A Qualitative Preliminary Study on the Secondary Trauma Experiences of Individuals Participating in Search and Rescue Activities After an Earthquake

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Trauma

1.2. Secondary Trauma

1.3. Post-Traumatic Growth (PTG)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

- (1)

- Participation in search and rescue operations for at least 3 days after the earthquakes;

- (2)

- Active duty in the debris area;

- (3)

- Staying in the operation area for at least 5 days.

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Evaluation

2.5. Validity and Reliability of Research Data

2.6. Ethical Compliance

3. Results

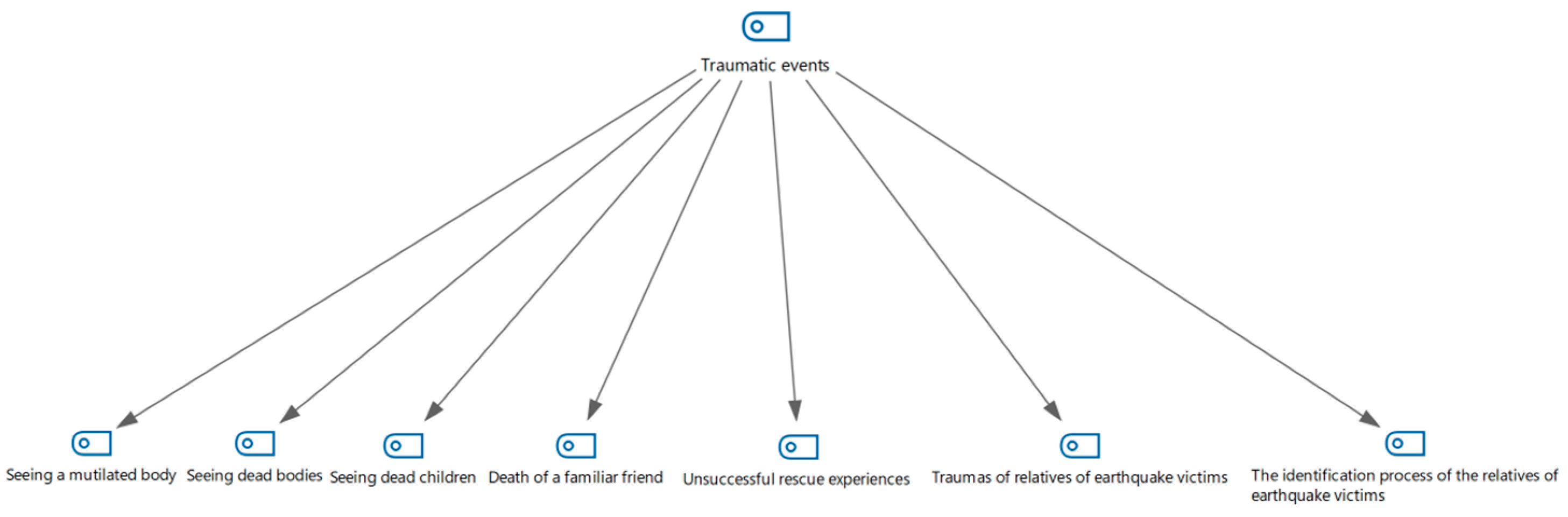

3.1. Characteristics of Trauma

3.1.1. Seeing a Mutilated Body

“Their faces were unrecognizable because concrete had fallen on their faces. A lot of wounds, or a crushed image. It is extremely bad.”P4

“The debris had smashed them all.”P6

3.1.2. Seeing Dead Bodies

“I looked up and there were dead bodies all along the pavements. It’s a screaming pandemonium. The pavements are full of corpses. The bodies were open so that anyone who could identify them could see them.”P6

“The bodies were on top of one another… “The bodies were maybe 10, 15 on top of one another. In front of every building. Ambulances would not be able to pick up the bodies. The corpses remain and of course they stink. People would come, naturally, and it was painful to see their reactions when they saw the corpses days later. I was very affected when I saw those people.”P8

3.1.3. Seeing Dead Children

“There were 33 children. None of the children’s bodies were recovered whole. The debris smashed them all. X child was the one who affected me the most. The debris collapsed and rubble fell right in the middle of the bed, his head was severed, and he had six parts. Only the leg part came out. They scraped the top part of his head with a shovel. The pieces were put in a bucket or something.”P6

“There was a girl dressed in pink. She didn’t belong to our group. And I always wondered what the fate of that girl child was. The fact that we could not take care of it. The state of that girl. She has no mother, no father. Her lifeless body is lying there. It made me very sad that we couldn’t take care of her. I felt like we couldn’t take care of her. So, it stayed like that. They took her away. Who took her? We never knew where they took it. I think there must have been many similar incidents.”P2

3.1.4. Death of a Familiar Friend

“Many of them were my friends. I saw all the deaths. I had a friend who was under the rubble with his child. When I found my friend, I didn’t recognize him. It was very strange, I found him on the fifth day, but I didn’t recognize him.”P1

“I knew most of the people there, which was very difficult. My friends, their children, my nephews. It is very difficult. Very.”P7

3.1.5. Unsuccessful Rescue Experiences

“People from the next building. I heard people there. They shouted there for two days and died. Crying and shouting, but I can’t do anything. You can’t reach them. Everyone was like this.”P1

“The 12–13-story building collapsed in such a way that there were people in the basement, on the first and second floors. There is a shouting sound from below. 15–20 people shouting. They surrounded the place. They couldn’t save those people. It was very bad to watch it.”P8

3.1.6. Traumas of Relatives of Earthquake Victims

“I saw a man whose father was trapped by a column. He was diabetic. They fed him with a straw for 3 days. They gave him his medication. We heard him saying, “Save me, save me, save me, save me. He ate and drank for 3 days. But the man died. No one could do anything.”P8

3.1.7. The Identification Process of the Relatives of Earthquake Victims

“A family looked at the face of their child. He said, “This looks like my son, let me see his t-shirt. His hair is like this. I didn’t recognize him, let me look at his hands. This is my son.” He started kissing his son on the wrapped three-day-old corpse.”P3

“They took the child out and started to say out loud what was on her. A 14-year-old girl has something red on her. He was saying that the family matching this description should come and identify her. But it was not like to be identified.”P5

3.2. Findings on the Theme of Secondary Trauma Symptoms

3.2.1. Impaired Functionality

Sleep Problems

“I have ongoing sleep problems from time to time. Not as often as before, but I still wake up from time to time.”P4

“I was sleepless for a while.”P5

Concentration Problems

“I’m shattered because of lack of sleep. I couldn’t devote myself to my work, I couldn’t devote myself to my family and friends. I had a concentration disorder.”P7

Anger

“I had an aggression problem for the first two months. I had an anger problem. I used to snap too much on unnecessary things. It passed in time. I was angry with people. People who knew me understood me. It made me a sharp, aggressive, and emotional person.”P6

3.2.2. Arousal

“When I go somewhere, for example, I am here today, I started to think automatically if there is an earthquake at any moment, how can I get out of here, where is the door, where would it be better to get out, what floor am I on.”P7

3.2.3. Avoidance

“I pretended it didn’t happen. I said you’ll have a healthier life if you shut it down. I felt like I would collapse if I got into it. That’s why I didn’t want to meet with the families or anything else. We never talked to my friend who went. He doesn’t bring it up and I don’t bring it up. That mission is behind us. Life goes on. And as soon as I arrived, I started to take care of many different things at work. I tried to distract myself with them. After I came back from there, I didn’t read a single news item about this issue. I didn’t contact them. I didn’t listen to their stories. I pretended they didn’t exist.”P5

3.2.4. Reliving the Moment

“After the earthquake, especially in the first month, I got up a lot, jumping out of bed, wondering if an earthquake was happening? When I felt the slightest shaking, I wondered if an earthquake was happening. I still do?” I still haven’t deleted the photos. For example, I look at them from time to time. When I read anything about the earthquake, I look at those photos as they come to my mind. These photos remind me of what I told you. The beds, deaths, corpses, the state of the people where I was charging my phone reminds me of that mosque and many other things. Being there is not something easy to cope with.”P4

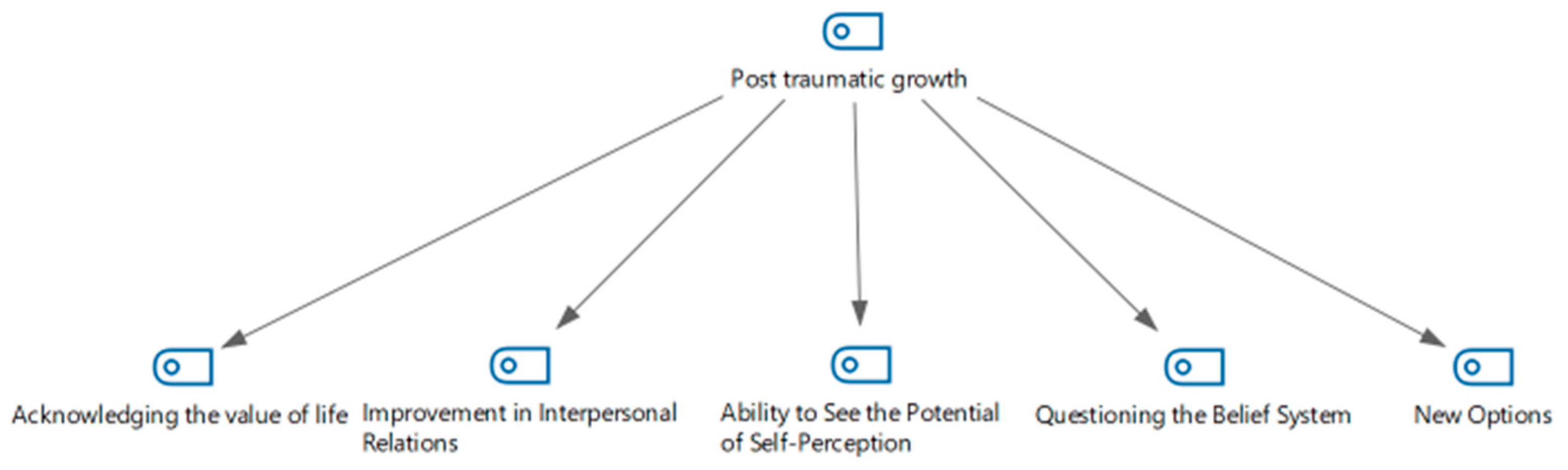

3.3. Findings on the Theme of Post-Traumatic Growth

3.3.1. Acknowledging the Value of Life

“I realized that life could end at any moment, that it is only a moment, that it is not in your or anyone else’s hands. I realized that life is short, that it can end in a minute. I learnt not to be sad at the point of living life. I am grateful. I was aware of death, but I realized it more.”P1

“It reinforced my thoughts. Since I know that there will be death in life, I try to pursue whatever will give me happiness in my life. I am after spirituality; my profession has been a great binding at this point. I think even a study can be conducted on this.”P2

3.3.2. Improvement in Interpersonal Relations

“It was a turning point for me. I decided to leave that day. The pain of some people was my turning point. Yes, I did not want such a thing to happen, but after it happened, I thought that I should move forward as much as I can help them and as much as I can help myself.”P3

“I started to be more sincere in my friendships. When you are frank and honest, you realize that you have nothing to lose. I don’t get into small-scale arguments anymore. Then I realized the value of family and friends more.”P6

3.3.3. Ability to See Self-Potential

“I grew up, I had no experience, now I have experience. It was a wild and horrible environment there. I allowed the events that happened to change me. I will never forget what I witnessed in Adıyaman throughout my life. I think it had a very positive contribution. I realized that I should work in a better institution.”P6

“After seeing them, I realized that I am really stronger, and I have to go on with life.”P5

3.3.4. Questioning Belief Systems

“I also lost some of my beliefs. After digging up all those dead children. I questioned my religious beliefs. Why would a child die in his bed? What sin did he commit that he died in his bed? I questioned what sins young people have committed.”P1 Nurse

3.3.5. New Options

“With most of the photographs I received awards and I have been offered jobs. It was to improve myself. I would consider leaving the organization that I am currently working for because I am not satisfied with the team.”P6

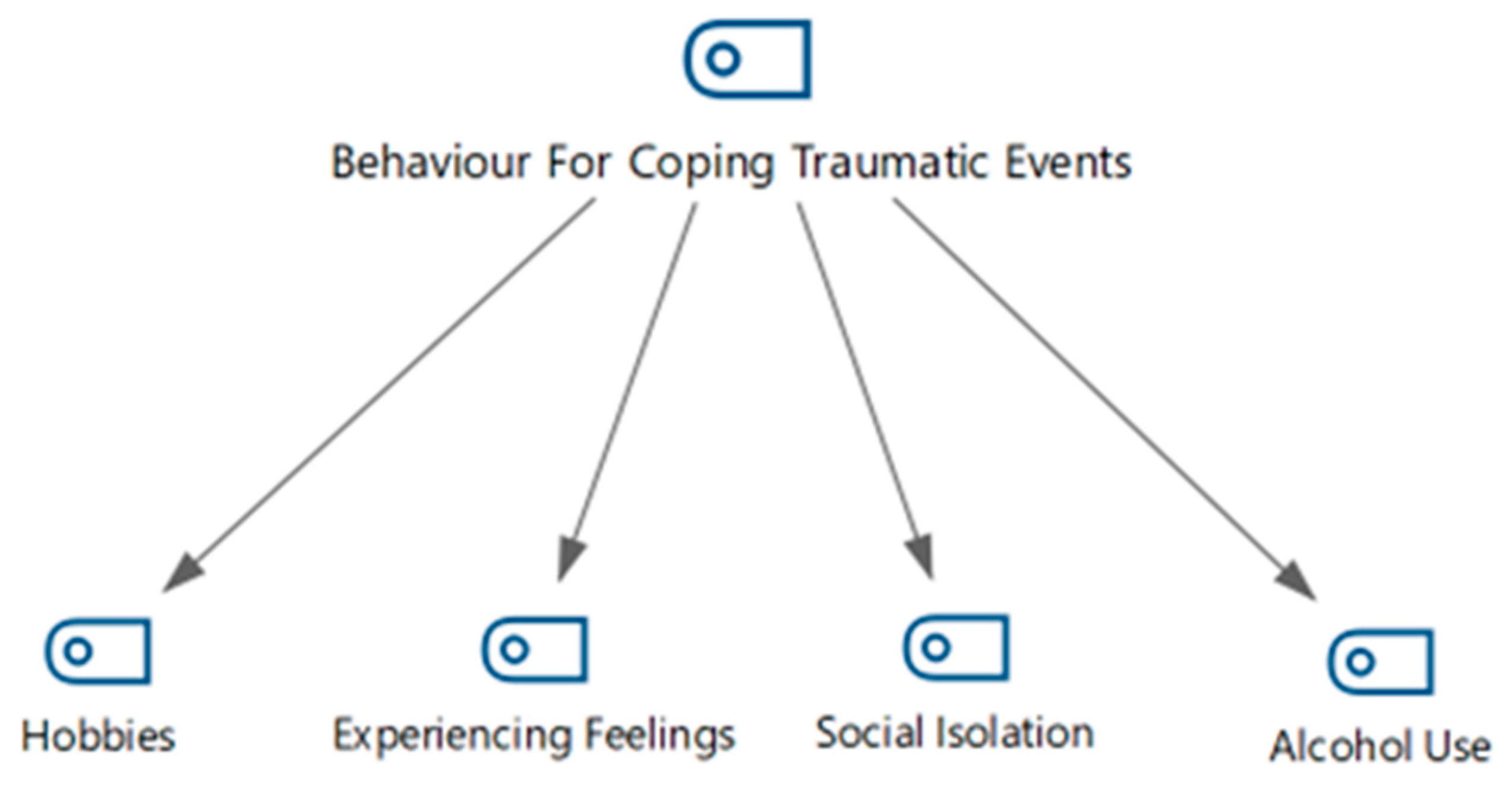

3.4. Behaviors for Coping with Traumatic Events

3.4.1. Hobbies

“I brought music into my life. Music is one of the reasons to hold on to life. Seeing a place, being in different places, getting to know different cultures.”P4

3.4.2. Feeling Emotions

“I said OK, I turned my head and left. I left crying.”P1

“Then I said, “Feel your emotions, if you need tears in your eyes, let them flow. Then do your job.”P2

3.4.3. Social Isolation

“I didn’t see anyone for 15 days. I didn’t see my mum, dad, or son.”P1

“I tried to live within myself.”P2

3.4.4. Alcohol Use

“I’ve been drinking alcohol. Actually recently.”P7

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenging Conditions

4.2. Traumatic Events

4.3. Secondary Trauma Symptoms

4.4. Post-Traumatic Growth

4.5. Coping with Traumatic Events

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UNICEF | United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund |

| AFAD | Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency |

| APA | American Psychiatric Association |

| PTG | Post-traumatic growth |

| TRNC | Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus |

Appendix A. Combined Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ)

| Area 1: Research Team and Reflexivity | |||

| Personal Characteristics | |||

| Number | Item | Guiding Questions | Explanations |

| 1 | Interviewer/facilitator | Which author/authors conducted the interview or focus group? | The first author conducted the interview. |

| 2 | Credentials | What were the credentials of the researcher? | First author PhD Second author Prof. Dr. Third author Asst. Prof. |

| 3 | Profession | Professions of researchers? | First author, Clinical Psychology Doctoral Student Second author, Doctor of Psychiatry Third author, Lecturer |

| 4 | Gender | Gender of researchers? | Three female researchers. |

| 5 | Experience and training | What experience or training did the researcher have? | The first author has taken qualitative courses and has experience in qualitative research. The second author has taken qualitative courses and has published qualitative studies in international journals. The third author has taken qualitative courses. |

| Relationship with Participants | |||

| 6 | Relationship status | Was a relationship established before the training started? | The first author is a PhD student. The second author is the PhD thesis advisor of the PhD student. The third author is the student’s co-supervisor at the doctoral thesis stage. |

| 7 | Interviewer’s participant knowledge | What did the participants know about the researcher, e.g., personal goals and reasons for conducting research? | The participants did not have collegial relationships with the research team members or interviewers. Participants were informed about the study and the reason for the study before the interviews. |

| 8 | Interviewer characteristics | What characteristics were reported about the interviewer/facilitator? | All three researchers are interested in secondary traumatic stress. The first researcher is a student at the university. The second researcher is a lecturer at the same university as the first researcher and the third researcher is a lecturer at another university. |

| Area 2. Study Design | |||

| Theoretical Framework | |||

| 9 | Methodological Orientation and Theory | Which methodological orientation was specified to support the study? | This was a qualitative study. |

| Participant Selection | |||

| 10 | Sampling | How were participants selected? | Eight participants were reached using the snowball technique. This method is particularly effective for reaching hidden or difficult-to-access populations, as it enables participant recruitment through a chain of referrals [35]. |

| 11 | Approach method | How were participants approached? | The timing of the interviews was determined by the individuals who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study. |

| 12 | Sample size | How many participants were there in the study? | A total of 8 individuals were included in the study. |

| 13 | Disagree | How many people refused to participate or dropped out? | No individuals declined to participate in the study. |

| Setting | |||

| 14 | The setting of data collection | Where was the data collected? | Detailed information is provided in the data collection section of this study. The interviews took place in the therapy room of the first author’s clinic. |

| 15 | Presence of non-participants | Was there anyone else present apart from the participants and the researchers? | There were no observers. |

| 16 | Description of the sample | What are the important characteristics of the sample? | Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 18 nurses working in a psychiatric hospital in a province in the north of the country. Interviews were conducted with 18 nurses who worked as psychiatric nurses, providing care in a psychiatric clinic for people who had experienced psychological trauma, and were open to communication and voluntarily participated in the study. The mean age of the individuals included in the study was 35.44 ± 7.70. Thirteen of the participants were female, and twelve were married. The nurses’ mean years of professional experience were 11.05 ± 7.84, and the mean years of working as a psychiatric nurse were 6.44 ± 5.36. |

| Data Collection | |||

| 17 | Interview guide | Did the authors provide questions, prompts, and guidelines? Has the study been pilot-tested? | Detailed information is provided in the Methods section. |

| 18 | Repeat interviews | Have there been any re-interviews? If yes, how many? | No. |

| 19 | Audio/visual recording | Was audio or visual recording used to collect data in the study? | Interviews were recorded with a voice recorder. |

| 20 | Field notes | Were field notes taken during or after the interview or during the focus group? | Responses of all individuals and the researcher were recorded. |

| 21 | Duration | How long were the interviews or focus groups? | Each interview lasted between 45 and 50 min. |

| 22 | Data saturation | Has data saturation been discussed? | Data saturation was discussed. |

| 23 | Transcripts returned | Have transcripts been returned to participants for comments and corrections? | No. |

| Area 3: Analysis and Findings | |||

| 24 | Number of data coders | How many data coders coded the data? | Two researchers and a third individual coded the data. |

| 25 | Description of the coding tree | Did the authors describe the coding tree? | The titles and subtitles in the results section represent the final coding tree. |

| 26 | Derivation of themes | Were the themes predetermined or derived from the data? | Themes were derived from the data. |

| 27 | Software | What software, if any, was used to manage the data? | MAXQDA Analytical Pro 2020 was used to analyze the research data. |

| 28 | Participant control | Did participants provide feedback on the findings? | Yes |

| Reporting | |||

| 29 | Quotes provided | Are participant quotes presented to illustrate themes/findings? Is each quote identified? | Yes Yes |

| 30 | Data and findings consistent | Was there consistency between the data presented and the findings? | Yes |

| 31 | Clarity of main themes | Are the main themes presented in the findings? | Yes |

| 32 | Clarity of small themes | Is there an explanation of the different cases or a discussion of minor issues? | Yes |

Appendix B

Appendix C. Informed Consent Form

Appendix D. Semi-Structured Interview Form

- (1)

- Age

- (2)

- Nationality

- (a)

- TRNC

- (b)

- Turkish

- (c)

- TRNC-Turkish

- (d)

- Other

- (3)

- Gender

- (a)

- Female

- (b)

- Male

- (4)

- Marital Status?

- (a)

- Married

- (b)

- Single

- (c)

- In a relationship

- (d)

- Divorced

- (e)

- Widowed

- (5)

- Do you have children? If yes, please indicate the number

- (a)

- yes

- (b)

- no

- (6)

- Did you receive psychological support at any point in your life before participating in search and rescue operations (psychologist, psychiatric interview, medication, etc.)?

- (7)

- Have you ever intervened in or witnessed traumatizing events (witnessing death, seeing severely injured, dismembered face, body, etc.) before participating in search and rescue operations? If yes, could you briefly tell us about this event?

- (8)

- Did you receive training (disaster, first aid, etc.) before participating in search and rescue activities?

- (1)

- How did you decide to participate in search and rescue operations? Which region did you go to and how many days did you stay?

- (2)

- Have you ever intervened in or witnessed traumatizing events (witnessing death, seeing severely injured, dismembered face, body, etc.) after participating in search and rescue operations? If yes, could you briefly tell us about this event or events?

- (3)

- Have you attended any training (disaster, first aid, etc.) after search and rescue operations?

- (4)

- Which conditions challenged you during the search and rescue operations?

- (5)

- What traumatic event or events have affected you at the most while you participated to participation in search and rescue operations?

- (1)

- How does the traumatic events that you have experienced in search and rescue operations now affect your quality of life?

- (2)

- Did you receive support (professional, family, friends, etc.) after the search and rescue operations? How?

- (3)

- How did the traumatic events you experienced during search and rescue operations affect your relationship with your spouse, children, and close friends.

- (4)

- How did you cope with the aftermath of the search and rescue operations?

References

- Farokhzadian, J.; Shahrbabaki, P.M.; Farahmandnia, H.; Eskici, G.T.; Goki, F.S. Exploring the consequences of nurses’ involvement in disaster response: Findings from a qualitative content analysis study. BMC Emerg. Med. 2024, 24, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.F.; Jian, Y.S.; Yang, C.Y. Cumulative exposure to citizens’ trauma and secondary traumatic stress among police officers: The role of specialization in domestic violence prevention. Police Pract. Res. 2024, 25, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, Y.; Goto, T.; Shelby, J.; Oshio, A.; Nishi, D.; Takahashi, S. Secondary trauma and posttraumatic growth among mental health clinicians involved in disaster relief activities following the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2020, 33, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscarino, J.A.; Figley, C.R.; Adams, R.E. Compassion fatigue following the September 11 terrorist attacks: A study of secondary trauma among New York City social workers. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Health 2004, 6, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Cansel, N.; Ucuz, İ. Post-traumatic stress and associated factors among healthcare workers in the early stage following the 2020 Malatya-Elazığ earthquake. Konuralp Med. J. 2020, 14, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Taormina, R.J. Reduced secondary trauma among Chinese earthquake rescuers: A test of correlates and life indicators. J. Loss Trauma 2011, 16, 542–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetinkaya Özdemir, S.; Semerci Çakmak, V.; Ziyai, N.Y.; Çakir, E. Experiences of intensive care nurses providing care to the victims of Kahramanmaraş earthquakes. Nurs. Crit. Care 2023, 29, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güre, M.D.P. How to help the helpers? Integrative group therapy practices with professionals in disasters. J. Soc. Work. 2021, 6, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, B.; Şahin, N.H. Arama-Kurtarma çalışanlarında travma sonrası stres belirtileri ve travma sonrası büyüme. Turkish J. Psychol. 2007, 22, 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dikbaş, Ş.K.; Okanlı, A. Hemşirelerde ikincil travmatik stres ve stresle başa çıkma tarzları arasındaki ilişki. Univ. Health Sci. J. Nurs. 2022, 4, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, M.L. In their words: Secondary traumatic stress in social workers responding to the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York City. Soc. Work 2007, 52, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF İnsani Durum Raporları (Depremler)—1. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/turkiye/en/media/15471/file/UNICEF%20T%C3%BCrkiye%20Humanitarian%20Situation%20Report%20#3%20(Earthquake)%20-%2023%20February-01%20March%202023.pdf%20.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- AFAD. Kahramanmaras’ta Meydana Gelen Depremler Hakkında Basın Bülteni-32. Available online: https://www.afad.gov.tr/kahramanmarasta-meydana-gelen-depremler-hk-basin-bulteni-32 (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- BBC News. Turkey and Syria Earthquake: Bodies Found in Search for Volleyball Team [Internet]. BBC News, 6 February 2023. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-64579269 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Cyprus Mail. Hundreds Gather in Famagusta to Demand Justice for Cypriot Children Killed in Earthquake [Internet]. Cyprus Mail, 30 November 2023. Available online: https://cyprus-mail.com/2023/11/30/hundreds-gather-in-famagusta-to-demand-justice-for-cypriot-children-killed-in-earthquake/ (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Cyprus Mail. Trial Resumes over Cypriot Children Killed in Earthquake [Internet]. Nicosia (CY): Cyprus Mail, 22 October 2024. Available online: https://cyprus-mail.com/2024/10/22/trial-resumes-over-cypriot-children-killed-in-earthquake (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Öztürk, O.; Uluşahin, A. Ruh Sağlığı ve Bozuklukları, 15. Baskı; Nobel Tıp Kitapevleri: Ankara, Turkey, 2018; pp. 380–389. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; DSM-5; Volume 5, No. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Figley, C.R. Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized; Figley, C.R., Ed.; Brunner/Mazel: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Valent, P. Diagnosis and Treatment of Helper Stresses, Traumas, and Illnesses. In Treatıng Compassıon Fatıgue, 1st ed.; Figley, C., Ed.; Brunner Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, C.S.; Ursano, R.J.; Wang, L. Acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in disaster or rescue workers. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bride, B.E.; Robinson, M.M.; Yegidis, B.; Figley, C.R. Development and validation of the secondary traumatic stress scale. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2004, 14, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, S.; Sjattar, E.L.; Seniwati, T. Factors affecting secondary traumatic stress disorder among search and rescue team in Makassar. Indones. Contemp. Nurs. J. (ICON J.) 2021, 5, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topkara, N.; Reyhan, F.A.; Dağlı, E.; Bakır, E. Identifying the relationship between compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress levels among healthcare workers in the earthquake zone. TOGÜ Health Sci. J. 2023, 4, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahernejad, S.; Ghaffari, S.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Wesemann, U.; Farahmandnia, H.; Sahebi, A. Post-traumatic stress disorder in medical workers involved in earthquake response: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureen, N.; Gul, S.; Maqsood, A.; Hakim, H.; Yaswi, A. Navigating the shadows of others’ traumas: An in-depth examination of secondary traumatic stress and psychological distress among rescue professionals. Behav. Sci. 2023, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naturale, A. How do we understand disaster-related vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion fatigue? In Vicarious Trauma and Disaster Mental Health; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 1996, 9, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, S.; Hankin, I.T.; Pratt, J.A.; Hackler, D.R.; Lanman, O.N. Posttraumatic growth in trauma recollections of 9/11 survivors: A narrative approach. J. Loss Trauma 2016, 21, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, N.A.; Arslan, R. Travma sonrası stres ile travma sonrası büyüme arasındaki ilişkide sosyal desteğin ve maneviyatın aracı rolü. Elektron. Sos. Bilim. Derg. 2020, 19, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuhan, J.; Wang, D.C.; Canada, A.; Schwartz, J. Growth after trauma: The role of self-compassion following Hurricane Harvey. Trauma Care 2021, 1, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.; Burkle, F.; Gebbie, K.; Ford, D.; Bensimon, C. A qualitative study of paramedic duty to treat during disaster response. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019, 13, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and İmplementation, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass A Wiley Brand: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative İnquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, C. Sampling knowledge: The hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2008, 11, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Effective Evaluation: İmproving the Usefulness of Evaluation Results Through Responsive and Naturalistic Approaches; Jossey-Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Köse, A. Voluntary search-and-rescue workers’ experiences after witnessing trauma in the earthquake field. OPUS J. Soc. Res. 2023, 20, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouraghaei, M.; Jannati, A.; Moharamzadeh, P.; Ghaffarzad, A.; Far, M.H.; Babaie, J. Challenges of hospital response to the twin earthquakes of August 21, 2012, in East Azerbaijan, Iran. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2017, 11, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, J.; Fitzgerald, G.; Chhetri, M.B.P. Health risks and challenges in earthquake responders in Nepal: A qualitative research. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2019, 34, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slepski, L.A. Emergency preparedness and professional competency among health care providers during hurricanes Katrina and Rita: Pilot study results. Disaster Manag. Response 2007, 5, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köçer, M.S.; Aslan, R. Gönüllü arama kurtarma ekiplerinin orman yangınlarındaki tahliye deneyimleri: 2021 Akdeniz orman yangınları. Afet ve Risk Dergisi 2023, 6, 829–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, E.A. Compassion fatigue in nurses. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2010, 23, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, M.İ.; Başterzi, A.D.; Yıldırım, E.A.; Yüksel, Ş.; Aker, A.T.; Semerci, B.; Hacıoğlu Yıldırım, M. Deprem Sonrası Erken Dönemde Koruyucu ve Tedavi Edici Ruh Sağlığı Hizmeti-Türkiye Psikiyatri Derneği Uzman Görüşü. Turk. J. Psychiatry 2023, 34, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- VanDevanter, N.; Kovner, C.T.; Raveis, V.H.; McCollum, M.; Keller, R. Challenges of nurses’ deployment to other New York City hospitals in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. J. Urban Health 2014, 91, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.; Long, A. Too tired to care? The psychological effects of working with trauma. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2003, 10, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, A.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Najafi, B.; Saidi, H.; Moradi, K. Reflecting on the challenges encountered by nurses at the great Kermanshah earthquake: A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghafinia, M.; Araghizade, H.; Nafissi, N.; Asadollahi, R. Treatment management in disaster: A review of the Bam earthquake experience. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2007, 22, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Li, S.J.; Chen, S.H.; Xie, X.P.; Song, Y.Q.; Jin, Z.H.; Zheng, X.Y. Disaster nursing experiences of Chinese nurses responding to the Sichuan Ya’an earthquake. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2017, 64, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuday, A.D.; Özcan, T.; Çalışkan, C.; Kınık, K. Challenges faced by medical rescue teams during disaster response: A systematic review study. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2023, 17, e548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Soir, E.; Knarren, M.; Zech, E.; Mylle, J.; Kleber, R.; van der Hart, O. A Phenomenological Analysis of Disaster-Related Experiences in Fire and Emergency Medical Services Personnel. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2012, 27, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greinacher, A.; Derezza-Greeven, C.; Herzog, W.; Nikendei, C. Secondary traumatization in first responders: A systematic review. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1562840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zheng, R.; Jacelon, C.S.; McClement, S.; Thompson, G.; Chochinov, H. Dignity of the patient-–family unit: Further understanding in hospice palliative care. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2022, 12, e599–e606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bıçakcı, A.B.; Okumuş, F.E.E. Depremin psikolojik etkileri ve yardım çalışanları. Avrasya Dosyası 2023, 14, 206–236. [Google Scholar]

- Ogińska-Bulik, N.; Michalska, P. Indirect trauma exposure and secondary traumatic stress among professionals: Mediating role of empathy and cognitive trauma processing. Psychiatr. Polska 2024, 58, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, G.; Yurt, E. Evaluation of the situations of coping with mental trauma and trauma in emergency service personnel who medically intervened to earthquake affected people in the 2020 Izmir earthquake. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2024, 18, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, L.M. Trustworthiness in qualitative research. Medsurg Nurs. 2016, 25, 435–436. [Google Scholar]

- Sevim, K.; Öksüz Poplata, S. Kahramanmaraş depremi sonrası gönüllü çalışmalara katılan kişilerin psikolojik dayanıklılık ve ikincil travmatik stres düzeyleri arasındaki ilişki. TYB Akademi 2024, 78–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, X.; Zeng, M.; Wu, X. Post-Traumatic stress symptoms and post-traumatic growth: Evidence from a longitudinal study following an Earthquake Disaster. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; An, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Du, J.; Xu, W. Mindfulness, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and posttraumatic growth in aid workers: The role of self-acceptance and rumination. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2021, 209, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, A.; Bahadır Yılmaz, E.; Altınbaş, A. Comparison of post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic growth status between healthcare professionals employed in earthquake-affected areas and non-employing employees. Forbes J. Med. 2023, 4, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoğlu, E. Çocuğa yönelik cinsel istismar vakaları ile çalışan sosyal çalışmacıların psikososyal etkilenme deneyimleri. Gümüşhane Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilim. Derg. 2017, 6, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Taku, K.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic Growth: Theory, Research, and Applications; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Participant No. | Age | Marital Status | Nationality | Occupation | Rescue Operation Start Date | Working Time (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 42 | Widow | TRNC * | Nurse | 6 February 2023 | 7 |

| P2 | 37 | Single | TRNC | Nurse | 7 February 2023 | 6 |

| P3 | 38 | Married | TRNC | Nurse | 7 February 2023 | 6 |

| P4 | 32 | Single | TRNC and Turkish | Journalist | 7 February 2023 | 7 |

| P5 | 32 | Married | TRNC and Turkish | Journalist | 6 February 2023 | 8 |

| P6 | 24 | Single | TRNC | Journalist | 7 February 2023 | 6 |

| P7 | 45 | Married | TRNC | Volunteer | 7 February 2023 | 4 |

| P8 | 30 | Married | TRNC and Turkish | Volunteer | 9 February 2023 | 10 |

| Conditions | N | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Cold | 8 | 10,000 |

| Toilet | 8 | 10,000 |

| Chaos | 6 | 7500 |

| Accommodation | 6 | 7500 |

| Aftershocks | 5 | 6250 |

| Limited communication | 4 | 5000 |

| Dead body smell | 4 | 5000 |

| Food | 4 | 5000 |

| Lack of medication and supplies | 3 | 3750 |

| Transportation | 3 | 3750 |

| Security (extortion, despoiling) | 2 | 2500 |

| Lack of coordination at the excavation zone | 2 | 2500 |

| Search activity in the same environment with earthquake victims | 2 | 2500 |

| Analyzed documents | 8 | 10,000 |

| Theme | Sub-Theme |

|---|---|

| Traumatic events | Seeing a mutilated body |

| Seeing dead children | |

| Seeing the death of a familiar friend | |

| Not being able to help those who need help | |

| Traumas of relatives of earthquake victims/survivors’ experiences | |

| Process of families identifying their relatives | |

| Symptoms of secondary trauma | Impaired functionality |

| Sleep problems | |

| Concentration problems | |

| Anger problems | |

| Arousal | |

| Avoidance | |

| Living again | |

| Post-traumatic growth | Understanding the value of life |

| Questioning belief systems | |

| Self-perception | |

| Ability to see new options | |

| Improvement in interpersonal relationships | |

| Coping with trauma | Embracing feelings |

| Hobbies | |

| Alcohol use | |

| Social isolation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Çorbacı, E.; Tansel, E.; Alkan, D. A Qualitative Preliminary Study on the Secondary Trauma Experiences of Individuals Participating in Search and Rescue Activities After an Earthquake. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101101

Çorbacı E, Tansel E, Alkan D. A Qualitative Preliminary Study on the Secondary Trauma Experiences of Individuals Participating in Search and Rescue Activities After an Earthquake. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101101

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇorbacı, Ebru, Ebru Tansel, and Damla Alkan. 2025. "A Qualitative Preliminary Study on the Secondary Trauma Experiences of Individuals Participating in Search and Rescue Activities After an Earthquake" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101101

APA StyleÇorbacı, E., Tansel, E., & Alkan, D. (2025). A Qualitative Preliminary Study on the Secondary Trauma Experiences of Individuals Participating in Search and Rescue Activities After an Earthquake. Healthcare, 13(10), 1101. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101101