Effectiveness of New Reactivation Approaches in Integrated Long-Term Care—Contribution to the Long-Term Care Act

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Longevity, Which Requires Greater Care for the Elderly Population

1.2. The European Union’s Response to the Phenomenon of Rapid Population Aging

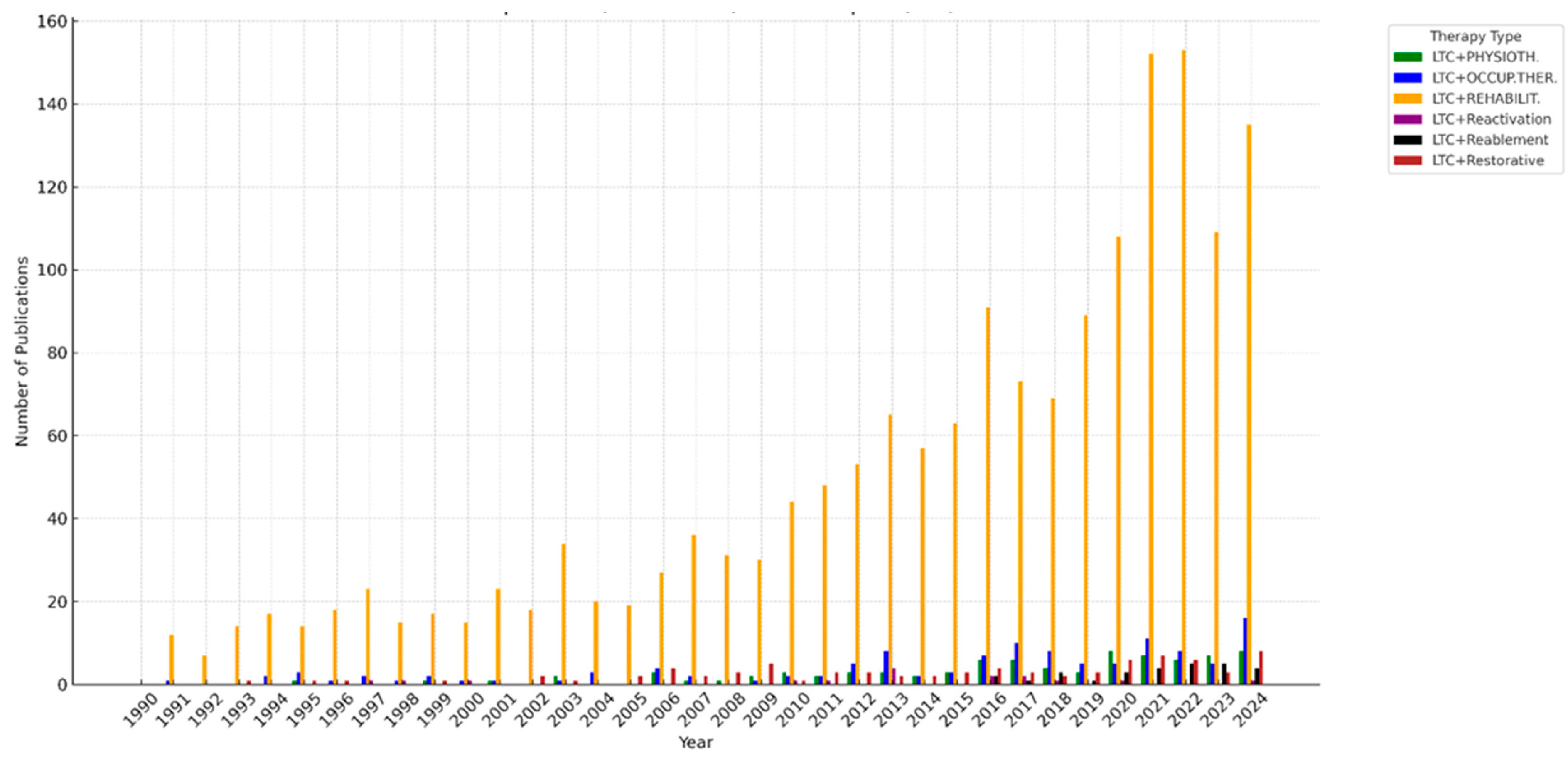

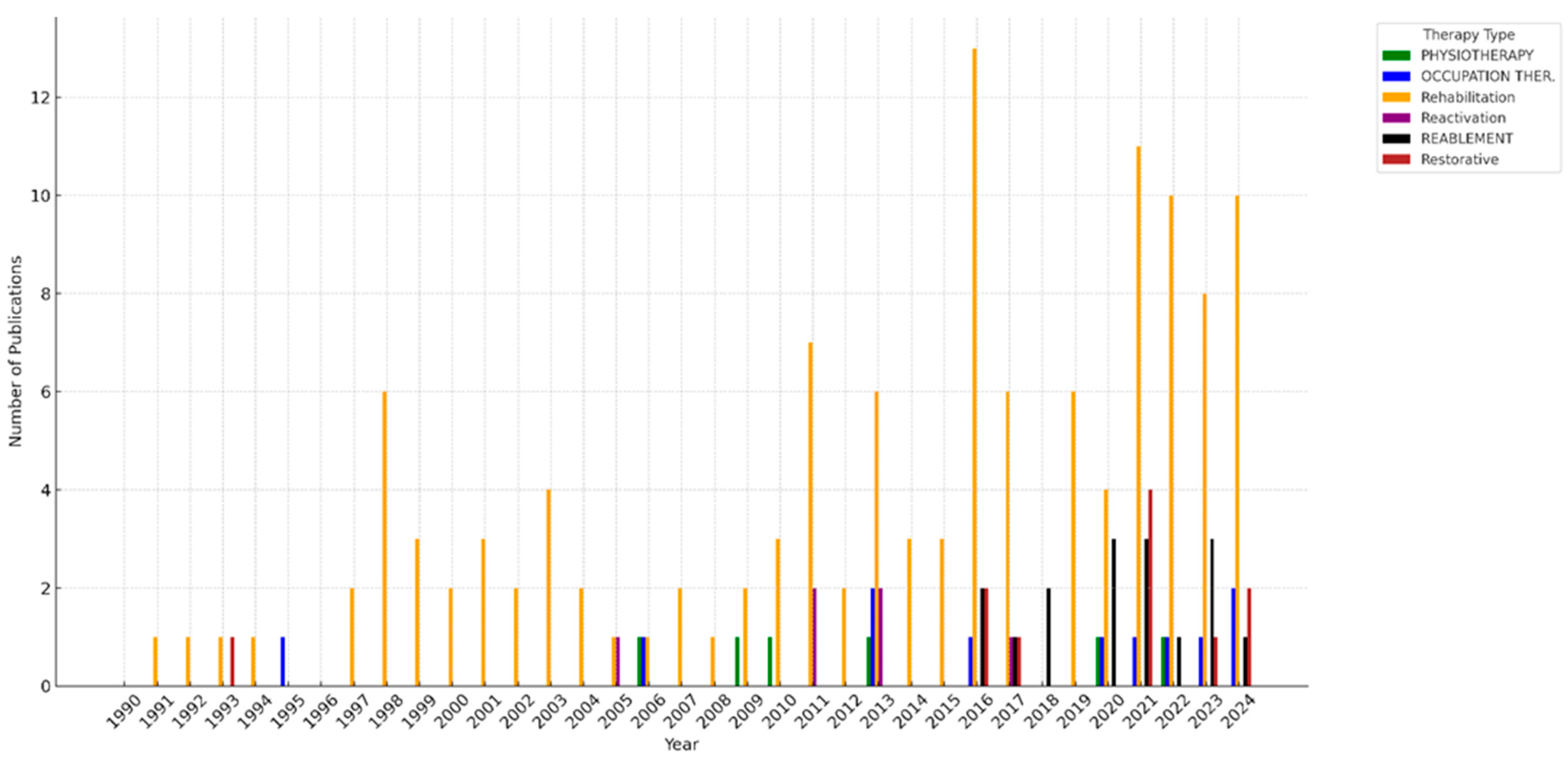

2. Literature Review

2.1. On the Effectiveness of Innovative Approaches to Long-Term Care

2.2. Selected Integrated LTC Services Described in the Literature Review

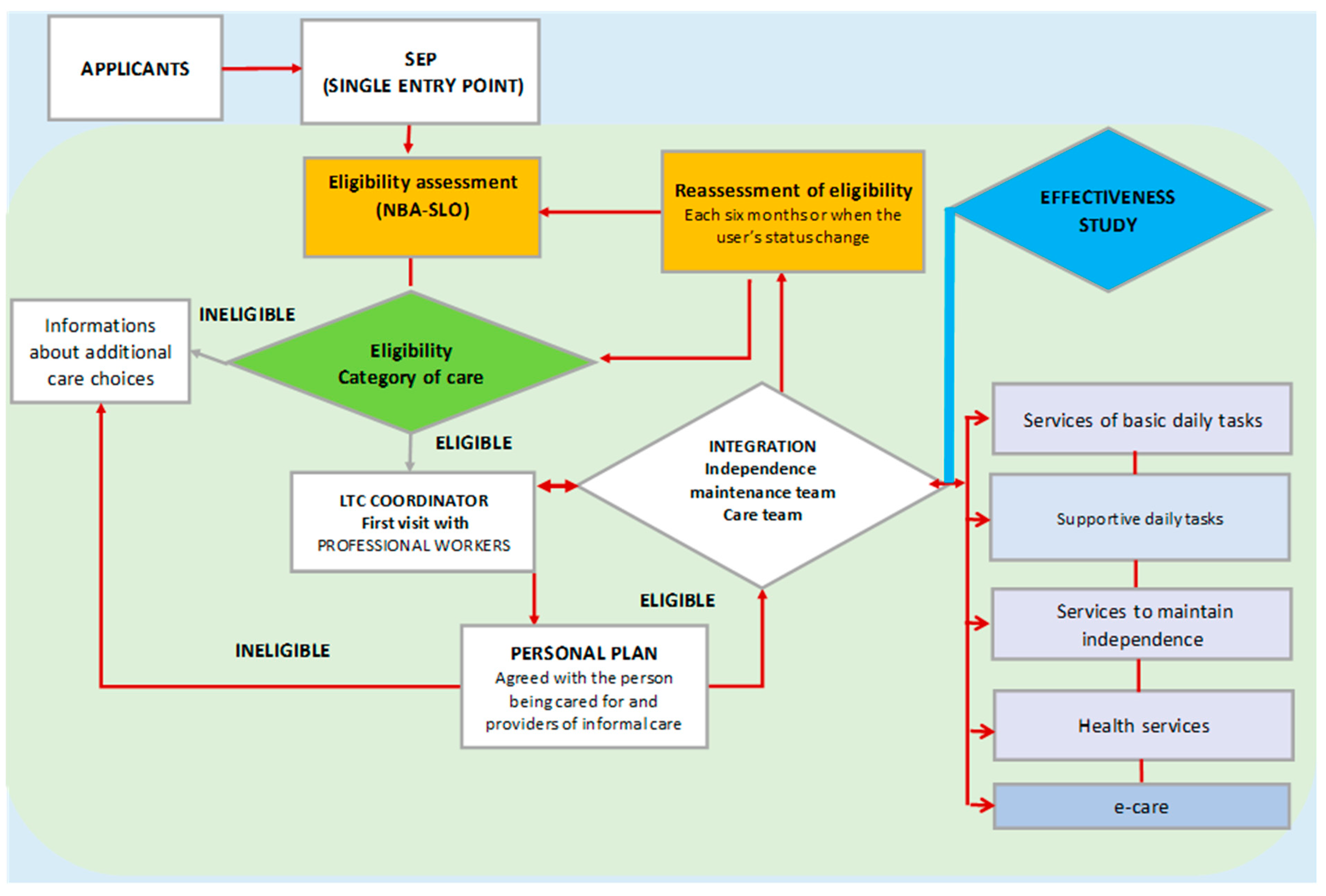

3. Methods and Models Supporting the Long-Term Care Act

3.1. The Long-Term Care Act

3.2. Study Design

3.2.1. MOST Project as an Innovative Approach to the LTC

3.2.2. NBA Assessment Tools and Differences Introduced in the Slovenian LTC Act

- -

- Act on the Social Protection of Mentally and Physically Disabled Persons [57];

- -

- Health Care and Health Insurance Act [58];

- -

- War Veterans Act [59];

- -

- War Disabled Persons Act [60];

- -

- Acts on Social Benefits and Social Welfare Services [61];

- -

- Financial Social Assistance Act [62];

- -

- Exercise of Rights to Public Funds Act [63];

- -

- Pension and Disability Insurance Act [64];

- -

- Parental Care and Family Benefits Act [65].

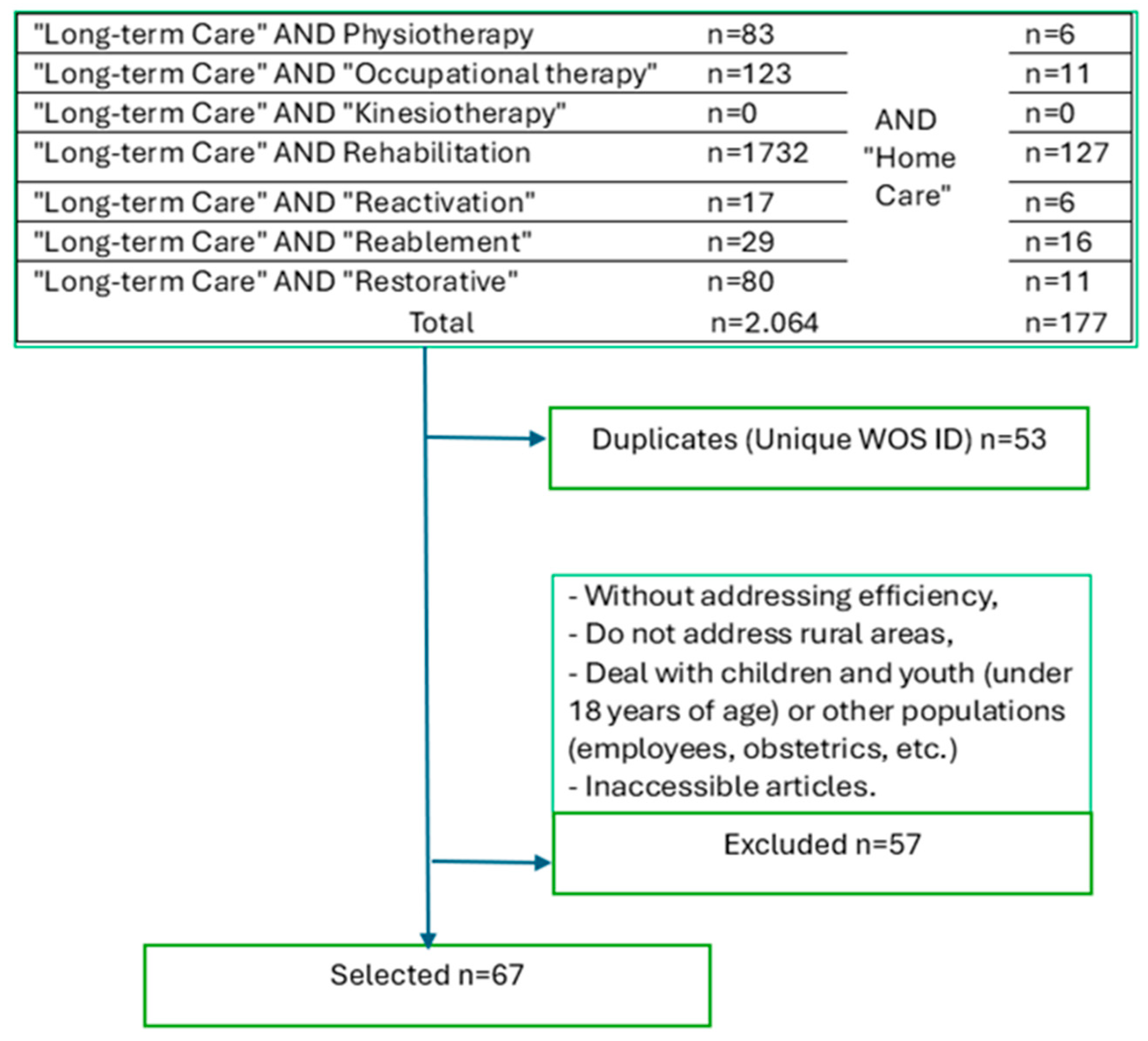

3.3. Determining the Sample for This Paper

3.4. Statistical Analysis

3.4.1. Participant Selection

- -

- A total of 132 home care beneficiaries who consented to integrated care were chosen in the random sample.

- -

- Furthermore, 57 eligible individuals, with a mean age of 79.8 years, who declined this novel therapy, were selected as a control group.

3.4.2. Intervention Details and Assessment Tools

4. Statistics and Findings

4.1. The Values of Parameters of the Proposed Integrated Care Services

4.2. Disparities Between the Suggested Integrated Care Services’ Parameters and Those of Previous Methods

4.3. Testing the Differences Between Results of the Old and New Approaches Only About Services to Maintain Independence

5. Discussion

- For all abilities but M2, the users’ M1-M8 abilities are improved by the MOST approach to LTC at home, including reactivation services, with p < 0.025. Table 6 indicates that M1—Ability to move in the home environment—facilitates mobility for HC users within their housing unit, and M7—Ability to be active outside the home environment—was the most successful. More than 17% of beneficiaries will improve their abilities and reduce their care category, while M2—Cognitive and communication skills—were not much improved. With a probability exceeding 0.975, the reader can assume that Module M2, on cognitive and communication skills, is the sole module where the probability of success may be zero.

- Comparing the cases with decreased, neutral, and increased functional abilities after treatment between old and innovative approaches, we found that the % of cases with increased abilities after innovative treatment was nearly 50%. At the same time, the old LTC method achieved progress in only 10% of patients.

- We also tested the differences between the results of the old and new approaches regarding integrated services to maintain independence. Among the 132 participants in the sample of the MOST programme, 75 users were examined in these services. The interval assessment of the percentage of LTC users for whom the integrated services maintain independence was between 23,27% and 44.26% in more than 97%—compared with the control group, where the autonomy rose only to between 2.52% and 17.82%.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LTC | Long-Term Care |

| CT | Care Team |

| HC | Home Care |

| ADL | Activity of Daily Living |

| IADL | Instrumental Activity of Daily Living |

| IMT | Independence Maintenance Team |

| OGRS | Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia |

| M | Module |

| NBA | The German tool for LTC needs assessment, “Das neue Begutachtungsinstrument” |

| NBA-SLO | The Slovenian tool for LTC needs assessment |

| FA | Functional Abilities |

| NBI | New Assessment Instrument |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A

References

- European Commission. Long-Term Care Needs in the EU on the Rise Due to Demographic Change; European Commission—Joint Research Centre: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The Green Paper on Ageing; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. People Having a Long-Standing Illness or Health Problem, by Sex, Age and Labour Status; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood, K.; Mitnitski, A. Frailty in Relation to the Accumulation of Deficits. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2007, 62, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaddoura, R.; Faraji, H.; Othman, M.; Abu Hijleh, A.; Loney, T.; Goswami, N.; Benamer, H.T.S. Exploring Factors Associated with Falls in Multiple Sclerosis: Insights from a Scoping Review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2024, 19, 923–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Falls. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Socialinterreg. Social Innovation Projects; Interreg Programme Authority & German Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community. 2024. Available online: https://socialinterreg.eu/position-paper-on-social-innovation-in-transnational-cooperation-2/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Rothgang, H. Social Insurance for Long-term Care: An Evaluation of the German Model. Soc. Policy Adm. 2010, 44, 436–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboh, L.; Leon, C.; Qadir, S.; Smith, F.; Francis, S.-A. Frail Older People with Multi-Morbidities in Primary Care: A New Integrated Care Clinical Pharmacy Service. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2018, 40, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melchiorre, M.G.; Lamura, G.; Barbabella, F.; on behalf of ICARE4EU Consortium. eHealth for People with Multimorbidity: Results from the ICARE4EU Project and Insights from the “10 e’s” by Gunther Eysenbach. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nuovo, A.; Broz, F.; Wang, N.; Belpaeme, T.; Cangelosi, A.; Jones, R.; Esposito, R.; Cavallo, F.; Dario, P. The Multi-Modal Interface of Robot-Era Multi-Robot Services Tailored for the Elderly. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2018, 11, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- the DEP-EXERCISE Group; López-Torres Hidalgo, J. Effectiveness of Physical Exercise in the Treatment of Depression in Older Adults as an Alternative to Antidepressant Drugs in Primary Care. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carron, T.; Bridevaux, P.-O.; Lrvall, K.; Parmentier, R.; Moix, J.-B.; Beytrison, V.; Pernet, R.; Rey, C.; Roberfroid, P.-Y.; Chhajed, P.N.; et al. Feasibility, Acceptability and Effectiveness of Integrated Care for COPD Patients: A Mixed Methods Evaluation of a Pilot Community-Based Programme. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2017, 147, w14567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Batlle, J.; Massip, M.; Vargiu, E.; Nadal, N.; Fuentes, A.; Ortega Bravo, M.; Miralles, F.; Barbé, F.; Torres, G.; CONNECARE-Lleida Group. Implementing Mobile Health–Enabled Integrated Care for Complex Chronic Patients: Intervention Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2021, 9, e22135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Personalised Connected Care for Complex Chronic Patients; European Commission—CORDIS: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Round, T.; Ashworth, M.; Crilly, T.; Ferlie, E.; Wolfe, C. An Integrated Care Programme in London: Qualitative Evaluation. J. Integr. Care 2018, 26, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franse, C.B.; Voorham, A.J.J.; Van Staveren, R.; Koppelaar, E.; Martijn, R.; Valía-Cotanda, E.; Alhambra-Borrás, T.; Rentoumis, T.; Bilajac, L.; Marchesi, V.V.; et al. Evaluation Design of Urban Health Centres Europe (UHCE): Preventive Integrated Health and Social Care for Community-Dwelling Older Persons in Five European Cities. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chidume, T. Promoting Older Adult Fall Prevention Education and Awareness in a Community Setting: A Nurse-Led Intervention. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2021, 57, 151392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center za socialno delo Posavje. Projekt Dolgotrajna Oskrba v skupnosti »Most« (Project Long-Term Care in the Community “Most”); Center za socialno delo Posavje: Brežice, Slovenia, 2024; Available online: https://www.csd-slovenije.si/csd-posavje/enota-krsko/most/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Žele, M.; Šućurović, A.; Kegl, B. Kontinuiteta Zdravstvene Obravnave v Patronažnem Varstvu Po Bolnišnični Obravnavi Otročnice, Novorojenčka in Ostalih Pacientov. Obz. Zdr. Nege 2021, 55, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Che, J.; Ren, W. Effect of Intraspinal Anesthesia on Postoperative Recovery in Elderly Patients with Acute Appendicitis: A Retrospective Study. Ann. Ital. Chir. 2024, 95, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontario Health Coalition. Still Waiting: An Assessment of Ontario’s Home Care System after Two Decades of Restructuring; Ontario Health Coalition: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, S.E.; Laurens, V.; Weigel, G.M.; Hirschman, K.B.; Scott, A.M.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Howard, J.M.; Laird, L.; Levine, C.; Davis, T.C.; et al. Care Transitions From Patient and Caregiver Perspectives. Ann. Fam. Med. 2018, 16, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, L.; Knoefel, F.; Gaskowski, P.; Rexroth, D. Medical Comorbidity and Rehabilitation Efficiency in Geriatric Inpatients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001, 49, 1471–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamian, J.; Shainblum, E.; Stevens, J. Accountability Agenda Must Include Home and Community Based Care. Healthc. Pap. 2006, 7, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küpper-Nybelen, J.; Ihle, P.; Deetjen, W.; Schubert, I. Empfehlung rehabilitativer Maßnahmen im Rahmen der Pflegebegutachtung und Umsetzung in der ambulanten Versorgung. Z. Für Gerontol. Geriatr. 2006, 39, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (BMG). Prävention Vor Und Bei Pflegebedürftigkeit; Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (BMG): Berlin, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sims-Gould, J.; Tong, C.E.; Wallis-Mayer, L.; Ashe, M.C. Reablement, Reactivation, Rehabilitation and Restorative Interventions With Older Adults in Receipt of Home Care: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, C.; Damarell, R.A.; Dizon, J.; Ross, P.D.S.; Tieman, J. Rehabilitation, Reablement, and Restorative Care Approaches in the Aged Care Sector: A Scoping Review of Systematic Reviews. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, R.J.; Berg, K.; Lee, K.-A.; Poss, J.W.; Hirdes, J.P.; Stolee, P. Rehabilitation in Home Care Is Associated With Functional Improvement and Preferred Discharge. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 1038–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthun, K.S.; Lillefjell, M.; Anthun, K.S. Reablement in a Small Municipality, a Survival Analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.-Y.; Lin, P.-S.; Hung, P.-L. ADLers Occupational Therapy Clinic. Effects of Community-Based Physical-Cognitive Training, Health Education, and Reablement among Rural Community-Dwelling Older Adults with Mobility Deficits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timonen, V.; Rostgaard, T. Turning the “problem” into the Solution: Hopes, Trends and Contradictions in Home Care Policies for Ageing Populations. In Cultures of Care in Aging; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2018; pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Goodridge, D.; Lawson, J.; Rennie, D.; Marciniuk, D. Rural/Urban Differences in Health Care Utilisation and Place of Death for Persons with Respiratory Illness in the Last Year of Life. Rural. Remote Health 2010, 10, 1349. [Google Scholar]

- Seitz, D.P.; Gill, S.S.; Austin, P.C.; Bell, C.M.; Anderson, G.M.; Gruneir, A.; Rochon, P.A. Rehabilitation of Older Adults with Dementia After Hip Fracture. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogataj, M.; Bogataj, D.; Drobne, S. Planning and Managing Public Housing Stock in the Silver Economy. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 260, 108848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Yang, Y.S.; Cho, E. Transitional Care from Hospital to Home for Frail Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Geriatr. Nur. 2022, 43, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.S.; Dalal, H.; Jolly, K.; Moxham, T.; Zawada, A. Home-Based versus Centre-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; The Cochrane Collaboration; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolee, P.; Lim, S.N.; Wilson, L.; Glenny, C. Inpatient versus Home-Based Rehabilitation for Older Adults with Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review. Clin. Rehabil. 2012, 26, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrà guez Mañas, L.; Garcà a-Sánchez, I.; Hendry, A.; Bernabei, R.; Roller-Wirnsberger, R.; Gabrovec, B.; Liew, A.; Carriazo, A.M.; Redon, J.; Galluzzo, L.; et al. Key Messages for a Frailty Prevention and Management Policy in Europe from the Advantage Joint Action Consortium. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrovec, B.; Veninšek, G.; Samaniego, L.L.; Carriazo, A.M.; Antoniadou, E.; Jelenc, M. The Role of Nutrition in Ageing: A Narrative Review from the Perspective of the European Joint Action on Frailty—ADVANTAGE JA. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 56, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, Å.; Lindelöf, N.; Olofsson, B.; Berggren, M.; Gustafson, Y.; Nordström, P.; Stenvall, M. Effects of Geriatric Interdisciplinary Home Rehabilitation on Independence in Activities of Daily Living in Older People With Hip Fracture: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewin, G.; Allan, J.; Patterson, C.; Knuiman, M.; Boldy, D.; Hendrie, D. A comparison of the home-care and healthcare service use and costs of older Australians randomised to receive a restorative or a conventional home-care service. Health Soc. Care Community 2014, 22, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severin, R.; Berner, P.M.; Miller, K.L.; Mey, J. The Crossroads of Aging: An Intersection of Malnutrition, Frailty, and Sarcopenia. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 2019, 35, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhares, R.M.; Cunha, A.I.L.; Nascimento Da Cruz, S.L.; Aquaroni Ricci, N. Perceptions of Older Adults Living in Long-Term Care Institutions Regarding Recreational Physiotherapy: A Qualitative Study. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2022, 38, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, Z.; Patel, H.; Wijk, H.; Ekman, I.; Olaya-Contreras, P. A Systematic Review on Implementation of Person-Centered Care Interventions for Older People in out-of-Hospital Settings. Geriatr. Nur. 2021, 42, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, X.; Dong, B.; Li, X. Effectiveness of home-based exercise for functional rehabilitation in older adults after hip fracture surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dautzenberg, L.; Beglinger, S.; Tsokani, S.; Zevgiti, S.; Raijmann, R.C.M.A.; Rodondi, N.; Scholten, R.J.P.M.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; Di Nisio, M.; Emmelot-Vonk, M.; et al. Interventions for Preventing Falls and Fall-related Fractures in Community-dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 2973–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsutake, S.; Ishizaki, T.; Tsuchiya-Ito, R.; Uda, K.; Jinnouchi, H.; Ueshima, H.; Matsuda, T.; Yoshie, S.; Iijima, K.; Tamiya, N. Effects of Early Postdischarge Rehabilitation Services on Care Needs–Level Deterioration in Older Adults With Functional Impairment: A Propensity Score–Matched Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 1715–1722.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia—OGRS [Uradni List RS]. No. 196/21. Long Term Care Act [Zakon o Dolgotrajni Oskrbi] (ZDOsk). Available online: https://www.uradni-list.si/glasilo-uradni-list-rs/vsebina/2021-01-3898 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia—OGRS [Uradni List RS] No 84/23. Long Term Care Act [Zakon o Dolgotrajni Oskrbi] (ZDOsk-1). Available online: https://www.uradni-list.si/glasilo-uradni-list-rs/vsebina/2023-01-2570 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia—OGRS [Uradni List RS], No 112/24. Act Amending the Long-Term Care Act (ZDOsk-1A). Available online: https://www.uradni-list.si/glasilo-uradni-list-rs/vsebina/2024-01-3720/zakon-o-spremembah-in-dopolnitvah-zakona-o-dolgotrajni-oskrbi-zdosk-1a (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Drobež, E.; Bogataj, D. Legal Aspects of Social Infrastructure for Housing and Care for the Elderly—The Case of Slovenia. Laws 2022, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Slovenia, Ministry of Health. Javni Razpis Za Izbiro Operacij »Izvedba Pilotnih Projektov, Ki Bodo Podpirali Prehod v Izvajanje Sistemskega Zakona o Dolgotrajni Oskrbi«; Republic of Slovenia, Ministry of Health: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kobal Straus, K.; Nagode, M. (Eds.) Long-Term Care—A Challenge and Opportunity for a Better Tomorrow. Evaluation of Pilot Projects in the Field of Long-Term Care; Ministry of Health: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2022; p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- Mežnarec Novosel, S.; Bogataj, D.; Rogelj, V. Integration of Telecare into the National Long-Term Care—System The Case of Slovenia. IFAC-Pap. 2022, 55, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OGRS. Act on the Social Protection of Mentally and Physically Disabled Persons [Zakon o Družbenem Varstvu Duševno in Telesno Prizadetih Oseb] (ZDVDTP). Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia [Uradni List RS], No. 41/83, 114/06-ZUTPG, 122/07 Odl.US: U-I-11/07-45, 61/10-ZSVarPre, 40/11-ZSVarPre-A, 30/18-ZSVI. 1983. Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO1866 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- OGRS. Health Care and Health Insurance Act [Zakon o Zdravstvenem Varstvu in Zdravstvenem Zavarovanju (ZZVZZ). Official Gazette of the Republik of Slovenia [Uradni List RS], No. 72/06—Official Consolidated Text, 114/06—ZUTPG, 91/07, 76/08, 62/10—ZUPJS, 87/11, 40/12—ZUJF, 21/13—ZUTD-A, 91/13, 99/13—ZUPJS-C, 99/13—ZSVarPre-C, 111/13—ZMEPIZ-1, 95/14—ZUJF-C, 47/15—ZZSDT, 61/17—ZUPŠ, 64/17—ZZDej-K, 36/19, 189/20—ZFRO, 51/21, 159/21, 196/21—ZDOsk, 15/22, 43/22, 100/22—ZNUZSZS, 141/22—ZNUNBZ, 40/23—ZČmIS-1 in 78/23. 1992. Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO213 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- OGRS. War Veterans Act [Zakon o Vojnih Veteranih] (ZVV). Official Gazette of the Republik of Slovenia [Uradni List RS], No. 59/06—Official Consolidated Text, 61/06—ZDru-1, 101/06—Odl. US, 40/12—ZUJF, 32/14, 21/18—ZNOrg, 174/20—ZIPRS2122, 78/23—ZZVZZ-T in 84/23—ZDOsk-1. 1995. Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO963 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- OGRS. War Disabled Persons Act [Zakon o Vojnih Invalidih] (ZVojI). Official Gazette of the Republik of Slovenia [Uradni List RS], No. 63/95, 21/97—Popr., 2/97—Odl. US, 19/97, 75/97, 11/06—Odl. US, 61/06—ZDru-1, 114/06—ZUTPG, 40/12—ZUJF, 19/14, 21/18—ZNOrg, 174/20—ZIPRS2122, 159/21 in 78/23—ZZVZZ-T. 1995. Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO961 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- OGRS. Acts on Social Benefits and Social Welfare Services [Zakon o Socialnem Varstvu] (ZSV). Official Gazette of the Republik of Slovenia [Uradni List RS], No. 3/07—Official Consolidated Text, 23/07—Correc., 41/07—Correc., 61/10—ZSVarPre, 62/10—ZUPJS, 57/12, 39/16, 52/16—ZPPreb-1, 15/17—DZ, 29/17, 54/17, 21/18—ZNOrg, 31/18—ZOA-A, 28/19, 189/20—ZFRO, 196/21—ZDOsk, 82/23 in 84/23—ZDOsk-1. 2007. Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO869 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- OGRS. Financial Social Assistance Act [Zakon o Socialno Varstvenih Prejemkih] (ZSVarPre). Official Gazette of the Republik of Slovenia [Uradni List RS], No. 61/2010, 40/2011, 110/2011-ZDIU12, 40/2012-ZUJF, 14/2013, 99/2013, 90/2015, 88/2016, 31/2018. 2010. Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO5609 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- OGRS. Exercise of Rights to Public Funds Act [Zakon o Uveljavljanju Pravic Iz Javnih Sredstev] (ZUPJS). Official Gazette of the Republik of Slovenia [Uradni List RS], No. 62/2010, 40/2011, 110/2011-ZDIU12, 40/2012-ZUJF, 57/2012-ZPCP-2D, 14/2013, 56/2013-ZŠtip-1, 99/2013, 46/2014-ZŠolPre-1A, 14/2015-ZUUJFO, 57/2015, 90/2015, 38/2016 Odl. US: U-I-109/15-14, 51/2016 Odl. US: U-I-73/15-28, 88/2016, 61/2017-ZUPŠ, 75/2017, 77/2018, 47/2019, 175/2020-ZIUOPDVE, 189/2020-ZFRO, 54/2022-ZUPŠ-1, 76/2023-ZŠolPre-1B, 95/2023-ZIUOPZP, 122/2023-ZŠtip-1C, 131/2023-ZORZFS, 136/2023-ZIUZDS. 2010. Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO4780 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- OGRS. Pension and Disability Insurance Act [Zakon o Pokojninskem in Invalidskem Zavarovanju] (ZPIZ-2). Official Gazette of the Republik of Slovenia [Uradni List RS], No. 48/22—Official Consolidated Text, 40/23—ZČmIS-1, 78/23—ZORR, 84/23—ZDOsk-1, 125/23—Odl. US and 133/23. 2012. Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO6280 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- OGRS. Parental Care and Family Benefits Act [Zakon o Starševskem Varstvu in Družinskih Prejemkih] (ZSDP-1). Official Gazette of the Republik of Slovenia [Uradni List RS], No. 26/14, 90/15, 75/17—ZUPJS-G, 14/18, 81/19, 158/20, 92/21, 153/22. 2014. Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO6688 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- German Federal Ministry of Justice Sozialgesetzbuch (SGB) - Elftes Buch (XI) - Soziale Pflegeversicherung 2014. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/sgb_11/ (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Franke, N. Pflegegrade Und Die Neuen Begutachtungsrichtlinien: Praxishandbuch Für Die Erfolgreiche Umsetzung Im Pflege—Und Betreuungsprozess; Vincentz Network: Hanover, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-7486-0159-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of Slovenia. Priročnik Za Uporabo Ocenjevalne Lestvice Za Oceno Upravičenosti Do Dolgotrajne Oskrbe [Manual for Using the Long-Term Care Eligibility Assessment Scale]; Ministry of Health of the Republic of Slovenia: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Pflegeversicherung; Bundesministerium für Gesundheit—BMG: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barczyk, D.; Kredler, M. Long-Term Care Across Europe and the United States: The Role of Informal and Formal Care. Fisc. Stud. 2019, 40, 329–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OGRS Regulation on the Rating Scale for Assessing Eligibility for Long-Term Care [Pravilnik o Ocenjevalni Lestvici Za Oceno Upravičenosti Do Dolgotrajne Oskrbe] Official Gazet of the Republic of Slovenija [Uradni List RS], No. 2/24. Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=PRAV15178 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Federal Gazette Sozialgesetzbuch Neuntes Buch—Rehabilitation Und Teilhabe von Menschen Mit Behinderungen (SGB IX). 2016. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/sgb_9_2018/BJNR323410016.html (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Federal Gazette Das Fünfte Buch Sozialgesetzbuch—Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung. 1988. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/sgb_5/BJNR024820988.html (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Agresti, A.; Caffo, B. Simple and Effective Confidence Intervals for Proportions and Differences of Proportions Result from Adding Two Successes and Two Failures. Am. Stat. 2000, 54, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inui, T.S. The Need for an Integrated Biopsychosocial Approach to Research on Successful Aging. Ann. Intern. Med. 2003, 139, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angevaren, M.; Aufdemkampe, G.; Verhaar, H.; Aleman, A.; Vanhees, L. Physical Activity and Enhanced Fitness to Improve Cognitive Function in Older People without Known Cognitive Impairment. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; The Cochrane Collaboration; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogelj, V.; Bogataj, D.; Bogataj, M.; Campuzano-Bolarín, F.; Drobež, E. The Role of Housing in Sustainable European Long-Term Care Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogataj, M.; Drobez, E.; Rogelj, V.; Drobez, M.; Bogataj, D. Capacity Planning for Social Infrastructure of Smart Lifetime Neighbourhoods: Social Value Approach. IFAC-Pap. 2022, 55, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepura, A.; Masaki, H.; Wild, D.; Nomura, T.; Collinson, M.; Kneafsey, R. Integrated Long-Term Care ‘Neighbourhoods’ to Support Older Populations: Evolving Strategies in Japan and England. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, T.N.N.; Lorga, T.; Moolphate, S.; Koyanagi, Y.; Angkurawaranon, C.; Supakankunti, S.; Yuasa, M.; Aung, M.N. Towards Cultural Adequacy of Experience-Based Design: A Qualitative Evaluation of Community-Integrated Intermediary Care to Enhance the Family-Based Long-Term Care for Thai Older Adults. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chang, Y.-C.; Hu, W.-Y. The Effectiveness of Palliative Care Interventions in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mežnarec Novosel, S.; Campuzano Bolarin, F.; Bogataj, D. Vpliv Gostote Prebivalstva Na Strukturo Storitev Dolgotrajne Oskrbe = Influence of Population Density on the Structure of Long-Term Care Services. In Prostorski in Socio-Ekonomski Vidiki v Študijah Staranja = Spatial and Socio-Economic Aspects in Ageing Studies; Alma Mater Europaea University, Alma Mater Press: Maribor, Slovenia, 2024; pp. 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Chen, S.; Xiao, G. Advancing Healthcare through Mobile Collaboration: A Survey of Intelligent Nursing Robots Research. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1368805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Standard Long-Term Care | Integrated Long-Term Care |

|---|---|

| Evaluation performed by LTC and HC service providers | Single entry point |

| Determination of the necessary category of care—only for applicants for institutional care | Determining the care category with an individual plan for all LTC applicants |

| Various assessment tools | The new uniform assessment tool NBA-SLO |

| More rights for beneficiaries in institutional care | Equalisation of the rights of beneficiaries in all forms of care |

| Standard non-personalised care | Person-centred care |

| Independent service provision by each caregiver | Teamwork |

| Separate social and health care services | Connected and coordinated services of different providers |

| Only social care in Home Care Healthcare is separated | Care team, including social, medical staff and independent maintenance team in Home Care |

| Services for Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) | Services for ADL, IADL, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, other medical and social care, e-care |

| Modules | Scoring | Points/Severity Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ability to move in the environment where the insured lives | The sum of points in M1 | 0–1 | 2–3 | 4–5 | 6–9 | 10–15 |

| Weights for M1 | 0 | 2.5 | 5 | 7.5 | 10 | |

| Cognitive and communication skills | The sum of points in M2 | 0–1 | 2–5 | 6–10 | 11–16 | 17–33 |

| Weights for M2 | 0 | 3.75 | 7.5 | 11.25 | 15 | |

| Behaviour and mental health | The sum of points in M3 | 0 | 1–2 | 3–4 | 5–6 | 7–65 |

| Weights for M3 | 0 | 3.75 | 7.5 | 11.25 | 15 | |

| Weights for M2/M3 | 0 | 3.75 | 7.5 | 11.25 | 15 | |

| Self-care ability | The sum of points in M4 | 0–2 | 3–7 | 8–18 | 19–36 | 37–54 |

| Weights for M4 | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | |

| Ability to cope with the disease and the demands and burdens associated with the treatment | The sum of points in M5 | 0 | 1 | 2–3 | 4–5 | 6–15 |

| Weights for M5 | 0 | 3.75 | 7.5 | 11.25 | 15 | |

| Course of everyday life and social contacts | The sum of points in M6 | 0 | 1–3 | 4–6 | 7–11 | 12–18 |

| Weights for M6 | 0 | 2.5 | 5 | 7.5 | 10 | |

| Ability to be active outside the home environment | The sum of Points in M7 | 0–6 | 7–10 | 11–14 | 15–17 | 18–21 |

| Weights for M7 | 0 | 2.5 | 5 | 7.5 | 10 | |

| Weighted for M6/M7 | 0 | 2.5 | 5 | 7.5 | 10 | |

| Ability to perform household chores in the environment where the insured lives | The sum of points in M8 | 0–6 | 7–8 | 9–11 | 12–14 | 15–18 |

| Weights for M8 | 0 | 2.5 | 5 | 7.5 | 10 | |

| Categories of Care | Admission | Rating with NBA-SLO (Weighted Points) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Ineligible | [0–12.40] |

| 1 | Eligible for LTC services under Category 1 | [12.50–26.99] |

| 2 | Eligible for LTC services under Category 2 | [27.00–47.49] |

| 3 | Eligible for LTC services under Category 3 | [47.50–69.99] |

| 4 | Eligible for LTC services under Category 4 | [70.00–89.99] |

| 5 | Eligible for LTC services under Category 5 | [90.00–100.00] |

| Services | |

|---|---|

| S1. Assessment and evaluation—interview | S9. Psychosocial support for users |

| S2. Team/stakeholder involvement, coordinator reporting | S10. Social inclusion support |

| S3. Counselling on environmental adaptations | S11. Short telephone consultation (≤15 min) |

| S4. Training for informal caregivers | S12. Informing formal providers (GPs, nurses) |

| S5. Prevention, counselling, empowerment | S13. Hospital/residential care admission support |

| S6. Mobility support: strength, flexibility, fall prevention | S14. Safe discharge planning |

| S7. Chronic disease counselling | S15. Volunteer onboarding and support |

| S8. Health promotion for informal caregivers | S16. Extended telephone consultation (>15 min) |

| Modules | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | 41 | 12 | 23 | 30 | 39 | 28 | 41 | 24 |

| N | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 |

| p = X/N | 0.3106 | 0.0909 | 0.1742 | 0.2273 | 0.2955 | 0.2121 | 0.3106 | 0.1818 |

| p′ =(X + 1)/(N + 2) | 0.3134 | 0.0970 | 0.1791 | 0.2313 | 0.2985 | 0.2164 | 0.3134 | 0.1866 |

| SE2 | 0.0049 | 0.0058 | 0.0057 | 0.0054 | 0.0050 | 0.0055 | 0.0049 | 0.0056 |

| SE | 0.0699 | 0.0764 | 0.0752 | 0.0734 | 0.0706 | 0.0740 | 0.0699 | 0.0750 |

| 1.96*SE | 0.1371 | 0.1498 | 0.1474 | 0.1439 | 0.1384 | 0.1450 | 0.1371 | 0.1469 |

| Upper limit p′ | 0.4505 | 0.2468 | 0.3265 | 0.3752 | 0.4369 | 0.3614 | 0.4505 | 0.3335 |

| Lower limit p′ | 0.1764 | −0.0528 | 0.0317 | 0.0875 | 0.1601 | 0.0715 | 0.1764 | 0.0396 |

| Entitled to LTC | − | o | + | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X- | % | Xo | % | X+ | % | N | % | |

| Under integrated approach | 6 | 8 | 32 | 42.7 | 37 | 49.3 | 75 | 100 |

| Under standard approach | 15 | 26.3 | 37 | 64.9 | 5 | 8.8 | 57 | 100 |

| Total | 21 | 15.9 | 69 | 52.3 | 42 | 31.8 | 132 | 100 |

| Groups | Under Integrated Services to Maintain Independence | Control Group |

|---|---|---|

| X | 25 | 5 |

| N | 75 | 57 |

| p = X/N | 0.3333 | 0.0877 |

| p′ = (X + 1)/(N + 2) | 0.3377 | 0.1017 |

| SE2 | 0.0029 | 0.0015 |

| SE | 0.0535 | 0.0390 |

| 1.96*SE | 0.1050 | 0.0765 |

| Upper limit p | 0.4426 | 0.1782 |

| Lower limit p | 0.2327 | 0.0252 |

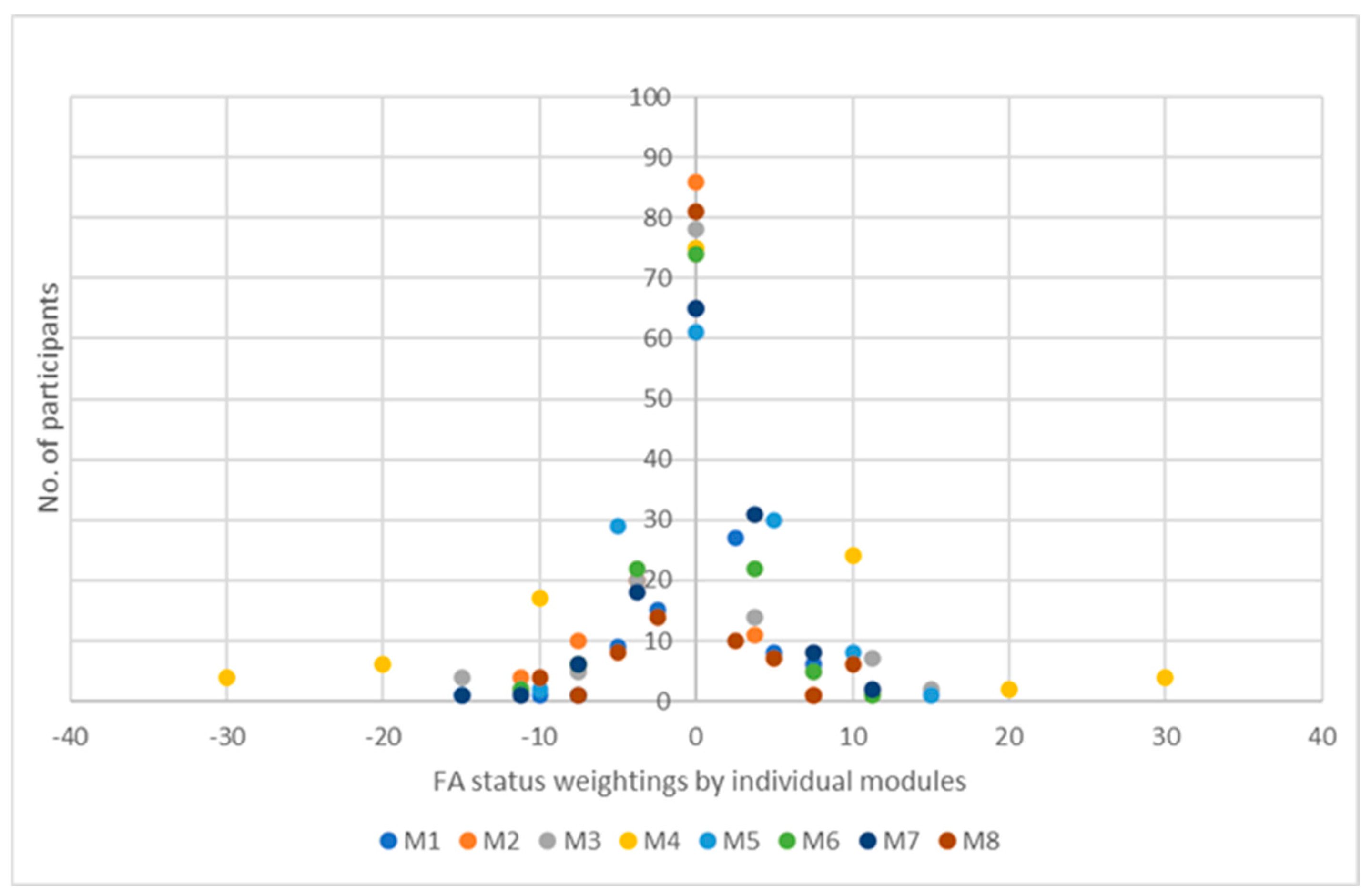

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | Weighted Ratings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −40 | ||||||||

| 4 | −30 | |||||||

| 6 | −20 | |||||||

| 4 | 1 | 1 | −15 | |||||

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | −11.25 | ||||

| 1 | 17 | 2 | 4 | −10 | ||||

| 1 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 1 | −7.5 | ||

| 9 | 29 | 8 | −5 | |||||

| 20 | 20 | 22 | 18 | −3.75 | ||||

| 15 | 14 | −2.5 | ||||||

| 26 | 34 | 31 | 27 | 32 | 30 | 26 | 27 | - Deterioration: sum in No. of participants |

| 65 | 86 | 78 | 75 | 61 | 74 | 65 | 81 | 0—Status preserved: No. of participants |

| 41 | 12 | 23 | 30 | 39 | 28 | 41 | 24 | ₊ Improving totals in No. of part. |

| 27 | 10 | 2.5 | ||||||

| 11 | 14 | 22 | 31 | 3.75 | ||||

| 8 | 30 | 7 | 5 | |||||

| 6 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 7.5 | |||

| 24 | 8 | 6 | 10 | |||||

| 7 | 1 | 2 | 11.25 | |||||

| 2 | 1 | 15 | ||||||

| 2 | 20 | |||||||

| 4 | 30 | |||||||

| 40 | ||||||||

| 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | Sample |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mežnarec-Novosel, S.; Bogataj, M.; Bogataj, D.; Drobež, E. Effectiveness of New Reactivation Approaches in Integrated Long-Term Care—Contribution to the Long-Term Care Act. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101187

Mežnarec-Novosel S, Bogataj M, Bogataj D, Drobež E. Effectiveness of New Reactivation Approaches in Integrated Long-Term Care—Contribution to the Long-Term Care Act. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101187

Chicago/Turabian StyleMežnarec-Novosel, Suzanna, Marija Bogataj, David Bogataj, and Eneja Drobež. 2025. "Effectiveness of New Reactivation Approaches in Integrated Long-Term Care—Contribution to the Long-Term Care Act" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101187

APA StyleMežnarec-Novosel, S., Bogataj, M., Bogataj, D., & Drobež, E. (2025). Effectiveness of New Reactivation Approaches in Integrated Long-Term Care—Contribution to the Long-Term Care Act. Healthcare, 13(10), 1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101187