giordano, N.; Eldridge, R. Resilience Training in the Emergency Department. J. Nurse Pract. 2023, 19, 104760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habimana, S.; Biracyaza, E.; Habumugisha, E.; Museka, E.; Mutabaruka, J.; Montgomery, S.B. Role of Community Resiliency Model Skills Trainings in Trauma Healing Among 1994 Tutsi Genocide Survivors in Rwanda. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabbe, L.; Higgins, M.; Jordan, D.; Noxsel, L.; Gibson, B.; Murphy, J. The Community Resiliency Model®: A Pilot of an Interoception Intervention to Increase the Emotional Self-Regulation of Women in Addiction Treatment. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobe, M.; Walters, H.; Ulmer, S.; Clarke, J.; Mullen, A.; Carleson, N. Wellness within: Promoting healing-centered tools for pregnancy, birth and beyond. In Proceedings of the Implementing a Maternal Health and PRegnancy Outcomes Vision for Everyone (IMPROVE), Bethesda, MD, USA, 15–16 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aréchiga, A.; Freeman, K.; Tan, A.; Lou, J.; Lister, Z.; Buckles, B.; Montgomery, S. Building resilience and improving wellbeing in Sierra Leone using the community resiliency model post Ebola. Int. J. Ment. Health 2023, 53, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim-Célestin, M.; Rockwood, N.J.; Clarke, C.; Montgomery, S.B. Evaluating the Full Plate Living lifestyle intervention in low-income monolingual Latinas with and without food insecurity. Womens Health 2022, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, E.Q. A relational ecology for crisis prevention among unhoused indigenous peoples in Albuquerque. Psychother. Integr. 2023, 33, 384–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, D.I.; Phan, R.; Pueschel, R.; Truong, S.; Aréchiga, A. The Community Resiliency Model to enhance resilience among newly graduated nurses. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 55, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, J.R.; Morson, D.M.; Montgomery, A.P.; Ruffin, A.; Polancich, S.; Beam, T.; Blackburn, C.; Carter, J.-L.; Dick, T.; Westbrook, J.; et al. Navigating Challenges: The Impact of Community Resiliency Model Training on Nurse Leaders. Nurse Lead. 2024, 22, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, N.A.; Duva, I.; Swan, B.A.; Johnson, T.M.; Cimiotti, J.P.; Lamis, D.A.; Hillman, J.; Gowgiel, J.; Giordano, K.; Rider, N.; et al. Effects of a Workplace Well-being Program on Professional Quality of Life Among Healthcare Personnel. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.M. Community Resiliency Model Training: One Nurse’s Experience. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2024, 45, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabbe, L.; Duva, I.; Jackson, D.; Johnson, R.; Schwartz, D. The impact of the Community Resiliency Model (CRM) on the mental well-being of youth at risk for violence: A study protocol. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2023, 46, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Karas, E.; Karas-Waterson, J. Addiction, Dependence and Substance Use Disorder. In Building Resilience to Trauma: The trauma and Community Resiliency Models, 2nd ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2023; pp. 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Karas, E. Building Resiliency to Trauma Providing Support to Ukraine During War with Telemental Health Using hte Community Resiliency Model to Reduce Toxic Stress. Psychology Today. 23 April 2022. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/building-resiliency-trauma/202204/providing-support-ukraine-during-war-telemental-health (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Lykins, E.; Button, D.; Krietemeyer, J.; Sauer, S.; Walsh, E.; Duggan, D.; Williams, J.M.G. Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment 2008, 15, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Hopkins, J.; Krietemeyer, J.; Toney, L. Using Self-Report Assessment Methods to Explore Facets of Mindfulness. Assessment 2006, 13, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlmeijer, E.; ten Klooster, P.M.; Fledderus, M.; Veehof, M.; Baer, R. Psychometric properities of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in depressed adults and developmet of a short form. Assessment 2011, 18, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balconi, M.; Allegretta, R.A.; Angioletti, L. Autonomic synchrony induced by hyperscanning interoception during interpersonal synchronization tasks. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1200750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berntson, G.G.; Khalsa, S.S. Neural Circuits of Interoception. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berntson, G.G.; Gianaros, P.J.; Tsakiris, M. Interoception and the autonomic nervous system: Bottom-up meets top-down. In The Interoceptive Mind: From Homeostasis to Awareness; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gansel, K Neural synchrony in cortical networks: Mechanisms and implications for neural information processing and coding. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 900715. [CrossRef]

- Beppi, C.; Violante, I.R.; Hampshire, A.; Grossman, N.; Sandrone, S. Patterns of Focal- and Large-Scale Synchronization in Cognitive Control and Inhibition: A Review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar-Szakacs, I.; Uddin, L.Q. Anterior insula as a gatekeeper of executive control. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 139, 104736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozakevich Arbel, E.; Shamay-Tsoory, S.G.; Hertz, U. Adaptive Empathy: Empathic Response Selection as a Dynamic, Feedback-Based Learning Process. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 706474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzoratti, A.; Evans, T.M. Measurement of interpersonal physiological synchrony in dyads: A review of timing parameters used in the literature. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 22, 1215–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinero, D.A.; Dikker, S.; Van Bavel, J.J. Inter-brain synchrony in teams predicts collective performance. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2021, 16, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamay-Tsoory, S.G.; Saporta, N.; Marton-Alper, I.Z.; Gvirts, H.Z. Herding Brains: A Core Neural Mechanism for Social Alignment. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019, 23, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Lou, W.; Huang, X.; Ye, Q.; Tong, R.K.-Y.; Cui, F. Suffer together, bond together: Brain-to-brain synchronization and mutual affective empathy when sharing painful experiences. NeuroImage 2021, 238, 118249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrocchi, N.; Cheli, S. The social brain and heart rate variability: Implications for psychotherapy. Psychol. Psychother. 2019, 92, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberz, J.; Shamay-Tsoory, S.G.; Saporta, N.; Kanterman, A.; Gorni, J.; Esser, T.; Kuskova, E.; Schultz, J.; Hurlemann, R.; Scheele, D. Behavioral and Neural Dissociation of Social Anxiety and Loneliness. J. Neurosci. 2022, 42, 2570–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia, A.L.; Froese, T. What binds us? Inter-brain neural synchronization and its implications for theories of human consciousness. Neurosci. Conscious. 2020, 2020, niaa010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeszumski, A.; Eustergerling, S.; Lang, A.; Menrath, D.; Gerstenberger, M.; Schuberth, S.; Schreiber, F.; Rendon, Z.Z.; König, P. Hyperscanning: A Valid Method to Study Neural Inter-brain Underpinnings of Social Interaction. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotter, L.D.; Kohl, S.H.; Gerloff, C.; Bell, L.; Niephaus, A.; Kruppa, J.A.; Dukart, J.; Schulte-Rüther, M.; Reindl, V.; Konrad, K. Revealing the neurobiology underlying interpersonal neural synchronization with multimodal data fusion. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 146, 105042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, G.; Sestieri, C.; Corbetta, M. The evolution of the tempoparietal junction and posterior superior temporal sulcus. Cortex 2019, 118, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, C.M. The Transdiagnostic Relevance of Self-Other Distinction to Psychiatry Spans Emotional, Cognitive and Motor Domains. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 797952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, L.; Salomonski, C.; Peleg, I.; Hayut, O.; Zagoory-Sharon, O.; Feldman, R. Social interactions between attachment partners increase inter-brain plasticity. SSRN Prepr. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalde, S.F.; Rigby, A.; Keller, P.E.; Novembre, G. A framework for joint music making: Behavioral findings, neural processes, and computational models. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 167, 105816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, D.; Davidesco, I.; Wan, L.; Chaloner, K.; Rowland, J.; Ding, M.; Poeppel, D.; Dikker, S. Brain-to-Brain Synchrony and Learning Outcomes Vary by Student–Teacher Dynamics: Evidence from a Real-world Classroom Electroencephalography Study. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2019, 31, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidesco, I.; Laurent, E.; Valk, H.; West, T.; Milne, C.; Poeppel, D.; Dikker, S. The Temporal Dynamics of Brain-to-Brain Synchrony Between Students and Teachers Predict Learning Outcomes. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 34, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakewell, S. How to Live, or, A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer; First Softcover Printing; Other Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Frieden, T.R. A Framework for Public Health Action: The Health Impact Pyramid. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, J.M.; Leider, J.P.; Resnick, B.; Bishai, D. Aligning US Spending Priorities Using the Health Impact Pyramid Lens. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, S181–S185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkin, A.M.; Rao, S.; Venugopal, J.; Kithulegoda, N.; Wegier, P.; Ritchie, S.D.; VanderBurgh, D.; Martiniuk, A.; Salamanca-Buentello, F.; Upshur, R. Conceptual framework for task shifting and task sharing: An international Delphi study. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, A.; Verhey, R.; Mosweu, I.; Boadu, J.; Chibanda, D.; Chitiyo, C.; Wagenaar, B.; Senra, H.; Chiriseri, E.; Mboweni, S.; et al. Economic threshold analysis of delivering a task-sharing treatment for common mental disorders at scale: The Friendship Bench, Zimbabwe. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2022, 25, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A.R. Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow, and the Feeling Brain, 1st ed.; Harcourt: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

| Skill | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Tracking: Monitoring one’s own physical sensations, both external and internal. | While walking, I focus on the strength in my legs; in difficult situations, I can “sense-in” to my body, noticing sensations in my chest, abdomen, or limbs. |

| 2. | Resourcing: Identifying resources, including internal (e.g., a personal strength or characteristic), external (e.g., faith, family, friends, pets), or imagined (e.g., a superhero, a literary character) helps individuals return to a state of balance during or after a stressful experience. | I recall a beach scene as a child, remembering the salty smell, the crash of surf, the heat of the sun, the sand sticking to my arms. When I think about the scene, I take a deep breath and notice stability in my chest. |

| 3. | Grounding: Paying attention to the body or part of the body making contact with a surface of support, which can be calming and help people to be present in the moment. | I bring attention to the sensation of pavement under my feet on my way to the parking deck. I notice the texture and temperature of my steering wheel while driving, my clothing, my own skin, settling me. |

| 4. | Gesturing: Gestures can emerge spontaneously, usually below conscious awareness, like a self-soothing touch. Gesturing involves intentionally making a movement or gesture associated with well-being, e.g., joy, happiness, courage. | When I am stressed, I put my hand over my chest or rub my wrist or knuckles. I notice I take a deeper breath at that moment and feel lighter. |

| 5. | Help Now!: Inducing a resiliency pause, ten sample strategies are taught that can reset the nervous system when a person is in a hyper- or hypo-aroused state to help them return to a state of balance. | When I feel overwhelmed, I name the colors or objects in the room to myself, noticing a calming as I proceed. I can push my arms against a wall, engaging the muscles. Sensations of energy move from my chest out to my arms, I am less distressed. |

| 6. | Shift and Stay: Discerning whether we are in a balanced state or not while Tracking, intentionally shifting or staying with neutral or pleasant sensations for about 10–15 s to widen the Resilient Zone. | I was in a bad mood and thought of my beach resource, remembering the sensory details of that experience. I stayed thinking about it and noticing sensations for about 15 s and noticed relief and balance. |

| China Sichuan Province Earthquake | 2008–2010 |

| Haiti Earthquake | 2010–present |

| Philippines Typhoon Haiyan | 2014–2020 |

| Rwanda (post-genocide trauma) | 2009–present |

| Nepal Katmandu Earthquake | 2015–2016 |

| Northern Uganda War- Lord’s Resistance Army | 2016–present |

| Mass Shootings: San Bernardino, CA, Pulse Attack, FL, Dayton, OH, Thousand Oaks, CA, Nashville, TN. | 2015–present |

| Butte County, CA (Camp Fire) | 2019–2020 |

| Ukrainian Humanitarian Resiliency Project | 2022–present |

| Maui, Hawaii (in process) | 2023–2024 |

| Belfast, Northern Ireland | 2016–present |

| Turkey (Syrian Refugees) | 2016–1017 |

| Angola, Post Civil War Project, Resiliency Project | 2023–present |

| Israel Humanitarian Project | 2023–present |

| Palestine Humanitarian Project | 2023–present |

| The Rwanda Resilience and Grounding Organization | https://www.rrgo.org/ (accessed on 10 May 2025). |

| Social, Emotional and Ethical Learning program of Emory University | https://compassion.emory.edu/see-learning/ (accessed on 10 May 2025). |

| Cognitively Based Compassion Training at the Emory University Center for Contemplative Science | https://compassion.emory.edu/cbct-compassion-training/index.html (accessed on 10 May 2025). |

| Trauma Resource Institute (TRI) | https://www.traumaresourceinstitute.com (accessed on 10 May 2025). |

| Health Resources and Services Administration Grantees 2022–2024: | https://bhw.hrsa.gov/funding/health-workforce-resiliency-awards (accessed on 10 May 2025). |

| https://www.nursing.emory.edu/initiatives/arrow (accessed on 10 May 2025). |

| https://www.chla.org/blog/experts/work-matters/chlas-revitalize-program-helping-team-members-preserve-their-mental-health (accessed on 10 May 2025). |

| https://iecho.org/echo-institute-programs/supporting-resilience-through-health-care (accessed on 10 May 2025). |

| https://www.uabmedicine.org/news/we-care-focuses-on-well-being/ (accessed on 10 May 2025). |

| Convent House Georgia wellness programming | https://covenanthousega.org/Health-Wellness-Services (accessed on 10 May 2025). |

| Atlanta Birth Center “Wellness Within” program | https://www.atlantabirthcenter.org/ (accessed on 10 May 2025). |

| Wake County Public School System, Counseling and Student Services Wellness workshops | Various sites such as: https://www.wakeahec.org/courses-and-events/72134/lets-come-together-lets-crm-together-community-resiliency-model (accessed on 10 May 2025). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nicholson, W.C.; Sapp, M.; Karas, E.M.; Duva, I.M.; Grabbe, L. The Body Can Balance the Score: Using a Somatic Self-Care Intervention to Support Well-Being and Promote Healing. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1258. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111258

Nicholson WC, Sapp M, Karas EM, Duva IM, Grabbe L. The Body Can Balance the Score: Using a Somatic Self-Care Intervention to Support Well-Being and Promote Healing. Healthcare. 2025; 13(11):1258. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111258

Chicago/Turabian StyleNicholson, William Chance, Michael Sapp, Elaine Miller Karas, Ingrid Margaret Duva, and Linda Grabbe. 2025. "The Body Can Balance the Score: Using a Somatic Self-Care Intervention to Support Well-Being and Promote Healing" Healthcare 13, no. 11: 1258. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111258

APA StyleNicholson, W. C., Sapp, M., Karas, E. M., Duva, I. M., & Grabbe, L. (2025). The Body Can Balance the Score: Using a Somatic Self-Care Intervention to Support Well-Being and Promote Healing. Healthcare, 13(11), 1258. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111258