Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms and Its Correlates among Male Medical Students at the University of Bisha, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Procedures of Sampling Collection

2.3. Sampling Technique

2.4. Description of PHQ-9 Instrument

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants

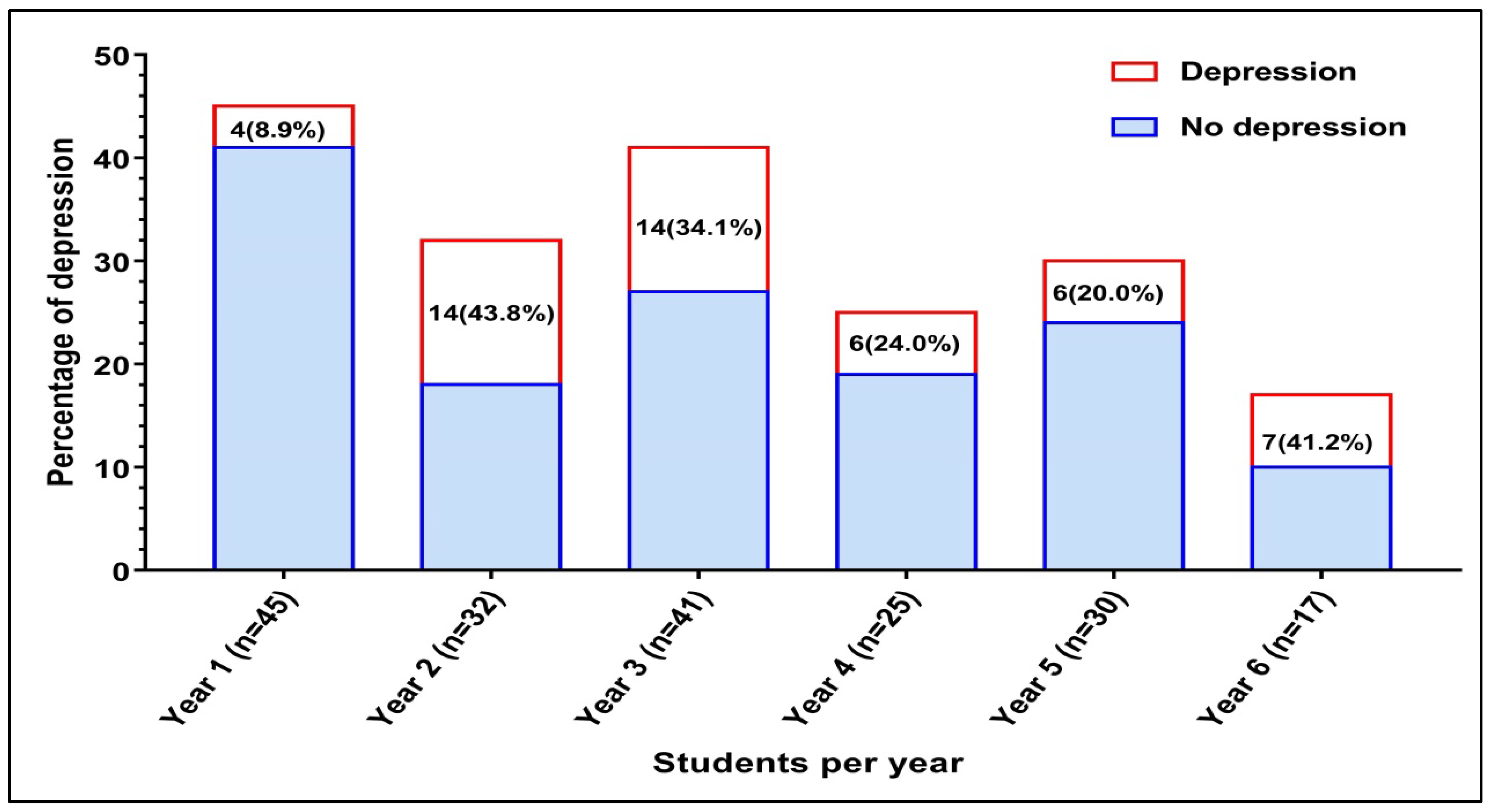

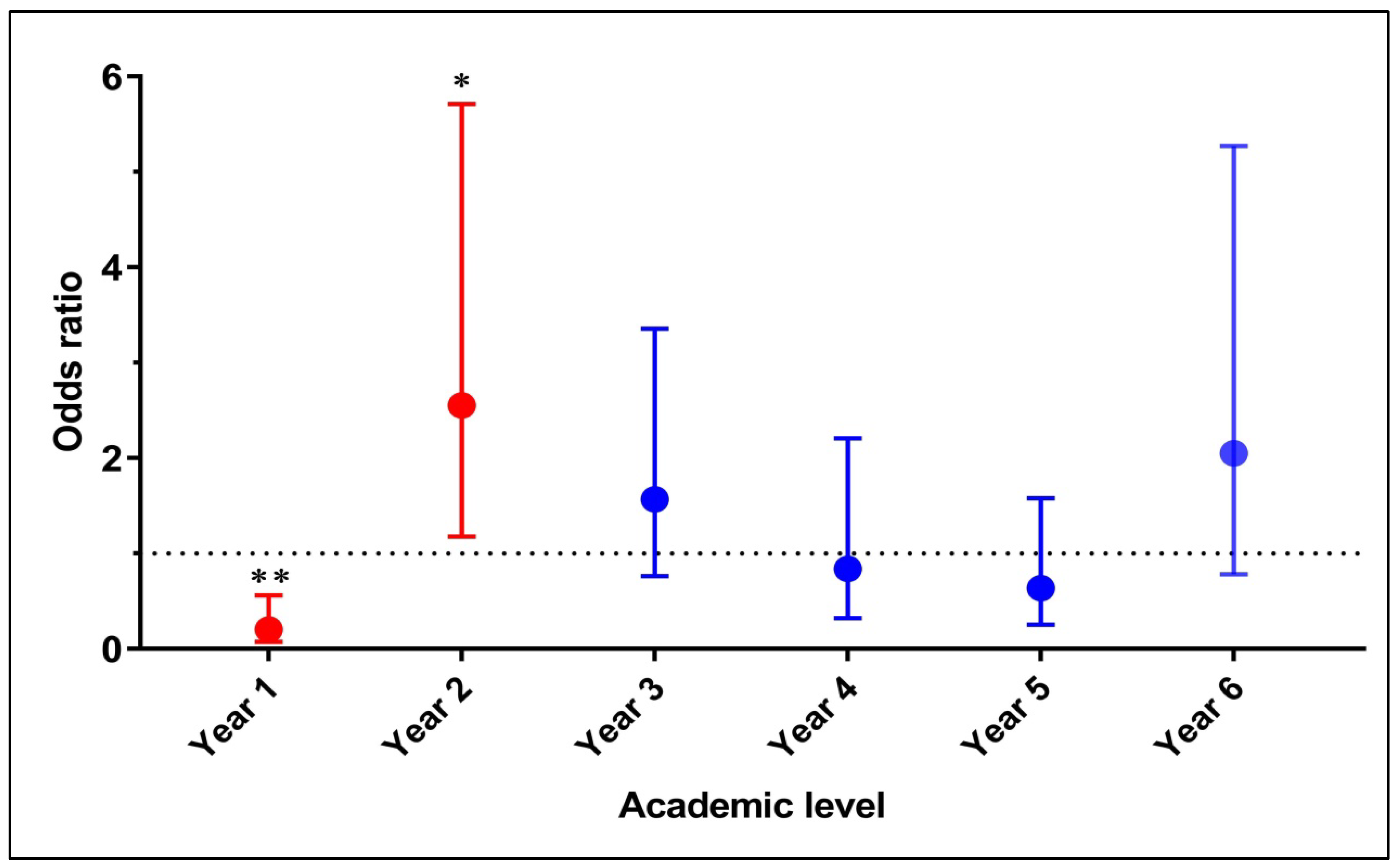

3.2. Prevalence of Depression

3.3. Factors Associated with Depressive Symptoms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Ngasa, S.N.; Sama, C.; Dzekem, B.S.; Nforchu, K.N.; Tindong, M.; Aroke, D.; Dimala, C.A. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Depression among Medical Students in Cameroon: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamasha, A.A.H.; Kareem, Y.M.; Alghamdi, M.S.; Algarni, M.S.; Alahedib, K.S.; Alharbi, F.A. Risk Indicators of Depression among Medical, Dental, Nursing, Pharmacology, and Other Medical Science Students in Saudi Arabia. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2019, 31, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyapong-Opoku, G.; Agyapong, B.; Obuobi-Donkor, G.; Eboreime, E. Depression and Anxiety among Undergraduate Health Science Students: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njim, T.; Mbanga, C.M.; Tindong, M.; Fonkou, S.; Makebe, H.; Toukam, L.; Fondungallah, J.; Fondong, A.; Mulango, I.; Kika, B. Burnout as a Correlate of Depression among Medical Students in Cameroon: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, P.; Hao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; He, L.; et al. The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Mental Problems in Medical Students during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 321, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkot, M.M.; Alnewirah, A.Y.; Bagasi, A.T.; Alshehri, A.A.; Bawazeer, N.A. Depression among Medical versus Non-Medical Students in Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah Al-Mukaramah, Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2017, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.B.; Santos, I.S.; Silveira, P.S.P.; Helena, M.; Lopes, I.; Regina, A.; Dias, N.; Campos, E.P.; Andrade, B.; De Abreu, L.; et al. Factors Associated to Depression and Anxiety in Medical Students: A Multicenter Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthran, R.; Zhang, M.W.B.; Tam, W.W.; Ho, R.C. Prevalence of Depression amongst Medical Students: A Meta-Analysis. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albajjar, M.A.; Bakarman, M.A. Prevalence and Correlates of Depression among Male Medical Students and Interns in Albaha University, Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 1889–1894. [Google Scholar]

- Hakami, R.M. Prevalence of Psychological Distress Among Undergraduate Students at Jazan University: A Cross-Sectional Study. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gilany, A.H.; Amr, M.H.S. Perceived Stress among Male Medical Students in Egypt and Saudi Arabia: Effect of Sociodemographic Factors. Ann. Saudi Med. 2008, 28, 442–448. [Google Scholar]

- Bin Abdulrahman, K.A.; Saleh, F. Steps towards Establishing a New Medical College in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: An Insight into Medical Education in the Kingdom. BMC Med. Educ. 2015, 15, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedaso, A.; Kediro, G.; Yeneabat, T. Factors Associated with Depression among Prisoners in Southern Ethiopia: A Cross-sectional Study. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, N.; Pham, M.V.; Van Pham, H.; Nakamura, H. The Four-Domain Structure Model of a Depression Scale for Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in Haiphong, Vietnam. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanoa, S.; Oluwasina, F.; Shalaby, R.; Kim, E.; Agyapong, B.; Hrabok, M.; Eboreime, E.; Kravtsenyuk, M.; Yang, A.; Nwachukwu, I.; et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Likely Major Depressive Disorder among Medical Students in Alberta, Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhata, N.T.; Ntlantsana, V.; Tomita, A.M.; Mwambene, K.; Saloojee, S. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety and Burnout in Medical Students at the University of Namibia. S. Afr. J. Psychiatry 2023, 29, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleisa, M.A.; Abdullah, N.S.; Alqahtani, A.A.A.; Aleisa, J.A.J.; Algethami, M.R.; Alshahrani, N.Z. Association between Alexithymia and Depression among King Khalid University Medical Students: An Analytical Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bert, F.; Lo Moro, G.; Corradi, A.; Acampora, A.; Agodi, A.; Brunelli, L.; Chironna, M.; Cocchio, S.; Cofini, V.; D’Errico, M.M.; et al. Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms among Italian Medical Students: The Multicentre Cross-Sectional “PRIMES” Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, S.; Stoevesandt, D.; Sapalidis, A.; Rehnisch, C.; Watzke, S. Prevalence and Predictive Factors for Depressive Symptoms among Medical Students in Germany—A Cross-Sectional Study Methods: A Total Number of N = 1103 Medical Students of a Middle-Sized German University Were Sampled and Surveyed Regarding Depressive. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2022, 39, Doc13. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, G.S.; Jain, A.; Hegde, S. Prevalence of Depression and Its Associated Factors Using Beck Depression Inventory among Students of a Medical College in Karnataka. Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 54, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, M.J.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2017, 316, 2214–2236. [Google Scholar]

- Aljadani, A.; Alsolami, A.; Almehmadi, S.; Alhuwaydi, A. Epidemiology of Burnout and Its Association with Academic Performance among Medical Students at Hail University, Saudi Arabia. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2021, 20, e231–e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.E. Team-Based Learning Student Assessment Instrument (TBL-SAI) for Assessing Students’ Acceptance of TBL in a Saudi Medical School. Psychometric Analysis and Differences by Academic Year. Saudi Med. J. 2020, 41, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.E.; Al-Shahrani, A.M.; Abdalla, M.E.; Abubaker, I.M.; Mohamed, M.E. The Effectiveness of Problem-Based Learning in Acquisition of Knowledge, Soft Skills During Basic and Preclinical Sciences: Medical Students’ Points of View. Acta Inform. Med. 2018, 26, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.; Al-Shahrani, A. Implementing of a Problem-Based Learning Strategy in a Saudi Medical School: Requisites and Challenges. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2018, 9, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salih, K.M.; Elnour, S.; Mohammed, N.; Alkhushayl, A.M.; Alghamdi, A.A.; Eljack, I.A.; Al-Faifi, J.; Ibrahim, M.E. Climate of Online E-Learning During COVID-19 Pandemic in a Saudi Medical School: Students’ Perspective. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2023, 10, 238212052311734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khani, A.M.; Sarhandi, M.I.; Zaghloul, M.S.; Ewid, M.; Saquib, N. A Cross-Sectional Survey on Sleep Quality, Mental Health, and Academic Performance among Medical Students in Saudi Arabia. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bahhawi, T.; Albasheer, O.B.; Mohammed, A.; Mohammed, O. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress and Their Association with Khat Use: A Cross-Sectional Study among Jazan University Students, Saudi Arabia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 2755–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Wang, S.; Hsieh, C.R. The Prevalence of Depression and Depressive Symptoms among Adults in China: Estimation Based on a National Household Survey. China Econ. Rev. 2018, 51, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadi, A.N.; Alateeq, D.A.; Al-Sharif, E.; Bawazeer, H.M.; Alanazi, H.; Alshomrani, A.T.; Shuqdar, R.M.; Alowaybil, R. An Arabic Translation, Reliability, and Validation of Patient Health Questionnaire in a Saudi Sample. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2017, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Tanaka, T.; Nakagawa, S.; Nakato, Y.; Kameyama, R.; Boku, S.; Toda, H.; Kurita, T.; Koyama, T. Utility and Limitations of PHQ-9 in a Clinic Specializing in Psychiatric Care. BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beshr, M.S.; Beshr, I.A.; Al-Qubati, H. The Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety among Medical Students in Yemen: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 352, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankar, J.R.; Prabhakaran, A.; Sharma, H. Depression and Stigma in Medical Students at a Private Medical College. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2014, 36, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.; Lee, Y.; Han, C.; Steffens, D.C.; Kim, Y. Usefulness of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for Korean Medical Students. Acad Psychiatry 2014, 38, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahas, A.R.M.F.; Elkalmi, R.M.; Al-Shami, A.M.; Elsayed, T.M. Prevalence of Depression among Health Sciences Students: Findings from a Public University in Malaysia. J. Pharm. Bioallied. Sci. 2019, 11, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, M.; Jeon, H.J.; Kim, H. The Prevalence and Impact of Depression among Medical Students: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study in South Korea. Acad. Med. 2010, 85, 1384–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.K.; Lin, C.; Lin, B.Y.; Chen, D. Medical Students’ Resilience: A Protective Role on Stress and Quality of Life in Clerkship. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Faris, E.A.; Irfan, F.; Van der Vleuten, C.P.M.; Naeem, N.; Alsalem, A.; Alamiri, N.; Alraiyes, T.; Alfowzan, M.; Alabdulsalam, A.; Ababtain, A.; et al. The Prevalence and Correlates of Depressive Symptoms from an Arabian Setting: A Wake up Call. Med. Teach. 2012, 34 (Suppl. S1), S32–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.; Kharboush, D.A.-; El-khatib, L.; Al, A.; Asali, D. Prevalence and Predictors of Anxiety and Depression among Female Medical Students in King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Iran. J. Public Health 2013, 42, 726–736. [Google Scholar]

- Goebert, D.; Thompson, D.; Takeshita, J.; Beach, C.; Bryson, P.; Ephgrave, K.; Kent, A.; Kunkel, M.; Schechter, J.; Tate, J. Depressive Symptoms in Medical Students and Residents: A Multischool Study. Acad. Med. 2009, 84, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.; Banu, P.R.; Thomas, S.; Vardhan, R.V.; Rao, P.T.; Khawaja, N. Depression among Indian University Students and Its Association with Perceived University Academic Environment, Living Arrangements and Personal Issues. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2016, 23, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azim, S.R.; Baig, M. Frequency and Perceived Causes of Depression, Anxiety and Stress among Medical Students of a Private Medical Institute in Karachi: A Mixed Method Study. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2017, 69, 840–845. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, N.; Singh, S.; Gautam, S.; Dhaliwal, U. Motivation and Preparedness of First Semester Medical Students for a Career in Medicine. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2013, 57, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sidana, S.; Kishore, J.; Ghosh, V.; Gulati, D.; Jiloha, R.C.; Anand, T. Prevalence of Depression in Students of a Medical College in New Delhi: A Cross-Sectional Study. Australas. Med. J. 2012, 5, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, A.; Rehman, A.; Malik, A.; Muhammad, U.; Khan, S.; Mahmood, N. Association of Ego Defense Mechanisms with Academic Performance, Anxiety and Depression in Medical Students: A Mixed Methods Study. Cureus 2015, 7, e337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.M.D.E.; Moreira, C.A.; Telles-Correia, D. Anxiety, Depression and Academic Performance: A Study Amongst Portuguese Medical Students Versus Non- Medical Students. Acta Med. Port. 2018, 31, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n (%) | No. of Students with Depression | COR | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Family residency | 1.165 (0.597–2.271) | 0.654 | ||

| Bisha province | 118 (62.1) | 33 (28.0) | |||

| Another province | 72 (37.9) | 18 (25.0) | |||

| 2 | Nature of residency during the study | 2.096 (0.905–4.858) | 0.080 | ||

| With family or friends | 143 (75.3) | 43 (30.1) | |||

| Alone | 47 (24.7) | 08 (17.0) | |||

| 3 | Father education status | 0.773 (0.404–1.479) | 0.437 | ||

| University degree and above | 113 (59.5) | 28 (24.8) | |||

| Below University degree | 77 (40.5) | 23 (29.9) | |||

| 4 | Mother education status | 1.127 (0.593–2.142) | 0.716 | ||

| University degree and above | 89 (46.5) | 25 (28.1) | |||

| Below University degree | 101 (53.2) | 26 (25.7) | |||

| 5 | Satisfaction with family income | 2.747 (1.173–6.432) | 0.017 | ||

| Satisfied | 164 (86.3) | 39 (23.8) | |||

| Unsatisfied | 26 (13.7) | 12 (46.2) | |||

| 6 | Parental relationship | 0.441 (0.174–1.120) | 0.079 | ||

| Stable | 169 (88.9) | 42 (24.9) | |||

| Unstable | 21 (11.1) | 9 (42.9) | |||

| 7 | Loss of family members during last month | 2.91 (1.193–7.101) | 0.015 | ||

| Yes | 23 (12.1) | 11 (47.8) | |||

| No | 167 (87.9) | 40 (24.0) | |||

| 8 | Having, or having a family member with psychological illness | 2.581 (1.039–6.413) | 0.036 | ||

| Yes | 22 (11.6) | 10(45.5) | |||

| No | 168 (88.4) | 41(24.4) | |||

| 9 | Limited time for social activities | 1.088 (0.501–2.361) | 0.832 | ||

| Yes | 147 (77.4) | 40 (27.2) | |||

| No | 43 (22.6) | 11 (25.6) | |||

| 10 | Difficulties in personal relationships | 2.942 (1.447–5.981) | 0.002 | ||

| Yes | 45 (23.7) | 20 (44.4) | |||

| No | 145 (76.3) | 31 (21.4) | |||

| 11 | Use of stimulant | 1.897 (0.931–3.864) | 0.075 | ||

| Yes | 46 (24.2) | 17 (37.0) | |||

| No | 144 (75.8) | 34 (23.6) | |||

| 12 | Regret studying medicine | 5.245(2.583–10.650) | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 49 (25.8) | 26 (53.1) | |||

| No | 141 (74.2) | 25 (17.7) | |||

| 13 | Failed an academic year | 2.537 (1.293–4.975) | 0.006 | ||

| Yes | 57 (30.0) | 23 (40.4) | |||

| No | 133 (70.0) | 28 (21.1) | |||

| 14 | Lower grade than expected | 3.020 (1.316–6.928) | 0.007 | ||

| Yes | 132 (69.0) | 43 (32.6) | |||

| No | 58 (30.0) | 08 (13.8) | |||

| 15 | Conflict with teacher | 2.544 (1.098–5.892) | 0.026 | ||

| Yes | 27 (14.0) | 12 (44.4) | |||

| No | 163 (85.7) | 39 (23.9) | |||

| 16 | Deficiency of college facilities | 2.751 (1.008–7.508) | 0.041 | ||

| Yes | 153 (80.5) | 46 (30.1) | |||

| No | 37 (19.4) | 05 (13.5) | |||

| 17 | Heavy academic load | 2.310 (1.092–4.888) | 0.026 | ||

| Yes | 125 (65.7) | 40 (32.0) | |||

| No | 65 (34.2) | 11 (16.9) |

| Variable | AOR | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with family income | ||

| Satisfied | 2.393 (0.864–6.628) | 0.093 |

| Unsatisfied | Reference | |

| Loss of family members during last month | ||

| Yes | 3.69 (1.86–7.413) | 0.001 |

| No | Reference | |

| Having, or having a family member with psychological illness | ||

| Yes | 2.817 (0.927–8.559) | 0.068 |

| No | Reference | |

| Difficulties in personal relationships | ||

| Yes | 2.371 (1.009–5.575) | 0.048 |

| No | Reference | |

| Regretting studying medicine | ||

| Yes | 3.764 (1.657–8.550) | 0.002 |

| No | Reference | |

| Failing an academic year | ||

| Yes | 2.559 (1.112–5.887) | 0.027 |

| No | Reference | |

| Lower grade than expected | ||

| Yes | 2.556 (0.965–6.767) | 0.059 |

| No | Reference | |

| Conflict with teacher | ||

| Yes | 1.622 (0.581–4.524) | 0.355 |

| No | Reference | |

| Deficiency of college facilities | ||

| Yes | 1.664 (0.518–5.353) | 0.393 |

| No | Reference | |

| Heavy academic load | ||

| Yes | 1.206 (0.492–2.954) | 0.683 |

| No | Reference |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alshahrani, A.M.; Al-Shahrani, M.S.; Miskeen, E.; Alharthi, M.H.; Alamri, M.M.S.; Alqahtani, M.A.; Ibrahim, M.E. Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms and Its Correlates among Male Medical Students at the University of Bisha, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2024, 12, 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12060640

Alshahrani AM, Al-Shahrani MS, Miskeen E, Alharthi MH, Alamri MMS, Alqahtani MA, Ibrahim ME. Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms and Its Correlates among Male Medical Students at the University of Bisha, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare. 2024; 12(6):640. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12060640

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlshahrani, Abdullah M., Mohammad S. Al-Shahrani, Elhadi Miskeen, Muffarah Hamid Alharthi, Mohannad Mohammad S. Alamri, Mohammed A. Alqahtani, and Mutasim E. Ibrahim. 2024. "Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms and Its Correlates among Male Medical Students at the University of Bisha, Saudi Arabia" Healthcare 12, no. 6: 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12060640

APA StyleAlshahrani, A. M., Al-Shahrani, M. S., Miskeen, E., Alharthi, M. H., Alamri, M. M. S., Alqahtani, M. A., & Ibrahim, M. E. (2024). Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms and Its Correlates among Male Medical Students at the University of Bisha, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare, 12(6), 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12060640