The Comprehension, Cosmetics, Convenience, Content, and Credibility of Infographic Patient Information Leaflets (iPILs) Compared to Existing PILs (ePILs)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

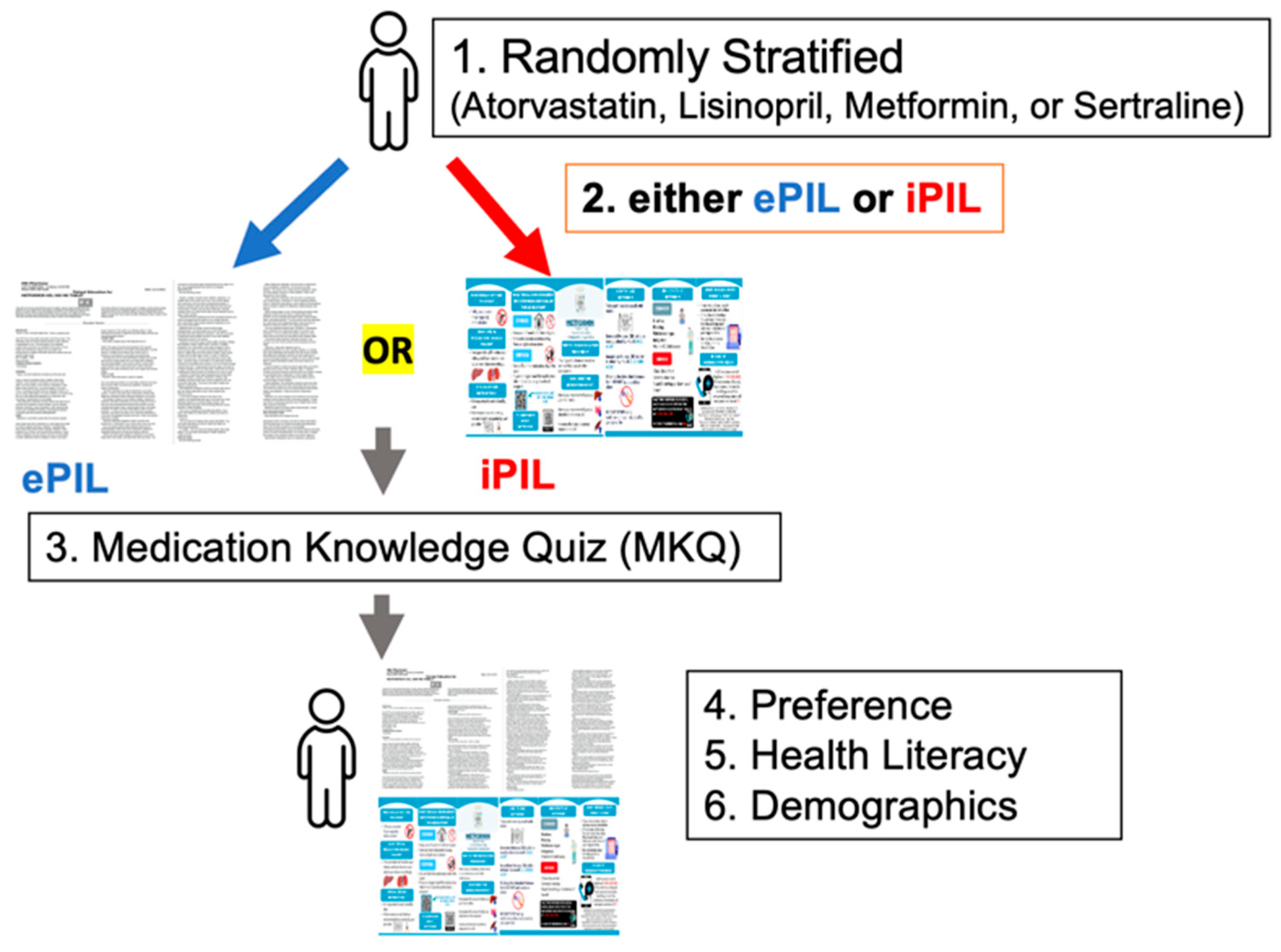

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Data Collection Tool and Infographic-Based PILs (iPILs)

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Outcome Measures

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Medication Knowledge Quiz Assessing Comprehension

3.3. Association Between Comprehension Score and Health Literacy

3.4. Associations of Comprehension Score with PIL Version and Language

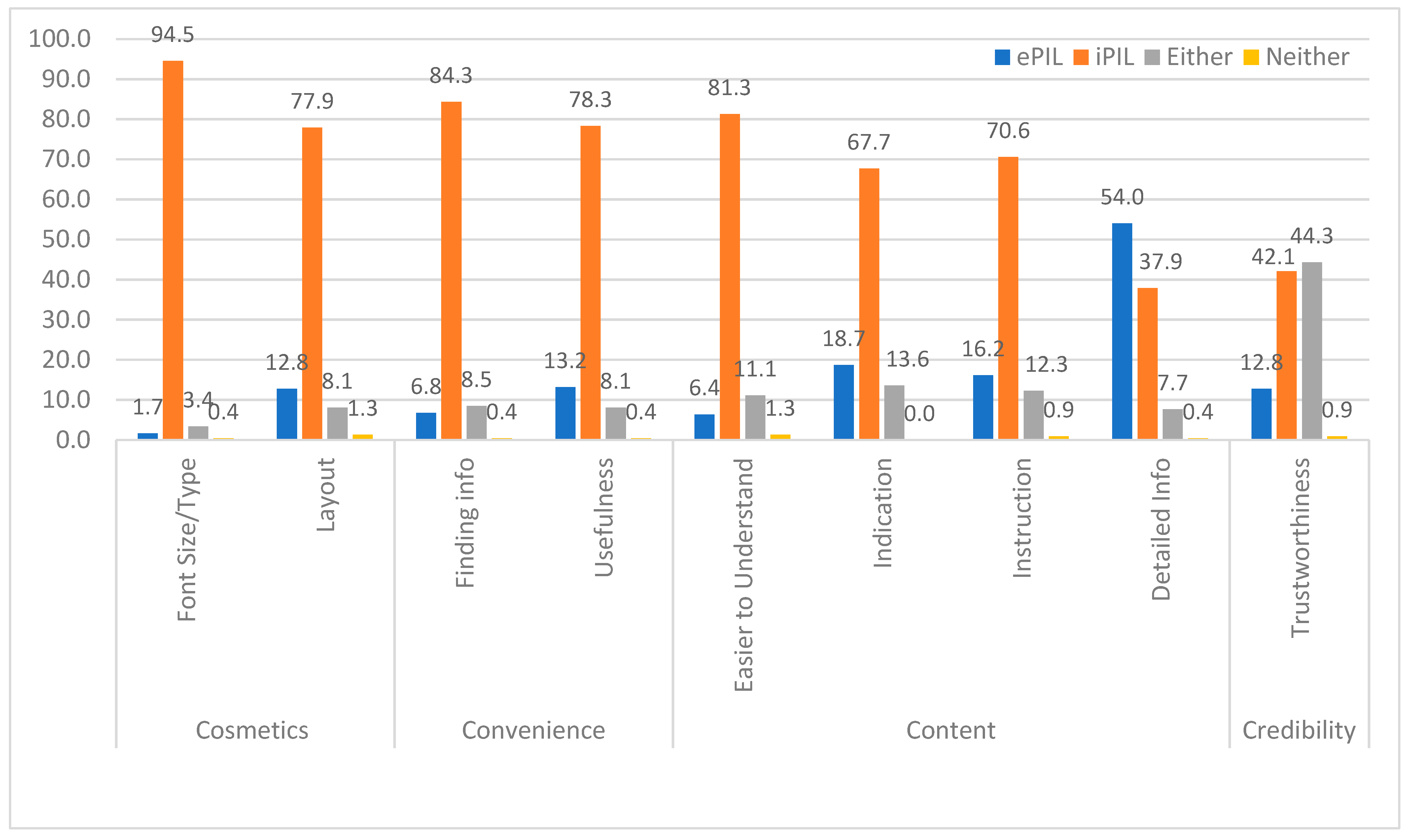

3.5. Preference Across Four Factors: Cosmetics, Convenience, Content, and Credibility

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PILs | Patient Information Leaflets |

| iPILs | Infographic-based Patient Information Leaflets |

| ePILs | Existing Patient Information Leaflets |

| PMI | Patient Medication Information |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| LEP | Low English Proficiency |

| Q&A | Question and Answer |

| CA | California |

| IL | Illinois |

| MKQ | Medication Knowledge Quiz |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

References

- Nathan, J.P.; Zerilli, T.; Cicero, L.A.; Rosenberg, J.M. Patients’ use and perception of medication information leaflets. Ann. Pharmacother. 2007, 41, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patient Medication Information (PMI). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fdas-labeling-resources-human-prescription-drugs/patient-medication-information-pmi (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Liu, F.; Abdul-Hussain, S.; Mahboob, S.; Rai, V.; Kostrzewski, A. How useful are medication patient information leaflets to older adults? A content, readability and layout analysis. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2014, 36, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raynor, D.K.; Blenkinsopp, A.; Knapp, P.; Grime, J.; Nicolson, D.J.; Pollock, K.; Dorer, G.; Gilbody, S.; Dickinson, D.; Maule, A.J.; et al. A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative research on the role and effectiveness of written information available to patients about individual medicines. Health Technol. Assess. 2007, 11, 1–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wali, H.; Hudani, Z.; Wali, S.; Mercer, K.; Grindrod, K. A systematic review of interventions to improve medication information for low health literate populations. Res. Social. Adm. Pharm. 2016, 12, 830–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jeraisy, M.; Alshammari, H.; Albassam, M.; Al Aamer, K.; Abolfotouh, M.A. Utility of patient information leaflet and perceived impact of its use on medication adherence. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, C.A.; Kleinman, D.V.; Pronk, N.; Wrenn Gordon, G.L.; Ochiai, E.; Blakey, C.; Johnson, A.; Brewer, K.H. Addressing Health Equity and Social Determinants of Health Through Healthy People 2030. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2021, 27, S249–S257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Literacy in Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/health-literacy-healthy-people-2030 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Hammar, T.; Nilsson, A.L.; Hovstadius, B. Patients’ views on electronic patient information leaflets. Pharm. Pract. 2016, 14, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beusekom, M.M.; Grootens-Wiegers, P.; Bos, M.J.; Guchelaar, H.J.; van den Broek, J.M. Low literacy and written drug information: Information-seeking, leaflet evaluation and preferences, and roles for images. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2016, 38, 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisholm-Burns, M.A.; Spivey, C.A. The ‘cost’ of medication nonadherence: Consequences we cannot afford to accept. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2012, 52, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, R.L.; Fernandez-Llimos, F.; Frommer, M.; Benrimoj, C.; Garcia-Cardenas, V. Economic impact of medication non-adherence by disease groups: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e016982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, A.V.; Zargarzadeh, A.H. How do patients read, understand and use prescription labels? An exploratory study examining patient and pharmacist perspectives. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2010, 18, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zargarzadeh, A.H.; Law, A.V. Design and test of preference for a new prescription medication label. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2011, 33, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007, 335, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Literacy Tool Shed. Available online: https://healthliteracy.tuftsmedicine.org/about (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- McHugh, M.L. Descriptive statistics, Part II: Most commonly used descriptive statistics. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2003, 8, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Boudewyns, V.; O’Donoghue, A.C.; Kelly, B.; West, S.L.; Oguntimein, O.; Bann, C.M.; McCormack, L.A. Influence of patient medication information format on comprehension and application of medication information: A randomized, controlled experiment. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herber, O.R.; Gies, V.; Schwappach, D.; Thürmann, P.; Wilm, S. Patient information leaflets: Informing or frightening? A focus group study exploring patients’ emotional reactions and subsequent behavior towards package leaflets of commonly prescribed medications in family practices. BMC Fam. Pract. 2014, 15, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinker, S.; Eliyahu, V.; Yaphe, J. The effect of drug information leaflets on patient behavior. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2007, 9, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Robert, M.; Califf, M.D.; MACC. FDA Proposes New, Easy-to-Read Medication Guide for Patients, Patient Medication Information. 2023; U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-proposes-new-easy-read-medication-guide-patients-patient-medication-information (accessed on 10 May 2025).

| Characteristics | CA-English | IL-English | CA-Spanish | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 105) | (n = 62) | (n = 68) | ||

| Age, n (%) | ||||

| 18–34 | 1 (1.0%) | 13 (21.0%) | 9 (13.2%) | <0.001 |

| 35–54 | 31 (29.5%) | 24 (38.7%) | 33 (48.5%) | |

| 54+ | 73 (69.5%) | 22 (35.5%) | 26 (38.2%) | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 0 (0%) | 3 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 35 (33.3%) | 22 (35.5%) | 21 (30.9%) | 0.191 |

| Female | 70 (66.7%) | 38 (61.3%) | 47 (69.1%) | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 38 (36.2%) | 9 (15.5%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Black | 13 (12.4%) | 44 (75.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Hispanic | 38 (36.2%) | 3 (5.2%) | 68 (100%) | |

| Asian | 8 (7.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| American Indian/Alaska native | 2 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 4 (3.8%) | 1 (1.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (1.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Missing | 0 | 4 | 0 | |

| Education level, n (%) | ||||

| Less than high school | 2 (1.9%) | 5 (8.1%) | 22 (32.4%) | <0.001 |

| High school diploma | 17 (16.2%) | 30 (48.4%) | 31 (45.6%) | |

| Some college | 49 (46.7%) | 17 (27.4%) | 10 (14.7%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 22 (21.0%) | 4 (6.5%) | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 14 (13.3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Other/prefer not to disclose | 1 (1.0%) | 6 (9.7%) | 1 (1.5%) | |

| Annual income, n (%) | ||||

| Disabled/unemployed | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (8.8%) | <0.001 |

| ≤$25,000 | 19 (18.1%) | 18 (29.0%) | 18 (26.5%) | |

| $25,000–49,999 | 29 (27.6%) | 17 (27.4%) | 29 (4.6%) | |

| $50,000–99,999 | 20 (19.0%) | 5 (8.1%) | 4 (5.9%) | |

| $100,000–149,999 | 13 (12.4%) | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (1.5%) | |

| ≥$150,000 | 13 (12.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 11 (10.5%) | 21 (33.9%) | 10 (14.7%) | |

| Insurance plan type, n (%) | ||||

| None | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (11.8%) | <0.001 |

| Medicare only | 7 (6.7%) | 4 (6.5%) | 15 (22.1%) | |

| Medicaid only | 5 (4.8%) | 20 (32.3%) | 23 (33.8%) | |

| Both Medicare and Medicaid | 24 (22.9%) | 1 (1.6%) | 8 (11.8%) | |

| Private insurance only | 44 (41.9%) | 24 (38.7%) | 13 (19.1%) | |

| Both private and Medicare | 16 (15.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 5 (4.8%) | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (1.5%) | |

| Not sure | 3 (2.9%) | 12 (19.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Number of health conditions (mean ± SD) | 2.08 ± 1.29 | 2.41 ± 1.07 | 1.47 ± 1.06 | <0.001 |

| Number of prescription medications, n (%) | ||||

| 1–2 med(s) | 35 (33.3%) | 14 (23.0%) | 43 (63.2%) | <0.001 |

| 3–5 meds | 44 (41.9%) | 33 (54.1%) | 20 (29.4%) | |

| 6–10 meds | 19 (18.1%) | 13 (21.3%) | 5 (7.4%) | |

| More than 10 meds | 7 (6.7%) | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Health literacy score (mean ± SD) | 13.35 ± 2.75 | 13.79 ± 2.27 | 10.87 ± 2.82 | <0.001 |

| Health literacy, n (%) Low health literacy (score 4–9) | 8 (7.6%) | 3 (4.8%) | 23 (33.8%) | <0.001 |

| High health literacy (score 10–16) | 97 (92.4%) | 59 (95.2%) | 45 (66.2%) |

| Quiz Item | Accuracy Rate a (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA-English | IL-English | CA-Spanish | |||||

| ePIL | iPIL | ePIL | iPIL | ePIL | iPIL | ||

| (n = 49) | (n = 56) | (n = 29) | (n = 33) | (n = 35) | (n = 33) | ||

| 1 | One health condition this medication is used for | 89.8 | 96.4 | 87.2 | 93.9 | 77.1 | 93.9 |

| 2 | One side effect of this medication | 75.5 | 80.4 | 72.4 * | 100.0 * | 60.0 * | 84.8 * |

| 3 | One precaution while taking this medication | 14.3 * | 50.0 * | 51.7 | 78.8 | 51.4 | 61.8 |

| 4 | Side effect needing immediate medical attention | 63.3 | 60.7 | 72.4 | 87.9 | 31.4 * | 72.7 * |

| 5 | What to avoid while taking this medication | 26.5 * | 83.9 * | 39.3 * | 84.8 * | 42.9 * | 75.8 * |

| 6 | How this medication should be stored | 87.8 | 87.5 | 86.2 * | 100.0 * | 82.9 | 87.9 |

| Comprehension score b (mean ± standard deviation) | 3.97 ± 1.28 * | 4.81 ± 1.10 * | 4.36 ± 1.78 * | 5.61 ± 0.67 * | 3.57 ± 1.41 * | 4.91 ± 1.52 * | |

| Pooled analysis | ePIL (n = 113) | iPIL (n = 122) | |||||

| 3.95 ± 1.48 * | 5.05 ± 1.18 * | ||||||

| Correlation with health literacy (r) | 0.338 * | −0.003 | 0.654 * | 0.340 | 0.177 | 0.100 | |

| Pooled analysis | ePIL (n = 113) | iPIL (n = 122) | |||||

| 0.394 * | 0.128 | ||||||

| Mean Comprehension Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Difference (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted Mean Diff. * (95% CI) | p-Value * | |

| PIL version | ||||

| ePIL | Reference | Reference | ||

| iPIL | 1.09 (0.75–1.43) | <0.001 | 1.07 (0.74–1.40) | <0.001 |

| Language | ||||

| English | Reference | Reference | ||

| Spanish | −0.37 (−0.75–0.01) | 0.053 | −0.05 (−0.51–0.41) | 0.840 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, X.; Kim, E.; Zamora, J.; Hata, M.; Wooley, A.; Devraj, R.; Gogineni, H.P.; Law, A.V. The Comprehension, Cosmetics, Convenience, Content, and Credibility of Infographic Patient Information Leaflets (iPILs) Compared to Existing PILs (ePILs). Healthcare 2025, 13, 1227. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111227

Pan X, Kim E, Zamora J, Hata M, Wooley A, Devraj R, Gogineni HP, Law AV. The Comprehension, Cosmetics, Convenience, Content, and Credibility of Infographic Patient Information Leaflets (iPILs) Compared to Existing PILs (ePILs). Healthcare. 2025; 13(11):1227. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111227

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Xin, Eunhee Kim, Jose Zamora, Micah Hata, Andrea Wooley, Radhika Devraj, Hyma P. Gogineni, and Anandi V. Law. 2025. "The Comprehension, Cosmetics, Convenience, Content, and Credibility of Infographic Patient Information Leaflets (iPILs) Compared to Existing PILs (ePILs)" Healthcare 13, no. 11: 1227. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111227

APA StylePan, X., Kim, E., Zamora, J., Hata, M., Wooley, A., Devraj, R., Gogineni, H. P., & Law, A. V. (2025). The Comprehension, Cosmetics, Convenience, Content, and Credibility of Infographic Patient Information Leaflets (iPILs) Compared to Existing PILs (ePILs). Healthcare, 13(11), 1227. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111227