Aging in Place and Healthcare Equity: Using Community Partnerships to Influence Health Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. What Is Aging in Place, and Where Are the Current Gaps?

1.2. The Ecology of AIP

1.3. Access to Safe, Livable Housing Is Not Evenly Distributed

1.4. A Community-Based Organization Intervention and Mediating Barriers to AIP

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADL | Activities of daily living |

| AIP | Aging in place |

| CBO | Community-based organization |

| IADL | Instrumental activities of daily living |

| NIA | National Institutes of Aging |

| NIMHD | National Institute of Minority Health Disparity |

| OT | Occupational Therapy/Occupational Therapists |

| RT-N | Rebuilding Together National |

| RT-R | Rebuilding Together Richmond |

References

- Aging in Place: Growing Older at Home. 2023. Available online: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/aging-place/aging-place-growing-older-home (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- National Association of Home Builders. Certified Aging-in-Place Specialist (CAPS). Available online: https://www.nahb.org/education-and-events/credentials/certified-aging-in-place-specialist-caps (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Resnick, B.; Brandt, N.; Holmes, S.; Klinedinst, N.J. Feasibility of aging in place clinics in low income senior housing. Geriatr. Nurs. 2024, 59, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oswald, F.; Wahl, H.-W.; Wanka, A.; Chaudhury, H. Theorizing place and aging: Enduring and novel issues in environmental gerontology. In Handbook of Aging and Place; Cutchin, M.P., Rowles, G.D., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Oswald, F.; Adkins-Jackson; Greenfield, E.A. Frameworks for Aging in Place. In Aging in Place with Dementia: Proceedings of a Workshop; National Academies of Sciences EaM, Ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes, M.E. A city within a city: A “snapshot” of aging in a HUD 202 in Detroit, Michigan. J. Aging Stud. 2011, 25, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

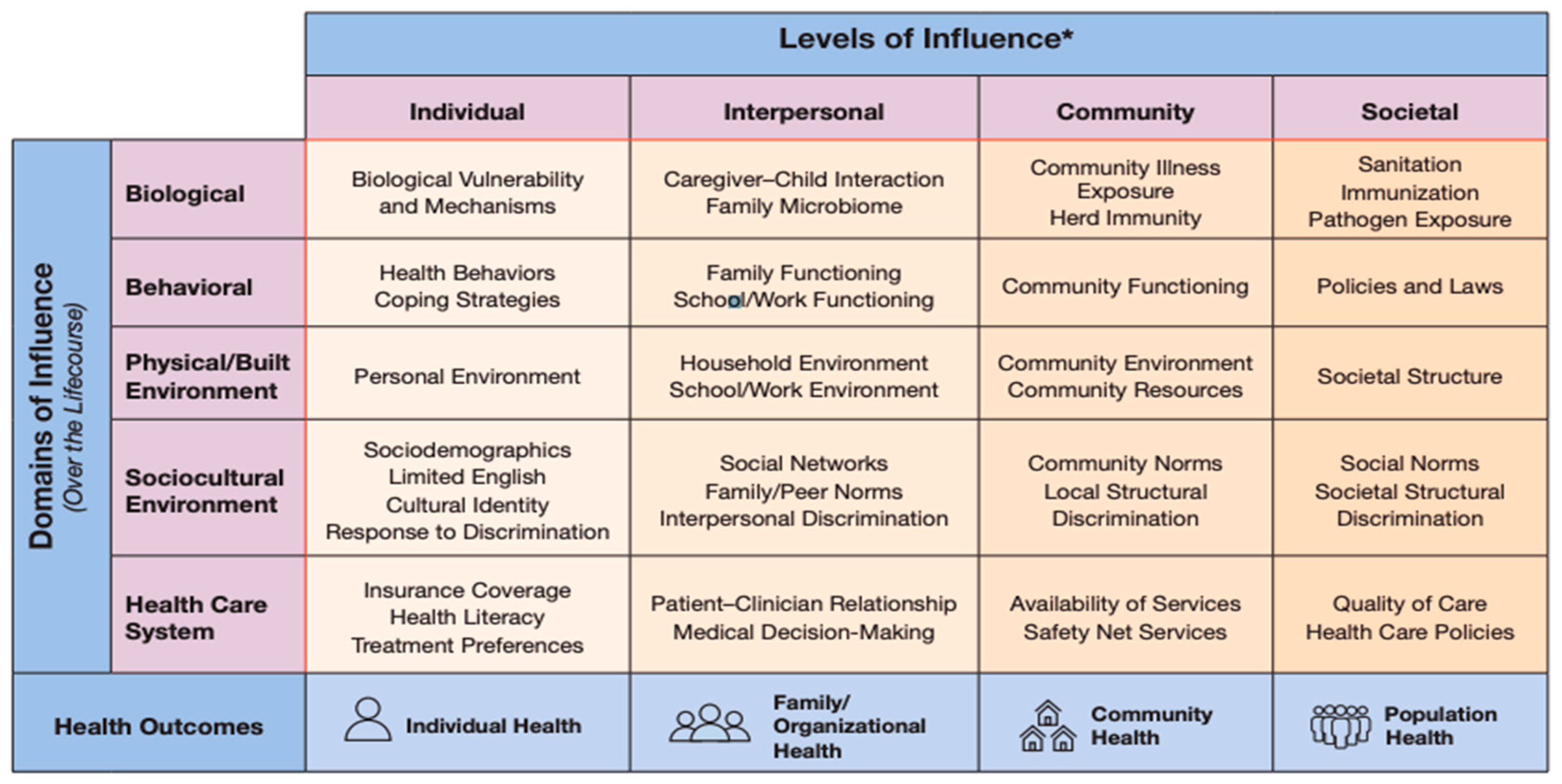

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework. 2017. Available online: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2024-09/nimhdResearchFramework.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Critical Perspectives on Aging: The Political and Moral Economy of Growing Old; Baywood Publishing Company: Amityville, NY, USA, 1991.

- Estes, C.L. Social Policy & Aging: A Critical Perspective; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky, M.R.; Sankar, A. Extending the critical gerontology perspective: Cultural dimensions. Introduction. Gerontologist 1993, 33, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vespa, J.; Ebglberg, J.; He, W. Old Housing, New Needs: Are U.S. Homes Ready for an Aging Population? In Current Population Reports; U.S. Department of Human Services, U.S. Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mah, J.C.; Stevens, S.J.; Keefe, J.M.; Rockwood, K.; Andrew, M.K. Social factors influencing utilization of home care in community-dwelling older adults: A scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racial Differences in Economic Security: Housing; U.S. Department of the Treasury: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Goodman, N.; Morris, M.; Boston, K. Financial Inequality: Disability, Race and Poverty in America; National Disability Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, A.B. The Epidemiology and Societal Impact of Aging-Related Functional Limitations: A Looming Public Health Crisis. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2023, 78 (Suppl. S1), 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accessibility in Housing: Findings from the 2019 American Housing Survey; Report prepared by SP Group LLC; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; Office of Policy and Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Vij, S.B. Aging in Place: Key Occupational Therapy Collaborators. Open J. Occup. Ther. 2023, 11, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, N.; Shinkle, D.; Lynott, J.; Fox-Grange, W.; Harrell, R. Aging in Place: A state Survey of Livability Policies and Practices; AARP Public Policy Institute, National Conference of State Legislatures: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Levchenko, Y. Enabling Aging in Place: The Impact of Home Modifications on Nursing Home Admission Risk. Innov. Aging 2023, 7 (Suppl. S1), 1153–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finding Innovative Approaches to Support Productive Aging. Available online: https://www.aota.org/practice/clinical-topics/driving-community-mobility/productive-aging (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Smallfield, S.; Elliott, S.J. Occupational Therapy Interventions for Productive Aging Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74, 7401390010p1–7401390010p5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheth, S.; Cogle, C.R. Home Modifications for Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2023, 42, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AARP. Does Medicare Cover Home Safety Equipment? AARP: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman, J.M.; Stamper, D.S.; Sheridan, E.; Caterino, J.M.; Quatman-Yates, C.C.; Quatman, C.E. Barriers to the Initiation of Home Modifications for Older Adults for Fall Prevention. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2021, 12, 21514593211002161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Your Home Checklist for Aging in Place. Available online: https://www.aarp.org/home-family/your-home/info-2021/aging-in-place-checklist.html (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Quarterly Residential Vacancies and Homeownership, First Quarter 2021; Bureau USC: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Ray, R.; Perry, A.M.; Harshbarger, D.; Elizondo, S.; Gibbons, A. Homeownership, Racial Segregation and Policy Solutions to Racial Wealth Equity; The Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fenelon, A.; Mawhorter, S. Housing Affordability and Security Issues Facing Older Adults in the United States. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2021, 31, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, A.M. Know Your Price: Valuing Black Lives and Property in America’s Black Cities; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grasso, A.Y.; Murphy, A.; Abbott-Gaffney, C. The Impact of a Two-Visit Occupational Therapy Home Modification Model on Low-Income Older Adults. Open J. Occup. Ther. 2023, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About Us: Strategic Framework. Available online: https://rebuildingtogether.org/about-us (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Richmond has the Second Highest Eviction Rate in America, Why? In Eviction Crisis; Housing Opportunities Made Equal of Virginia: Richmond, VA, USA, 2020.

- Benjamin, T.; Howell, K. Eviction and Segmented Housing Markets in Richmond, Virginia. HousingPolicy Debate 2020, 31, 627–646. [Google Scholar]

- National Eviction Map. Available online: https://evictionlab.org/map/?m=modeled&c=p&b=efr&s=all&r=counties&y=2018&lang=en (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Boop, C.; Cahill, S.M.; Davis, C.; Dorsey, J.; Gibbs, V.; Herr, B.; Kearney, K.; Lannigan, E.L.G.; Metzger, L.; Miller, J.; et al. Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process—Fourth Edition. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74 (Suppl. S2), 7412410010p1–7412410010p87. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, B.P.; Lu, J.; Tiu, G.F.; Thiamwong, L.; Zhong, Y. Bathroom modifications among community-dwelling older adults who experience falls in the United States: A cross-sectional study. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; Schulz, A.J.; Israel, B.A.; Rice, K.; Martenies, S.E.; Markarian, E. A conceptual framework for evaluating health equity promotion within community-based participatory research partnerships. Eval. Program Plan. 2018, 70, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinsky, J.; Airgood-Obrycki, W.; Harrell, R.; Shannon, G. Which Older Adults Have Access to America’s Most Livable Neighborhoods? An Analysis of AARP’s Livability Index; AARP Public Policy Institute Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Level of Influence | Clinical Aging in Place Intervention | Rebuilding Together Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | Provide advice and assessment on mobility (deficit focused) | Not fully addressed |

| Interpersonal | Provides modifications related to health condition or safety in health concern (deficit focused) | Provide modification or repairs not directly associated with health condition/enhancement (environmental). Not contingent on health condition/not limited to deficits. |

| Community | Not addressed | Relieve the economic burden by providing no-cost repairs. Expand the availability of repairs, combatting displacement/reducing displacement/institutionalization. |

| Societal | Not addressed | Improve neighborhood livability, improve home values in census blocks. Expand AIP to new populations. |

| Attic | Bathroom | Hall | Kitchen | Porch/Deck Railway | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aging in Place Over 64 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| Aging with a Disability Over 64 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Living with a Disability Under 65 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| All Others | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Bed Room | Crawl | Dining Room | Electrical | EXT Door | Fence | Gutters | HVAC | Landscape | Paint | Pests | MISC | Ramp | Roof | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aging in Place Over 64 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| Aging with a Disability Over 64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Living with a Disability Under 65 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| All Others | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Mean Structural | Total Structural | Mean Occupational | Total Occupational | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aging in Place Over 64 | 2.76 | 47 | 0.94 | 16 | 17 (36.17) |

| Aging with a Disability Over 64 | 0.42 | 3 | 0.42 | 3 | 7 (14.89) |

| Living with a Disability Under 65 | 2.8 | 14 | 0.8 | 4 | 5 (10.63) |

| All Others | 2.05 | 37 | 0.61 | 11 | 18 (38.29) |

| Total | 2.14 | 101 | 0.72 | 34 | 47 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rhodes, A.; McNichols, C.C. Aging in Place and Healthcare Equity: Using Community Partnerships to Influence Health Outcomes. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101132

Rhodes A, McNichols CC. Aging in Place and Healthcare Equity: Using Community Partnerships to Influence Health Outcomes. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101132

Chicago/Turabian StyleRhodes, Annie, and Christine C. McNichols. 2025. "Aging in Place and Healthcare Equity: Using Community Partnerships to Influence Health Outcomes" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101132

APA StyleRhodes, A., & McNichols, C. C. (2025). Aging in Place and Healthcare Equity: Using Community Partnerships to Influence Health Outcomes. Healthcare, 13(10), 1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101132