Factors Associated with Hospitalized Community-Acquired Pneumonia among Elderly Patients Receiving Home-Based Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

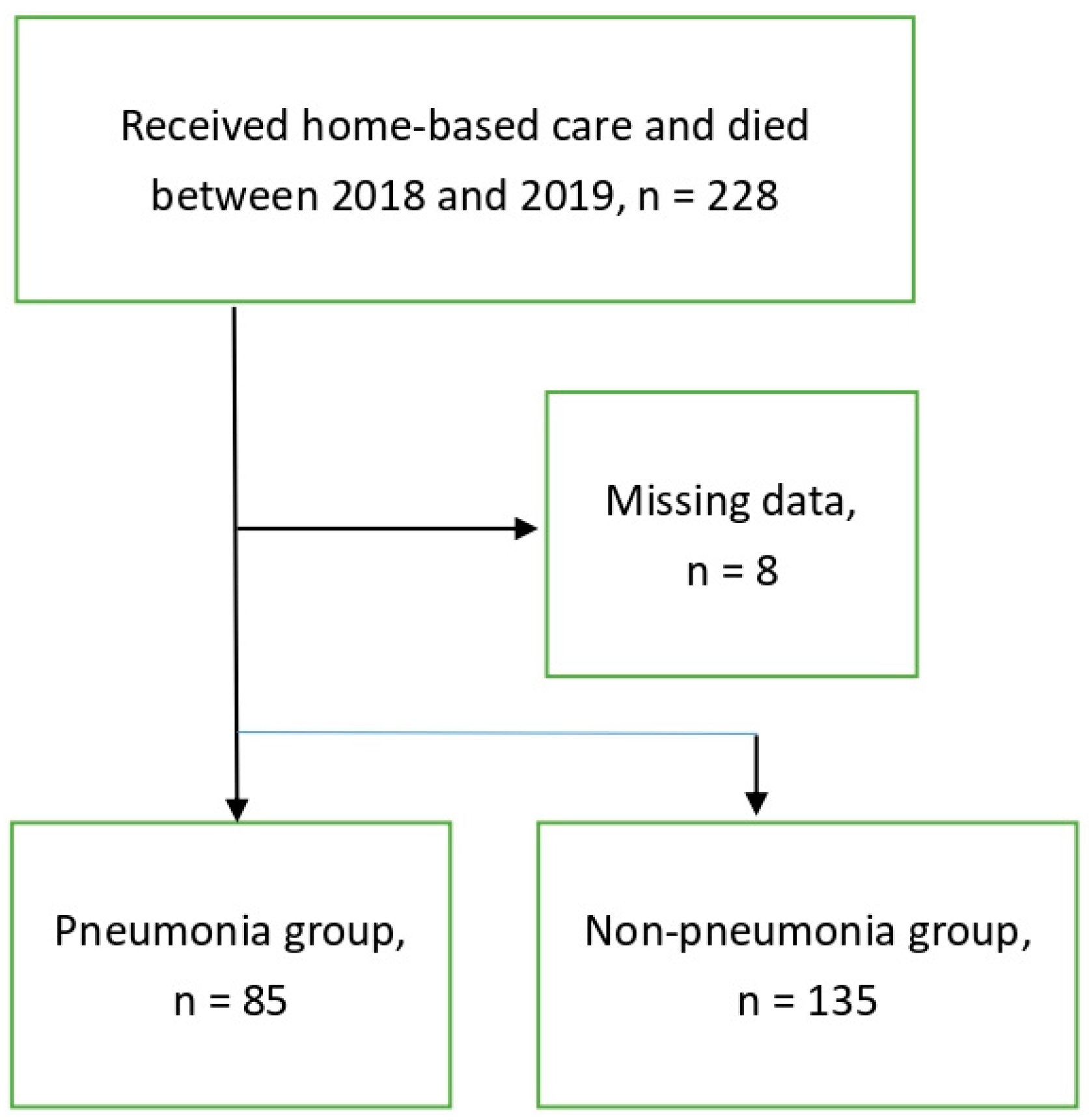

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Data Collection and Definition of Variables

2.2.2. Definition of Variables

2.3. Method

2.3.1. Data Design and Setting

2.3.2. Study Outcome

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bone, A.E.; Gomes, B.; Etkind, S.N.; Verne, J.; Murtagh, F.E.M.; Evans, C.J.; Higginson, I.J. What is the impact of population ageing on the future provision of end-of-life care? Population-based projections of place of death. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/ageing/en/ (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Available online: https://www.mohw.gov.tw/cp-5267-68139-1.html (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. The News Press of Ministry of Health and Welfare. Theme: Taiwan’s Leading Causes of Death in 2017. Available online: https://www.mohw.gov.tw/lp-4964-2.html (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Shen, Y.L.; Chuang, M.H.; Wu, M.P.; Woung, L.C.; Ho, C.Y.; Huang, S.J. Home Medical Care in Japan, Singapore and Taiwan: A Comparative Study Taiwan. J. Fam. Med. 2018, 28, 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.T.; Lai, H.Y.; Hwang, I.H.; Ho, M.M.; Hwang, S.J. Home healthcare services in Taiwan: A nationwide study among the older population. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, J.L. Analysis of Older Adults under Home Care in Taiwan’s Ageing Society. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 8687947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandell, L.A.; Wunderink, R.G.; Anzueto, A.; Bartlett, J.G.; Campbell, G.D.; Dean, N.C.; Dowell, S.F.; File, T.M., Jr.; Musher, D.M.; Niederman, M.S.; et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44 (Suppl. S2), S27–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokunaga, T.; Kubo, T.; Ryan, S.; Tomizawa, M.; Yoshida, S.; Takagi, K.; Furui, K.; Gotoh, T. Long-term outcome after placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2008, 8, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosaka, Y.; Nakagawa-Satoh, T.; Ohrui, T.; Fujii, M.; Arai, H.; Sasaki, H. Survival period after tube feeding in bedridden older patients. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2012, 12, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandell, L.A.; Niederman, M.S. Aspiration Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neill, S.; Dean, N. Aspiration pneumonia and pneumonitis: A spectrum of infectious/noninfectious diseases affecting the lung. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 32, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederman, M.S. Natural enemy or friend? Pneumonia in the very elderly critically ill patient. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2020, 29, 200031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, C.C.; Landrum, M.B.; Souza, J.M.; Neville, B.A.; Weeks, J.C.; Ayanian, J.Z. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: Is it a quality-of-care issue? J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3860–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.C.; Hu, C.C.; Loh, E.-W.; Hwang, S.F. Factors affecting the place of death among hospice home care cancer patients in Taiwan. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2014, 31, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, P.D.; Lerner, S.A. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet 1998, 352, 1295–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrie, T.J.; Lau, C.Y.; Wheeler, S.L.; Wong, C.J.; Vandervoort, M.K.; Feagan, B.G. A controlled trial of a critical pathway for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. CAPITAL Study Investigators. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Intervention Trial Assessing Levofloxacin. JAMA 2000, 283, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maret-Ouda, J.; Panula, J.; Santoni, G.; Xie, S.; Lagergren, J. Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of pneumonia: A self-controlled case series study. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 58, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warusevitane, A.; Karunatilake, D.; Sim, J.; Lally, F.; Roffe, C. Safety and effect of metoclopramide to prevent pneumonia in patients with stroke fed via nasogastric tubes trial. Stroke 2015, 46, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fohl, A.L.; Regal, R.E. Proton pump inhibitor-associated pneumonia: Not a breath of fresh air after all? World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 2, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takatori, K.; Yoshida, R.; Horai, A.; Satake, S.; Ose, T.; Kitajima, N.; Yoneda, S.; Adachi, K.; Amano, Y.; Kinoshita, Y. Therapeutic effects of mosapride citrate and lansoprazole for prevention of aspiration pneumonia in patients receiving gastrostomy feeding. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 48, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, L.; Paszat, L.; Chartier, C. Indicators of poor quality end-of-life cancer care in Ontario. J. Palliat. Care 2006, 22, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.F.; Wang, W.M.; Chen, Y.J. The Effectiveness of Home Services in Taiwan: A People-Centered Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Murphy, S.L.; Kochanek, K.D.; Bastian, B.A. Deaths: Final Data for 2013. Natl. Vital. Stat. Rep. 2016, 64, 1–119. [Google Scholar]

- Almirall, J.; Serra-Prat, M.; Bolibar, I.; Balasso, V. Risk Factors for Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Respiration 2017, 94, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.J.; Chang, Y.C.; Tsou, M.T.; Chan, H.L.; Chen, Y.J.; Hwang, L.C. Factors associated with hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia in home health care patients in Taiwan. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corica, B.; Tartaglia, F.; D’Amico, T.; Romiti, G.F.; Cangemi, R. Sex and gender differences in community-acquired pneumonia. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2022, 17, 1575–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero-Calle, I.; Pardo-Seco, J.; Aldaz, P.; Vargas, D.A.; Mascaros, E.; Redondo, E.; Diaz-Maroto, J.L.; Linares-Rufo, M.; Fierro-Alacio, M.J.; Gil, A.; et al. Incidence and risk factor prevalence of community-acquired pneumonia in adults in primary care in Spain (NEUMO-ES-RISK project). BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liapikou, A.; Cilloniz, C.; Torres, A. Drugs that increase the risk of community-acquired pneumonia: A narrative review. Expert. Opin. Drug Saf. 2018, 17, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, M.; Lewis, S.; Cranswick, G.; Forbes, J.; Collaboration, F.T. FOOD: A multicentre randomised trial evaluating feeding policies in patients admitted to hospital with a recent stroke. Health Technol. Assess. 2006, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Sanchez, E.; Ruano-Alvarez, M.A.; Diaz-Jimenez, J.; Diaz, A.J.; Ordonez, F.J. Enteral Nutrition by Nasogastric Tube in Adult Patients under Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.F.; Hsu, T.W.; Liang, C.S.; Yeh, T.C.; Chen, T.Y.; Chen, N.C.; Chu, C.S. The Efficacy and Safety of Tube Feeding in Advanced Dementia Patients: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis Study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.A., Jr.; Andriolo, R.B.; Bennett, C.; Lustosa, S.A.; Matos, D.; Waisberg, D.R.; Waisberg, J. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy versus nasogastric tube feeding for adults with swallowing disturbances. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD008096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizock, B.A. Risk of aspiration in patients on enteral nutrition: Frequency, relevance, relation to pneumonia, risk factors, and strategies for risk reduction. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2007, 9, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahnemai-Azar, A.A.; Rahnemaiazar, A.A.; Naghshizadian, R.; Kurtz, A.; Farkas, D.T. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: Indications, technique, complications and management. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 7739–7751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laheij, R.J.; Sturkenboom, M.C.; Hassing, R.J.; Dieleman, J.; Stricker, B.H.; Jansen, J.B. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia and use of gastric acid-suppressive drugs. JAMA 2004, 292, 1955–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theilacker, C.; Sprenger, R.; Leverkus, F.; Walker, J.; Hackl, D.; von Eiff, C.; Schiffner-Rohe, J. Population-based incidence and mortality of community-acquired pneumonia in Germany. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, J.K.; Kao, Y.H. Predictors of high healthcare costs in elderly patients with liver cancer in end-of-life: A longitudinal population-based study. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torner, N.; Izquierdo, C.; Soldevila, N.; Toledo, D.; Chamorro, J.; Espejo, E.; Fernandez-Sierra, A.; Dominguez, A.; Project, P.I.W.G. Factors associated with 30-day mortality in elderly inpatients with community acquired pneumonia during 2 influenza seasons. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2017, 13, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, A.A.; Keating, N.L.; Balboni, T.A.; Matulonis, U.A.; Block, S.D.; Prigerson, H.G. Place of death: Correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers’ mental health. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4457–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.T.; Wu, S.C.; Hung, Y.N.; Huang, E.W.; Chen, J.S.; Liu, T.W. Trends in quality of end-of-life care for Taiwanese cancer patients who died in 2000-2006. Ann. Oncol. 2009, 20, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Total | Non-P Group | P Group | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (220) | (135) | (85) | ||

| Gender | 0.004 a | |||

| Female | 111 (50.5%) | 79 (58.5%) | 32 (37.6%) | |

| Male | 109 (49.5%) | 56 (41.5%) | 53 (62.4%) | |

| Age | 82.0 ± 11.1 | 81.8 ± 11.4 | 82.3 ± 10.7 | 0.846 b |

| Primary diagnosis | ||||

| Cancer | 71 (32.2%) | 52 (38.5%) | 19 (22.4%) | 0.017 a |

| Lung | 11 (5.0%) | 11 (8.1%) | 0 (0) | 0.004 a |

| Colon–rectal | 19 (8.6%) | 12 (8.9%) | 7 (8.2%) | 1.000 a |

| Liver | 19 (8.6%) | 14 (10.4%) | 5 (5.9%) | 0.327 a |

| Others | 22 (10.0%) | 15 (11.1%) | 7 (8.2%) | 0.645 a |

| COPD | 13 (5.9%) | 7 (5.2%) | 6 (7.1%) | 0.570 a |

| Dementia | 52 (23.6%) | 37 (27.4%) | 15 (17.6%) | 0.106 a |

| Parkinsonism | 8 (3.6%) | 1 (0.7%) | 7 (8.2%.) | 0.006 a |

| Stroke | 54 (24.5%) | 28 (20.7%) | 26 (30.6%) | 0.109 a |

| ESRD | 12 (5.5%) | 5 (3.7%) | 7 (8.2%) | 0.221 a |

| CHF | 10 (4.5%) | 5 (3.7%) | 5 (5.9%) | 0.514 a |

| Clinical symptoms/signs | ||||

| Unconsciousness | 104 (47.3%) | 64 (47.4%) | 40 (47.1%) | 1 a |

| Fever | 49 (22.3%) | 29 (21.5%) | 20 (23.5%) | 0.594 a |

| Dyspnea | 40 (18.2%) | 23 (17.0%) | 17 (20.0%) | 0.594 a |

| Nausea/vomiting | 16 (7.3%) | 13 (9.7%) | 3 (3.5%) | 0.112 a |

| Respiratory rate, time/min | 19.0 ± 5.1 | 18.9 ± 6.2 | 18.9 ± 2.75 | 0.218 b |

| SBP, mmHg | 126.7 ± 20.5 | 126.6 ± 20.9 | 126.9 ± 19.8 | 0.932 c |

| DBP, mmHg | 71.6 ± 12.5 | 73.2 ± 12.5 | 69.0 ± 12.1 | 0.015 c |

| Heart rate, beat/min | 84.5 ± 17.9 | 84.8 ± 18.3 | 84.1 ± 17.4 | 0.814 c |

| NG tube | 146 (66.4%) | 74 (54.8%) | 72 (84.7%) | <0.001 a |

| Urinary catheter | 101 (45.9%) | 63 (46.7%) | 38 (44.7%) | 0.783 a |

| Medications | ||||

| PPIs | 32 (14.5%) | 23 (17.0%) | 9 (10.6%) | 0.239 a |

| H2 blocker | 67 (30.5%) | 40 (29.6%) | 27 (31.8%) | 0.765 a |

| Gastroprokinetic agents * | 53 (24.1%) | 37 (27.4%) | 16 (18.8%) | 0.195 a |

| Days of hospitalization ** | 8.4 ± 9.2 | 5.1 ± 7.6 | 13.6 ± 9.2 | <0.001 c |

| DNR | 165 (75.0%) | 95 (70.4%) | 70 (82.4%) | 0.968 a |

| ICU | 12 (5.5%) | 7 (5.2%) | 5 (5.9%) | 1 a |

| Hospice palliative care | 81 (36.8%) | 53 (39.3%) | 28 (32.9%) | 0.390 a |

| Death in the hospital | 147 (66.8%) | 75 (55.6%) | 72 (84.7%) | <0.001 a |

| Covariates | OR | Estimate | S.E. | Z Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male vs. female | 2.33 (1.34–4.08) | 0.85 | 0.28 | 2.99 | 0.003 |

| Age | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.777 |

| Primary diagnosis | |||||

| Cancer | |||||

| Colon–rectal | 0.92 (0.35–2.44) | −0.08 | 0.50 | −0.17 | 0.867 |

| Liver | 0.54 (0.19–1.56) | −0.62 | 0.54 | −1.14 | 0.255 |

| Others | 0.71 (0.28–1.84) | −0.33 | 0.48 | −0.69 | 0.490 |

| COPD | 1.39 (0.45–4.28) | 0.33 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.567 |

| Dementia | 0.57 (0.29–1.11) | −0.57 | 0.34 | −1.65 | 0.099 |

| Parkinsonism | 12.1 (1.45–99.6) | 2.49 | 1.08 | 2.31 | 0.021 |

| Stroke | 1.68 (0.90–3.13) | 0.52 | 0.32 | 1.64 | 0.100 |

| ESRD | 2.33 (0.72–7.60) | 0.85 | 0.60 | 1.41 | 0.160 |

| CHF | 1.63 (0.46–5.79) | 0.49 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.454 |

| Clinical symptoms/signs | |||||

| Unconsciousness | 0.99 (0.57–1.70) | −0.01 | 0.28 | −0.05 | 0.960 |

| Fever | 1.12 (0.59–2.15) | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.722 |

| Dyspnea | 1.22 (0.61–2.44) | 0.20 | 0.35 | 0.55 | 0.579 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 0.34 (0.09–1.23) | −1.08 | 0.66 | −1.64 | 0.101 |

| Respiratory rate, time/min | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | −0.00 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.963 |

| SBP, mmHg | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.932 |

| DBP, mmHg | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | −0.03 | 0.01 | −2.40 | 0.016 |

| Heart rate, beat/min | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.28 | 0.781 |

| NG tube | 4.57 (2.31–9.02) | 1.52 | 0.35 | 4.37 | <0.001 |

| Urinary catheter | 0.92 (0.54–1.59) | −0.08 | 0.28 | −0.28 | 0.776 |

| Medications | |||||

| PPIs | 0.58 (0.25–1.31) | −0.55 | 0.42 | −1.31 | 0.190 |

| H2 blocker | 1.11 (0.61–1.99) | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.738 |

| Gastroprokinetic agents * | 0.61 (0.32–1.91) | −0.49 | 0.34 | −1.44 | 0.149 |

| Days of hospitalization ** | 1.12 (1.09–1.16) | 0.11 | 0.02 | 6.15 | <0.001 |

| DNR | 1.96 (1.01–3.84) | 0.68 | 0.34 | 1.98 | 0.048 |

| ICU | 1.14 (0.35–3.72) | 0.13 | 0.60 | 0.22 | 0.825 |

| Hospice palliative care | 0.76 (0.43–1.34) | −0.27 | 0.29 | −0.95 | 0.345 |

| Death in the hospital | 4.43 (2.24–8.76) | 1.49 | 0.35 | 4.28 | <0.001 |

| OR (95% C.I.) | Estimate | S.E. | Z Value | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male vs. female | 4.10 (1.95–8.60) | 1.41 | 0.38 | 3.73 | <0.001 |

| NG tube | 8.85 (3.64–21.56) | 2.18 | 0.46 | 4.80 | <0.001 |

| PPIs | 0.37 (0.13–1.02) | −1.00 | 0.52 | −1.92 | 0.0546 |

| Admission days * | 1.13 (1.08–1.18) | 0.12 | 0.02 | 5.39 | <0.001 |

| Died in hospital | 3.59 (1.51–8.55) | 1.28 | 0.44 | 2.89 | 0.004 |

| intercept | 0.01 | −4.61 | 0.69 | −6.68 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chiang, J.-K.; Kao, H.-H.; Kao, Y.-H. Factors Associated with Hospitalized Community-Acquired Pneumonia among Elderly Patients Receiving Home-Based Care. Healthcare 2024, 12, 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12040443

Chiang J-K, Kao H-H, Kao Y-H. Factors Associated with Hospitalized Community-Acquired Pneumonia among Elderly Patients Receiving Home-Based Care. Healthcare. 2024; 12(4):443. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12040443

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiang, Jui-Kun, Hsueh-Hsin Kao, and Yee-Hsin Kao. 2024. "Factors Associated with Hospitalized Community-Acquired Pneumonia among Elderly Patients Receiving Home-Based Care" Healthcare 12, no. 4: 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12040443

APA StyleChiang, J.-K., Kao, H.-H., & Kao, Y.-H. (2024). Factors Associated with Hospitalized Community-Acquired Pneumonia among Elderly Patients Receiving Home-Based Care. Healthcare, 12(4), 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12040443