Using the Trauma Reintegration Process to Treat Posttraumatic Stress Disorder with Dissociation and Somatic Features: A Case Series

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

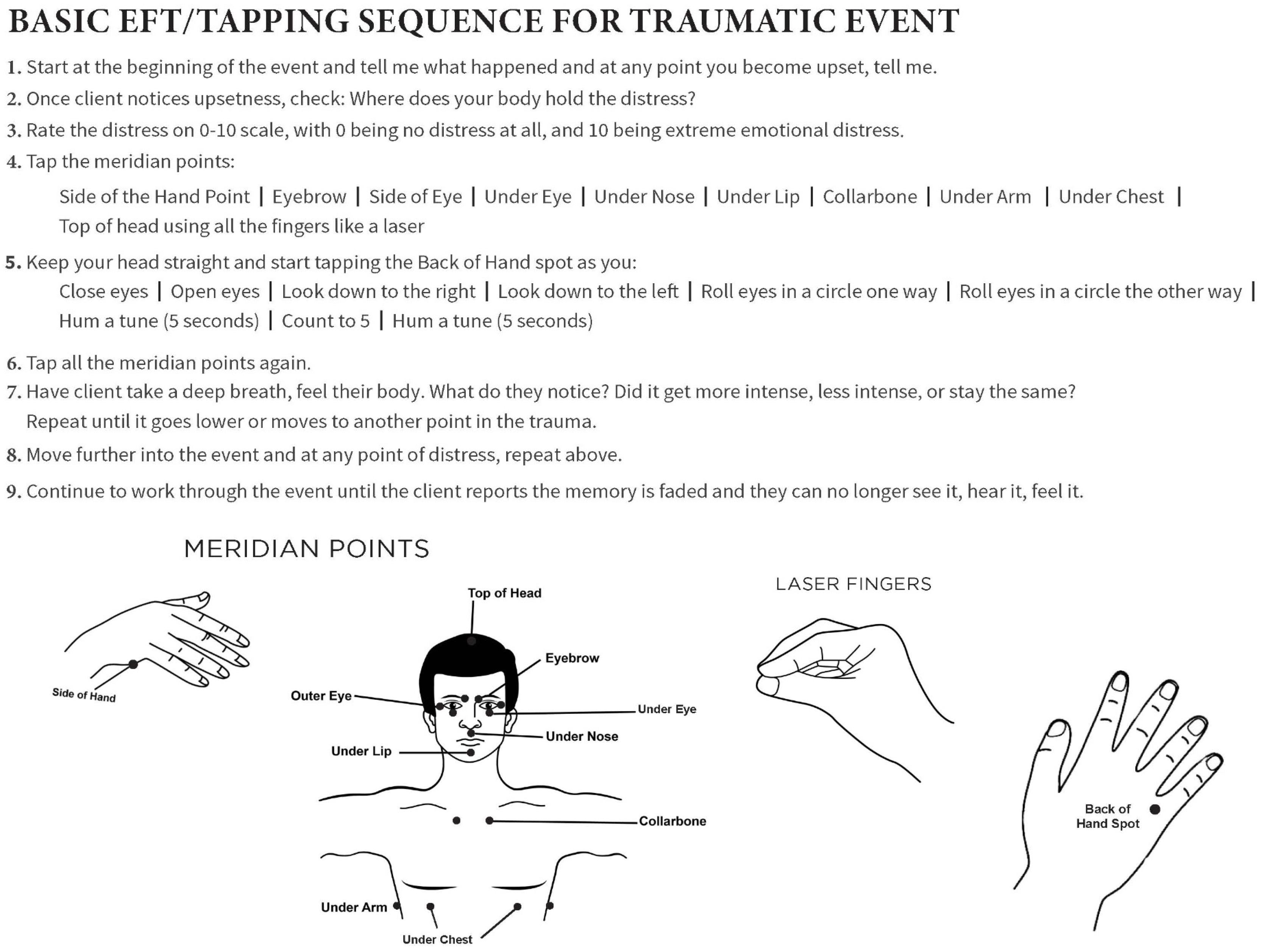

2.1. Emotional Freedom Techniques

2.2. Trauma Reintegration Process

2.3. Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire

2.4. Combining the Methods

3. Results

- Case 1: MVA in a young woman without a trauma history

- I asked, “Where do you see yourself?” L replied she was “outside the car watching herself stuck inside the car”.

- I guided her to imagine the her of today going to the part of her that was outside the car and first comforting her. As she imagined herself approaching the part of her outside the car, she began to feel some anxiety. She imagined herself putting her arms around this aspect of her. As she did this, she began to feel warmth in her body. We did a round of tapping, the SUD level lowered, and she no longer felt disconnected from that part. I then instructed her to move closer to the part of her still in the car and notice what sensations or emotions were happening in her body.

- As she imagined herself returning to the car, she reported that she could now feel herself inside the car feeling frozen and trapped, stating, “My heart is racing and I feel panicked”. We then quickly used EFT to reduce the panic. Once all emotional aspects of the memory had been addressed and the SUD score lowered, I then instructed her to tell herself the truth, that she was freed from the car, that she and her mother had survived the accident, and she was now safe. She did this and repeated EFT. Her body relaxed and her SUD score decreased. The memory became less vivid, the pounding in her chest stopped, and she could experience the next part of the event of being removed from the car by the workers.

- I invited her to bring herself from the MVA forward to the present and to look out her eyes and see today. We used a final round of EFT. She reported a sense of deep physical relief in her body.

- Case 2: MVA in a woman with an extensive trauma history

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- PTSD Alliance. What Is PTSD? 2023. Available online: http://www.ptsdalliance.org/about-ptsd (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Trauma & stress related disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; Text Rev.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L.L.; Schein, J.; Cloutier, M.; Gagnon-Sanschagrin, P.; Maitland, J.; Urganus, A.; Guerin, A.; Lefebvre, P.; Houle, C.R. The economic burden of posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States from a societal perspective. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2022, 83, 40672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). What Is Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)? 2023. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ptsd/what-is-ptsd (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Sartor, Z.; Kelley, L.; Laschober, R. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Evaluation and Treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2023, 107, 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults. 2017. Available online: https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Steenkamp, M.M.; Litz, B.T.; Hoge, C.W.; Marmar, C.R. Psychotherapy for military-related PTSD: A review of randomized clinical trials. JAMA 2015, 314, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, C.; Roberts, N.P.; Gibson, S.; Bisson, J.I. Dropout from psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2020, 11, 1709709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kolk, B.A. The body keeps the score: Memory and the evolving psychobiology of posttraumatic stress. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 1994, 1, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kolk, B.A. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brom, D.; Stokar, Y.; Lawi, C.; Nuriel-Porat, V.; Ziv, Y.; Lerner, K.; Ross, G. Somatic experiencing for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled outcome study. J. Trauma. Stress 2017, 30, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.; Farrell, D.; Barron, I.; Hutchins, J.; Whybrow, D.; Kiernan, M.D. The use of Eye-Movement Desensitization Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy in treating post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic narrative review. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, F. The role of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy in medicine: Addressing the psychological and physical symptoms stemming from adverse life experiences. Perm. J. 2014, 18, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, P.; Kip, K.; Church, D.; Toussaint, L.; Footman, J.; Ballantyne, P.; O'Keefe, T. Emotional freedom techniques for treating post traumatic stress disorder: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1195286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, D. Integrating the manual stimulation of acupuncture points into psychotherapy: A systematic review with clinical recommendations. J. Psychother. Integr. 2023, 33, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.; Feinstein, D. The manual stimulation of acupuncture points in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A review of clinical emotional freedom techniques. Med. Acupunct. 2017, 29, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Church, D.; Stern, S.; Boath, E.; Stewart, A.; Feinstein, D.; Clond, M. Emotional Freedom Techniques to Treat Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Veterans: Review of the Evidence, Survey of Practitioners, and Proposed Clinical Guidelines. Perm. J. 2017, 21, 16–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Church, D. The EFT Manual, 4th ed.; Energy Psychology Press: Petaluma, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, P. The Science Behind Tapping; Hay House: Carlsbad, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan, R. Tapping the Healer Within: Using Thought Field Therapy to Instantly Conquer Your Fears, Anxieties, and Emotional Distress; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, G.; Fowlie, A. Emotional Freedom Techniques: The Manual; Gary Craig: Sea Ranch, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Church, D.; Stapleton, P.; Mollon, P.; Feinstein, D.; Boath, E.; Mackay, D.; Sims, R. Guidelines for the Treatment of PTSD Using Clinical EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques). Healthcare 2018, 6, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leskowitz, E. Integrative medicine for PTSD and TBI: Two innovative approaches. Med. Acupunct. 2016, 28, 81–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.; Stapleton, P.; Vasudevan, A.; O'Keefe, T. Clinical EFT as an evidence-based practice for the treatment of psychological and physiological conditions: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 951451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavranezouli, I.; Megnin-Viggars, O.; Daly, C.; Dias, S.; Stockton, S.; Meiser-Stedman, R.; Trickey, D.; Pilling, S. Research review: Psychological and psychosocial treatments for children and young people with post-traumatic stress disorder: A network meta-analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, D. Uses of energy psychology following catastrophic events. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D. Reductions in pain, depression, and anxiety after PTSD symptom remediation in veterans. Explor. J. Sci. Heal. 2014, 10, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.; Brooks, A.J. CAM and energy psychology techniques remediate PTSD symptoms in veterans and spouses. Explor. J. Sci. Heal. 2014, 10, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronilla, L.; Minewiser, L.; Mollon, P.; McWilliams, M.; Clond, M. EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) remediates PTSD and psychological symptoms in veterans: A randomized controlled replication trial. Energy Psychol. Theory Res. Treat. 2016, 8, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.A.; Mannarino, A.P.; Deblinger, E. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for traumatized children. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 24, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Dissociative disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Dissociative Disorders. 2024. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/dissociative-disorders (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Loewenstein, R.J. Dissociation debates: Everything you know is wrong. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 20, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adverse Childhood Experiences. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/injury-violence-prevention/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/injury/priority/aces.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Feinstein, D. Using energy psychology to remediate emotional wounds rooted in childhood trauma: Preliminary clinical guidelines. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1277555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpe, J. The Practice of Behavior Therapy; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Sise, M.T.; Bender, S.S. The Energy of Belief: Simple Proven Techniques to Release Limiting Beliefs and Transform Your Life, 2nd ed.; Capucia: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre, M.; Karatzias, T.; Ford, J.D. Treatment of complex PTSD. In Effective Treatments for PTSD: Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 3rd ed.; Forbes, D., Bisson, J.L., Monson, C.M., Berliner, L., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 365–384. [Google Scholar]

| Steps for EFT Practitioner | Examples of Client Responses | |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Remember | Ask questions to probe the client’s point of view. | Therapist: Where do you see yourself? What are you noticing? Client: I am outside the car, I am above the car looking down on myself stuck inside the wrecked car. |

| Step 2: Reunite | Guide the client to imagine getting as close as possible to the part of themselves they see still stuck in the trauma. If the SUD score increases, use EFT. Ask the client what they feel, hear, and smell. Guide the client through as many rounds of EFT as needed to reduce SUD score to 3 or less, moving closer and closer to the younger part, explaining and comforting the dissociated self with the truth of how the trauma is now over. | Therapist: Bring the you of today who knows you have been rescued from this accident first to the part outside the car. Use EFT. Comfort her and bring her to the part in the car. What do you see, feel, smell? Client: I can feel the terror now. Therapist guides client to do another round of EFT. Client: I feel calmer now, I see the rescue workers releasing me. I am now outside the car, I am shaking with fear. Therapist guides client through another round of EFT. Therapist: Comfort her and explain how you survived the accident. Client: I survived, I am ok, Mom also survived, I am safe now. Use EFT until SUD score is 3 or less. |

| Step 3: Reintegrate | After the SUD level has lowered to 3, invite the dissociated part (the younger self) to move forward to today and to look out of the client’s eyes in the present day. Repeat EFT with a calming statement until the SUD score is 0. | Therapist: With eyes closed, bring the you from the accident forward to today. When she is ready, invite her to look out your eyes, look around the room and see today. Client: I am ok now, my body is safe. I survived. Use EFT until the SUD score is 0 and the client is fully present. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sise, M.T. Using the Trauma Reintegration Process to Treat Posttraumatic Stress Disorder with Dissociation and Somatic Features: A Case Series. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101092

Sise MT. Using the Trauma Reintegration Process to Treat Posttraumatic Stress Disorder with Dissociation and Somatic Features: A Case Series. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101092

Chicago/Turabian StyleSise, Mary T. 2025. "Using the Trauma Reintegration Process to Treat Posttraumatic Stress Disorder with Dissociation and Somatic Features: A Case Series" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101092

APA StyleSise, M. T. (2025). Using the Trauma Reintegration Process to Treat Posttraumatic Stress Disorder with Dissociation and Somatic Features: A Case Series. Healthcare, 13(10), 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101092