Safety of Thread-Embedding Acupuncture: A Multicenter, Prospective, Observational Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Outcome Measures

2.3. Procedures and Enrollment

2.4. Data Sources and Measurement

2.5. Sample Size

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Adverse Events Related to TEA

3.3. Bivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Woo, S.H.; Lee, H.J.; Park, Y.K.; Han, J.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, J.H.; Park, C.A.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, W.D.; Yang, C.S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of thread embedding acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Medicine 2022, 101, e29306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.M.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, E.Y.; Roh, J.D.; Jo, N.Y.; Lee, C.K. A systematic review on thread embedding therapy of knee osteoarthritis. J. Acupunct. Res. 2018, 35, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, H.L.; Lu, S.S.; Fan, P.X.; Yi, W.; Ji, X.L. Acupoint catgut embedding for treatment of chronic pelvic pain due to the sequelae of pelvic inflammatory disease. J. Vis. Exp. 2024, e66438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, M.; Feng, H.; Jin, C.; Xu, L.; Lin, T. Intractable facial paralysis treated with different acupuncture and acupoint embedding therapies: A randomized controlled trial. Chin. Acupunct. Moxibustion 2015, 35, 997–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. Acupuncture combined with catgut embedding therapy for treatment of 158 cases of facial paralysis. Chin. Acupunct. Moxibustion 2005, 25, 167–168. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, J.; Jin, X.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X. The effectiveness of acupoint catgut embedding therapy for abdominal obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2019, 2019, 9714313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, Y.; Choi, I. Effect of thread embedding acupuncture for facial wrinkles and laxity: A single-arm, prospective, open-label study. Integr. Med. Res. 2017, 6, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KAMSTC. The Acupuncture and Moxibustion Medicine, 1st ed.; HANMI Medical Publishing Co.: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava, D.; Anantanarayanan, P.; Prakash, G.; Dare, B.J.; Deshpande, A. Initial inflammatory response of skeletal muscle to commonly used suture materials: An animal model study to evaluate muscle healing after surgical repair–histopathological perspective. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2013, 18, e491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, M.; Xu, J.; Yang, Y. Progress in absorbable polymeric thread used as acupoint embedding material. Polym. Test. 2021, 101, 107298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.W.; Shin, B.H.; Heo, C.Y.; Shim, J.H. Efficacy study of the new polycaprolactone thread compared with other commercialized threads in a murine model. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 2743–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.; Kim, S.S.; Oh, S.M.; Kim, B.C.; Jung, W. Tissue changes over time after polydioxanone thread insertion: An animal study with pigs. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2019, 18, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, Y.I.; Kim, J.H.; Park, E.S. Histological and molecular biological analysis on the reaction of absorbable thread; Polydioxanone and polycaprolactone in rat model. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 2774–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, J.A.; Lach, A.A.; Morris, H.L.; Carr, A.J.; Mouthuy, P.-A. Polydioxanone implants: A systematic review on safety and performance in patients. J. Biomater. Appl. 2020, 34, 902–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwangbo, H.; Moon, S.H.; Jung, S.W.; Lee, S.K. Mycobacterium abscessus skin infection following the embedding therapy in an oriental clinic. Korean J. Dermatol. 2016, 54, 155–156. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, J.H.; Chun, J.H.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, H.O.; Park, Y.M. Two cases of facial foreign body granuloma induced by needle-embedding therapy. Korean J. Dermatol. 2011, 49, 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- Yook, H.; Kim, Y.H.; Han, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Park, Y.M.; Bang, C.H. A case of foreign body granuloma developing after gold thread acupuncture. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2022, 88, 222–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, S.H.; Lee, Y.B.; Han, D.G. Early Complications from Absorbable Anchoring Suture Following Thread-Lift for Facial Rejuvenation. Arch. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2017, 23, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avishai, E.; Yeghiazaryan, K.; Golubnitschaja, O. Impaired wound healing: Facts and hypotheses for multi-professional considerations in predictive, preventive and personalised medicine. EPMA J. 2017, 8, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.J.; Liang, J.Q.; Xu, X.K.; Xu, Y.X.; Chen, G.Z. Safety of thread embedding acupuncture therapy: A systematic review. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2021, 27, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi, A.H.; Adel-Mehraban, M.S.; Dastjerdi, M.J.; Alipour, R. A comprehensive practical review of acupoint embedding as a semi-permanent acupuncture: A mini review. Medicine 2024, 103, e38314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Use of the WHO-UMC System for Standardized Case Causality Assessment; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arain, M.; Campbell, M.J.; Cooper, C.L.; Lancaster, G.A. What is a pilot or feasibility study? A review of current practice and editorial policy. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.; Goo, B.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Nam, S.S. Clinical use of thread embedding acupuncture for facial nerve palsy: A web-based survey. Medicine 2022, 101, e31507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Yao, W.; Li, Y.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Troulis, M.J.; August, M.; Chen, Y.; Han, Y. A meta-analysis and systematic review of the incidences of complications following facial thread-lifting. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2021, 45, 2148–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trone, J.; Ollier, E.; Chapelle, C.; Bertoletti, L.; Cucherat, M.; Mismetti, P.; Magne, N.; Laporte, S. Statistical controversies in clinical research: Limitations of open-label studies assessing antiangiogenic therapies with regard to evaluation of vascular adverse drug events—A meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Adverse Events | No Adverse Events | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 100 | 10 | 90 |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 32 (32.0%)/68 (68.0%) | 2 (20.0%)/8 (80.0%) | 31 (33.3%)/61 (66.7%) |

| Age (year) | 49.1 14.5 | 47.5 11.8 | 49.3 14.8 |

| Height (cm) | 163.1 8.3 | 159.9 11.0 | 163.5 7.9 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.5 14.1 | 59.4 10.2 | 65.0 14.4 |

| Participants with comorbidities | 38 (38.0%) | 3 (30.0%) | 35 (38.9%) |

| Type of comorbidities | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 12 (12.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | 11 (12.2%) |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 16 (16.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 14 (15.6%) |

| Urogenital disorders | 4 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (4.4%) |

| Endocrine disorders | 14 (14.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 14 (15.6%) |

| Digestive disorders | 2 (2.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.2%) |

| Other conditions | 6 (6.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | 5 (5.6%) |

| Total | 54 (54.0%) | 4 (40.0%) | 50 (55.3%) |

| Vital sign | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm/Hg) | 124.5 15.1 | 125.8 14.1 | 124.3 15.2 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm/Hg) | 74.7 9.5 | 75.7 13.4 | 74.6 9.1 |

| Pulse rate (bpm) | 74.6 10.4 | 78.6 17.5 | 74.2 9.3 |

| Temperature (°C) | 36.5 0.2 | 36.4 0.1 | 36.5 0.2 |

| Conditions treated with TEA | |||

| Cosmetic purposes | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (1.1%) |

| Low back pain | 27 (27.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | 26 (28.9%) |

| Neck pain | 15 (15.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 15 (16.7%) |

| Shoulder pain | 8 (8.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (8.9%) |

| Elbow pain | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.1%) |

| Ankle pain | 3 (3.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | 2 (2.2%) |

| Facial paralysis | 56 (56.0%) | 7 (70.0%) | 49 (54.4%) |

| Other conditions | 2 (2.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | 1 (1.1%) |

| Previous TEA experiences | |||

| Yes | 72 (72.0%) | 7 (70.0%) | 65 (72.2%) |

| No | 28 (28.0%) | 3 (30.0%) | 25 (27.8%) |

| History of TEA-related adverse events | |||

| Yes | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.1%) |

| No | 99 (99.0%) | 10 (100.0%) | 89 (98.9%) |

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 100 |

| Patients with one or more adverse event | 10 (10.0%) |

| Number of TEA session | |

| 1 session | 3 (30.0%) |

| More than 1 session | 7 (70.0%) |

| Total Visit | 136 |

| Number of adverse events | 12 (8.8%) |

| Treatment-related adverse events * | |

| Pain | 5 (45.5%) |

| Bruise | 5 (45.5%) |

| Foreign body sensation and tension | 1 (9.1%) |

| Severity of adverse events | |

| Mild | 12 (100.0%) |

| Moderate | 0 (0.0%) |

| Severe | 0 (0.0%) |

| Management of adverse events | |

| TEA maintained | 12 (100.0%) |

| TEA stopped | 0 (0.0%) |

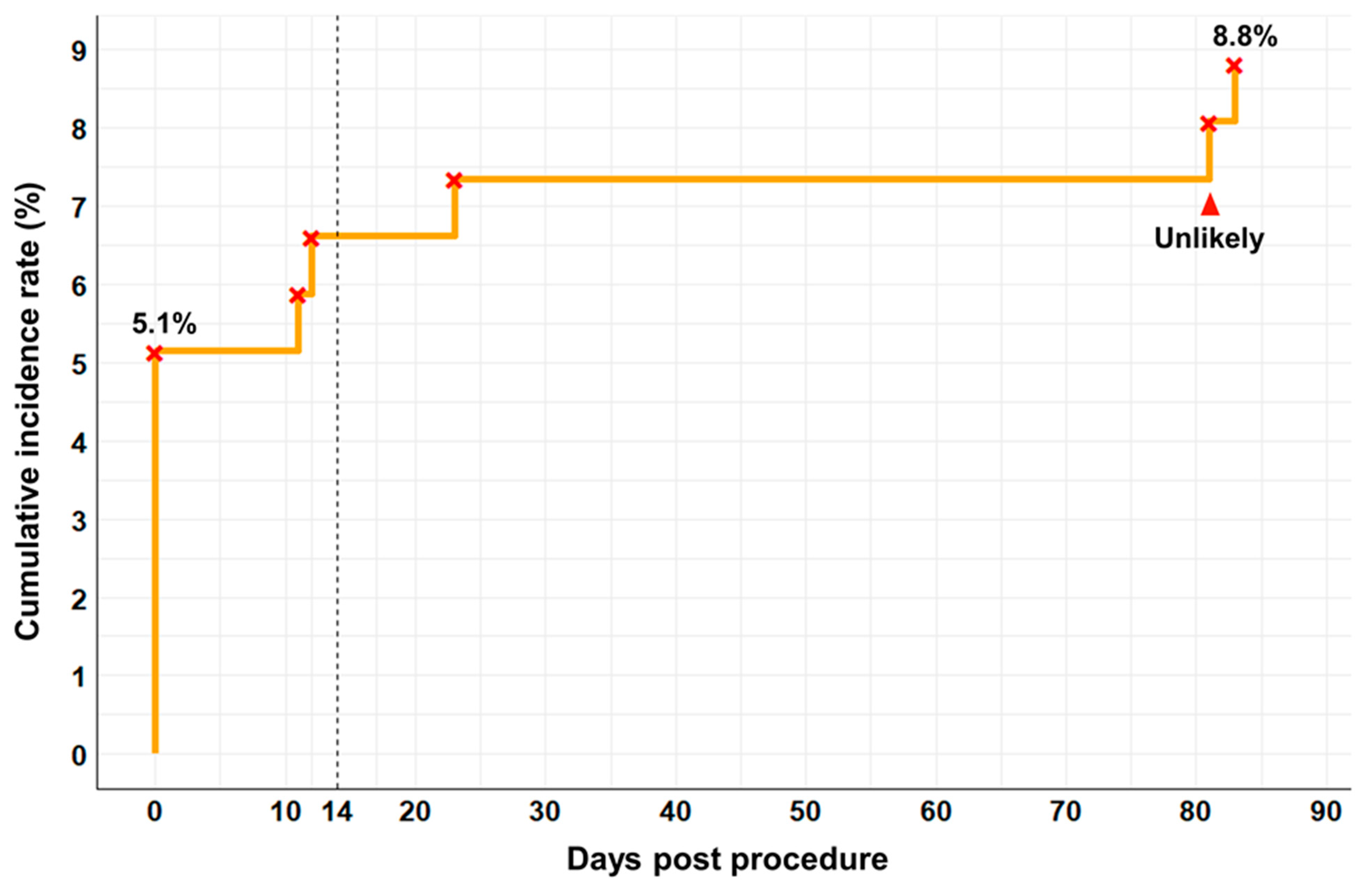

| Timing of adverse events after first-procedure | |

| Within 14 days | 7 (58.3%) |

| 14 days–1 month | 3 (25.0%) |

| 1 month–3 months | 2 (16.7%) |

| Over 3 months | 0 (0.0%) |

| Timing of adverse events after last procedure | |

| Within 14 days | 8 (66.7%) |

| 14 days–1 month | 2 (16.7%) |

| 1 month–3 months | 2 (16.7%) |

| Over 3 months | 0 (0.0%) |

| Duration of adverse events † | |

| Pain | 7.3 4.5 |

| Bruise | 8.8 3.4 |

| Total | 8.8 4.3 |

| Outcome of adverse events | |

| Recovery without sequelae | 12 (100.0%) |

| Total (N = 136) | Adverse Events (N = 11) | No Adverse Events (N = 125) | p-Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Male/Female) | 40/96 | 2/9 | 38/87 | 0.5072 | 0.51 (0.10, 2.47) |

| Comorbidities (Yes/No) | 53/83 | 4/7 | 49/76 | 0.9999 | 0.89 (0.25, 3.19) |

| Previous TEA experiences (Yes/No) | 93/43 | 8/3 | 85/40 | 0.9999 | 1.25 (0.32, 4.98) |

| Number of TEA session | |||||

| 1 session/More than 1 sessions | 100/36 | 4/7 | 96/29 | 0.0078 * | 0.17 (0.05, 0.63) † |

| TEA treatment site | |||||

| Facial | 89 (65.4%) | 8 (72.7%) | 81 (64.8%) | 0.7476 | 1.45 (0.37, 5.74) |

| Neck | 16 (11.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (12.8%) | 0.3609 | - |

| Shoulder | 11 (8.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (8.8%) | 0.5993 | - |

| Lumbar | 29 (21.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | 28 (22.4%) | 0.4564 | 0.35 (0.04, 2.82) |

| Buttocks | 5 (3.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (4.0%) | 0.9999 | - |

| Upper limb | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0.9999 | - |

| Lower limb | 10 (7.4%) | 2 (18.2%) | 8 (6.4%) | 0.1870 | 3.25 (0.60, 17.64) |

| Suture size | |||||

| 6–0 | 128 (95.5%) | 11 (100.0%) | 117 (95.1%) | 0.9999 | - |

| 5–0 | 9 (6.7%) | 0 (0.00%) | 9 (7.3%) | 0.9999 | - |

| Needle length | |||||

| 25 mm | 22 (16.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 22 (17.6%) | 0.2109 | - |

| 30 mm | 3 (2.2%) | 1 (9.1%) | 2 (1.6%) | 0.2251 | 6.15 (0.51, 73.84) |

| 38 mm | 71 (52.2%) | 7 (63.6%) | 64 (51.2%) | 0.5362 | 1.67 (0.46, 5.98) |

| 40 mm | 34 (25.0%) | 4 (36.4%) | 30 (24.0%) | 0.4666 | 1.81 (0.50, 6.61) |

| 60 mm | 11 (8.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (8.8%) | 0.5993 | - |

| 90 mm | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0.9999 | - |

| Needle thickness | |||||

| 30 G | 22 (16.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 22 (17.6%) | 0.2109 | - |

| 29 G | 106 (77.9%) | 11 (100.0%) | 95 (76.0%) | 0.1217 | - |

| 27 G | 11 (8.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (8.8%) | 0.5993 | - |

| Insertion depth | |||||

| Subcutaneous | 33 (24.3%) | 2 (18.2%) | 30 (24.8%) | 0.9999 | 0.67 (0.14, 3.29) |

| Myofascial | 130 (95.6%) | 9 (81.8%) | 121 (96.8%) | 0.0748 | 0.15 (0.02, 0.93) † |

| Intramuscular | 43 (36.4%) | 4 (36.4%) | 39 (31.2%) | 0.7419 | 1.26 (0.35, 4.56) |

| Manufacturer of TEA | |||||

| Dongbang | 43 (31.6%) | 4 (36.4%) | 39 (31.2%) | 0.7419 | 1.26 (0.35, 4.56) |

| Hyundae Meditech | 93 (68.4%) | 7 (63.6%) | 86 (68.8%) | 0.7419 | 0.79 (0.22, 2.87) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ha, S.; Lee, S.; Goo, B.; Kim, E.; Kwon, O.; Nam, S.-S.; Kim, J.-H. Safety of Thread-Embedding Acupuncture: A Multicenter, Prospective, Observational Pilot Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232396

Ha S, Lee S, Goo B, Kim E, Kwon O, Nam S-S, Kim J-H. Safety of Thread-Embedding Acupuncture: A Multicenter, Prospective, Observational Pilot Study. Healthcare. 2024; 12(23):2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232396

Chicago/Turabian StyleHa, Seojung, Suji Lee, Bonhyuk Goo, Eunseok Kim, Ojin Kwon, Sang-Soo Nam, and Joo-Hee Kim. 2024. "Safety of Thread-Embedding Acupuncture: A Multicenter, Prospective, Observational Pilot Study" Healthcare 12, no. 23: 2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232396

APA StyleHa, S., Lee, S., Goo, B., Kim, E., Kwon, O., Nam, S.-S., & Kim, J.-H. (2024). Safety of Thread-Embedding Acupuncture: A Multicenter, Prospective, Observational Pilot Study. Healthcare, 12(23), 2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232396