Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices in Pressure Injury Prevention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

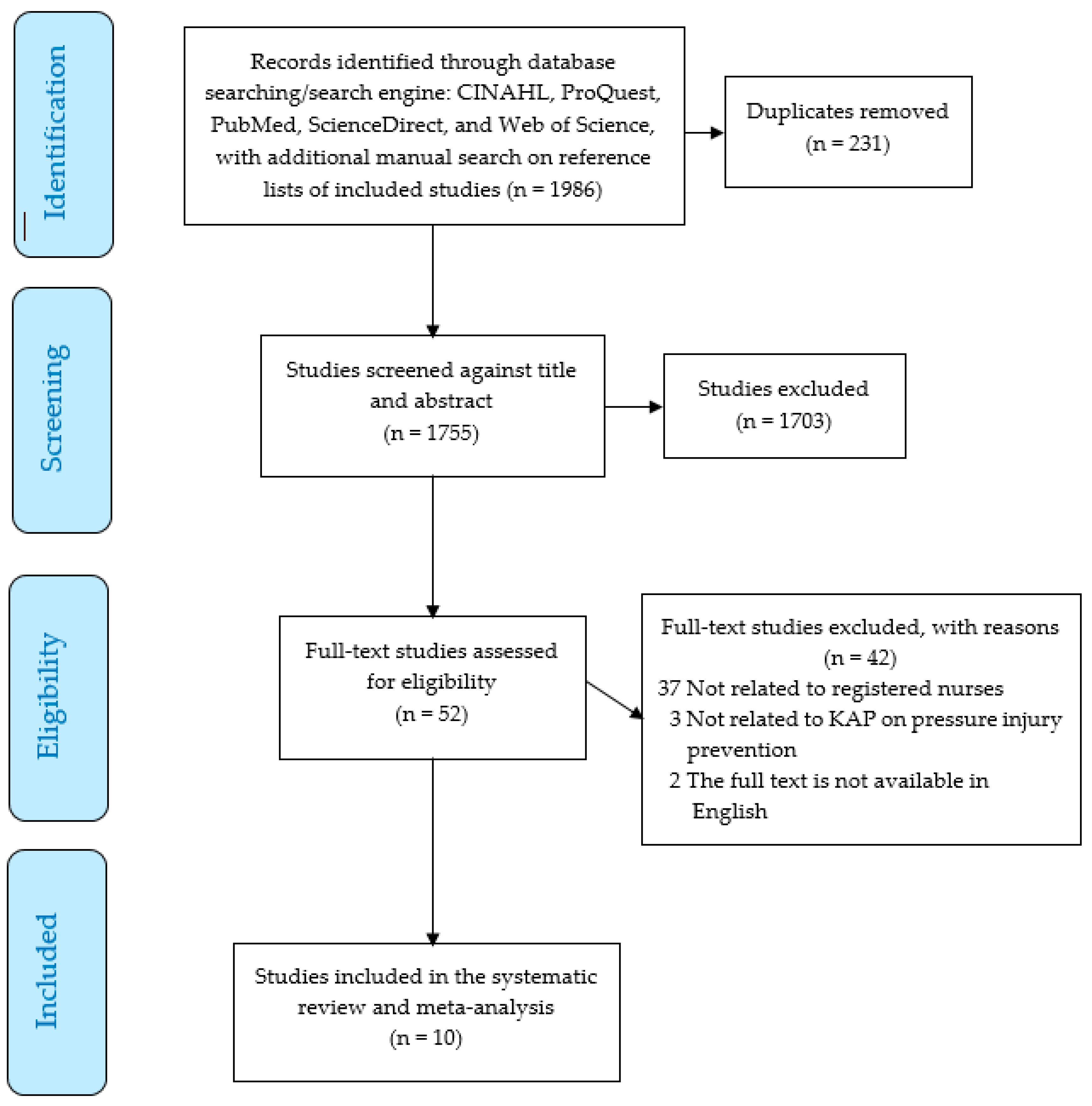

2.3. Data Selection Process

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analyses

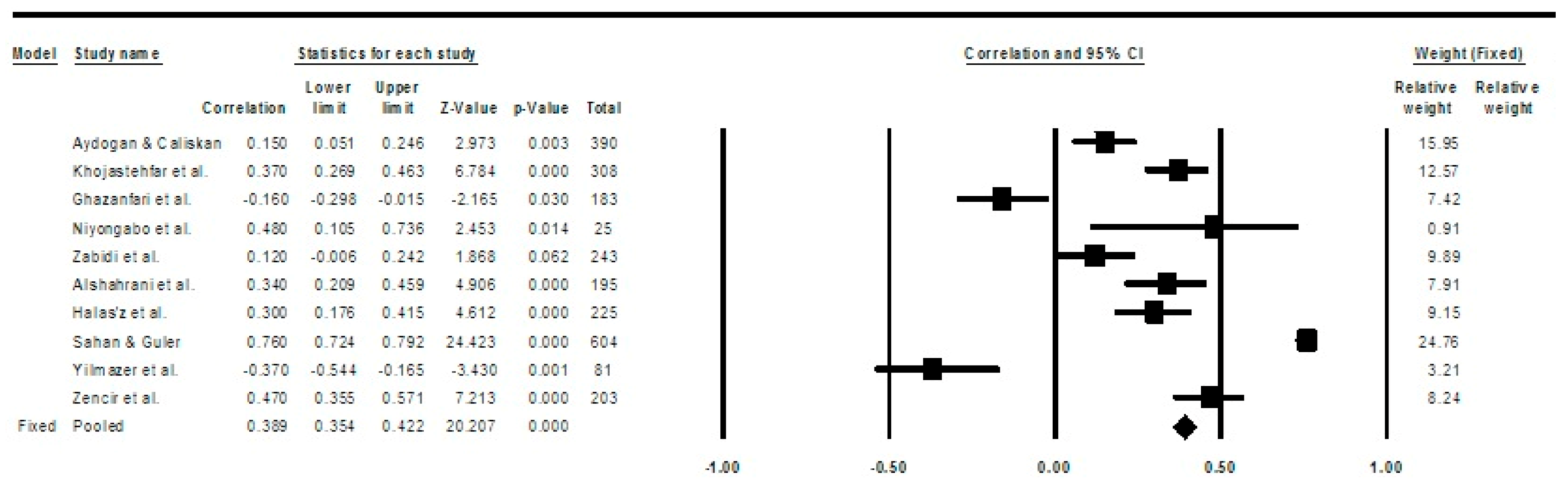

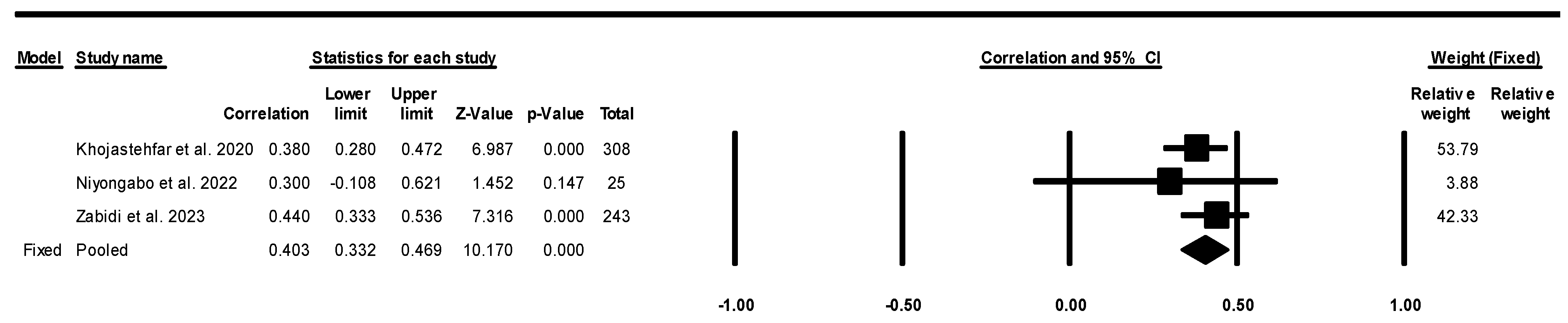

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhattacharya, S.; Mishra, R.K. Pressure ulcers: Current understanding and newer modalities of treatment. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2015, 48, 004–016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Lin, F.; Thalib, L.; Chaboyer, W. Global prevalence and incidence of pressure injuries in hospitalised adult patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 105, 103546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padula, W.V.; Delarmente, B.A. The national cost of hospital-acquired pressure injuries in the United States. Int. Wound J. 2019, 16, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siotos, C.; Bonett, A.M.; Damoulakis, G.; Becerra, A.Z.; Kokosis, G.; Hood, K.; Dorafshar, A.H.; Shenaq, D.S. Burden of Pressure Injuries: Findings From the Global Burden of Disease Study. Eplasty 2022, 22, e19. [Google Scholar]

- Wassel, C.L.; Delhougne, G.; Gayle, J.A.; Dreyfus, J.; Larson, B. Risk of readmissions, mortality, and hospital-acquired conditions across hospital-acquired pressure injury (HAPI) stages in a US National Hospital Discharge database. Int. Wound J. 2020, 17, 1924–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondragon, N.; Zito, P.M. Pressure Injury. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, B.M.; Walker, R.M.; Latimer, S.L.; Thalib, L.; A Whitty, J.; McInnes, E.; Chaboyer, W.P. Repositioning for pressure injury prevention in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, CD009958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.C.; Nain, R.A. Dataset on nurses’ knowledge, attitude and practice in pressure injury prevention at Sabah, Malaysia. Data Brief 2023, 48, 109193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A.A. Ageing in Saudi Arabia: New dimensions and intervention strategies. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mutairi, A.; Schwebius, D.; Al Mutair, A. Hospital-acquired pressure ulcer incident rates among hospitals that implement an education program for staff, patients, and family caregivers inclusive of an after discharge follow-up program in Saudi Arabia. Int. Wound J. 2020, 17, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAzmi, A.A.; Jastaniah, W.; Alhamdan, H.S.; AlYamani, A.O.; AlKhudhyr, W.I.; Abdullah, S.M.; AlZahrani, M.; AlSahafi, A.; AlOhali, T.A.; Alkhelawi, T.; et al. Addressing Cancer Treatment Shortages in Saudi Arabia: Results of a National Survey and Expert Panel Recommendations. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2020, 6, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, K.; Coren, E.; McCaffrey, M.; Slean, C. Transforming the stories we tell about climate change: From ‘issue’ to ‘action’. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 015002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvand, S.; Ebadi, A.; Gheshlagh, R.G. Nurses’ knowledge on pressure injury prevention: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on the Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Assessment Tool. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, ume 11, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyib, N.; Coyer, F.; Lewis, P. Saudi Arabian adult intensive care unit pressure ulcer incidence and risk factors: A prospective cohort study. Int. Wound J. 2016, 13, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, C.; Liu, Y.; Song, B.; Jin, J.; Liu, Y.; Wen, X.; Cheng, S.; Wu, X. Critical Care Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Pressure Injury Treatment: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Survey. Risk Manag. Health Policy 2022, ume 15, 2125–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.; Sukumar, K.; Blanchard, S.; Ramasamy, A.; Malinowski, J.; Ginex, P.; Senerth, E.; Corremans, M.; Munn, Z.; Kredo, T.; et al. Trends in guideline implementation: An updated scoping review. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coventry, L.; Towell-Barnard, A.; Winderbaum, J.; Walsh, N.; Jenkins, M.; Beeckman, D. Nurse knowledge, attitudes, and barriers to pressure injuries: A cross-sectional study in an Australian metropolitan teaching hospital. J. Tissue Viability 2024, 33, 792–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, F.K.; Sim, J.; Lapkin, S. Systematic review: Nurses’ safety attitudes and their impact on patient outcomes in acute-care hospitals. Nurs. Open 2022, 9, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavallée, J.F.; A Gray, T.; Dumville, J.C.; Cullum, N. Preventing pressure injury in nursing homes: Developing a care bundle using the Behaviour Change Wheel. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, S.E.; Ali, H.A.; El Maraghi, S.K. Effect of Educational Program about Preventive Nursing Measures of Medical devices related Pressure Injuries on Nurses’ Performance and Patients’ Clinical Outcome. Tanta Sci. Nurs. J. 2022, 27, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berihu, H.; Wubayehu, T.; Teklu, T.; Zeru, T.; Gerensea, H. Practice on pressure ulcer prevention among nurses in selected public hospitals, Tigray, Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Suárez, A.B.; Morales-Asencio, J.M.; Aranda-Gallardo, M.; de Luna-Rodríguez, M.E.; Canca-Sánchez, J.C. Development and psychometric validation of a questionnaire to evaluate nurses’ adherence to recommendations for preventing pressure ulcers (QARPPU). J. Tissue Viability 2017, 26, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuru, N.; Zewdu, F.; Amsalu, S.; Mehretie, Y. Knowledge and practice of nurses towards prevention of pressure ulcer and associated factors in Gondar University Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. 2015, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, N.; Liu, W.; Zhu, R.; Wang, C.; Wang, C.; Chi, W. A survey of knowledge, attitudes, and practices among paediatric intensive care unit nurses for preventing pressure injuries: An analysis of influencing factors. Int. Wound J. 2024, 21, e14710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Song, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Chen, S.; Lin, F. Barriers and facilitators to pressure injury prevention in hospitals: A mixed methods systematic review. J. Tissue Viability 2023, 32, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, J.; Otts, J.A.; Riley, B.; Mulekar, M.S. Pressure Injury Prevention and Management. J. Wound, Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2022, 49, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhiainen, M.; Mandzo, C.N. Nurses’ Experiences of Pressure Ulcer Prevention. Bachelor’s Thesis, Jamk University of Applied Science, Jyväskylä, Finland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Han, L. Incidence and prevalence of pressure injuries in children patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Tissue Viability 2022, 31, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoke, N.; Tekalign, T.; Arba, A.; Lenjebo, T.L. Pressure injury prevention practice and associated factors among nurses at Wolaita Sodo University Teaching and Referral Hospital, South Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e047687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazanfari, M.J.; Karkhah, S.; Maroufizadeh, S.; Fast, O.; Jafaraghaee, F.; Gholampour, M.H.; Zeydi, A.E. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of Iranian critical care nurses related to prevention of pressure ulcers: A multicenter cross-sectional study. J. Tissue Viability 2022, 31, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, E.; Kang, H. Introduction to systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2018, 71, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, D.; Dearholt, S.L.; Bissett, K.; Ascenzi, J.; Whalen, M. Johns Hopkins Evidence-Based Practice for Nurses and Healthcare Professionals: Model and Guidelines, 4th ed.; Sigma Theta Tau International: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2021; Available online: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ras/detail.action?docID=6677828 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Dialog Solutions. 2023. Available online: https://dialog.com/ (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Horsley, T.; Dingwall, O.; Sampson, M. Checking reference lists to find additional studies for systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 2011, MR000026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochrane Library. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/web/cochrane/cdsr/table-of-contents?volume=2022&issue=5 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Covidence Systematic Review Software. 2025. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Tawfik, G.M.; Dila, K.A.S.; Mohamed, M.Y.F.; Tam, D.N.H.; Kien, N.D.; Ahmed, A.M.; Huy, N.T. A step by step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data. Trop. Med. Health 2019, 47, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). JBI Appraisal Score. 2025. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Zencir, G.; Yeşilyaprak, T.; Ünal, E.P.; Akın, B.; Gök, F. Evaluation of surgical nurses’ knowledge and attitudes towards pressure ulcer prevention. J. Tissue Viability 2025, 34, 100862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahan, S.; Güler, S. Evaluating the Knowledge Levels and Attitudes Regarding Pressure Injuries among Nurses in Turkey. Adv. Ski. Wound Care 2024, 37, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, B.; Middleton, R.; Rolls, K.; Sim, J. Critical care nurses’ knowledge and attitudes toward pressure injury prevention: A pre and post intervention study. Intensiv. Crit. Care Nurs. 2023, 79, 103528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabidi, H.; Aldousari, N.; Alesawi, K.; Alkhudairy, W.; Albishry, S.; Alrashdi, S.; Alsulami, A.; Aljasim, H.; Hawsawi, B.; Mobarki, K. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Regarding Pressure Ulcer Prevention among Nurses. Int. J. Nov. Res. Healthc. Nurs. 2023, 10, 409–419. [Google Scholar]

- Niyongabo, E.; Gasaba, E.; Niyonsenga, P.; Ndayizeye, M.; Ninezereza, J.B.; Nsabimana, D.; Nshimirimana, A.; Abakundanye, S. Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice regarding Pressure Ulcers Prevention and Treatment. Open J. Nurs. 2022, 12, 316–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halász, B.G.; Bérešová, A.; Tkáčová, Ľ.; Magurová, D.; Lizáková, Ľ. Nurses’ Knowledge and Attitudes towards Prevention of Pressure Ulcers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojastehfar, S.; Ghezeljeh, T.N.; Haghani, S. Factors related to knowledge, attitude, and practice of nurses in intensive care unit in the area of pressure ulcer prevention: A multicenter study. J. Tissue Viability 2020, 29, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogan, S.; Caliskan, N. A Descriptive Study of Turkish Intensive Care Nurses’ Pressure Ulcer Prevention Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceived Barriers to Care. Wound Manag. Prev. 2019, 65, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmazer, T.; Tüzer, H.; ERCİYAS, A. Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Prevention of Pressure Ulcer: Intensive Care Units Sample in Turkey. Turk. Klin. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 11, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.E.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Rothstein, H.R. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, 4th ed.; Biostat, Inc.: Englewood, NJ, USA, 2022; Available online: www.Meta-Analysis.com (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppar, T. Meta-analysis: How to quantify and explain heterogeneity? Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2020, 19, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Waugh, S. Research study: An assessment of registered nurses’ knowledge of pressure ulcers prevention and treatment. Kans. Nurse 2009, 84, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Murugiah, S.; Ramuni, K.; Das, U.; Hassan, H.C.; Abdullah, S.K.B.F. The knowledge of pressure ulcer among nursing students and related factors. Enfermeria Clin. 2020, 30, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat-Johnson, M.; Barnett, C.; Wand, T.; White, K. Knowledge and Attitudes of Nurses Toward Pressure Injury Prevention. J. Wound, Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2018, 45, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, S.; Sönmez, M.; Kısacık, Ö.G. The effect of knowledge levels of intensive care nurses about pressure injuries on their attitude toward preventing pressure injuries. J. Tissue Viability 2023, 32, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) and Year of Publication | 1. Were the Criteria for Inclusion in the Sample Clearly Defined? | 2. Were the Study Objects and the Setting Described in Detail? | 3. Was the Exposure Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | 4. Were Objective, Standard Criteria Used for Measurement of the Condition? | 5. Were Confounding Factors Identified? | 6. Were Strategies to Deal with Confounding Factors Stated? | 7. Were the Outcomes Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | 8. Was an Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? | Total Score | Share of Answers YES | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zencir et al. [40] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/8 | 87.5% | Excellent |

| Şahan & Güler [41] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8/8 | 100% | Excellent |

| Alshahrani et al. [42] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8/8 | 100% | Excellent |

| Zabidi et al. [43] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/8 | 87.5% | Excellent |

| Ghazanfari et al. [30] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8/8 | 100% | Excellent |

| Niyongabo et al. [44] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/8 | 87.5% | Excellent |

| Halász et al. [45] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8/8 | 100% | Excellent |

| Khojastehfar et al. [46] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8/8 | 100% | Excellent |

| Aydoğan & Çalışkan [47] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8/8 | 100% | Excellent |

| Yilmazer et al. [48] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8/8 | 100% | Excellent |

| Author/s, Year of Publication, and Country of Origin | Study Aim/Objective | Method | Instrument Used | Nurse (n) | Key Findings | Limitations | Quality Appraisal Score (JBI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zencir et al. [40] Turkey | To evaluate the knowledge and attitudes of surgical nurses regarding the prevention of pressure injuries | Descriptive and cross-sectional in nature | Pressure Ulcer Prevention Knowledge Assessment Instrument (PUPKAI-T) Attitude Toward Pressure Ulcer Prevention Instrument (APuP) | 203 |

| The findings of the research are primarily derived from the self-reports of the nursing staff. Additionally, the investigation was limited to a single institution, which restricts the generalizability of the results to the broader context of Turkey. Lastly, a pilot study was not performed to assess the feasibility and applicability of the research methodology prior to comprehensive data collection. | 7/8 |

| Şahan & Güler [41] Turkey | To determine nurses’ knowledge levels and attitudes regarding pressure injury (PI) and to reveal the relationship between these two variables | Quantitative, descriptive study | Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Assessment Tool (PUKAT) 2.0 Attitude toward Pressure Ulcer Prevention (APuP) The study did not investigate the practice of preventing pressure injury | 604 |

| This study presents findings that are limited to a single country, which restricts the ability to generalize the results to the broader nursing population. A comparison of the current results with existing literature reveals discrepancies in the overall and subscale scores related to knowledge and attitudes, as well as in the comparison of these two domains and the factors influencing them. These differences may stem from variations in sample sizes and the specific scales employed to assess knowledge and attitudes regarding pressure injury prevention, particularly considering that the PUKAT scale has undergone revisions. Utilizing a unified scale to evaluate nurses’ knowledge and attitudes toward PI could yield more precise and widely generalizable findings. | 8/8 |

| Alshahrani et al. [42] Saudi Arabia | To explore nurses’ knowledge and attitudes toward pressure injury prevention before and after implementing an educational intervention | Pre- and post-intervention study design | Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Assessment Tool (PUKAT 2.0) Attitude toward Pressure Ulcer Prevention (APuP) The practice of pressure injury prevention was not part of this study | Pre-inter-ven-tion phase = 190 Post-inter-ven-tion phase = 195 |

| One notable limitation of the study is the lack of distinct participant codes, which hinders the evaluation of knowledge and attitude changes on an individual basis. This constraint restricts the capacity to analyze the correlation between the intervention and the observed changes. Future research should incorporate strategies to effectively monitor participants throughout the various evaluation stages. Furthermore, the absence of a clear criterion for determining adequate knowledge within the PUKAT2.0 instrument constrained the comprehensiveness of the assessment. | 8/8 |

| Zabidi et al. [43] Saudi Arabia | To assess nurses’ knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) toward pressure injury prevention | Cross-sectional descriptive design | Nurses’ Knowledge of Pressure Ulcer Prevention & Management Questionnaire Nurses’ Attitude of Pressure Ulcer Prevention Questionnaire Nurses’ Practice of Pressure Ulcer Prevention Questionnaire | 243 |

| The limitation is that, although the study identified particular correlations among nurses regarding their KAP related to pressure injury prevention, comparisons with other studies demonstrate some inconsistencies in these associations. This variation emphasizes the necessity for additional research to clarify the intricate relationships in KAP, as well as their combined influence on pressure injury prevention within clinical environments. | 7/8 |

| Ghazanfari et al. [30] Iran | To investigate the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of Iranian ICU nurses related to pressure injury prevention | Quantitative, cross-sectional study | Pieker Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test (PPUKT) Attitude toward Pressure Ulcer Prevention (APUP) Practice of nurses related to pressure injury prevention | 183 |

| The study reported that self-reporting poses a response bias regarding the perceptions of nurses regarding their KAP related to pressure injury prevention. | 8/8 |

| Niyongabo et al. [44] Burundi, Africa | To assess nurses’ knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding pressure injury prevention and treatment | Cross-sectional study design | Researchers developed a self-report questionnaire on the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of pressure injury prevention based on two published clinical practice guidelines: the Pan Pacific Guideline for the Prevention and Management of Pressure Injury (2012) published by the Australian Wound Management Association and the Association for the Advancement of Wound Care (AAWC) Venous | 25 |

| This study exclusively examined the perspectives of nurses and nursing assistants, thereby omitting other healthcare professionals from consideration. Additionally, the investigation was carried out in a single public hospital with a capacity of 187 beds, despite the presence of five public hospitals in the city of Bujumbura in Burundi. | 7/8 |

| Halász et al. [45] Slovakia | To determine the knowledge and attitudes of nurses toward pressure injury prevention and to find relationships and differences among selected variables | Quantitative, exploratory cross-sectional design | Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Assessment Tool (PUKAT) Attitude toward Pressure Ulcer Prevention (APuP) The study did not explore the practice of pressure injury prevention | 225 |

| The limitations of this study were associated with the limited availability of information regarding the incidence of pressure ulcers, which is notably sparse. The responsibility for data collection and reporting lies with the healthcare system, which may be reluctant to disclose information that could reflect poorly on the quality of care provided. Furthermore, the findings of this study indicate a significant lack of knowledge and appropriate attitudes concerning pressure injury prevention. Consequently, this raises concerns about the adequacy of incidence recording and whether the data accurately represent the true situation. | 8/8 |

| Khojastehfar et al. [46] Iran | To investigate knowledge, attitude, and practice of nurses on pressure injury prevention and their related factors | Quantitative, cross-sectional study with correlational design | Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test (PUKT) Attitude toward Pressure Ulcers (APuP) Practice of Pressure Ulcer Prevention | 308 |

| In this study, the PUKT, which was established in 1995, was utilized to evaluate nurses’ understanding of pressure ulcers. Since that period, advancements in research related to pressure ulcers have been made, potentially rendering the instrument less representative of the most current knowledge in the field. Therefore, undertaking a similar investigation is advisable, employing newly developed assessment tools. | 8/8 |

| Aydoğan & Çalışkan [47] Turkey | To identify the level of knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of the barriers encountered in pressure injury prevention () among intensive care unit (ICU) nurses | Quantitative, cross-sectional, correlational design | Pressure Ulcer Prevention Knowledge Assessment Instrument (PUPKAI-T) Attitude Toward Pressure Ulcer Prevention Instrument (APuP) This study did not assess the practice of pressure ulcer prevention; instead, it explored the barriers to pressure ulcer prevention | 390 |

| Due to the high workload in their Intensive Care Units (ICUs), several hospitals in Ankara, Turkey, indicated their inability to participate in the study, resulting in a limitation to six hospitals. Additionally, nurses who were on maternity or sick leave were excluded from the study. Furthermore, neonatal ICUs were not included in the study, as the data collection instruments were deemed inappropriate for that setting. | 8/8 |

| Yilmazer et al. [48] Turkey | To assess the knowledge and attitudes of nurses toward pressure injury prevention in ICUs | Cross-sectional study design | Tool for pressure ulcer information Attitude toward pressure ulcer tool (APuP) | 81 |

| This study was carried out in the ICUs of a single university hospital; therefore, the findings cannot be generalized to all nursing professionals. | 7/8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asiri, M.Y.; Baker, O.G.; Alanazi, H.I.; Alenazy, B.A.; Alghareeb, S.A.; Alghamdi, H.M.; Alamri, S.B.; Almutairi, T.; Alshumrani, H.M.; Alnassar, M. Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices in Pressure Injury Prevention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111220

Asiri MY, Baker OG, Alanazi HI, Alenazy BA, Alghareeb SA, Alghamdi HM, Alamri SB, Almutairi T, Alshumrani HM, Alnassar M. Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices in Pressure Injury Prevention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare. 2025; 13(11):1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111220

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsiri, Mousa Yahya, Omar Ghazi Baker, Homoud Ibrahim Alanazi, Badr Ayed Alenazy, Sahar Abdulkareem Alghareeb, Hani Mohammed Alghamdi, Saeed Bushran Alamri, Turki Almutairi, Hussien Mohammed Alshumrani, and Muhanna Alnassar. 2025. "Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices in Pressure Injury Prevention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Healthcare 13, no. 11: 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111220

APA StyleAsiri, M. Y., Baker, O. G., Alanazi, H. I., Alenazy, B. A., Alghareeb, S. A., Alghamdi, H. M., Alamri, S. B., Almutairi, T., Alshumrani, H. M., & Alnassar, M. (2025). Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices in Pressure Injury Prevention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare, 13(11), 1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111220