Health Side Story: Scoping Review of Literature on Narrative Therapy for ADHD

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

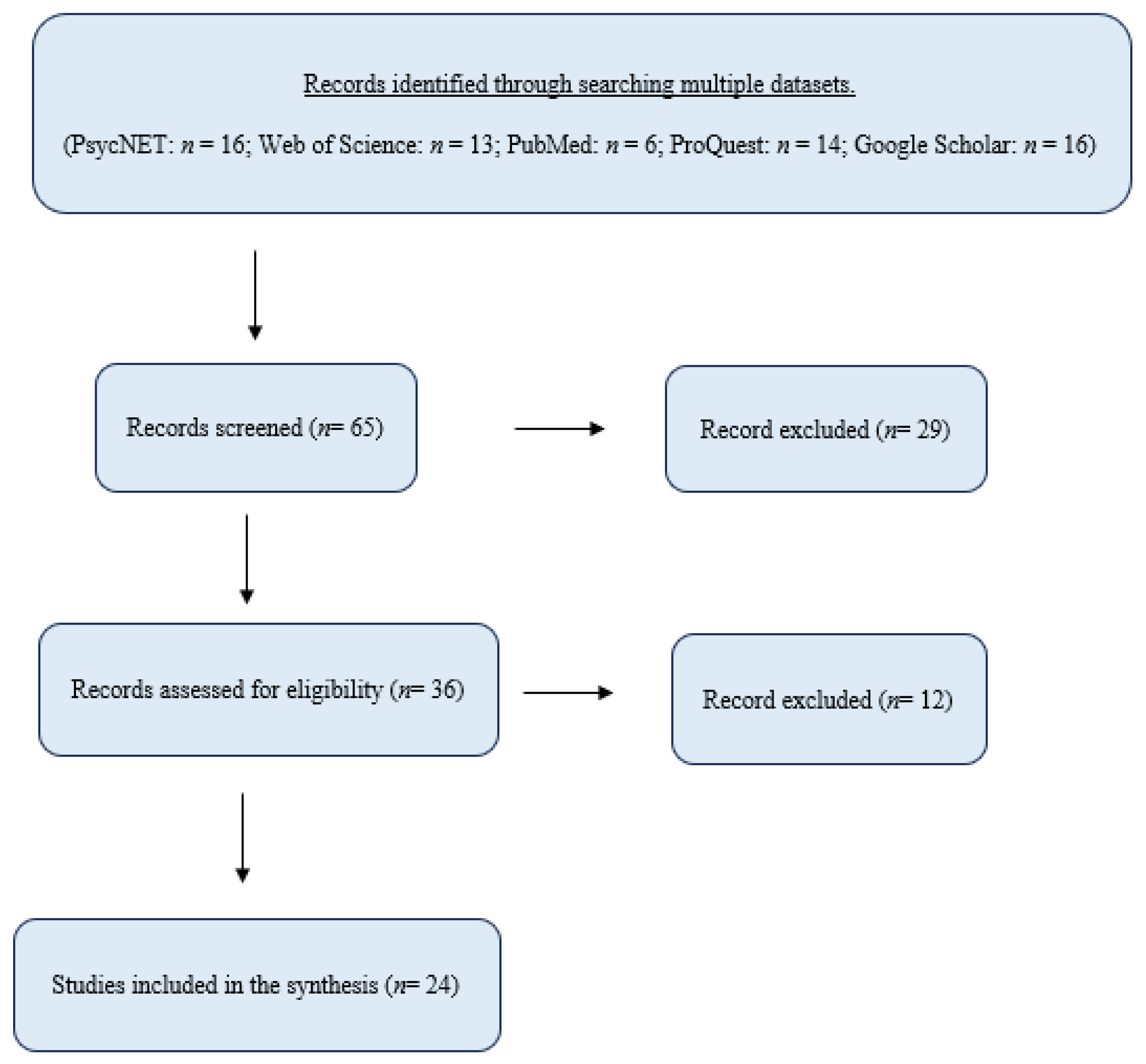

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Methods of Charting and Summarizing the Data

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Selected Records

3.2. Synthesis of the Results

3.2.1. Philosophical Foundations

Language, Meaning, and Power in Postmodern Thought

Clinical Hierarchies and the Risk of Labeling

Reimagining the Therapeutic Relationship

Language, Identity, and the Power of Re-Authoring

3.2.2. View of ADHD

3.2.3. Key Interventions and Strategies

Externalizing and Separating the Problem from the Child

Integrating Playful Communication and Metaphors

Identifying and Celebrating Unique Outcomes (‘Sparkling Moments’)

Internalizing the New (Hopeful and Empowering) Story Being Written in the Therapy

3.2.4. Reported Effectiveness

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Controversy

4.2. Future Research Directions

4.3. Potential Justifications for the Positive Reframing of ADHD

4.3.1. Potential Advantages of ADHD from Evolutionary Psychology Perspective

4.3.2. Potential Advantages of ADHD from Cognitive Neuroscience Perspective

| Authors (Year) | Title | Document Type, Publisher, and Language | Methods | Key Findings/Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dallos & Vetere, 2022 [22] | Systemic therapy and attachment narratives: Applications in a range of clinical settings. (See specifically Chapter 5) | Book, Routledge, English | This book explores how attachment-based ideas can be used in clinical practice. Chapter 5 of this book is dedicated to therapeutic work with children diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder and ADHD. This work is inspired by the narrative approach. | Key recommendations to therapists are as follows: To implement less medical terminology (e.g., energetic, spirited, enthusiastic, and alert instead of hyperactive, distracted, and uninhibited); normalize age-appropriate boisterous behaviors; soften polarized narratives that see the child as ill or bad; use externalized language and move toward less medical and problem saturated narratives; and develop narratives that emphasize the child’s strengths and competencies, thus fostering warmer feelings from their caregivers. |

| Darvish Damavandi et al., 2020 [58] | The effectiveness of narrative therapy based on daily executive functioning and on improve the cognitive emotion regulation in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder | Journal Article, Journal of Psychological Science, Persian | Quasi-experiment in which children diagnosed with ADHD (aged 9–11) were allocated to narrative therapy with executive functions training. | Narrative therapy with executive functions training decreased maladaptive strategies and increased adaptive and emotional cognitive regulatory strategies. |

| Edwards, 2022 [20] | Using a Narrative Approach to Explore Identity with Adolescents Who Have Been Given a Diagnosis of Adhd | Dissertation, University of Sheffield, English | Qualitative research among four adolescents diagnosed with ADHD. The research consisted of 4 narrative-oriented sessions with each adolescent, and the leading narrative method was ‘the bicycle of life’. The goals of these sessions were to explore the adolescents’ strengths and difficulties as well as their perceptions about their diagnosis and its effects on their sense of self. These sessions are also intended to empower the adolescents. | Narrative-oriented sessions privileged the adolescents’ authentic voice and encouraged them to identify their strengths and values (e.g., having a sense of humor, being a keen sportsman, and being an animal lover). |

| Emadian et al., 2016a [59] | Effects of Narrative Therapy and Computer-Assisted Cognitive Rehabilitation on the Reduction of ADHD Symptoms in Children | Journal Article, Journal of Babol University Of Medical Sciences, English (Iran) | Quasi-experiment in which 30 children (aged 7–12) were allocated to narrative therapy (8 sessions), computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation (10 sessions), and control (no treatment). | Narrative therapy (and computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation) was effective in reducing ADHD symptoms. |

| Emadian et al., 2016b [60] | Comparing the Effectiveness of Behavioral Management Training in Parents and Narrative Therapy in Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder on Quality of Mother-Child Relationship | Journal Article, Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Persian | Quasi-experiment in which 30 children diagnosed with ADHD (aged 7–12) and their mothers were allocated to group narrative therapy (8 sessions), behavioral management training by Barkley (9 sessions), and control (no treatment). | Both narrative therapy and behavioral management improved the quality of mother-child relationships compared to controls. No significant differences were observed between the two types of treatments. |

| Hamkins, 2008 [61] | Maps of Narrative Practice: [Review] | Book Review, Psychiatric Services, English | Review of the book “Maps of Narrative Practice” by Michael White. | In this positive book review, the author praises the content and structure of ‘this brilliant new book’ by White. The book is said to be ‘an important text by a master’. Overall, the narrative approach, which is presented in a ‘rigorous and graceful’ manner in the book, strives to move clients ‘from a problem-saturated identity to a value-based identity that supports actions’. In this way, clients can ‘free themselves from their problems’. |

| Han et al., 2015 [62] | The Effects of Narrative Therapy for Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder | Journal Article, Journal of Korean Neuropsychiatric Association, Korean | Quasi experiment in which 16 children diagnosed with ADHD were allocated to narrative therapy (6 weeks of medications and 11 sessions of narrative therapy) and medication treatment (6 weeks of medications and education for behavior controls). | Narrative therapy improved respect for children in parent-child interactions and children’s self-control (compared to the medication group). |

| Hosseinnezhad et al., 2020 [63] | Comparison of the Effectiveness of Anger Management Training based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Approach and Narrative Therapy on Academic Self- efficiency and Academic Resilience in Students with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) | Journal Article, Quarterly journal of child mental health, Persian | Quasi-experiment in which 30 boys diagnosed with ADHD (aged 11–12) were allocated to narrative therapy (8 sessions), anger management training (12 sessions), and control (no treatment). | Narrative therapy improved academic self-efficacy by the end of the treatment and in a 2-month follow-up (compared even to anger management). |

| Jacobs, 2001 [29] | Treating Huckleberry Finn: A new narrative approach to working with kids diagnosed ADD/ADHD. | Book Review, American Journal of Psychotherapy, English | Review of the book “Treating Huckleberry Finn: A New Narrative Approach Working with Kids Diagnosed ADD/ADHD” by David Nylund. | Although the author finds value in the clinical part of the book (which is said to reflect ‘a very compassionate, engaging, and innovative approach’), the book review is mostly negative. The book, according to this reviewer, provides an unjust criticism of the diagnosis and romanticizes the problem, and its author (Nylund) is accused of ignoring scientific evidence, contradicting himself, politicizing the discourse, using scare tactics, and providing misinformation. |

| Jenkins, 2001 [30] | Treating Huckleberry Finn: A new narrative approach to working with kids diagnosed ADD/ADHD. | Book Review, Psychiatric Services, English | Review of the book “Treating Huckleberry Finn: A New Narrative Approach Working with Kids Diagnosed ADD/ADHD” by David Nylund. | The author recognizes ‘some interesting and useful therapy techniques’ in the book by Nylund, but the book review is completely negative. The book, according to this reviewer, “contains logical errors and specious arguments, and it misrepresents current scientific and medical practice”. It also lacks convincing evidence that could support the efficacy of the proposed treatment. Correspondingly, its author (Nylund) is accused of promoting a conspiracy without evidence and repeating ‘tired old claims’. |

| Karibwende et al., 2023 [23] | Efficacy of narrative therapy for orphan and abandoned children with anxiety and attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders in Rwanda: A randomized controlled trial. | Journal Article, Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, English | Randomized controlled trial in which 72 children (mean age = 10) were allocated to group narrative therapy (10 sessions, 12 children in a group) and control (waiting list). | Narrative therapy was found to be effective for ADHD with large effect size. The article also provides a table with detailed descriptions of each one of the 10 sessions of the therapy. |

| Looyeh et al., 2012 [26] | An exploratory study of the effectiveness of group narrative therapy on the school behavior of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity symptoms. | Journal Article, Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, English (Iran) | Exploratory study in which 14 girls (aged 9–11) were allocated to narrative therapy (12 sessions) and control (waiting list). | Narrative therapy had a significant effect on reducing ADHD symptoms 1 week after completion of treatment. The effect was sustained after 30 days. |

| Mancuso & Yelich, 2003 [64] | Review of Treating Huckleberry Finn: A Narrative Approach To Working With Kids Diagnosed ADD/ADHD. | Book Review, Journal of Constructivist Psychology, English | Review of the book “Treating Huckleberry Finn: A New Narrative Approach Working with Kids Diagnosed ADD/ADHD” by David Nylund. | This in-depth book review endorses Nylund’s work and positions it within the field of constructivist psychology. The authors explain that the book corroborates and complements their previous work on the ‘inadequacy’ of the diagnostic label of ADHD and present its key therapeutic steps in detail. |

| Moradian et al., 2014 [28] | The effectiveness of narrative therapy based on executive functions on the improvement of inhibition and planning/organizing performance of students with ADHD | Journal Article, Journal of School Psychology and Institutions, Persian | Quasi-experiment in which 20 boys diagnosed with ADHD (aged 7–10) were allocated to narrative therapy, which incorporated executive functions training (14 sessions) and control (waiting list). | Narrative therapy with executive functions training improved inhibition and planning/organizing behaviors. |

| Morrison, 2020 [15] | Speaking ourselves quickly into meaning: social work praxis, narrative therapy, and women with ADHD | Dissertation, University of the Fraser Valley, English | Thematic literature review of the following search terms: ‘women ADHD’, ‘narrative therapy ADHD’, ‘narrative therapy social justice’, ‘social justice ADHD’, ‘social construction ADHD’, ‘feminism and narrative therapy’, and ‘narrative therapy praxis’. ADHD-related literature was confined to records published since 2010. Narrative therapy-related literature was confined to records published since 2000. | The authors reviewed 22 records and discuss two main topics: ‘narrative therapy and social justice’ and ‘women and ADHD’. The themes of the first topic were ‘narrative therapy and anti-oppressive practice’, ‘externalization as a social justice process’, and ‘externalization as highlighting personal agency’. The themes of the second topic were ‘psychiatric language and discourse’, ‘discursive gender oppression and ADHD’, ‘identity formation and ADHD’, and ‘diagnosis as an emergent event for change’. |

| Niemann, 2022 [21] | A Narrative Pastoral Counselling Approach to Giving a Voice to Children with ADHD with Anxiety | Dissertation, University of Pretoria, English | Qualitative literature investigation that aims to identify or develop a pastoral-narrative approach to ADHD children who suffer from anxiety (the principles of narrative therapy were applied to improve pastoral counseling for this population). | Narrative therapy (in the context of pastoral counseling) may help decrease the anxiety of ADHD children and lend meaning and support to their parents. |

| Nylund, 2000 [12] | Treating Huckleberry Finn: A new narrative approach to working with kids diagnosed ADD/ADHD. | Book, Jossey-Bass/Wiley, English | This book provides a comprehensive picture regarding the ideas and practical methods of the narrative approach in ADHD. The usage of the literary character of Huckleberry Finn (who possesses personality traits such as independency, nonconformity, and youthful innocence) echoes the social criticism embedded in Mark Twain’s book and illustrates how ADHD ‘symptoms’ can be re-framed as normative behaviors and even strengths. | Part 1 of the book outlines a critique of the ruling, bio-medical perception of ADHD, and part 2 elaborates on the solution offered by narrative therapy. This solution received the acronym SMART: Separating the problem from the child, Mapping the influence of ADHD, Attending to exceptions to the ADHD story, Reclaiming special abilities of diagnosed children, and Telling and celebrating the new story. |

| Nylund & Corsiglia, 1996 [19] | From deficits to special abilities: Working narratively with children labeled ‘ADHD.’ | Chapter, Guilford Press, English | The book chapter discusses the theoretical ideas that underlie the narrative approach and presents in detail how narrative therapy is applied among children diagnosed with ADHD. | Key narrative therapy interventions for ADHD are presented alongside two clinical case examples that illustrate the basic ideas of the therapy (while contrasting them to the more traditional psychiatric approach). |

| Panahifar & Nouriani, 2021 [27] | The Effectiveness of Narrative Therapy on Behavioral Maladaptation and Psychological Health of Children with ADHD in Kerman | Journal Article, Iranian Journal of Pediatric Nursing, Persian | Quasi-experiment in which 30 children (aged 7–12) were allocated to narrative therapy (10 sessions) and control (no treatment). | Narrative therapy reduced behavioral maladaptation and increased the psychological health of children with ADHD. |

| Pedraza-Vargas et al., 2009 [65] | Narrative therapy in the co-construction of experience and family coping when facing an ADHD diagnosis | Journal Article, Universitas Psychologica, Spanish | Qualitative study among three families that have a child diagnosed with ADHD. The analysis of the families’ reports was conducted through the prism of narrative therapy. | The diagnosis of ADHD seemed to have led the families to construct a (problematic) dominant narrative that focused on the child’s symptoms and attracted prejudices and negative beliefs as well as parental guilt. |

| Realmuto & Lindberg, 2001 [31] | Treating Huckleberry Finn: A new narrative approach to working with kids diagnosed ADD/ADHD. | Book Review, Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, English | Review of the book “Treating Huckleberry Finn: A New Narrative Approach Working with Kids Diagnosed ADD/ADHD” by David Nylund. | This book review presents a relatively balanced position, with a slight tendency toward negativity. The authors appreciate the narrative approach and recommend considering some of its components in psychiatric care. However, they strongly oppose Nylund’s critical viewpoint of psychiatry and warn of its potential harm. |

| Rowlands, 2017 [24] | Through all them four letters, changes everything’: an exploration of the lived experience of children, with a diagnosis of ADHD, and their parents | Dissertation, University of Birmingham, English | Qualitative interviews with four children diagnosed with ADHD and one of their parents. In the spirit of narrative therapy, the interviews sought to separate the person from the problem (i.e., ADHD) and explore its effects on the interviewees. | The interviews with the children yielded two superordinate themes: ‘stories of suspicion, silence, and exclusion’ and ‘the way ADHD was perceived, experienced, and managed’ (corresponding subordinate themes can be found in Table 6.1 of the doctoral thesis). The interviews with the children yielded two superordinate themes: ‘stories of suspicion, silence, and exclusion’ and ‘the way ADHD was perceived, experienced, and managed’ (corresponding subordinate themes can be found in Table 6.1 of the doctoral thesis). The interviews with the parents yielded three superordinate themes: ‘a journey of pleading, proving, and compliance’, ‘stories of acceptance and validation’, and ‘ADHD is hard to live with’ (corresponding subordinate themes can be found in Table 7.1 of the doctoral thesis). |

| St James O’Connor et al., 1997 [66] | On the right track: Client experience of narrative therapy. | Journal Article, Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal, English | Qualitative research in which eight families that received narrative therapy were interviewed. The children (aged 6–13) of these families experienced a range of problems, including, for example, violence, school problems, grief, and ADHD. | The interviews yielded six major themes, including, for example, externalization, developing an alternate story, and personal agency. The therapy, according to the families, was ‘very effective’. |

| Thomas, 2004 [25] | Existential/experiential approaches to child and family psychotherapy (Chapter 4 in Comprehensive Handbook of Psychotherapy) | Chapter, John Wiley & Sons Inc., English | This book chapter reviews existential-experiential approaches to child and family psychotherapy. Three major approaches are discussed: ‘symbolic-experiential family therapy’, ‘emotionally focused family therapy’, and ‘narrative therapy’. The application of these approaches is discussed within a range of conditions, including, for example, sexual abuse, depression, parental divorce, and ADHD. | Basic principles of narrative therapy are presented alongside five leading methods in the treatment of children: externalization, playfulness, and creativity working with parents, collaborative coauthoring stories with clients, developing a counterplot to the problem-saturated story, and writing letters. |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harari, L.; Oselin, S.S.; Link, B.G. The power of self-labels: Examining self-esteem consequences for youth with mental health problems. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2023, 64, 578–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennig, T.; Reininger, K.M.; Schütt, M.L.; Doll, J.; Ricken, G. Essentialist beliefs about attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): An empirical study with preservice teachers. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2023, 28, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perricone, A.; Ahn, W.K. Reasons for the belief that psychotherapy is less effective for biologically attributed mental disorders. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2024, 48, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.J. Self-fulfilling prophecies in the clinical context: Review and implications for clinical practice. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 1994, 3, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, T.; Abajobir, A.A.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdulkader, R.S.; Abdulle, A.M.; Abebo, T.A.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1211–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA (American Psychiatric Association). APA Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; Text Revision (DSM-5-TR); American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kooij, J.J.; Bijlenga, D.; Salerno, L.; Jaeschke, R.; Bitter, I.; Balazs, J.; Thome, J.; Dom, G.; Kasper, S.; Filipe, C.N.; et al. Updated European Consensus Statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 56, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R.A. International consensus statement on ADHD. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2002, 41, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R.A. This Is How You Treat ADHD Based off Science, Dr Russell Barkley Part of 2012 Burnett Lecture. Keynote Lecture at the 2012 Burnett Seminar for Academic Achievement. 2012. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_tpB-B8BXk0 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Madigan, S. Recent Developments and Future Directions in Narrative Therapy. In Narrative Therapy, 2nd ed.; Madigan, S., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 117–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavibazou, E.; Hosseinian, S.; Ale Ebrahim, N. Narrative Therapy, Applications, and Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Prev. Couns. 2022, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, D. Treating Huckleberry Finn: A New Narrative Approach to Working with Kids Diagnosed ADD/ADHD; Jossey-Bass/Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000; 234p. [Google Scholar]

- Madigan, S. Narrative Therapy; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- White, M. Maps of Narrative Practice; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2024; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, K. Speaking Ourselves Quickly into Meaning: Social Work Praxis, Narrative Therapy, and Women with ADHD. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of the Fraser Valley, Abbotsford, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Prod. ESRC Methods Programme Version 2006, 1, b92. [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A.D.; Akl, E.A.; Kunz, R.; Vist, G.; Brozek, J.; Norris, S.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Glasziou, P.; DeBeer, H.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nylund, D.; Corsiglia, V. From deficits to special abilities: Working narratively with children labeled “ADHD”. Constr. Ther. 1996, 2, 163–183. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, N. Using a Narrative Approach to Explore Identity with Adolescents Who Have Been Given a Diagnosis of ADHD. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Niemann, A.S. A Narrative Pastoral Counselling Approach to Giving a Voice to Children with ADHD with Anxiety. Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria (South Africa), Pretoria, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dallos, R.; Vetere, A. Systemic Therapy and Attachment Narratives: Applications in a Range of Clinical Settings, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Karibwende, F.; Niyonsenga, J.; Biracyaza, E.; Nyirinkwaya, S.; Hitayezu, I.; Sebatukura, G.S.; Ntete, J.M.; Mutabaruka, J. Efficacy of narrative therapy for orphan and abandoned children with anxiety and attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders in Rwanda: A randomized controlled trial. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2023, 78, 101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowlands, L.A. ‘Through All Them Four Letters, Changes Everything’: An Exploration of the Lived Experience of Children, with a Diagnosis of ADHD, and Their Parents. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, V. Existential/Experiential Approaches to Child and Family Psychotherapy. Compr. Handb. Psychother. Interpers./Humanist./Existent. 2004, 3, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Looyeh, M.Y.; Kamali, K.; Shafieian, R. An exploratory study of the effectiveness of group narrative therapy on the school behavior of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity symptoms. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2012, 26, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahifar, S.; Nouriani, J.M. The Effectiveness of Narrative therapy on Behavioral Maladaptation and Psychological Health of Children with ADHD in Kerman. Iran. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 8, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Moradian, Z.; Mashhadi, A.; Aghamohammadian, H.; Asghari Nekah, M. The effectiveness of narrative therapy based on executive functions on the improvement of inhibition and planning/organizing performance of student with ADHD. J. Sch. Psychol. 2014, 3, 186–204. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, E.H. Treating Huckleberry Finn: A New Narrative Approach to Working with Kids Diagnosed ADD/ADHD. Am. J. Psychother. 2001, 55, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, S.C. Treating Huckleberry Finn: A New Narrative Approach to Working With Kids Diagnosed ADD/ADHD• Unraveling the Mystery of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorder: A Mother’s Story of Research and Recovery. Psychiatr. Serv. 2001, 52, 697–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, D. [BOOK REVIEW] Treating Huckleberry Finn, a new narrative approach to working with kids diagnosed ADD/ADHD. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 612–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophir, Y. ADHD Is Not an Illness and Ritalin Is Not a Cure: A Comprehensive Rebuttal of the (Alleged) Scientific Consensus; World Scientific: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Conners, C.K.; Sitarenios, G.; Parker, J.D.; Epstein, J.N. The revised Conners’ Parent Rating Scale (CPRS-R): Factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1998, 26, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraone, S.V.; Banaschewski, T.; Coghill, D.; Zheng, Y.; Biederman, J.; Bellgrove, M.A.; Newcorn, J.H.; Gignac, M.; Al Saud, N.M.; Manor, I.; et al. The world federation of ADHD international consensus statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 128, 789–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, H.A.; Shah, P. Uninhibited imaginations: Creativity in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 40, 1121–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.; Windmann, S.; Siefen, R.; Daum, I.; Güntürkün, O. Creative thinking in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Child Neuropsychol. 2006, 12, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogman, M.; Stolte, M.; Baas, M.; Kroesbergen, E. Creativity and ADHD: A review of behavioral studies, the effect of psychostimulants and neural underpinnings. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 119, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, J.A.; Merwood, A.; Asherson, P. The positive aspects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A qualitative investigation of successful adults with ADHD. ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord. 2019, 11, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, D. The ADHD Advantage: What You Thought Was a Diagnosis May Be Your Greatest Strength; Avery: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lasky, A.K.; Weisner, T.S.; Jensen, P.S.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Hechtman, L.; Arnold, L.E.; Murray, D.W.; Swanson, J.M. ADHD in context: Young adults’ reports of the impact of occupational environment on the manifestation of ADHD. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 161, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, V.J.; Butler, J.; Marra, D. The relationship between symptoms of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder with soldier performance during training. Work 2013, 44 (Suppl. S1), 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olinover, M.; Gidron, M.; Yarmolovsky, J.; Geva, R. Strategies for improving decision making of leaders with ADHD and without ADHD in combat military context. Leadersh. Q. 2022, 33, 101575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, K.S.; Weatherly, J.N. The relationship between personality traits and military enlistment: An exploratory study. Mil. Behav. Health 2014, 2, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T. ADHD: A Hunter in a Farmer’s World; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Swanepoel, A.; Music, G.; Launer, J.; Reiss, M.J. How evolutionary thinking can help us to understand ADHD. BJPsych Adv. 2017, 23, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley-Tremblay, J.F.; Rosen, L.A. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: An evolutionary perspective. J. Genet. Psychol. 1996, 157, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, E.S.; Hoffman, Y.S.; Berger, I.; Zivotofsky, A.Z. Beating their chests: University students with ADHD demonstrate greater attentional abilities on an inattentional blindness paradigm. Neuropsychology 2015, 29, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Simons, D.J.; Chabris, C.F. Gorillas in our midst: Sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events. Perception 1999, 28, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Yu, W.; Tucker, R.; Marino, L.D. ADHD, impulsivity and entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 627–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Patzelt, H.; Dimov, D. Entrepreneurship and psychological disorders: How ADHD can be productively harnessed. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2016, 6, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheul, I.; Block, J.; Burmeister-Lamp, K.; Thurik, R.; Tiemeier, H.; Turturea, R. ADHD-like behavior and entrepreneurial intentions. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 45, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, D.A.; Verheul, I.; Thurik, R. Entrepreneurship and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A large-scale study involving the clinical condition of ADHD. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 53, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysikou, E.G. Creativity in and out of (cognitive) control. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2019, 27, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot, N.; Nevicka, B.; Baas, M. Subclinical symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are associated with specific creative processes. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 114, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberstein, R.; Camfield, D.A.; Nield, G.; Stough, C. Gender differences in parieto-frontal brain functional connectivity correlates of creativity. Brain Behav. 2019, 9, e01196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topolinski, S.; Reber, R. Gaining insight into the “Aha” experience. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 19, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounios, J.; Fleck, J.I.; Green, D.L.; Payne, L.; Stevenson, J.L.; Bowden, E.M.; Jung-Beeman, M. The origins of insight in resting-state brain activity. Neuropsychologia 2008, 46, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darvish Damavandi, Z.; Dortaj, F.; Ghanbari Hashem Abadi, B.A.; Delavar, A. The effectiveness of narrative therapy based on daily executive functioning and on improve the cognitive emotion regulation in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 19, 787–797. [Google Scholar]

- Emadian, S.O.; Bahrami, H.; Hassanzadeh, R.; Banijamali, S. Effects of narrative therapy and computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation on the reduction of ADHD symptoms in children. J. Babol Univ. Med. Sci. 2016, 18, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Emadian, S.O.; Bahrami, H.; Hassanzadeh, R.; Banijamali, S. Comparing the effectiveness of behavioral management training in parents and narrative therapy in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder on quality of mother-child relationship. J. Maz. Univ. Med. Sci. 2016, 26, 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hamkins, S. Maps of Narrative Practice. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008, 59, 941–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.W.; Hyun, M.H.; Han, D.H.; Son, J.H.; Kim, S.M.; Bae, S. The effects of narrative therapy for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 2015, 54, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinnezhad, A.; Abolghasemi, S.; Vatankhah, H.R.; Khalatbari, J. Comparison of the effectiveness of anger management training based on cognitive behavioral therapy approach and narrative therapy on academic self-efficiency and academic resilience in students with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Q. J. Child Ment. Health 2020, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, J.C.; Yelich, G.A. Review of treating Huckleberry Finn: A new narrative approach to working with kids diagnosed ADD/ADHD. J. Constr. Psychol. 2003, 16, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza-Vargas, S.F.; Perdomo-Carvajal, M.F.; Hernández-Manrique, N.J. Terapia narrativa en la co-construcción de la experiencia y el afrontamiento familiar en torno a la impresion diagnóstica de TDAH. [Narrative therapy in the co-construction of experience and family coping when facing an ADHD diagnosis.]. Univ. Psychol. 2009, 8, 199–214. [Google Scholar]

- St James O’Connor, T.; Meakes, E.; Pickering, M.R.; Schuman, M. On the right track: Client experience of narrative therapy. Contemp. Fam. Ther. Int. J. 1997, 19, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophir, Y. Reevaluating ADHD and its first-line treatment: Insights from DSM-5-TR and modern approaches. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2024, 21, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophir, Y.; Shir-Raz, Y. Discrepancies in Studies on ADHD and COVID-19 Raise Concerns Regarding the Risks of Stimulant Treatments During an Active Pandemic. Ethical Hum. Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 25, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophir, Y. Reconsidering the safety profile of stimulant medications for ADHD. Ethical Hum. Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 24, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophir, Y. Evidence that the diagnosis of ADHD does not reflect a chronic bio-medical disease. Ethical Hum. Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 23, 100–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ophir, Y.; Rosenberg, H.; Tikochinski, R.; Efrati, Y. Health Side Story: Scoping Review of Literature on Narrative Therapy for ADHD. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1247. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111247

Ophir Y, Rosenberg H, Tikochinski R, Efrati Y. Health Side Story: Scoping Review of Literature on Narrative Therapy for ADHD. Healthcare. 2025; 13(11):1247. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111247

Chicago/Turabian StyleOphir, Yaakov, Hananel Rosenberg, Refael Tikochinski, and Yaniv Efrati. 2025. "Health Side Story: Scoping Review of Literature on Narrative Therapy for ADHD" Healthcare 13, no. 11: 1247. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111247

APA StyleOphir, Y., Rosenberg, H., Tikochinski, R., & Efrati, Y. (2025). Health Side Story: Scoping Review of Literature on Narrative Therapy for ADHD. Healthcare, 13(11), 1247. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111247