Reconciliation of Work and Personal Roles Among Critical Care Nurses: Constructivist Grounded Theory Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Researcher Positioning

2.3. Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Rigor and Trustworthiness

2.7. Ethical Considerations

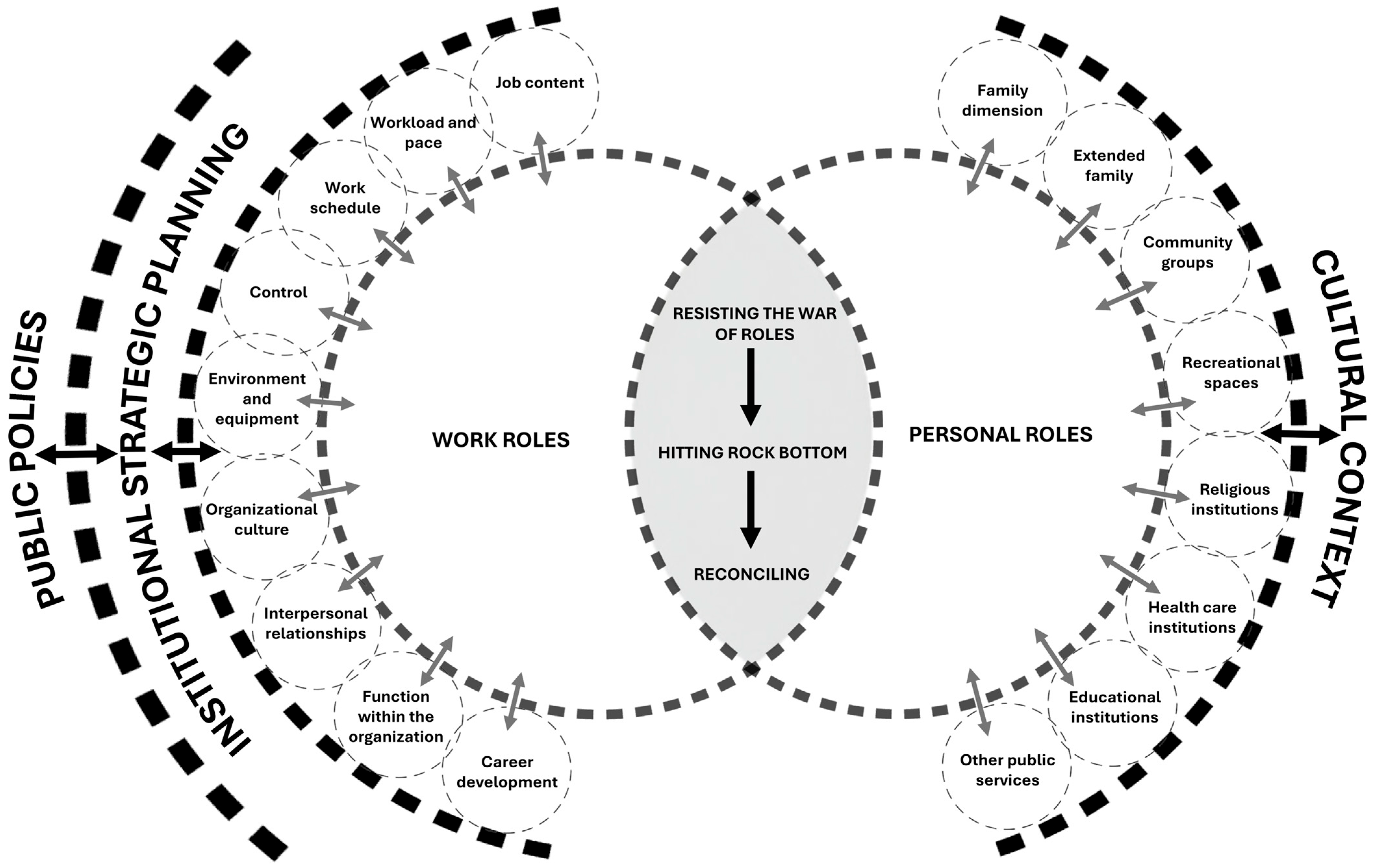

3. Results and Discussion

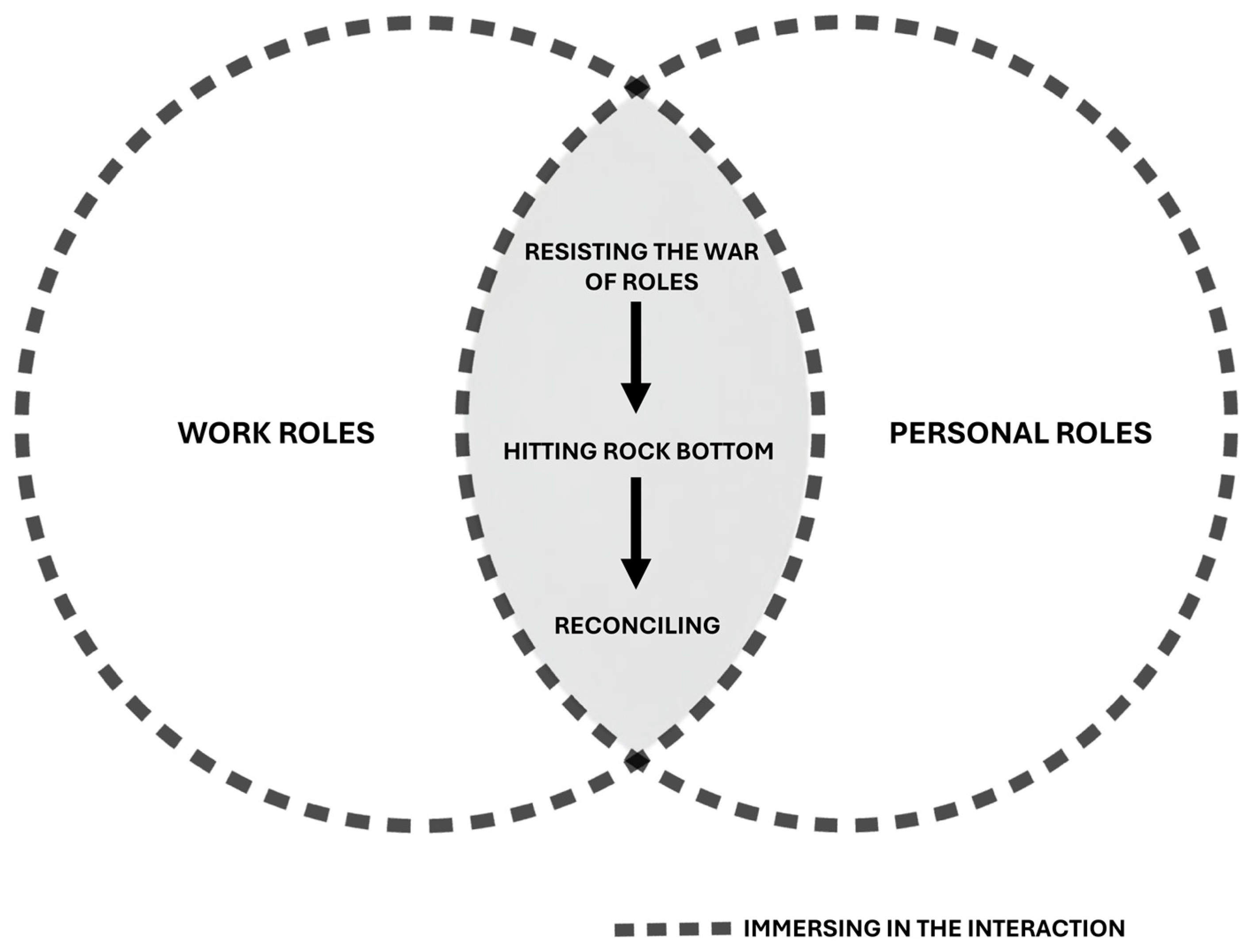

3.1. Immersing in the Interaction

“My female colleagues are constantly on video calls, coordinating lunch, coordinating everything. Like tomorrow—my colleague here—her daughter has to go do sports, and the day after, her son has to go somewhere else. And she’s here, doing her work while coordinating everything with her children”.(Interview, female nurse 29, ICUa, H2)

3.2. Understanding Roles

3.2.1. Work Roles

3.2.2. Personal Roles

3.3. The Process of Reconciling Work and Personal Roles: Resisting the War of Roles

“But you go through a period when you’re more tired—it happened to me at the beginning, when I changed units. I would come home completely exhausted. I think it was everything at once, because there was also emotional fatigue due to the change, new people, and this unit is more challenging, it’s more difficult. I had never worked in the ICU before, and I was assigned to the ICU. During that time, I felt it was harder for me to reconcile work and family life because I was so tired”.(Interview, female nurse 28, ICUa, H2)

“I think that when I first started working… I had a really hard time. I was constantly, um… leaving work feeling bad. I would punish myself for having done something wrong. I also carried it with me, feeling bad deep down, because I wasn’t doing things well, because I was told I wasn’t doing things well. So, yes, I think I definitely carried that with me”.(Interview, female nurse 12, ICUa, H2)

“When you’re new, you’re attentive to everything your boss says, everything your colleagues say. And over time, of course, since you’re new, you’re hyperaware of everything—for example, even on your days off, you’re still thinking about everything that was discussed. Basically, you don’t disconnect from work. It’s typical to be contacted outside of your working hours, and you end up normalizing it — being spoken to about work matters outside your shift”.(Interview, male nurse 15, ICUa, H1)

“We cannot avoid the fact that work affects personal life, and that personal life affects work—these are aspects that are completely interconnected. You will never be able to separate them; both influence and impact each other, for better or worse…”.(Interview, nurse administrator 1, ICUp, H1)

“I believe my father’s example—especially in his work and in his life—was that of a good man. That’s how I would define him: a good man. Good in the sense of being honest. And I think that example is present in my own work, particularly in terms of commitment, honesty, responsibility, and also kindness—not the kind of kindness that tries to please everyone, but the kind that, if there is a chance to do good, then you do it; if you can avoid harming others, then you don’t; to be fair. And regarding my family, my partner plays such an important role, especially because of her ability to reconcile different aspects of life and her strong sense of responsibility. I think the essence I already carried within me has become more organized with her—more structured, more disciplined. And my son… well, he is my driving force. Everything I do, I do think of him. I see him everywhere—I see him in my patients, for example. Before, I might have just been kind and respectful, but since my son was born, I feel I’ve become more affectionate. Not with everyone, but I am more affectionate in that sense, because I’ve learned to express a little more love”.(Interview, male nurse 25, ICUa, H2)

“For example, at the end of the year we organize the premature babies’ celebration… And seeing those little ones who are now big kids—healthy, intact, normal—and laughing like any other child, even though they once weighed, I don’t know, 600 grams… it truly feels like an achievement. For me, it brings a sense of pride, it makes me happy that our work is reflected in the fact that these children are there, playing with their parents and siblings. It feels good to share that with them. I get home, and it’s like I still have that smile on my face—like it’s been imprinted”.(Interview, male nurse 35, ICUp, H1)

Interviewer MVC [Author]: Could you describe a situation in which you believe your personal life influenced your work? Nurse 28: For example, when I separated from my ex-partner—sometimes you just can’t separate things. I remember that shift was awful; I reacted terribly and was very distracted. In the end, I spoke with my supervisor, and I had to leave because I kind of had a breakdown.(Interview, female nurse 28, ICUa, H2)

“It’s horrible—there’s no time, no time at all. We don’t have time. The exhaustion… and that’s one of the reasons why I still don’t have children, because I don’t know how I would divide my time”.(Interview, female nurse 33, ICUp, H1)

“Because she comes home tired, I see it—her face, the dark circles under her eyes. She doesn’t want to do anything. She comes in, throws herself on the bed, takes off her clothes and leaves them on the floor… she’s unmotivated. You can tell—she doesn’t want to talk, doesn’t want to engage in conversation. She just wants to sit and watch TV or her shows, with no interaction. That’s when I say, ‘Alright, it was a rough shift.’ Then I ask her how it went, and that’s when she tells me”.(Interview, nurse’s family member 4)

3.4. The Process of Reconciling Work and Personal Roles: Hitting Rock Bottom

“I had a crying episode, right there at the table while having lunch with my family, with a family member sitting next to me looking at me as if to say, ‘what’s wrong with you?’ And when I saw her, I thought: no, I can’t keep wasting time thinking about what is happening at work and wasting this valuable and limited time I have with my family. I feel that was the trigger, so to speak. It cannot be that I stop enjoying the moment because of what work might cause me. At that point, it became clear that I had to do something. In fact, that same day I started looking and researching which psychologist I could go to…”.(Interview, nurse administrator 7, ICUp, H1)

“I believe that, driven by anxiety, I hit rock bottom at some point. I would suddenly find myself sitting and thinking, ‘Why do I feel so anxious if I have nothing tomorrow?’ For instance, tomorrow is Saturday, there’s nothing scheduled. And yet I would feel that weight on my chest, palpitations, and everything. I would ask myself, ‘What is going on? I’m at home, doing nothing, just quietly watching a movie.’ It was like—I can’t live like this anymore. So I went to a psychiatrist, a psychologist, the whole thing. They put me on medication, but nothing changed. Then I realized that when I started working, I had stopped exercising. Exercise used to be a habit for me, a family habit. So I had abandoned it, and it actually coincided a bit with the onset of these symptoms… That’s when I said, ‘Alright, I need to make a change. I want to do something.’ Honestly, the pillar for me is my family”.(Interview, female nurse 4, ICUa, H1)

3.5. The Process of Reconciling Work and Personal Roles: Reconciling

“The difference lies in the experience you have in the job—it allows you, in a way, to discern what is truly important from what might not be so important, to recognize what holds value and what is more routine. In that sense, of course, each person has their own perspective, but ultimately, there are things that only time and experience enable you to see clearly and to take a certain distance—to decide what deserves your attention, your time, and your energy. I mean, where you choose to place emphasis”.(Interview, female nurse 10, ICUa, H2)

“One learns to prioritize in these units because you’re always walking on the edge, on the edge, on… on the brink of the abyss—between whether they live or die. As nurses who work in critical care, we have a significant dose of resilience; we recover from one case after another, from one after another…”.(Interview, nurse administrator 2, ICUa, H2)

“But there comes a moment when you realize that it does take a toll—that it is not necessary to be empathetic to the point of actually feeling the other person’s emotions. You have to be empathetic, yes, but there must be a boundary. And that boundary… you’re not born knowing where it is. That’s where professionals who are trained in these matters can help us. I came to understand this after having worked for about ten years. I wish I had discovered it earlier, because after that, it was as if my mind said, ‘You’ve discovered that psychologists exist…’”.(Interview, male nurse 32, ICUa, H1)

4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

References

- Joint ILO-WHO Committee. Psychosocial Factors at Work: Recognition and Control; ILO/WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pujol-Cols, L.; Lazzaro-Salazar, M. Ten Years of Research on Psychosocial Risks, Health, and Performance in Latin America: A comprehensive Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2021, 37, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zedeck, S.; Mosier, K.L. Work in the family and employing organization. Am. Psychol. 1990, 45, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesga Rodríguez, J.J. La interacción trabajo-familia en el contexto actual del mundo del trabajo. Equidad Desarro. 2019, 1, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. C156—Convention concerning Workers with Family Responsibilities (No. 156); International Labour Organization, 1981. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C156 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- ILO. Ratification of the C156—Convention Concerning Workers with Family Responsibilities, 1981 (No. 156); International Labour Organization, 1983. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:11300:0::NO:11300:P11300_INSTRUMENT_ID:312301 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- SUSESO. Riesgo Psicosocial Laboral en Chile: Resultados de la Aplicación del Cuestionario de Evaluación del Ambiente Laboral y Salud Mental 2023 CEAL-SM/SUSESO; SUSESO: Santiago, Chile, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ekici, D.; Gurhan, N.; Mert, T.; Hizli, I. Effects of Work to Family Conflicts on Services and Individuals in Healthcare Professionals. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2020, 13, 1355. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, J. “Una cuestión de entrega”: Desigualdades de género y factores de riesgo psicosocial en el trabajo de enfermería. Soc. Cult. 2019, 22, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. State of the World’s Nursing 2020: Investing in Education, Jobs and Leadership; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rendón-Díaz, C.; Vargas-Bertancourt, M. El precio de la vocación en el personal de enfermería y su familia. Rev. Cub. Enferm. 2019, 35, e1998. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.H.; Simonetti, M.; Sloane, D.M.; Cerón, C.; Soto, P.; Bravo, D.; Galiano, A.; Behrman, J.R.; Smith, H.L.; McHugh, M.D.; et al. Hospital nurse staffing and patient outcomes in Chile: A multilevel cross-sectional study. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e1145-53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, M.; Riedel, P.; Galiano, A.; Echeverría, A.; Cerón, C. Dotaciones de enfermeras, complejidad de camas, y complejidad de pacientes en hospitales públicos de Chile. Rev. Méd. Chile 2025, 153, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rony, M.K.K.; Numan, S.M.; Alamgir, H.M. The association between work-life imbalance, employees’ unhappiness, work’s impact on family, and family impacts on work among nurses: A cross-sectional study. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2023, 38, 101226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Tao, H.; Ellenbecker, C.H.; Liu, X. Job satisfaction in mainland China: Comparing critical care nurses and general ward nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 1725–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlfort, N.; Cécire, P.; Koestner, R.; Verner-Filion, J. Managing the work-home interface by making sacrifices: Costs of sacrificing psychological needs. Motiv. Emot. 2022, 46, 658–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukasczik, M.; Ahnert, J.; Ströbl, V.; Vogel, H.; Donath, C.; Enger, I.; Gräßel, E.; Heyelmann, L.; Lux, H.; Maurer, J.; et al. Vereinbarkeit von Familie und Beruf bei Beschäftigten im Gesundheitswesen als Handlungsfeld der Versorgungsforschung. Gesundheitswesen 2018, 80, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Contrera, M.; Rivera-Rojas, F.; Febré, N. Psychosocial risks at work: A growing problem with theoretical ambiguities. Salud Cienc. Tecnol. 2024, 4, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eynde, A.; Claessens, E.; Mortelmans, D. The consequences of work-family conflict in families on the behavior of the child. J. Fam. Res. 2020, 32, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, B.; Yildiz, H.; Ayaz Arda, O. Relationship between work–family conflict and turnover intention in nurses: A meta-analytic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3317–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.; Rai, S. Conceptualizing work-life integration: A review and research agenda. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2024, 29, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Contrera, M.; Rivera-Rojas, F.; Villa-Velásquez, J.; Cancino-Jiménez, D.; Vallejos-Vergara, S.; Febré, N. Scoping Review on Ethical Considerations in Research on the Work–Family Interaction Process. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Aldine Transaction: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructivist grounded theory. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 299–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory. A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Contrera, M.; Avilés, L.; Febré, N. Theorizing the Work-Family Interaction Process in Nurses in Intensive Care Units: A Constructivist Grounded Theory Research Protocol. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2025, 24, 16094069251333883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mella, P.F.O.; Narváez, C.G. Análisis del sistema de salud chileno y su estructura en la participación social. Saude Debate 2022, 46, 94–106. [Google Scholar]

- Farías, L. La observación como herramienta de conocimiento y de intervención. In Técnicas y Estrategias en la Investigación Cualitativa; Universidad Nacional de La Plata: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2016; pp. 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Trujillo, N. La Investigación Cualitativa. Una Mirada Desde las Ciencias Sociales y Humanas; Universidad de La Guajira: Riohacha, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval Casilimas, C. Investigación Cualitativa; ARFO: Bogotá, Colombia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry General Secretariat of the Presidency. Decree No. 100. Establishes the Consolidated, Coordinated, and Systematized Text of the Political Constitution of the Republic of Chile; Library of the National Congress of Chile: Valparaíso, Chile, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Labor Directorate. Decree with Force of Law No. 1. Establishes the Consolidated, Coordinated, and Systematized Text of the Labor Code; Labor Directorate: Santiago, Chile, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Public Health. Decree with the Force of Law No. 725; Library of the National Congress of Chile: Valparaíso, Chile, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Institute. Guidelines for the Management of Psychosocial Risks at Work: Work-Life Balance; Ministry of Health, Institute of Public Health: Santiago, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Belgrave, L.; Seide, K. Coding for Grounded Theory. In Current Developments in Grounded Theory; Bryant, A., Charmaz, K., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 167–185. [Google Scholar]

- Nathaniel, A. The logic and language of classic grounded theory: Induction, abduction, and deduction. Grounded Theory Rev. 2023, 22, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K.; Thornberg, R. The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.; Clark, L. The nuances of grounded theory sampling and the pivotal role of theoretical sampling. In Current Developments in Grounded Theory; Bryant, A., Charmaz, K., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 145–166. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, K. Writing grounded theory. In Grounded Theory in Management Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D.; Beck, C. Essentials of Nursing Research. Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice, 9th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Bases de la Investigación Cualitativa. Técnicas y Procedimientos para Desarrollar la Teoría Fundamentada, 1st ed.; Editorial Universidad de Antioquia: Medellín, Colombia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B. Theoretical Sensitivity; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S.C. Work/Family Border Theory: A New Theory of Work/Family Balance. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of Conflict between Work and Family Roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenblatt, E. Work/Life Balance: Wisdom or Whining. Organ. Dyn. 2002, 31, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, S.A.E.; Kompier, M.A.; Roxburgh, S.; Houtman, I.L. Does Work–Home Interference mediate the relationship between workload and well-being? J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 532–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, S.A.E.; Taris, T.W.; Kompier, M.A.J.; Dikkers, J.S.E.; Van Hooff, M.L.M.; Kinnunen, U.M. Work-home interaction from a work psychological perspective: Development and validation of a new questionnaire, the SWING. Work Stress 2005, 19, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, J.H.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M. Work–family facilitation: A theoretical explanation and model of primary antecedents and consequences. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2007, 17, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, G.; McCarthy, A.M. Work-life integration: Experiences of mid-career professional working mothers. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 599–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, B. Glossary of Key Terms and Concepts. In Role Theory; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1979; pp. 381–397. [Google Scholar]

- Albizu Gallastegi, E.; Landeta Rodríguez, J. Dirección estratégica de los recursos humanos. In Teoría y Práctica, 2nd ed.; Ediciones Piramide: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Neffa, J.C. ¿Qué son los Riesgos Psicosociales en el Trabajo?: Reflexiones a Partir de una Investigación Sobre el Sufrimiento en el Trabajo Emocional y de Cuidado; Centro de Estudios e Investigaciones Laborales: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Georgas, J. Family and Culture. In Encyclopedia of Applied Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen, K.F.; Hansen, B.S.; Wøien, H.; Tønnessen, S. The core qualities and competencies of the intensive and critical care nurse, a meta-ethnography. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 4693–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, P. From novice to expert. Am. J. Nurs. 1982, 82, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cottingham, M.D.; Chapman, J.J.; Erickson, R.J. The Constant Caregiver: Work–Family Spillover among Men and Women in Nursing. Work Employ. Soc. 2020, 34, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öke Karakaya, P.; Sönmez, S.; Aşık, E. A phenomenological study of nurses’ experiences with maternal guilt in Turkey. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 2515–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, B. The Concise ProQOL Manual, 2nd ed.; ProQOL.org: Pocatello, ID, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm, B. Measuring compassion satisfaction as well as fatigue: Developmental history of the Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue Test. In Treating Compassion Fatigue; Figley, C.R., Ed.; Brunner-Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, N.; Elton, J.; Auer, J.; Pocock, B. Understanding and managing work-life interaction across the life course: A qualitative study. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2014, 52, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, T.K.; Matthews, M.J.; Bolino, M.C.; Gabriel, A.S.; Ganster, M.L. Understanding the Relationships Between Divorce and Work: A Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2025, 51, 427–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çam, O.; Büyükbayram, A. The Results of Nurses’ Increasing Emotional Intelligence and Resilience. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2015, 6, 130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Jakimowicz, S.; Perry, L.; Lewis, J. Compassion satisfaction and fatigue: A cross-sectional survey of Australian intensive care nurses. Aust. Crit. Care 2018, 31, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawar, L.N.; Radovich, P.; Valdez, R.M.; Zuniga, S.; Rondinelli, J. Compassion Fatigue and Compassion Satisfaction Among Multisite Multisystem Nurses. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2019, 43, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unjai, S.; Forster, E.M.; Mitchell, A.E.; Creedy, D.K. Predictors of compassion satisfaction among healthcare professionals working in intensive care units: A cross-sectional study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2023, 79, 103509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Majid, S.; Carlson, N.; Kiyohara, M.; Faith, M.; Rakovski, C. Assessing the Degree of Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue Among Critical Care, Oncology, and Charge Nurses. J. Nurs. Adm. 2018, 48, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clinical Nurses (n = 38) | Nurse Administrators (n = 8) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 10 | 0 |

| Female | 28 | 8 |

| Age | ||

| 25–30 | 4 | 0 |

| 31–40 | 24 | 3 |

| 41–50 | 8 | 2 |

| 51–65 | 2 | 3 |

| Unit * | ||

| Intensive Care Units, adult (ICUa) | 32 | 6 |

| Intensive Care Units, pediatric/neonatal (ICUp) | 6 | 2 |

| Children/Dependents Under Their Care | ||

| No | 22 | 4 |

| Yes | 16 | 4 |

| Work Experience (years) | ||

| 1–10 | 13 | 1 |

| 11–20 | 22 | 4 |

| 21–30 | 2 | 2 |

| 31–50 | 1 | 1 |

| Experience in Current Position (years) | ||

| 1–10 | 31 | 1 |

| 11–20 | 6 | 7 |

| 21–30 | 1 | 0 |

| Demographic Data | n |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 3 |

| Female | 2 |

| Age | |

| 18–30 | 1 |

| 31–40 | 3 |

| 41–50 | 1 |

| Occupation | |

| Worker | 4 |

| Student | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valencia-Contrera, M.; Avilés, L.; Febré, N. Reconciliation of Work and Personal Roles Among Critical Care Nurses: Constructivist Grounded Theory Research. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101206

Valencia-Contrera M, Avilés L, Febré N. Reconciliation of Work and Personal Roles Among Critical Care Nurses: Constructivist Grounded Theory Research. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101206

Chicago/Turabian StyleValencia-Contrera, Miguel, Lissette Avilés, and Naldy Febré. 2025. "Reconciliation of Work and Personal Roles Among Critical Care Nurses: Constructivist Grounded Theory Research" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101206

APA StyleValencia-Contrera, M., Avilés, L., & Febré, N. (2025). Reconciliation of Work and Personal Roles Among Critical Care Nurses: Constructivist Grounded Theory Research. Healthcare, 13(10), 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101206