Association Between Financial Support and Physical Health in Older People: Evidence from CHARLS Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Variable Selection

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variable

3.2.3. Controlled Variables

3.3. Model Construction

- Construct the regression equation of the influence of financial support on the physical health of older people (3);

- If the regression coefficient of financial support is significant, then the regression Equation (4) of the influence of financial support on the intermediary variables and the regression Equation (5) of the influence of financial support and intermediary variables on the physical health of older people are constructed to test whether the intermediary effect exists.

4. Results

4.1. Basic Regression

4.2. Robustness Test

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

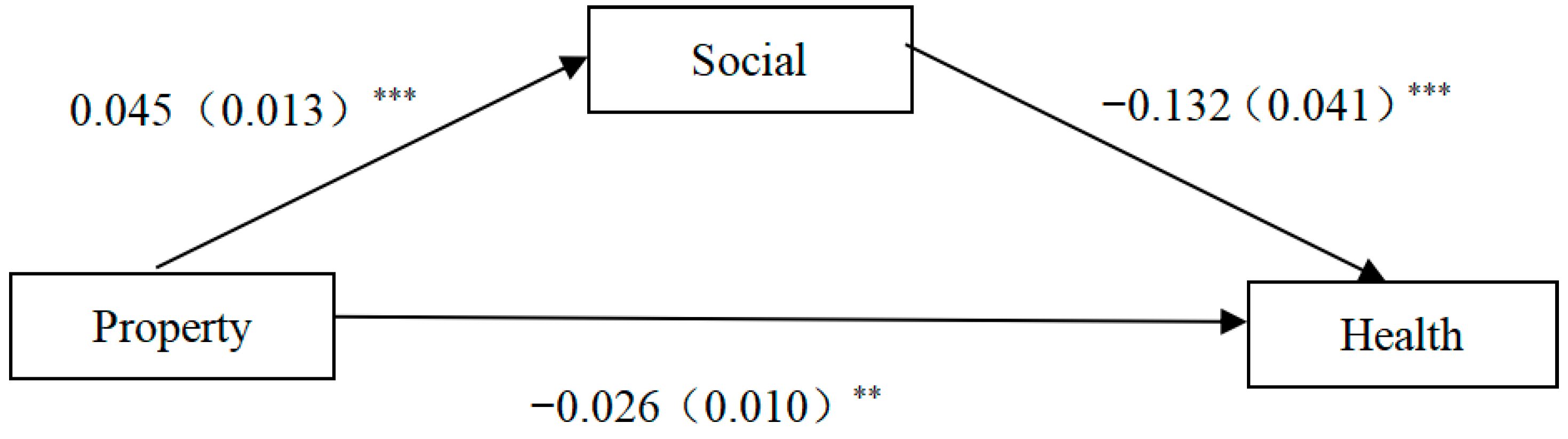

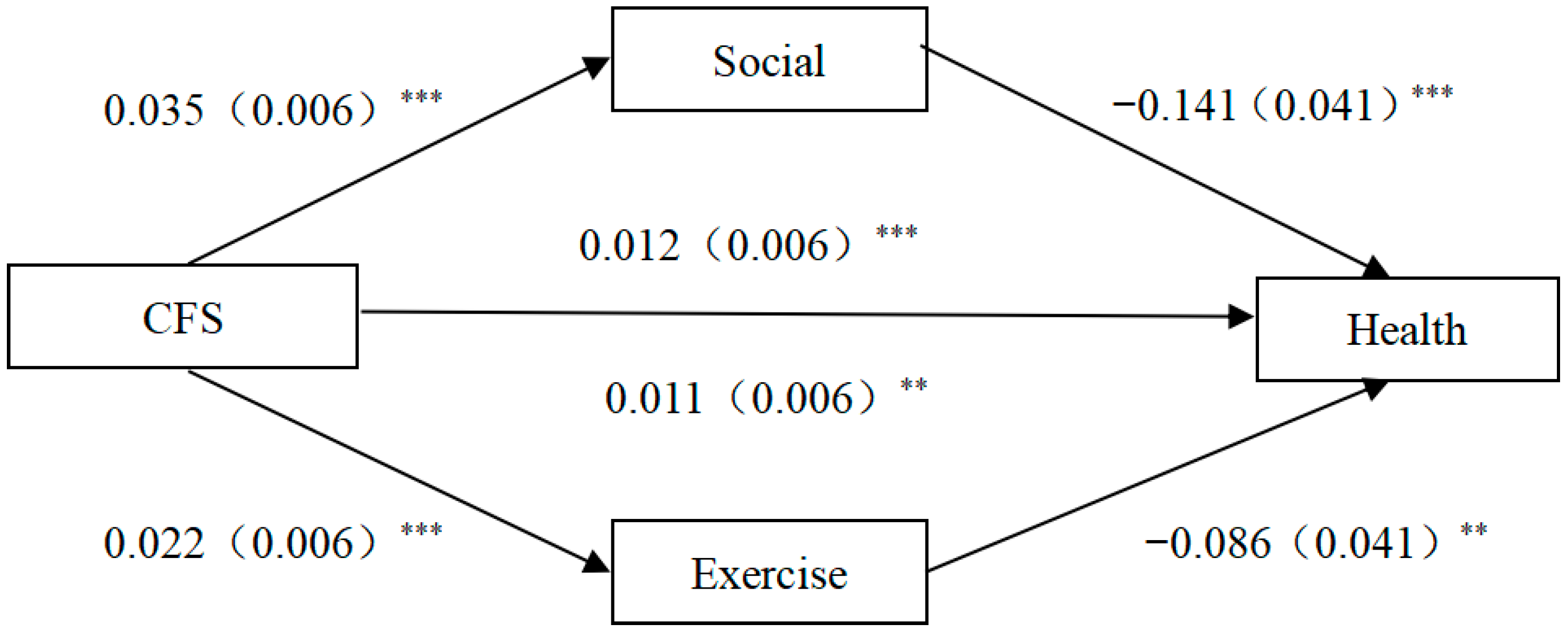

4.4. The Mechanism of Financial Support on the Physical Health of Older People

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary

5.2. Policy Implications

5.3. Strengths

5.4. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lopez, A.D.; Adair, T. Slower increase in life expectancy in Australia than in other high income countries: The contributions of age and cause of death. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 210, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoppa, L.J. The policy response to declining fertility rates in Japan: Relying on logic and hope over evidence. Soc. Sci. Jpn. J. 2020, 23, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Population aging and fiscal sustainability: An international comparison. Stud. Labor Econ. 2021, 9, 26–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, F. Implementing a national strategy for responding proactively to population aging. Stud. Labor Econ. 2020, 8, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Fang, X. The social pension scheme and the subjective well-being of the elderly in rural China. J. Financ. Econ. 2018, 44, 80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Xin, Y. The impact of family financial support on the health of the elderly in urban areas. Tax. Econ. 2023, 35, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X. China’s demographic history and future challenges. Science 2011, 333, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Du, P. Old-Age support or carrying on the family line—Research on the role expectation of children for Chinese elderly and the influencing factors. Popul. Dev. 2023, 29, 100–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y. Re-employment after Retirement or Continue to Work without Retirement? An Analysis of the Remaining Working Life of the Elders in the Urban and Rural Areas Based on Multi-state life Table. South China Popul. 2024, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Tang, Y.; Mao, Q. Exploration of the Evolution of Senior Housing Policy System and Diversified Implementation Methods with the Canadian Senior Housing Program as a Case. Urban Dev. Stud. 2024, 31, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Fu, Y. Physical attributes of housing and elderly health: A new dynamic perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rent, P.D.; Kumar, S.; Dmello, M.K.; Purushotham, J. Psychosocial status and economic dependence for healthcare and nonhealthcare among elderly population in rural coastal Karnataka. J. Mid-Life Health 2017, 8, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wu, B.; Yi, F.; Wang, B.; Baležentis, T. What happens to the health of elderly parents when adult child migration splits households? Evidence from rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Research on the impact of family support on the health of the elderly. World Surv. Res. 2022, 35, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Frimmel, W. Later retirement and the labor market re-integration of elderly unemployed workers. J. Econ. Ageing 2021, 19, 10031019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Du, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Study on the Effects of Intergenerational Support on Hypertension among Older Adults. Chin. Health Serv. Manag. 2025, 42, 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Donini, L.M.; Scardella, P.; Piombo, L.; Neri, B.; Asprino, R.; Proietti, A.; Carcaterra, S.; Cava, E.; Cataldi, S.; Cucinotta, D.; et al. Malnutrition in elderly: Social and economic determinants. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2013, 17, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q. How Does Socioeconomic Status Affect Health Among Older Adults? The Mediating and Moderating Roles of Internet Use. J. Soc. Dev. 2024, 11, 96–118+244. [Google Scholar]

- Du, P.; Wang, B. How does internet use affect life satisfaction of the Chinese elderly? Popul. Res. 2020, 44, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Si, M.; Ai, D.; Huang, X.; Liang, D.; Xu, J. Researches on the impact of lifestyle on the mental health of the urban elderly in China based on the empirical analysis of CHARLS 2018. Chin. Health Serv. Manag. 2023, 40, 552–556. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, C.; He, W. Influence of Intergenerational Support on the Health of the Elderly: Re-examination Based on the Endogenous Perspective. Popul. Econ. 2021, 43, 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, M. Research on Elderly Medical Service Utilization under the Background of Healthy Aging: From the Dual Perspectives of Generational Economic Support and Medical Insurance. Mod. Manag. Sci. 2023, 42, 96–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, X.; Feng, X. Intergenerational support and health of the rural elderly—Based on families of returning migrant workers. Popul. Dev. 2023, 29, 122–137. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Ge, R.; Dong, Z.; Zheng, W.; Jing, Q. Study on the Contribution of Influencing Factors and Group Heterogeneity of the Self-Rated Health Status of the Elderly Migrants. Chin. Health Serv. Manag. 2024, 41, 701–705. [Google Scholar]

- Carmel, S.; Bernstein, J.H. Gender differences in physical health and psychosocial well-being among four age-groups of elderly people in Israel. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2003, 56, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, Y. Socioeconomic status and physical health of older adults: Mechanism analyses based on health screening. J. Soc. Dev. 2023, 10, 136–157+244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum, G.G.; Blay, S.L.; Pieper, C.F.; King, K.E.; Andreoli, S.B.; Gastal, F.L. The association of health and income in the elderly: Experience from a southern state of Brazil. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Jeong, G.-C.; Yim, J. Consideration of the psychological and mental health of the elderly during COVID-19: A theoretical review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goethals, L.; Barth, N.; Guyot, J.; Hupin, D.; Celarier, T.; Bongue, B. Impact of home quarantine on physical activity among older adults living at home during the COVID-19 pandemic: Qualitative interview study. JMIR Aging 2020, 3, e19007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, H.; Pan, L.; Tu, J.; Shan, G. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in China during 2002–2022: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 93, 102165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.J.; Sohn, H.S.; Lee, E.K.; Kwon, J.W. Living arrangements, chronic diseases, and prescription drug expenditures among Korean elderly: Vulnerability to potential medication underuse. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Q.; Ren, X. Effect of intergenerational support from children on older adults healthcare seeking behaviors. J. Sichuan Univ. (Med. Sci.) 2023, 54, 614–619. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Z. An exploration on the multiple paths for county to actively respond to the aging of rural population under the strategy of rural revitalization. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2023, 44, 144–151. [Google Scholar]

- Nouri, A.; Farsi, S. Expectations of institutionalized elderly from their children. Salmand Iran. J. Ageing 2018, 13, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Fu, Y.C. Leisure participation and enjoyment among the elderly: Individual characteristics and sociability. Educ. Gerontol. 2008, 34, 871–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, P.; Paswan, B. Lifestyle behaviours and mental health outcomes of elderly: Modification of socio-economic and physical health effects. Ageing Int. 2021, 46, 35–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fan, C.; Tian, L.; Ouyang, W.; Miao, W. Study on the impact of neighborhood built environment on social activities of elderly. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 36, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L. Evaluation of Chinese Urban Employees’ Retirement Behavior Rationality: From the Perspective of Health Heterogeneity. Stat. Res. 2024, 41, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, F.; Sun, T. Analysis of the Health Effects and Mechanisms of Self-Employed Employment in the Context of Delayed Retirement Based on the Empirical Evidence from Older Workers in CHARLS. Chin. Health Serv. Manag. 2024, 41, 1004–1009+1042. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Description | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Very good | 940 | 9.98% |

| Good | 1075 | 11.42% | |

| Fair | 4699 | 49.90% | |

| Poor | 2004 | 21.28% | |

| Very poor | 699 | 7.42% | |

| Property_s | No | 9030 | 95.89% |

| Yes | 387 | 4.11% | |

| CFS_s | No | 3300 | 35.04% |

| Yes | 6117 | 64.96% | |

| Exercise | No | 4473 | 47.50% |

| Yes | 4944 | 52.50% | |

| Social | No | 5111 | 54.27% |

| Yes | 4306 | 45.73% | |

| Gender | Male | 4575 | 48.58% |

| Female | 4842 | 51.42% | |

| Education | Uneducated (illiterate) | 2749 | 29.19% |

| Did not finish primary school | 2196 | 23.32% | |

| Graduated from private school | 17 | 0.18% | |

| Graduated from primary school | 1998 | 21.22% | |

| Graduated from junior high school | 1513 | 16.07% | |

| Graduated from high school | 575 | 6.11% | |

| Graduate from technical secondary school | 223 | 2.37% | |

| College graduate | 88 | 0.93% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 53 | 0.56% | |

| Master’s degree | 3 | 0.03% | |

| Graduate with a PhD | 2 | 0.02% | |

| Married | Unmarried | 57 | 0.61% |

| Married | 9360 | 99.39% | |

| Household_t | Rural | 6924 | 73.53% |

| Urban | 2493 | 26.47% | |

| Pension | No | 1821 | 19.34% |

| Yes | 7596 | 80.66% | |

| COVID2 | Increased greatly | 41 | 0.44% |

| Increased slightly | 37 | 0.39% | |

| No changed | 3930 | 41.73% | |

| Decreased slightly | 825 | 8.76% | |

| Decreased greatly | 4584 | 48.68% | |

| Urban | City center or town center | 2160 | 22.94% |

| Combination zone between urban and rural | 998 | 10.60% | |

| Village | 6252 | 66.39% | |

| Special area | 7 | 0.07% |

| Variable | Observation | M | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Property | 9417 | 0.368 | 1.806 | 0 | 12.206 |

| CFS | 9417 | 5.186 | 3.945 | 0 | 12.255 |

| Age | 9417 | 68.346 | 6.250 | 60 | 108 |

| Offspring | 9417 | 2.841 | 1.373 | 0 | 10 |

| Income | 9417 | 1.153 | 3.041 | 0 | 11.695 |

| COVID1 | 9231 | 20.233 | 30.333 | 0 | 240 |

| Variables | Health | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Property | −0.034 *** (0.010) | −0.027 *** (0.010) | ||

| CFS | 0.016 *** (0.005) | 0.010 ** (0.006) | ||

| Gender | 0.166 *** (0.044) | 0.162 *** (0.044) | ||

| Age | 0.005 (0.004) | 0.005 (0.004) | ||

| Education | −0.017 (0.013) | −0.020 (0.013) | ||

| Married | −0.037 (0.302) | −0.067 (0.302) | ||

| Household_t | −0.182 *** (0.055) | −0.181 *** (0.055) | ||

| Offspring | 0.014 (0.019) | 0.006 (0.019) | ||

| Income | −0.070 *** (0.007) | −0.070 *** (0.007) | ||

| Pension | −0.066 (0.056) | −0.071 (0.056) | ||

| COVID1 | 0.002 *** (0.001) | 0.003 *** (0.001) | ||

| COVID2 | 0.030 (0.022) | 0.027 (0.022) | ||

| City | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.017 | 0.025 | 0.017 | 0.025 |

| N | 9417 | 9231 | 9417 | 9231 |

| Variables | Alternate Explanatory Variable | Narrow Down the Sample | Change Control Variable | Using 2018 Data | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Property | −0.027 ** (0.011) | −0.025 ** (0.011) | |||||

| CFS | 0.010 * (0.006) | 0.012 ** (0.006) | |||||

| Property_s | −0.248 *** (0.095) | ||||||

| CFS_s | 0.099 ** (0.046) | ||||||

| Financial support | −0.438 *** (0.166) | ||||||

| Urban | 0.118 *** (0.029) | 0.123 *** (0.029) | |||||

| Controlled variables | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| City | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.032 |

| N | 9231 | 9231 | 9117 | 9117 | 9231 | 9231 | 5887 |

| Variables | Age | Household_t | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) 60–69 Years Old | (2) Age 70 and Older | (3) Urban | (4) Rural | |

| Property | −0.021 * (0.012) | −0.053 ** (0.024) | −0.007 (0.018) | −0.053 *** (0.014) |

| CFS | 0.008 (0.007) | 0.018 * (0.010) | 0.013 (0.011) | 0.010 (0.007) |

| Controlled variables | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| City | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.028 | 0.034 | 0.040 | 0.028 |

| N | 5940 | 3291 | 2466 | 6765 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, E.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, L. Association Between Financial Support and Physical Health in Older People: Evidence from CHARLS Data. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101163

Guo E, Li J, Sun Y, Zheng L. Association Between Financial Support and Physical Health in Older People: Evidence from CHARLS Data. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101163

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Enkai, Jing Li, Yiyuan Sun, and Lan Zheng. 2025. "Association Between Financial Support and Physical Health in Older People: Evidence from CHARLS Data" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101163

APA StyleGuo, E., Li, J., Sun, Y., & Zheng, L. (2025). Association Between Financial Support and Physical Health in Older People: Evidence from CHARLS Data. Healthcare, 13(10), 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101163