The Value of the COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale in the Assessment of Post-COVID among Residents of Long-Term Care Facilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Analysis and Interpretation

3. Results

3.1. Patients

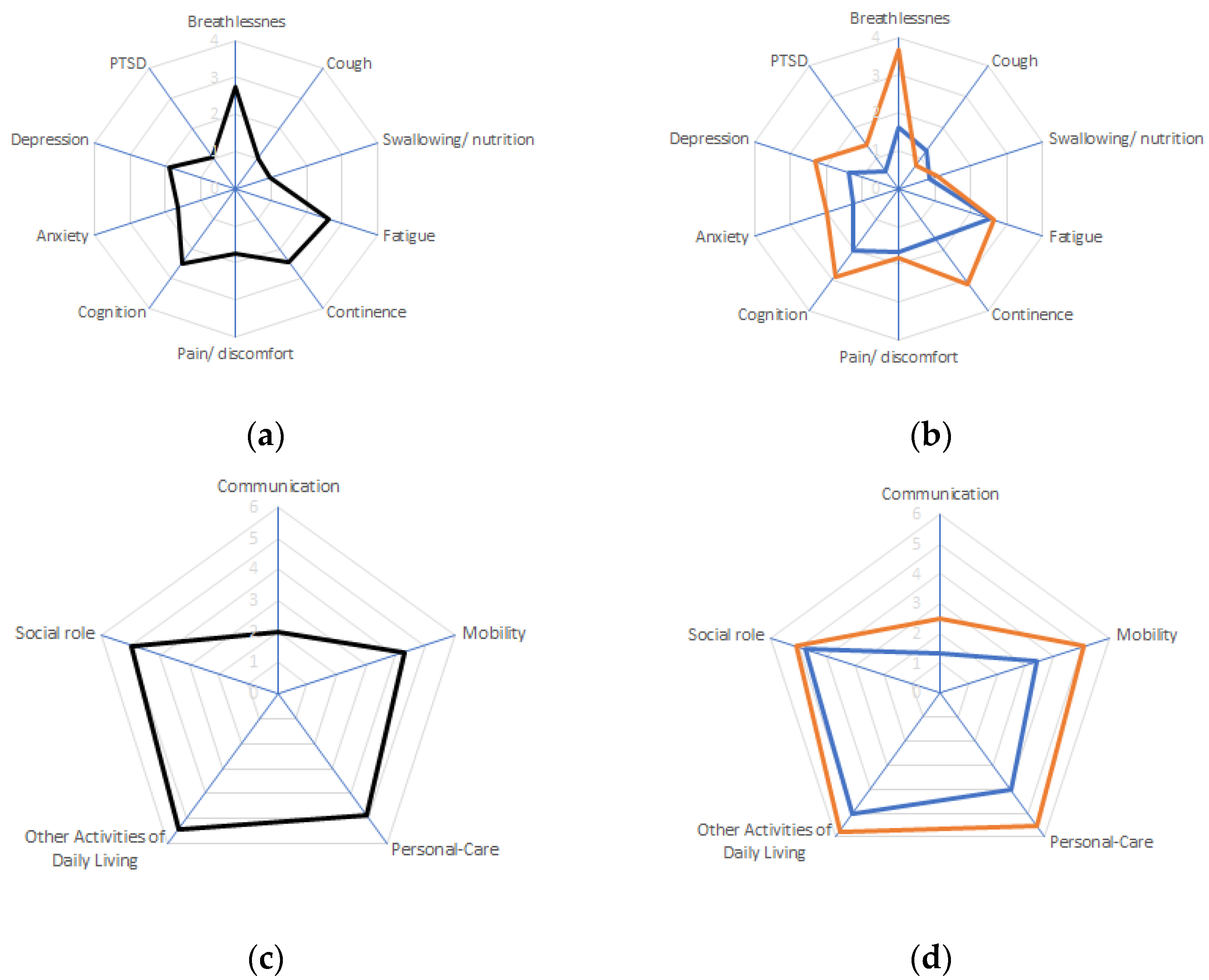

3.2. Post-COVID Burden Evaluated Using the COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale

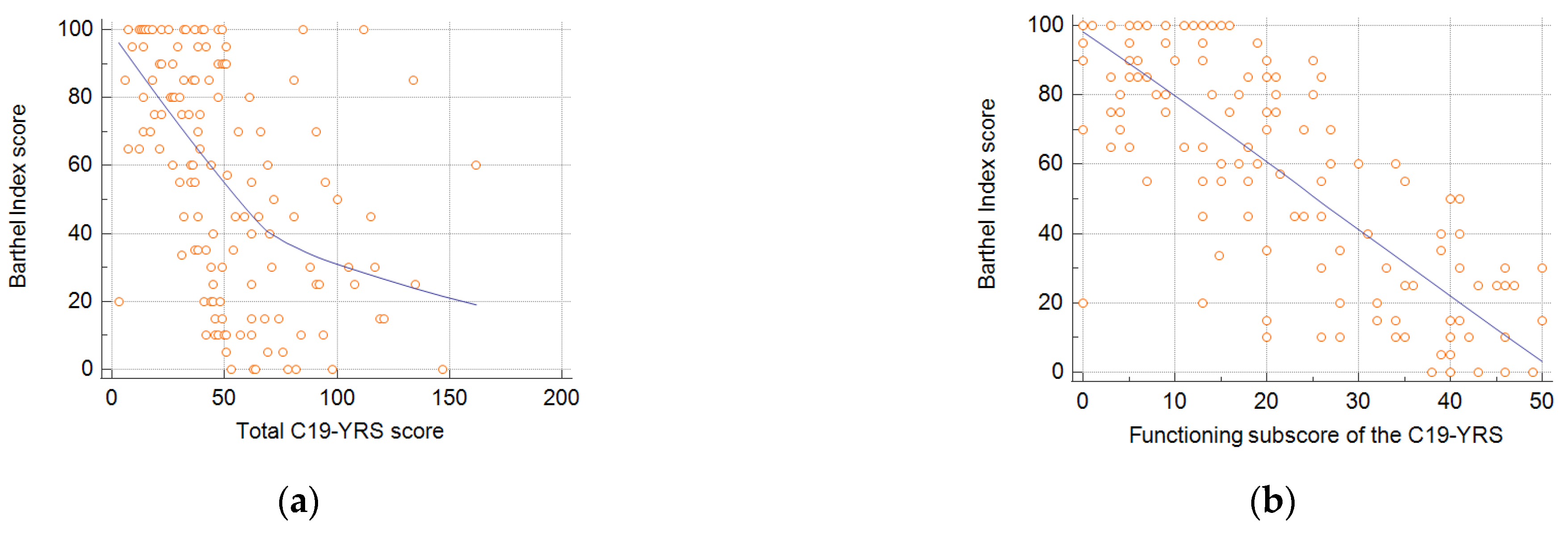

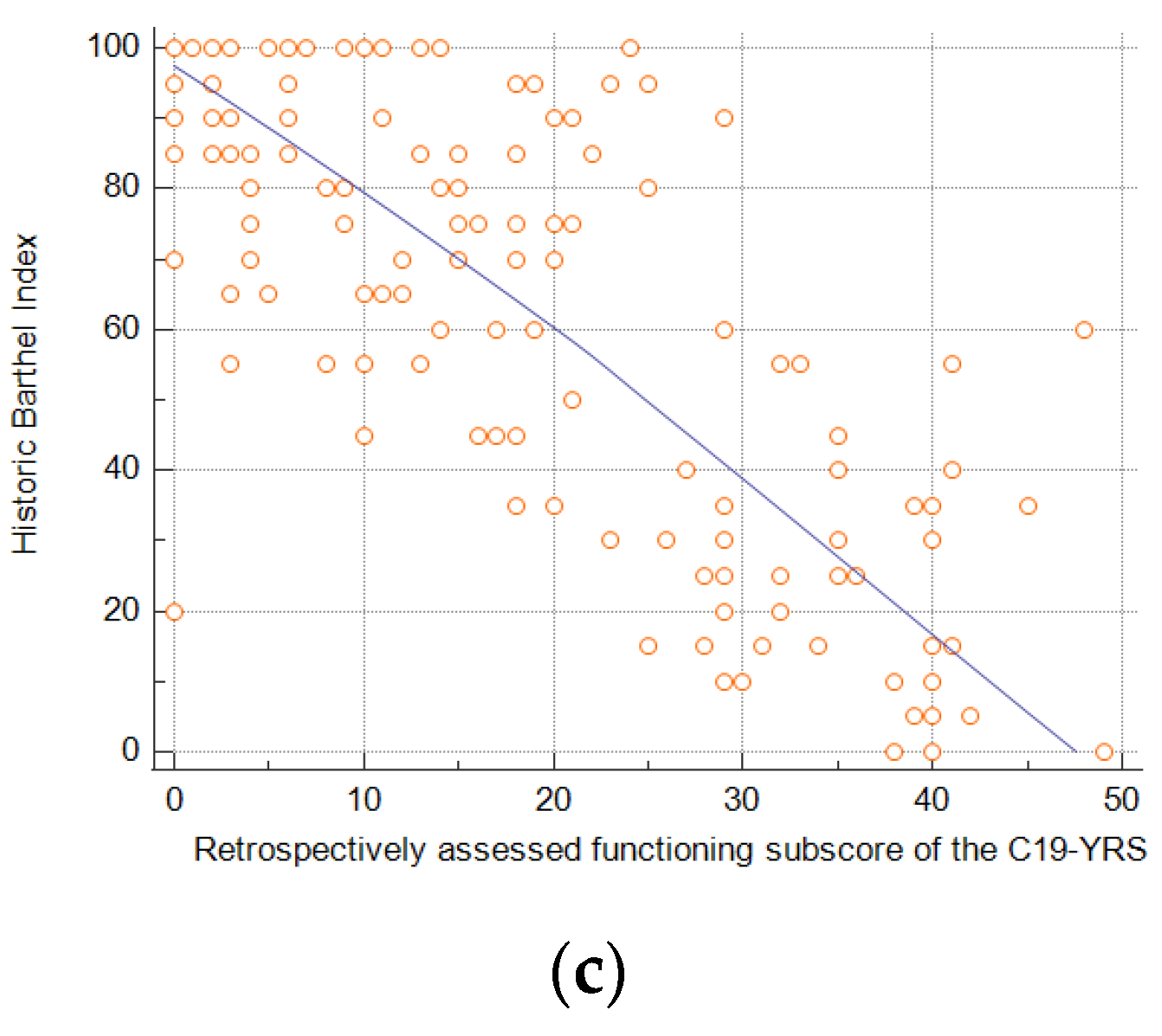

3.3. Correlation between Assessment Tools

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Therapeutics and COVID-19. Living guideline, 10 November 2023; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Burki, T. England and Wales see 20,000 excess deaths in care homes. Lancet 2020, 395, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, D.D.; Dick, A.; Agarwal, M.; Jones, K.M.; Mody, L.; Stone, P.W. COVID-19 Preparedness in Nursing Homes in the Midst of the Pandemic. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1164–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczerbińska, K. Could we have done better with COVID-19 in nursing homes? Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 11, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutikov, M.; Stirrup, O.; Nacer-Laidi, H.; Azmi, B.; Fuller, C.; Tut, G.; Palmer, T.; Shrotri, M.; Irwin-Singer, A.; Baynton, V.; et al. Outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 omicron infection in residents of long-term care facilities in England (VIVALDI): A prospective, cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022, 3, e347–e355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, W.W.; Keaton, A.A.; Ochoa, L.G.; Hatfield, K.M.; Gable, P.; Walblay, K.A.; Teran, R.A.; Shea, M.; Khan, U.; Stringer, G.; et al. Outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 Infections in Nursing Homes during Periods of Delta and Omicron Predominance, United States, July 2021–March 2022. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeve, L.; Tessier, E.; Trindall, A.; Aziz, N.; Andrews, N.; Futschik, M.; Rayner, J.; Didier’Serre, A.; Hams, R.; Groves, N.; et al. High attack rate in a large care home outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86, East of England, August 2023. Eurosurveillance 2023, 28, 2300489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danis, K.; Fonteneau, L.; Georges, S.; Daniau, C.; Bernard-Stoecklin, S.; Domegan, L.; O’Donnell, J.; Hauge, S.H.; Dequeker, S.; Vandael, E.; et al. High impact of COVID-19 in long-term care facilities, suggestion for monitoring in the EU/EEA, May 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2000956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, J.B.; Murthy, S.; Marshall, J.C.; Relan, P.; Diaz, J.V. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e102–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re’em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 Months of symptoms and their impact. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaweethai, T.; Jolley, S.E.; Karlson, E.W.; Levitan, E.B.; Levy, B.; McComsey, G.A.; McCorkell, L.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Parthasarathy, S.; Singh, U.; et al. Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA 2023, 329, 1934–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevissón-Redondo, B.; López-López, D.; Pérez-Boal, E.; Marqués-Sánchez, P.; Liébana-Presa, C.; Navarro-Flores, E.; Jiménez-Fernández, R.; Corral-Liria, I.; Losa-Iglesias, M.; Becerro-de-Bengoa-Vallejo, R. Use of the Barthel Index to Assess Activities of Daily Living before and after SARS-COVID 19 Infection of Institutionalized Nursing Home Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goździewicz, Ł.; Tobis, S.; Chojnicki, M.; Chudek, J.; Wieczorowska-Tobis, K.; Idasiak-Piechocka, I.; Merks, P.; Religioni, U.; Neumann-Podczaska, A. Long-Term Impairment in Activities of Daily Living Following COVID-19 in Residents of Long-Term Care Facilities. Med. Sci. Monit. 2023, 29, e941197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso García, B.; Romay Lema, E.; Rabuñal Rey, R. Useful tools in post-COVID syndrome evaluation. Med. Clin. 2022, 159, e33–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levere, M.; Rowan, P.; Wysocki, A. The Adverse Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Nursing Home Resident Well-Being. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 948–954.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnahan, J.L.; Lieb, K.M.; Albert, L.; Wagle, K.; Kaehr, E.; Unroe, K.T. COVID-19 disease trajectories among nursing home residents. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 2412–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, G.I.; Noale, M.; Trevisan, C.; Zatti, G.; Dalla Pozza, M.; Lazzarin, M.; Haxhiaj, L.; Ramon, R.; Imoscopi, A.; Bellon, S.; et al. Increase in Frailty in Nursing Home Survivors of Coronavirus Disease 2019: Comparison With Noninfected Residents. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 943–947.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, J.M.; Crooks, V.A.; Freeman, S.; Carroll, S.; Davison, K.M.; MacPhee, M.; Berndt, A.; Walls, J.; Mithani, A. A call to action to enhance understanding of long COVID in long-term care home residents. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 1943–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, S.E.; Bautista, L.; Neeb, K.; Montoya, A.; Gibson, K.E.; Mantey, J.; Kabeto, M.; Min, L.; Mody, L. Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC) in nursing home residents: A retrospective cohort study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, R.J.; Preston, N.; Parkin, A.; Makower, S.; Ross, D.; Gee, J.; Halpin, S.J.; Horton, M.; Sivan, M. The COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRS): Application and psychometric analysis in a post-COVID-19 syndrome cohort. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivan, M.; Halpin, S.; Gee, J.; Makower, S.; Parkin, A.; Ross, D.; Horton, M.; O’Connor, R. The self-report version and digital format of the COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19YRS) for Long COVID or Post-COVID syndrome assessment and monitoring. ACNR 2021, 20, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, M.; Preston, N.; Parkin, A.; Makower, S.; Gee, J.; Ross, D.; Tarrant, R.; Davison, J.; Halpin, S.; O’Connor, R.J.; et al. The modified COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C19-YRSm) patient-reported outcome measure for Long Covid or Post-COVID-19 syndrome. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 4253–4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mińko, A.; Turoń-Skrzypińska, A.; Rył, A.; Tomska, N.; Bereda, Z.; Rotter, I. Searching for Factors Influencing the Severity of the Symptoms of Long COVID. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Chung, V.C.; Chan, D.C.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, W.; Tam, K.W.; Lee, R.C.; Sit, R.W.; Mercer, S.W.; Wong, S.Y. Determinants of post-COVID-19 symptoms among adults aged 55 or above with chronic conditions in primary care: Data from a prospective cohort in Hong Kong. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1138147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, F.F.; Xu, S.; Kwong, T.M.H.; Li, A.S.; Ha, E.H.; Hua, H.; Liong, C.; Leung, K.C.; Leung, T.H.; Lin, Z.; et al. Prevalence, Patterns, and Clinical Severity of Long COVID among Chinese Medicine Telemedicine Service Users: Preliminary Results from a Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso García, B.; Besteiro Balado, Y.; Pérez López, A.; Romay Lema, E.; Marchán-López, Á.; Rodríguez Álvarez, A.; García País, M.J.; Corredoira Sánchez, J.; Rabuñal Rey, R. Assessment of Post-COVID Symptoms Using the C19-YRS Tool in a Cohort of Patients from the First Pandemic Wave in Northwestern Spain. Telemed. J. E Health 2023, 29, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Shen, Q.; Guo, W.; He, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Deng, D.; Ouyang, X.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Elderly Patients with COVID-19 in Hunan Province, China: A Multicenter, Retrospective Study. Gerontology 2020, 66, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull-Otterson, L.; Baca, S.; Saydah, S.; Boehmer, T.; Adjei, S.; Gray, S.; Harris, A. Post–COVID Conditions Among Adult COVID-19 Survivors Aged 18–64 and ≥65 Years—United States, March 2020–November 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, M.; Parkin, A.; Makower, S.; Greenwood, D.C. Post-COVID syndrome symptoms, functional disability, and clinical severity phenotypes in hospitalized and nonhospitalized individuals: A cross-sectional evaluation from a community COVID rehabilitation service. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.H. Biostatistics 104: Correlational analysis. Singap. Med. J. 2003, 44, 614–619. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, K.; Ren, S.; Heath, K.; Dasmariñas, M.C.; Jubilo, K.G.; Guo, Y.; Lipsitch, M.; Daugherty, S.E. Risk of persistent and new clinical sequelae among adults aged 65 years and older during the post-acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2022, 376, e068414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, E.Y.F.; Zhang, R.; Mathur, S.; Yan, V.K.C.; Lai, F.T.T.; Chui, C.S.L.; Li, X.; Wong, C.K.H.; Chan, E.W.Y.; Lau, C.S.; et al. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 in older persons: Multi-organ complications and mortality. J. Travel. Med. 2023, 30, taad082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daitch, V.; Yelin, D.; Awwad, M.; Guaraldi, G.; Milić, J.; Mussini, C.; Falcone, M.; Tiseo, G.; Carrozzi, L.; Pistelli, F.; et al. Characteristics of long-COVID among older adults: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 125, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamadoni, N.; Bakhtiari, A.; Nikbakht, H.A. Psychometric properties of the COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale: Post-COVID-19 syndrome in Iranian elderly population. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbeis, F.; Thibeault, C.; Doellinger, F.; Ring, R.M.; Mittermaier, M.; Ruwwe-Glösenkamp, C.; Alius, F.; Knape, P.; Meyer, H.J.; Lippert, L.J.; et al. Severity of respiratory failure and computed chest tomography in acute COVID-19 correlates with pulmonary function and respiratory symptoms after infection with SARS-CoV-2: An observational longitudinal study over 12 months. Respir. Med. 2022, 191, 106709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poloni, T.E.; Medici, V.; Zito, A.; Carlos, A.F. The long-COVID-19 in older adults: Facts and conjectures. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 2679–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y. Respiratory rehabilitation in elderly patients with COVID-19: A randomized controlled study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 39, 101166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emordi, V.; Lo, A.; Bisharat, M.; Malakounides, G. COVID-19-Induced Bladder and Bowel Incontinence: A Hidden Morbidity? Clin. Pediatr. 2024, 63, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.; Faisal, S.; Rashid, H.H.; Sharif, K.; Habib, H.; Khalid, M.; Hassan, Z. Frequency of Urinary Incontinence Among Post COVID Males. J. Health Rehabil. Res. 2023, 3, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotan, A.; Muller, S.; Kanduc, D.; David, P.; Halpert, G.; Shoenfeld, Y. The SARS-CoV-2 as an instrumental trigger of autoimmunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 2021, 20, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, J.S.; Mazenett-Granados, E.A.; Salazar-Uribe, J.C.; Sarmiento, M.; Suárez, J.F.; Rojas, M.; Munera, M.; Pérez, R.; Morales, C.; Dominguez, J.I.; et al. Increased incidence of rheumatoid arthritis after COVID-19. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 22, 103409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Yen-Ting Chen, T.; Wang, S.I.; Hung, Y.M.; Chen, H.Y.; Wei, C.J. Risk of autoimmune diseases in patients with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 56, 101783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro-Pennarolli, C.; Sánchez-Rojas, C.; Torres-Castro, R.; Vera-Uribe, R.; Sanchez-Ramirez, D.C.; Vasconcello-Castillo, L.; Solís-Navarro, L.; Rivera-Lillo, G. Assessment of activities of daily living in patients post COVID-19: A systematic review. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, D.T.; Collin, C. The Barthel ADL Index: A standard measure of physical disability? Int. Disabil. Stud. 1988, 10, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivan, M.; Rocha Lawrence, R.; O’Brien, P. Digital Patient Reported Outcome Measures Platform for Post-COVID-19 Condition and Other Long-Term Conditions: User-Centered Development and Technical Description. JMIR Hum. Factors 2023, 10, e48632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Patients (n = 144) |

|---|---|

| Mean age, years (±SD) | 78.7 (±9.4) |

| Males, n (%) | 57 (39.6%) |

| Clinical course of COVID-19, n (%) | |

| Not hospitalized | 66 (45.8%) |

| Requiring hospitalization | 78 (54.2%) |

| Mean C19-YRS score (±SD) | 51.2 (±31.2) |

| Mean Barthel index score (±SD) | 57.1 (±33.5) |

| C19-YRS Subscales/Items, Mean ± SD | All Patients | Non-Hospitalized Patients | Hospitalized Patients | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom subscale | 18.6 ± 17.4 | 14.9 ± 15.9 | 21.7 ± 18.2 | 0.0180 |

| Breathlessness | 2.7 ± 3.2 | 1.6 ± 2.4 | 3.7 ± 3.5 | <0.001 |

| Cough | 1.0 ± 2.2 | 1.2 ± 2.4 | 0.8 ± 2.0 | 0.2170 |

| Swallowing/nutrition | 1.0 ± 2.5 | 0.8 ± 2.3 | 1.1 ± 2.7 | 0.6270 |

| Fatigue | 2.6 ± 3.1 | 2.6 ± 3.1 | 2.7 ± 3.1 | 0.8630 |

| Continence | 2.4 ± 3.7 | 1.6 ± 3.2 | 3.1 ± 4.0 | 0.0150 |

| Pain/discomfort | 1.8 ± 2.9 | 1.7 ± 2.7 | 1.8 ± 3.0 | 0.7530 |

| Cognition | 2.5 ± 3.4 | 2.0 ± 3.0 | 2.9 ± 3.7 | 0.1470 |

| Anxiety | 1.7 ± 2.9 | 1.3 ± 2.6 | 2.0 ± 3.0 | 0.1310 |

| Depression | 1.9 ± 2.7 | 1.4 ± 2.5 | 2.3 ± 2.8 | 0.0410 |

| PTSD 1 | 1.1 ± 2.4 | 0.6 ± 1.7 | 1.4 ± 2.8 | 0.0320 |

| Functioning subscale | 21.5 ± 14.8 | 18.6 ± 14.4 | 24.0 ± 17.2 | 0.0280 |

| Communication | 2.0 ± 3.1 | 1.3 ± 2.6 | 2.5 ± 3.4 | 0.0200 |

| Mobility | 4.3 ± 3.7 | 3.4 ± 3.5 | 5.1 ± 3.7 | 0.0070 |

| Personal care | 4.8 ± 3.7 | 4.0 ± 3.7 | 5.5 ± 3.6 | 0.0150 |

| Other ADL | 5.4 ± 3.8 | 5.1 ± 4.0 | 5.8 ± 3.6 | 0.2620 |

| Social role | 4.9 ± 4.2 | 4.8 ± 4.3 | 5.1 ± 4.3 | 0.6290 |

| Health overall | 5.3 ± 2.5 | 5.3 ± 2.3 | 5.3 ± 2.7 | 0.9630 |

| Additional symptom subscale | 5.9 ± 7.6 | 5.8 ± 7.6 | 5.9 ± 7.8 | 0.9440 |

| Palpitations | 0.7 ± 1.8 | 0.8 ± 1.8 | 0.7 ± 1.8 | 0.7970 |

| Dizziness/falls | 1.3 ± 2.1 | 1.1 ± 1.9 | 1.4 ± 2.3 | 0.3840 |

| Weakness | 2.0 ± 2.4 | 1.8 ± 2.0 | 2.3 ± 2.7 | 0.2310 |

| Sleep problems | 1.4 ± 2.4 | 1.5 ± 2.6 | 1.3 ± 2.3 | 0.6430 |

| Fever | 0.2 ± 0.7 | 0.2 ± 0.7 | 0.1 ± 0.7 | 0.6400 |

| Skin rash | 0.3 ± 1.3 | 0.6 ± 1.8 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.0100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goździewicz, Ł.; Tobis, S.; Chojnicki, M.; Wieczorowska-Tobis, K.; Neumann-Podczaska, A. The Value of the COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale in the Assessment of Post-COVID among Residents of Long-Term Care Facilities. Healthcare 2024, 12, 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12030333

Goździewicz Ł, Tobis S, Chojnicki M, Wieczorowska-Tobis K, Neumann-Podczaska A. The Value of the COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale in the Assessment of Post-COVID among Residents of Long-Term Care Facilities. Healthcare. 2024; 12(3):333. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12030333

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoździewicz, Łukasz, Sławomir Tobis, Michał Chojnicki, Katarzyna Wieczorowska-Tobis, and Agnieszka Neumann-Podczaska. 2024. "The Value of the COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale in the Assessment of Post-COVID among Residents of Long-Term Care Facilities" Healthcare 12, no. 3: 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12030333

APA StyleGoździewicz, Ł., Tobis, S., Chojnicki, M., Wieczorowska-Tobis, K., & Neumann-Podczaska, A. (2024). The Value of the COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale in the Assessment of Post-COVID among Residents of Long-Term Care Facilities. Healthcare, 12(3), 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12030333