Are We Going to Give Up Imaging in Cryptorchidism Management?

Abstract

1. Introduction

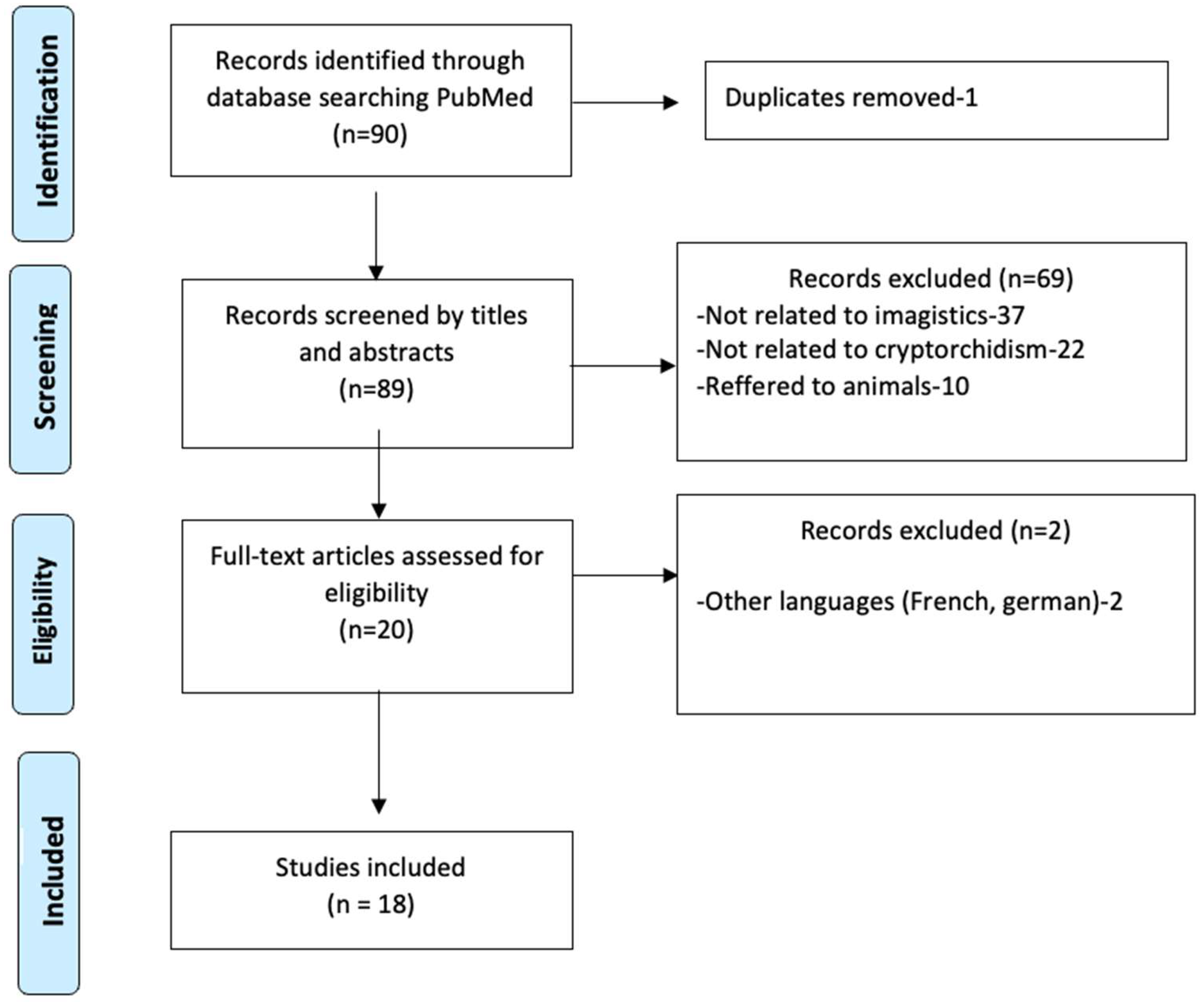

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. The Role of Ultrasonography in UDT Management

3.2. The Role of CT in the Management of Undescended Testes

3.3. The Role of MRI in the Management of Undescended Testes

| Study | No. of Patients | No. of Non-Palpable Testes | No. of True Positive Testes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fritzsche P.J. et al. [21] | 32 | 16 | 15 |

| Kier R. et al. [22] | 24 | 8 | 5 |

| Miyano T. et al. [23] | 17 | 11 | 9 |

| Sarihan H. et al. [24] | 20 | 17 | 13 |

| Siemer S. et al. [25] | 29 | 29 | 21 |

3.4. The Role of Laparoscopy in the Management of Undescended Testes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leslie, S.W.; Sajjad, H.; Villanueva, C.A. Cryptorchidism. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gnech, M.; van Uitert, A.; Kennedy, U.; Skott, M.; Zachou, A.; Burgu, B.; Castagnetti, M.; Hoen, L.; O’Kelly, F.; Quaedackers, J.; et al. European Association of Urology/European Society for Paediatric Urology Guidelines on Paediatric Urology: Summary of the 2024 Updates. Eur. Urol. 2024, 86, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, L.H.; Lorenzo, A.J. Cryptorchidism: A practical review for all community healthcare providers. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2017, 11, S26–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubert, O.; Zaidan, H.; Garnier, H.; Saxena, A.K.; Cascio, S. European Paediatric Surgeons’ Association Survey on the Adherence to EAU/ESPU Guidelines in the Management of Undescended Testes. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2024, 34, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, R.L.; Shelton, J.; Diefenbach, K.A.; Arnold, M.; Peter, S.D.S.; Renaud, E.J.; Slidell, M.B.; Sømme, S.; Valusek, P.; Villalona, G.A.; et al. Management of the undescended testis in children: An American pediatric surgical association outcomes and evidence-based practice committee systematic review. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 57, 1293–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, B.H.; Olawoyin, O.; Arlen, A.M.; Silva, C.T.; Weiss, R.M. Is there a role for ultrasound in management of the non-palpable testicle? J. Pediatr. Urol. 2024, 20, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreyas, K.; Rathod, K.J.; Sinha, A. Management of high inguinal undescended testis: A review of literature. Ann. Pediatr. Surg. 2021, 17, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, G.E.; Patel, B.; McBride, C.A. Pre-referral ultrasound for cryptorchidism: Still common, still not necessary. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2024, 60, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesanya, O.A.; Ademuyiwa, A.O.; Evbuomwan, O.; Adeyomoye, A.A.; Bode, C.O. Preoperative localization of undescended testes in children: Comparison of clinical examination and ultrasonography. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2014, 10, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.P.; Van Heukelom, J. Torsion of an undescended testis located in the inguinal canal. J. Emerg. Med. 2012, 42, 538–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullendorff, C.M.; Hederström, E.; Forsberg, L. Preoperative ultrasonography of the undescended testis. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 2015, 19, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, J.S. Surgical management of the undescended testis: Recent advances and controversies. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2016, 26, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartigan, S.; Tasian, G.E. Unnecessary diagnostic imaging: A review of the literature on preoperative imaging for boys with undescended testes. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2014, 3, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tasian, G.E.; Copp, H.L.; Baskin, L.S. Diagnostic imaging in cryptorchidism: Utility, indications, and effectiveness. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011, 46, 2406–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, D.; Tasian, G. Current Management of Undescended Testes. Curr. Treat. Options Pediatr. 2016, 2, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Yang, H.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Zhangk, J.; Wang, A.; Lai, X.H.; Qiu, Y. Single scrotal incision orchiopexy versus the inguinal approach in children with palpable undescended testis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2016, 32, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Bindman, R.; Lipson, J.; Marcus, R.; Kim, K.P.; Mahesh, M.; Gould, R.; de González, A.B.; Miglioretti, D.L. Radiation dose associated with common computed tomography examinations and the associated lifetime attributable risk of cancer. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 2078–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnaswami, S.; Fonnesbeck, C.; Penson, D.; McPheeters, M.L. Magnetic resonance imaging for locating nonpalpable undescended testicles: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1908–e1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanemoto, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Kojima, Y.; Maruyama, T.; Ito, M.; Kohri, K. Accuracy of ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of non-palpable testis. Int. J. Urol. 2005, 12, 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emad-Eldin, S.; Abo-Elnagaa, N.; Hanna, S.A.; Abdel-Satar, A.H. The diagnostic utility of combined diffusion-weighted imaging and conventional magnetic resonance imaging for detection and localization of non palpable undescended testes. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2016, 60, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzsche, P.J.; Hricak, H.; Kogan, B.A.; Winkler, M.L.; Tanagho, E.A. Undescended testis: Value of MR imaging. Radiology 1987, 164, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kier, R.; McCarthy, S.; Rosenfield, A.T.; Rosenfield, N.S.; Rapoport, S.; Weiss, R.M. Nonpalpable testes in young boys: Evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology 1988, 169, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyano, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Shimomura, H.; Tomita, T. Magnetic resonance imaging for localizing the nonpalpable undescended testis. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1991, 26, 607–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarihan, H.; Sari, A.; Abeş, M.; Dinç, H. Nonpalpable undescended testis: Value of magnetic resonance imaging. Minerva Urol. Nefrol. 1998, 50, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siemer, S.; Humke, U.; Uder, M.; Hildebrandt, U.; Karadiakos, N.; Ziegler, M. Diagnosis of nonpalpable testes in childhood: Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and laparoscopy in a prospective study. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2000, 10, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaira, K.; Zubair, M.; Mehmood, S.; Dab, R.H. Ultrasound, CT-Scan, and Laparoscopy; Diagnostic Observations on Non-Palpable Testis. Prof. Med. J. 2008, 15, 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Li, S.; Yin, J.; Bao, J.; Zeng, H.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Xing, Z.; Zhao, W.; Liu, C.; et al. A prediction model for risk factors of testicular atrophy after orchiopexy in children with undescended testis. Transl. Pediatr. 2021, 10, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Ortiz, J.; Muã±Iz-Colon, L.; Escudero, K.; Perez-Brayfield, M. Laparoscopy in the surgical management of the non-palpable testis. Front. Pediatr. 2014, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saylors, S.; Oyetunji, T.A. Management of undescended testis. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2024, 36, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, H.; Kogan, B.A. The role of laparoscopy in children with groin problems. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2014, 3, 418–428. [Google Scholar]

- Salah, S.E.E.; Ahmed, E.O.E. The role of laparoscopy in non-palpable undescended testicle: Analysis and review of the experience from two cities in Sudan. Afr. J. Paediatr. Surg. 2022, 19, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snodgrass, W.; Bush, N.; Holzer, M.; Zhang, S. Current referral patterns and means to improve accuracy in diagnosis of undescended testis. Pediatrics 2011, 127, e382–e388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gavrilovici, C.; Laptoiu, A.-R.; Ciongradi, C.-I.; Pirtica, P.; Spoiala, E.-L.; Hanganu, E.; Pirvan, A.; Glass, M. Are We Going to Give Up Imaging in Cryptorchidism Management? Healthcare 2025, 13, 1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101192

Gavrilovici C, Laptoiu A-R, Ciongradi C-I, Pirtica P, Spoiala E-L, Hanganu E, Pirvan A, Glass M. Are We Going to Give Up Imaging in Cryptorchidism Management? Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101192

Chicago/Turabian StyleGavrilovici, Cristina, Alma-Raluca Laptoiu, Carmen-Iulia Ciongradi, Petronela Pirtica, Elena-Lia Spoiala, Elena Hanganu, Alexandru Pirvan, and Monika Glass. 2025. "Are We Going to Give Up Imaging in Cryptorchidism Management?" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101192

APA StyleGavrilovici, C., Laptoiu, A.-R., Ciongradi, C.-I., Pirtica, P., Spoiala, E.-L., Hanganu, E., Pirvan, A., & Glass, M. (2025). Are We Going to Give Up Imaging in Cryptorchidism Management? Healthcare, 13(10), 1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101192