Bridging Barriers: Engaging Ethnic Minorities in Cardiovascular Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

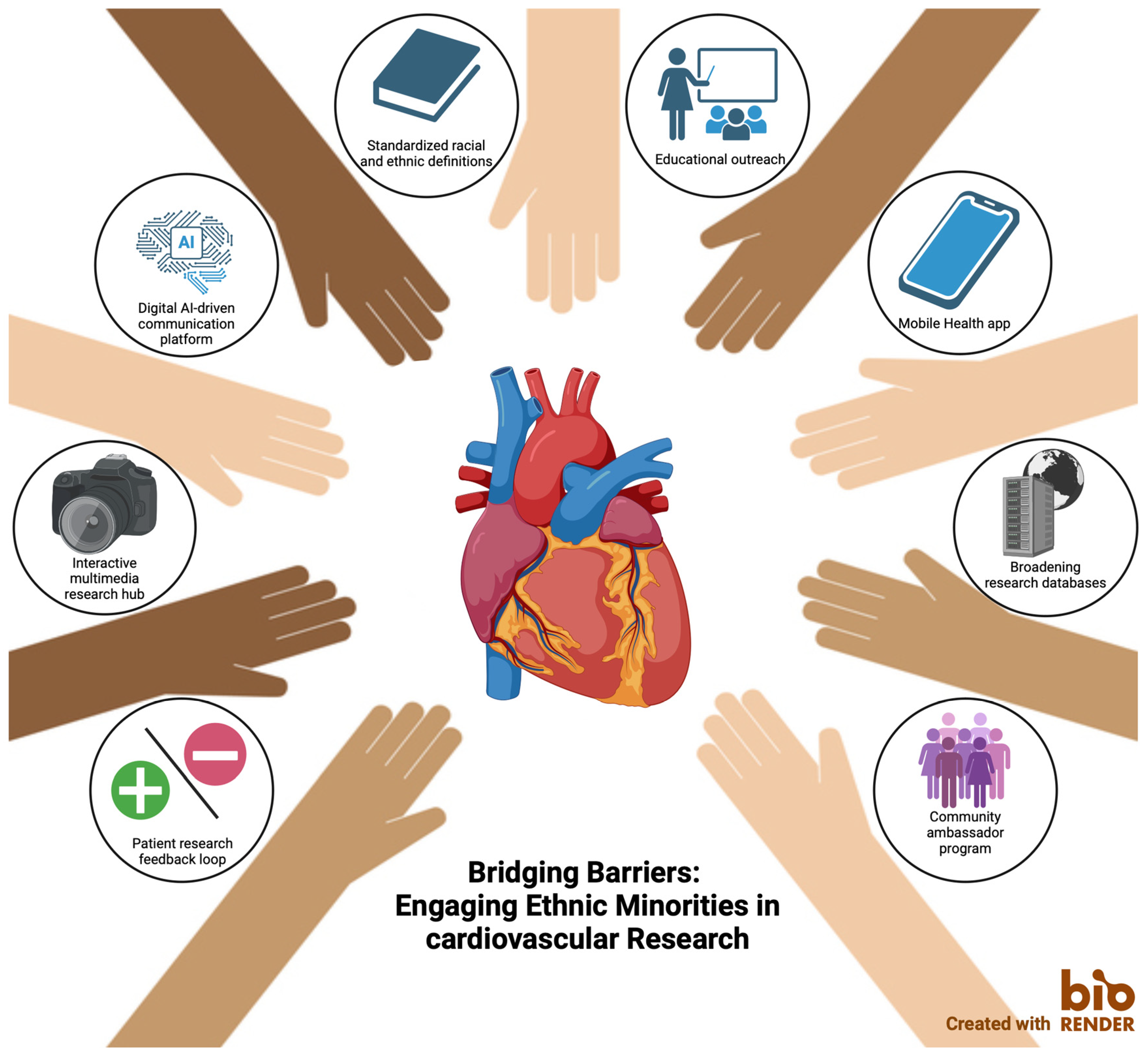

2. Problem Statement

3. Possible Solution Directions

3.1. Educational Outreach

3.2. Interactive Multimedia Information

3.3. Community Ambassadors’ Program

3.4. Registering Ethnicity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Barrier | Proposed Solutions |

|---|---|

| Language barriers | Multilingual communication material |

| AI-powered translation tools | |

| Simplified, linguistically appropriate communication | |

| Healthcare mistrust | Trust-building approach |

| Community ambassadors’ programs | |

| Community involvement in research development | |

| Digital illiteracy | Interactive multimedia tools |

| Interactive consent forms | |

| Mobile health applications | |

| Lack of patient engagement | Feedback systems |

| Gamification for engagement | |

| Cultural sensitivities | Education on cultural beliefs and disease |

| Dietitians offering culturally appropriate nutritional guidance | |

| Cultural competence education for healthcare professionals | |

| Privacy and ethnicity registration concerns | Development of standardized reporting of ethnic background |

| Educating health professionals on the General Data Protection Regulations regarding ethnicity data | |

| Default ethnicity registration |

References

- Dutch Statistics. How Many Residents Have a Foreign Country of Origin? 2024. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/dossier/dossier-asiel-migratie-en-integratie/hoeveel-inwoners-hebben-een-herkomst-buiten-nederland (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Routen, A.; Bodicoat, D.; Willis, A.; Treweek, S.; Paget, S.; Khunti, K. Tackling the lack of diversity in health research. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2022, 72, 444–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.A.; Gutiérrez, D.E.; Frausto, J.M.; Al-Delaimy, W.K. Minority Representation in Clinical Trials in the United States: Trends Over the Past 25 Years. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 264–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Helman, A.; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Why Diverse Representation in Clinical Research Matters and the Current State of Representation within the Clinical Research Ecosystem. In Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underpresented Groups; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Redwood, S.; Gill, P.S. Under-representation of minority ethnic groups in research--call for action. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, 342–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rippe, J.M. Lifestyle Strategies for Risk Factor Reduction, Prevention, and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2019, 13, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, R.; Aatre, R.D.; Kanthi, Y. Diagnostic approach and management of genetic aortopathies. Vasc. Med. 2020, 25, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotseva, K.; de Backer, G.; de Bacquer, D.; Rydén, L.; Hoes, A.; Grobbee, D.; Maggioni, A.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Jennings, C.; Abreu, A.; et al. Lifestyle and impact on cardiovascular risk factor control in coronary patients across 27 countries: Results from the European Society of Cardiology ESC-EORP EUROASPIRE V registry. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, S.; Pravalika, J.; Manjula, P.; Farooq, U. Gender and CVD-Does It Really Matters? Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2023, 48, 101604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacour, N.; Theijse, R.T.; Grewal, S.; Klautz, R.J.M.; Grewal, N. Brief Review: Racial Disparities in the Presentation and Outcomes of Patients with Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms. J. Cardiovascular Dev Dis. 2025, 12, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayne, J.; Garry, J.; Albert, M.A. Brief Review: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Cardiovascular Care with a Focus on Congenital Heart Disease and Precision Medicine. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2023, 25, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, D.; Agyemang, C.; Beune, E.; Meeks, K.; Smeeth, L.; Schulze, M.; Addo, J.; de-Graft Aikins, A.; Galbete, C.; Bahendeka, S.; et al. Migration and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Ghanaian Populations in Europe: The RODAM Study (Research on Obesity and Diabetes Among African Migrants). Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2017, 10, e004013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronks, K.; Snijder, M.B.; Peters, R.J.; Prins, M.; Schene, A.H.; Zwinderman, A.H. Unravelling the impact of ethnicity on health in Europe: The HELIUS study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snijder, M.B.; van Valkengoed, G.M.; Nicolaou, M.; Kunst, A.E.; Peters, R.J.H.; Loyen, A.; Stronks, K. Lifestyle and risk factors for cardiovascular diseases in population groups with different migration backgrounds: Heart & Vascular Statistics. In Cardiovascular Diseases in the Netherlands 2017, Statistics on Lifestyle, Risk Factors, Disease, and Mortality; Dutch Heart Foundation, 2017; Available online: https://www.hartenvaatcijfers.nl/artikelen/leefstijl-en-risicofactoren-voor-hart-en-vaatziekten-in-bevolkingsgroepen-met-verschillende-migratieachtergrond-9cb7d#:~:text=Het%20HELIUS%20onderzoek,-De%20HELIUS%20(Healthy&text=Deelnemers%20hebben%20een%20vragenlijst%20ingevuld,lipidenprofiel%20en%20glucose%20zijn%20gemeten (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Powe, N.R.; Yancy, C. Recalibrating the Use of Race in Medical Research. JAMA 2021, 325, 623–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersha, T.B.; Abebe, T. Self-reported race/ethnicity in the age of genomic research: Its potential impact on understanding health disparities. Hum. Genom. 2015, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Walton, M.; Manias, E.; Walpola, R.L.; Seale, H.; Latanik, M.; Leone, D.; Mears, S.; Harrison, R. The safety of health care for ethnic minority patients: A systematic review. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Duran, N.; Norris, K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e16–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, D.J.; Ding, Y.; Hargreaves, M.; van Ryn, M.; Phelan, S. The association between perceived discrimination and underutilization of needed medical and mental health care in a multi-ethnic community sample. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2008, 19, 894–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L.A.; Beach, M.C.; Johnson, R.L.; Inui, T.S. Delving Below the Surface. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, S21–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.A.; Kalbaugh, C.A. Challenging assumptions about minority participation in US clinical research. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 2217–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getrich, C.M.; Sussman, A.L.; Campbell-Voytal, K.; Tsoh, J.Y.; Williams, R.L.; Brown, A.E.; Potter, M.B.; Spears, W.; Weller, N.; Pascoe, J.; et al. Cultivating a cycle of trust with diverse communities in practice-based research: A report from PRIME Net. Ann. Fam. Med. 2013, 11, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadarzynski, T.; Knights, N.; Husbands, D.; Graham, C.A.; Llewellyn, C.D.; Buchanan, T.; Montgomery, I.; Ridge, D. Achieving health equity through conversational AI: A roadmap for design and implementation of inclusive chatbots in healthcare. PLoS Digit. Health 2024, 3, e0000492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwise, A.K.; Curtis, S.; Diedrich, D.A.; Pickering, B.W. Using artificial intelligence to promote equitable care for inpatients with language barriers and complex medical needs: Clinical stakeholder perspectives. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2024, 31, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.R.; Lawson, C.A.; Wood, A.M.; Khunti, K. Addressing ethnic and global health inequalities in the era of artificial intelligence healthcare models: A call for responsible implementation. J. R. Soc. Med. 2023, 116, 260–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipta, D.A.; Andoko, D.; Theja, A.; Utama, A.V.E.; Hendrik, H.; William, D.G.; Reina, N.; Handoko, M.T.; Lumbuun, N. Culturally sensitive patient-centered healthcare: A focus on health behavior modification in low and middle-income nations-insights from Indonesia. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1353037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woudstra, A.J.; Dekker, E.; Essink-Bot, M.L.; Suurmond, J. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding colorectal cancer screening among ethnic minority groups in the Netherlands-a qualitative study. Health Expect 2016, 19, 1312–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, E. Artificial intelligence and mass personalization of communication content—An ethical and literacy perspective. New Media Soc. 2022, 24, 1258–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, Q. A Review of the Quality and Impact of Mobile Health Apps. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaou, M.; Araviaki, E.; Musikanski, L. eHealth and mHealth Interventions for Ethnic Minority and Historically Underserved Populations in Developed Countries: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Community Well-Being 2020, 3, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agerström, J.; Andréll, C.; Bremer, A.; Strömberg, A.; Årestedt, K.; Israelsson, J. All Else Being Equal: Examining Treatment Bias and Stereotypes Based on Patient Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status With In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Clinical Vignettes. Heart Lung J. Cardiopulm. Acute Care 2024, 63, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, N.; Kaur, A.; Swain, J.; Joseph, J.J.; Brewer, L.C. Community-Based Participatory Research to Improve Cardiovascular Health Among US Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2022, 9, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.A.; Joosten, Y.A.; Wilkins, C.H.; Shibao, C.A. Case Study: Community Engagement and Clinical Trial Success: Outreach to African American Women. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2015, 8, 388–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilla, F. Data Collection in the Field of Ethnicity; European Commission: 2021. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2021-09/data_collection_in_the_field_of_ethnicity.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Ploem, C.; Suurmond, J. Registering ethnicity for covid-19 research: Is the law an obstacle? BMJ 2020, 370, m3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Publishing., J.C.f.A.o.I.a.D.i. Diversity data collection in scholarly publishing. Available online: https://www.rsc.org/policy-evidence-campaigns/inclusion-diversity/joint-commitment-for-action-inclusion-and-diversity-in-publishing/diversity-data-collection-in-scholarly-publishing/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Flanagin, A.; Frey, T.; Christiansen, S.L.; the AMA Manual of Style Committee. Updated Guidance on the Reporting of Race and Ethnicity in Medical and Science Journals. JAMA 2021, 326, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bacour, N.; Grewal, S.; Ploem, M.C.; Suurmond, J.; Klautz, R.J.M.; Grewal, N. Bridging Barriers: Engaging Ethnic Minorities in Cardiovascular Research. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111217

Bacour N, Grewal S, Ploem MC, Suurmond J, Klautz RJM, Grewal N. Bridging Barriers: Engaging Ethnic Minorities in Cardiovascular Research. Healthcare. 2025; 13(11):1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111217

Chicago/Turabian StyleBacour, Nora, Simran Grewal, M. Corrette Ploem, Jeanine Suurmond, Robert J. M. Klautz, and Nimrat Grewal. 2025. "Bridging Barriers: Engaging Ethnic Minorities in Cardiovascular Research" Healthcare 13, no. 11: 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111217

APA StyleBacour, N., Grewal, S., Ploem, M. C., Suurmond, J., Klautz, R. J. M., & Grewal, N. (2025). Bridging Barriers: Engaging Ethnic Minorities in Cardiovascular Research. Healthcare, 13(11), 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111217