The Impact of Social Media on Children’s Mental Health: A Systematic Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What countries or regions are the primary focuses of research on the impact of SM on CMH?

- (2)

- What are the main research themes regarding the effects of SM on CMH?

- (3)

- Which SM platforms have the most significant influence on CMH?

- (4)

- What factors govern the impact of SM on CMH?

- (5)

- What unique challenges, impacts, and benefits do children encounter in their use of SM?

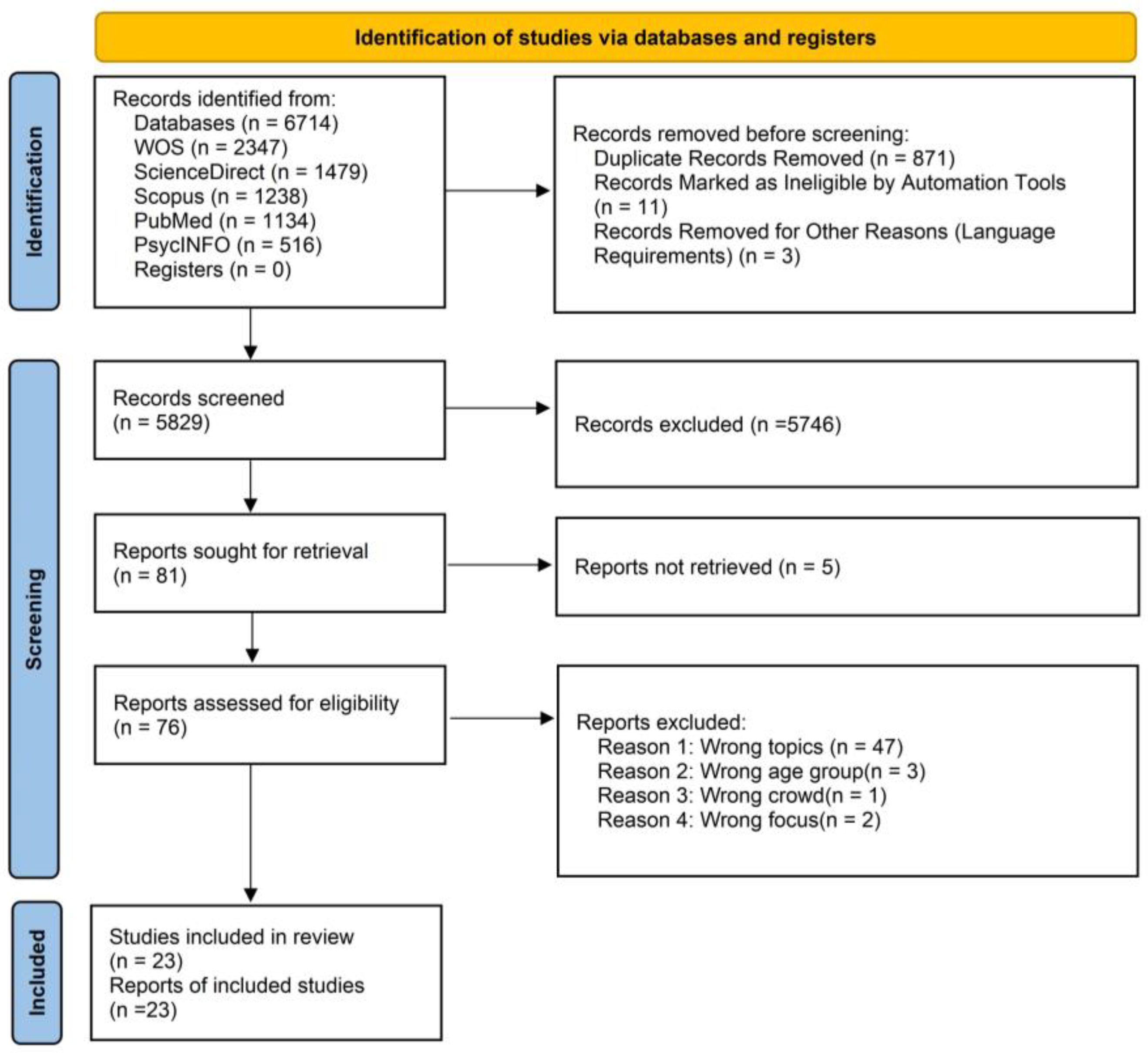

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Data Selection and Extraction

2.3. Data Charting

2.4. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

3. Results

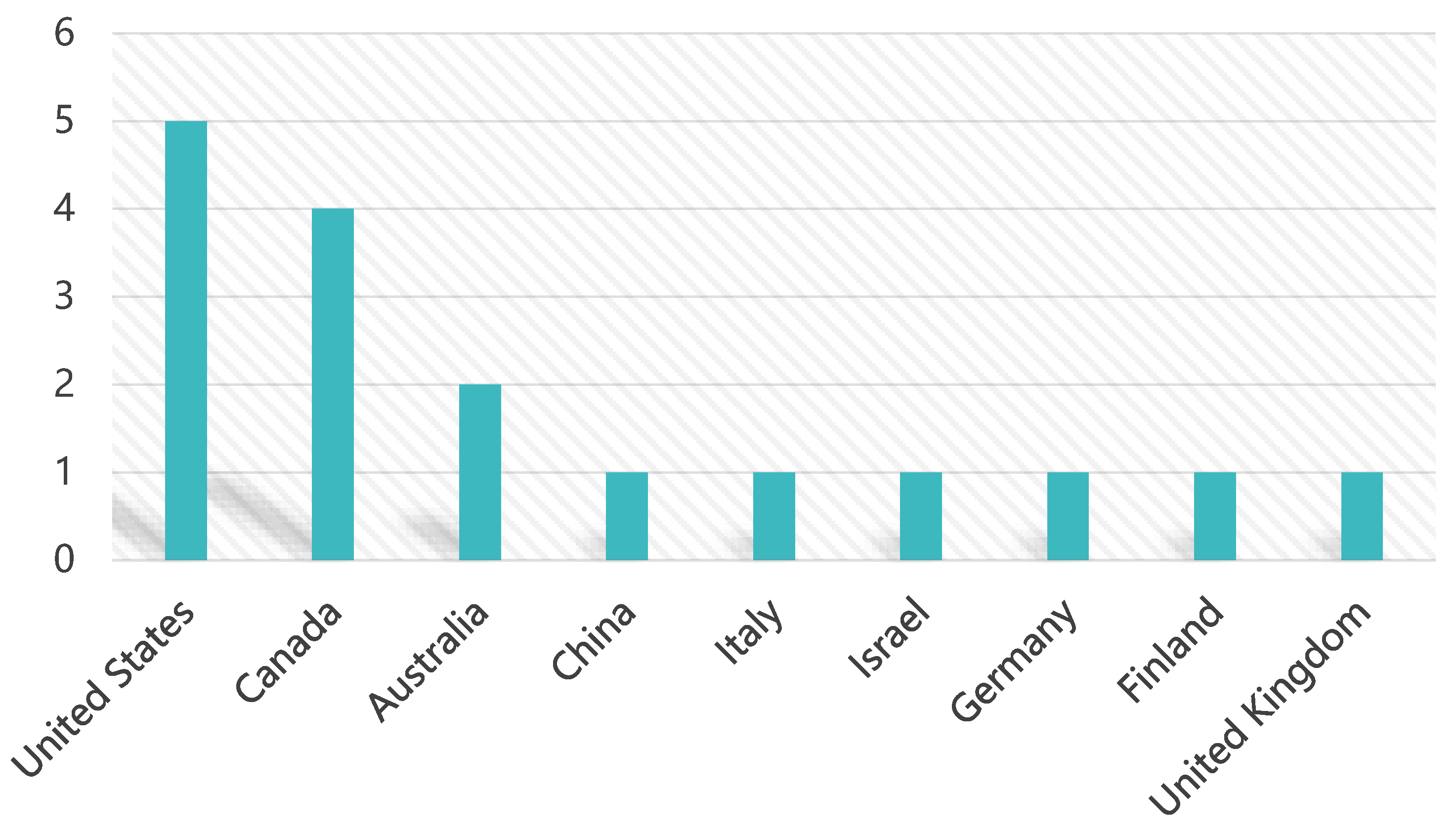

3.1. Geographical and Sample Characteristics

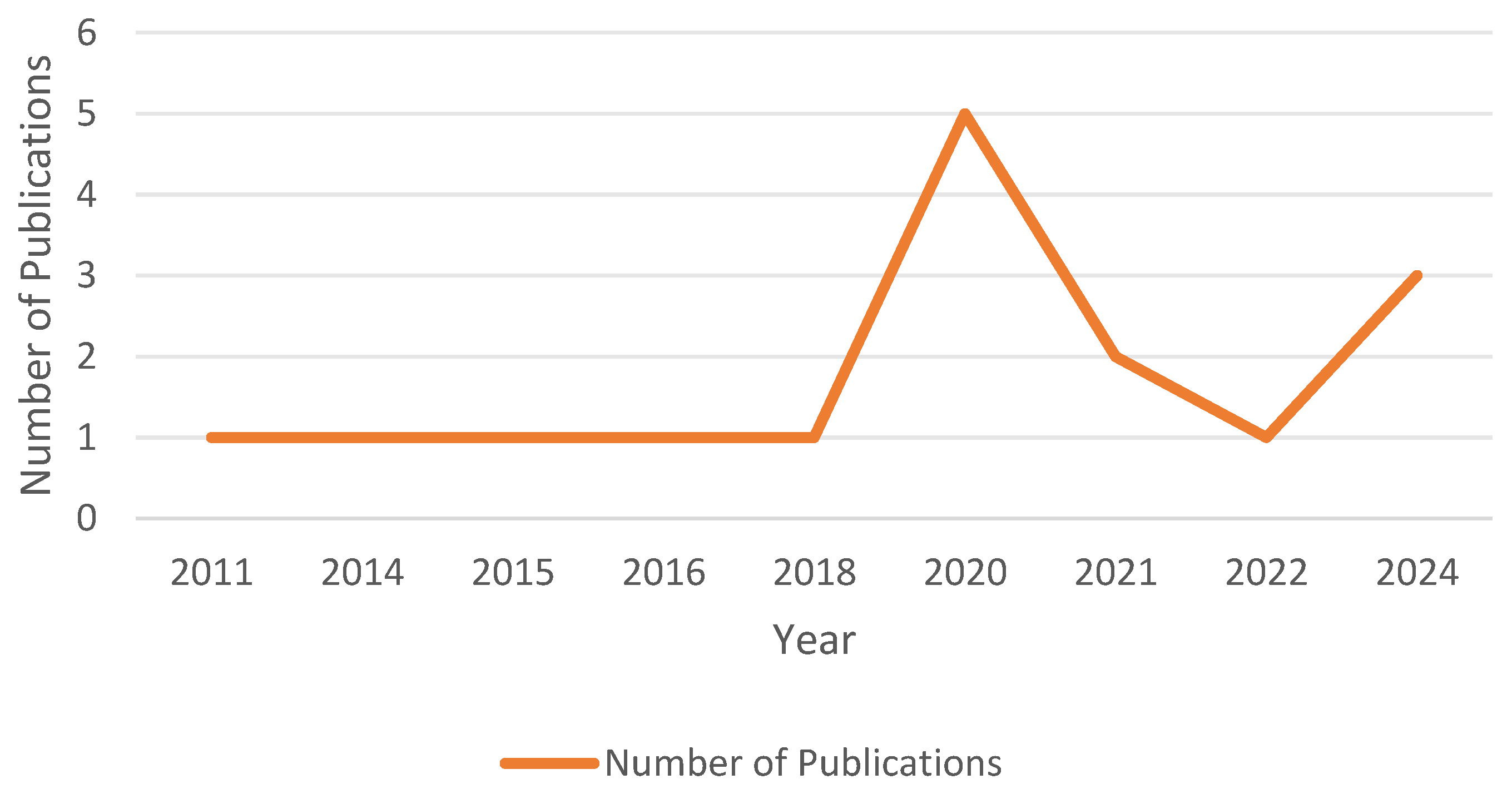

3.2. Year of Publications

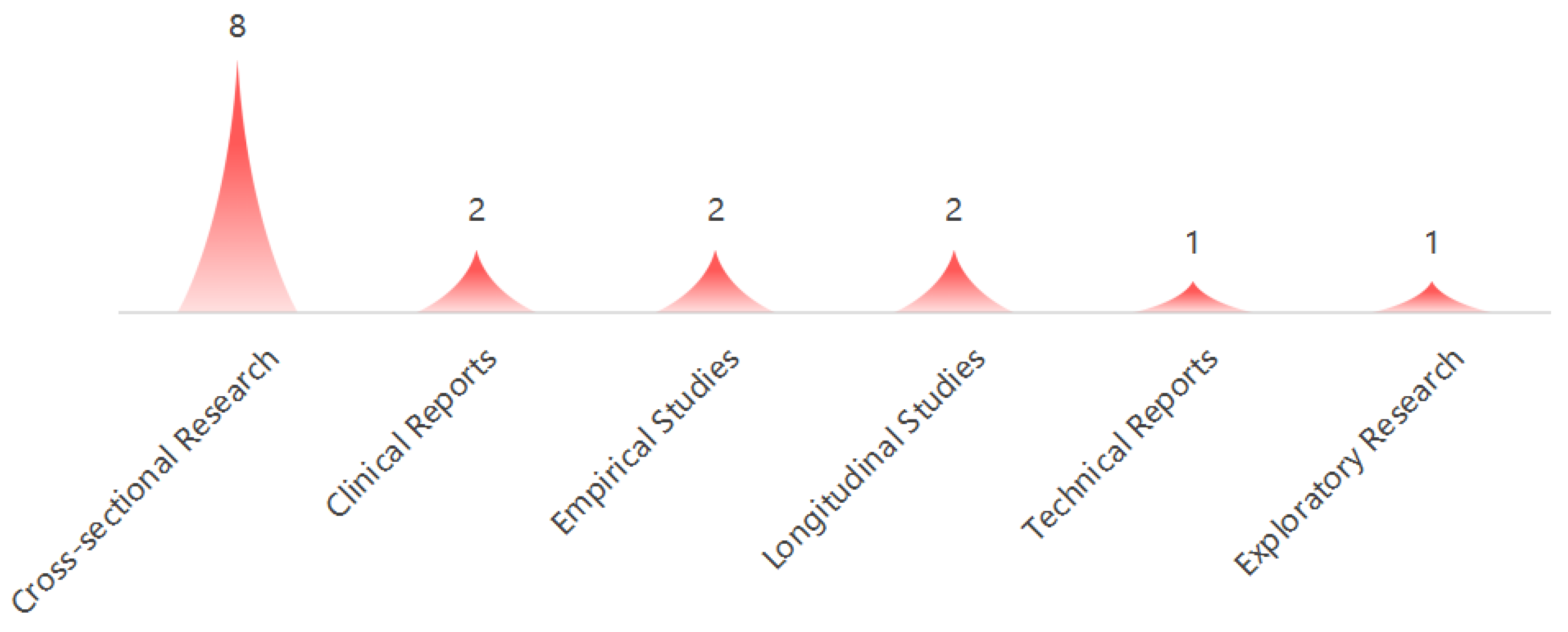

3.3. Types of Studies

3.4. Research Topics

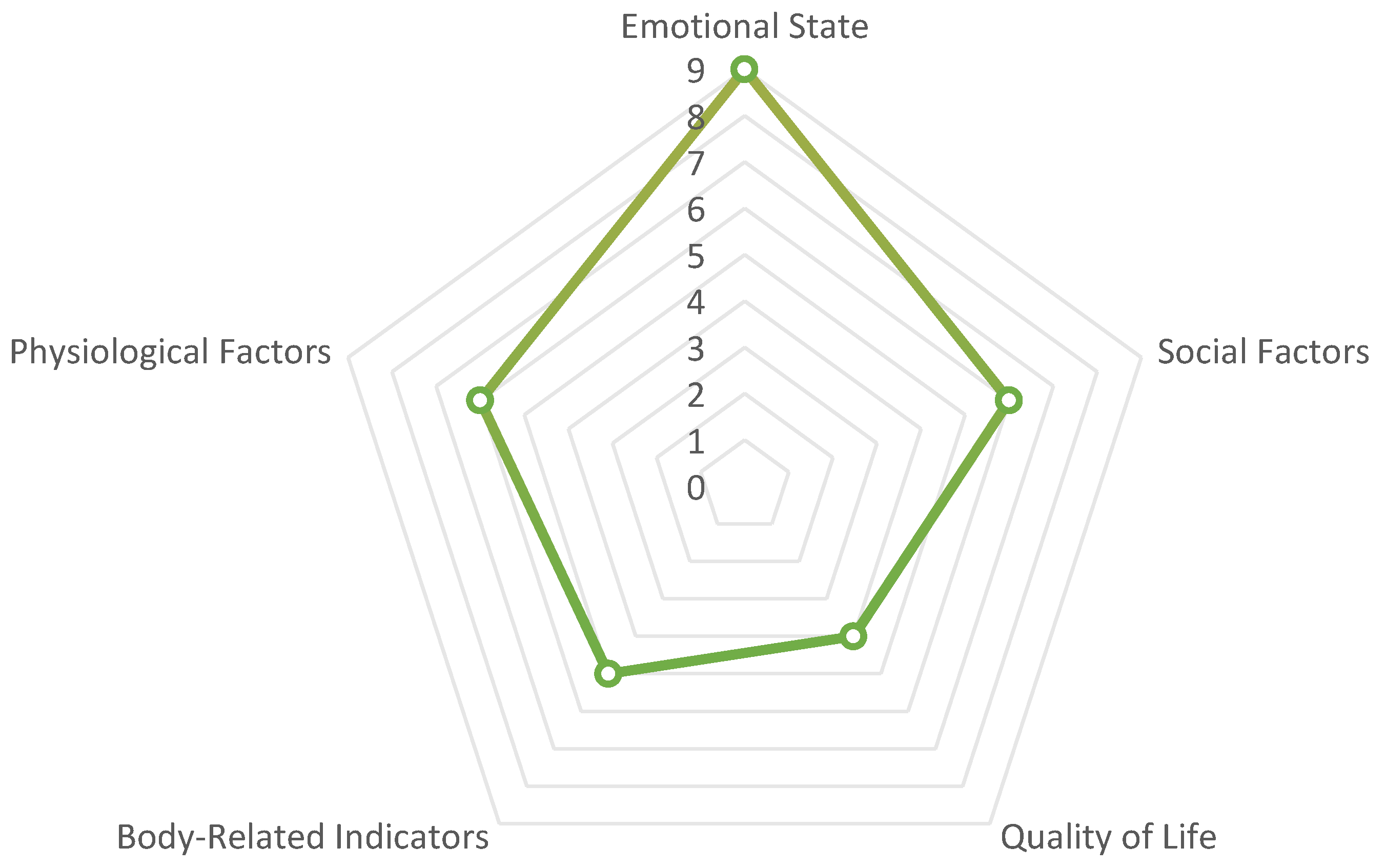

3.5. Indicators of the Impact of SM on CMH

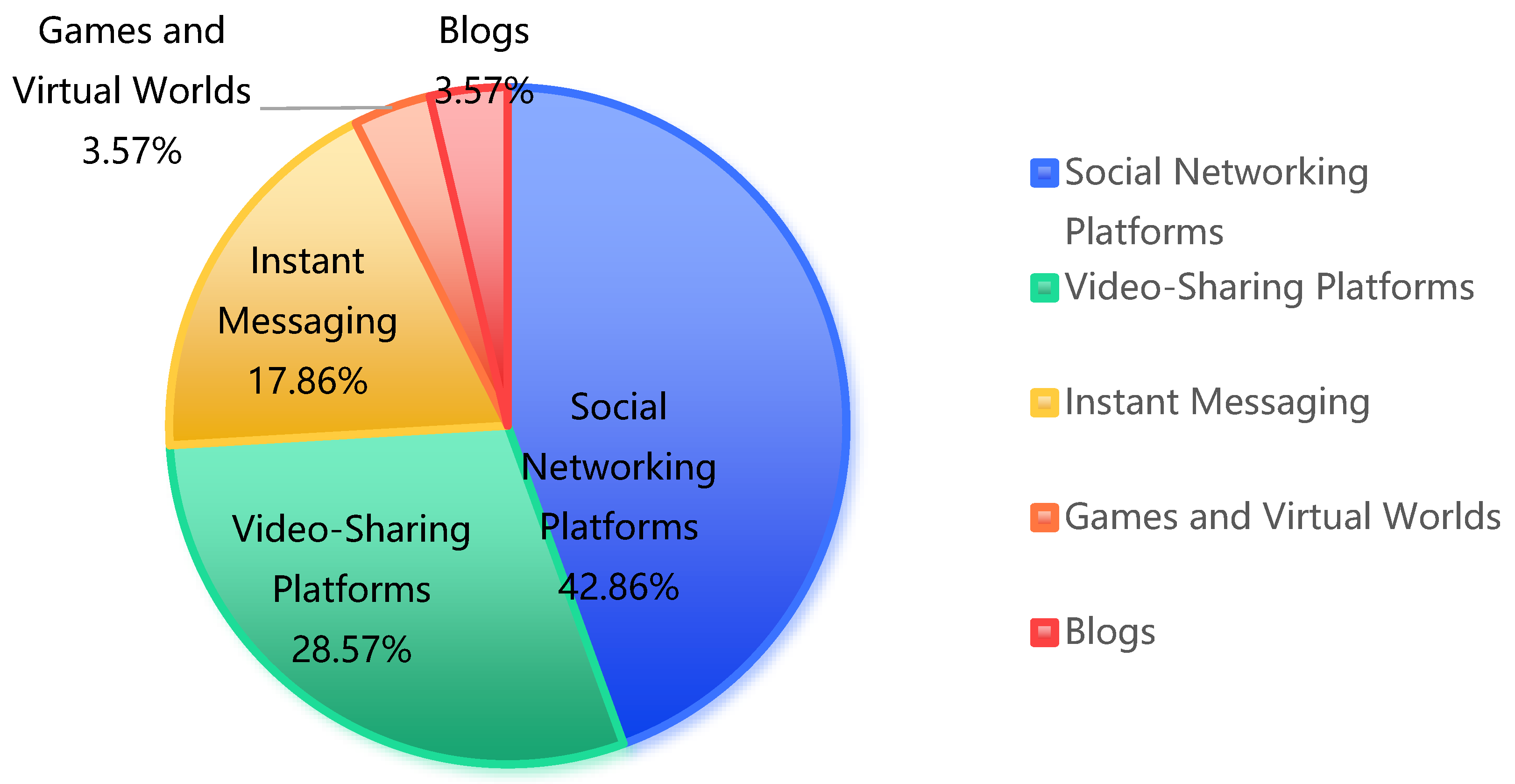

3.6. SM Platforms

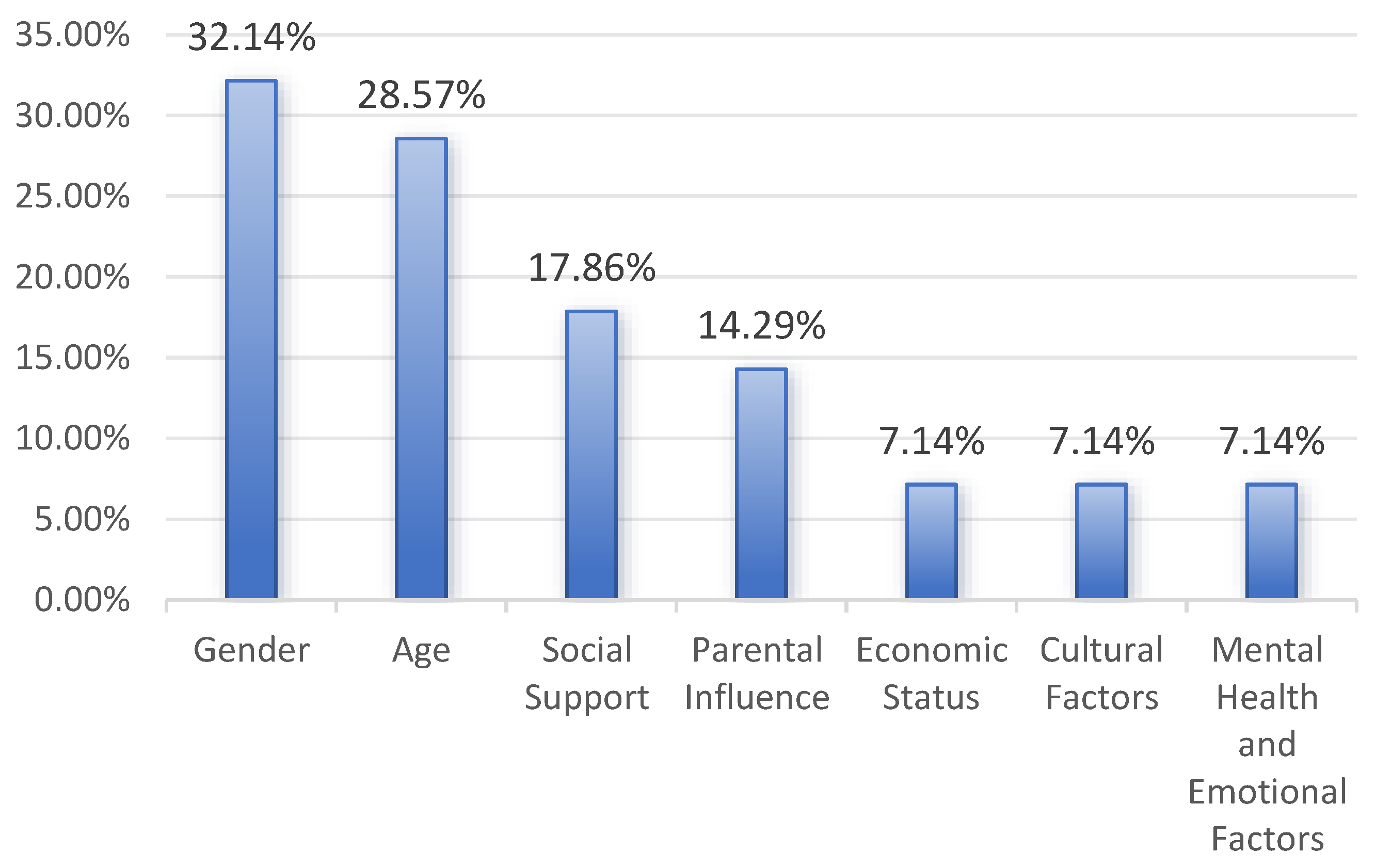

3.7. Factors and Influences

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings and Results of Studies

4.2. SM and Family, Social Support

4.3. SM Use and Subjective Well-Being

4.4. Roles of Parents and Educators

4.5. Implications for Mental Health Professionals and Practitioners

4.6. Short-Term Effects, Addiction Mechanisms, and Individual Differences

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author/Year | Type of Study | Number of Database | Sample Age Range | Theme | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghali et al. (2023) [38] | Systematic Review | 4 | 6–18 years | Internet gaming disorder and SM use | 1. Less than five databases used. 2. Focused on internet gaming disorder across themes. Short literature year span. |

| Hilty et al. (2023) [35] | Scoping Review | 11 | <25 years | Mental health | 1. Large age range, focusing on adolescents and adults. Insufficient literature timeliness. |

| Bozzola et al. (2022) [31] | Scoping Review | 1 | Not specified | Potential risks of SM use | 1. Less than five databases used. 2. Short literature year span, mainly focused on the pandemic period. 3. Theme only focuses on negative impacts, not comprehensive. Sample age range not specified. |

| McCrae et al. (2017) [32] | Systematic Review | 3 | Not specified | Depression | 1. Did not provide the number of databases. 2. Theme only focuses on depression, not comprehensive. 3. Sample age range not specified. 4. Insufficient literature timeliness. Did not specify the literature search year span. |

| Piteo et al. (2020) [33] | Systematic Review | 4 | 5–18 years | Mental health | 1. Less than five databases used. Insufficient literature timeliness. |

| Montag et al. (2024) [37] | Systematic Review | Not provided | Not specified | Addictive use issues | 1. Did not provide the number of databases 2. Theme only focuses on addictive use issues, not comprehensive. 3. Did not specify the literature search year span. Did not provide literature-screening and inclusion criteria. |

| Richards et al. (2015) [34] | Literature Review | 3 | 5–14 years | Mental health | 1. Less than five databases used. Insufficient literature timeliness. 2. Did not specify the literature search year span. Did not provide literature-screening and inclusion criteria. |

Appendix B. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist

| SECTION | ITEM | PRISMA-ScR CHECKLIST ITEM | REPORTED ON PAGE |

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | Cover page |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 1–3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 3 |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | 3–4 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | 4–5 |

| Information sources * | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 3 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 3–5 |

| Selection of sources of evidence † | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 3–5 |

| Data-charting process ‡ | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 5 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 3–5 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence § | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of the included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | 3–5 |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 5 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of the sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 5–6 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present the characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 5–15 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on the critical appraisal of the included sources of evidence (see item 12). | 15–20 |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 15–20 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 15–20 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 21–23 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 23 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 23 |

| FUNDING | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | Not applicable |

| JBI = Joanna Briggs Institute; PRISMA-ScR = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews. * Where sources of evidence (see second footnote) are compiled from, such as bibliographic databases, social media platforms, and Web sites. † A more inclusive/heterogeneous term used to account for the different types of evidence or data sources (e.g., quantitative and/or qualitative research, expert opinion, and policy documents) that may be eligible in a scoping review as opposed to only studies. This is not to be confused with information sources (see first footnote). ‡ The frameworks by Arksey and O’Malley (6) and Levac and colleagues (7) and the JBI guidance (4, 5) refer to the process of data extraction in a scoping review as data charting. § The process of systematically examining research evidence to assess its validity, results, and relevance before using it to inform a decision. This term is used for items 12 and 19 instead of “risk of bias” (which is more applicable to systematic reviews of interventions) to include and acknowledge the various sources of evidence that may be used in a scoping review (e.g., quantitative and/or qualitative research, expert opinion, and policy document). | |||

References

- Fazil, A.W.; Hakimi, M.; Akrami, K.; Akrami, M.; Akrami, F. Exploring the Role of Social Media in Bridging Gaps and Facilitating Global Communication. Stud. Media Journal. Commun. 2024, 2, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S.; Mascheroni, G.; Staksrud, E. European research on children’s internet use: Assessing the past and anticipating the future. New Media Soc. 2017, 20, 1103–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitsko, R.H.; Claussen, A.H.; Lichstein, J.; Black, L.I.; Jones, S.E.; Danielson, M.L.; Hoenig, J.M.; Jack, S.P.D.; Brody, D.J.; Perou, R. Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2013–2019. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. (MMWR) 2022, 71, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C.; Lampe, C. The benefits of Facebook “friends”: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2007, 12, 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carrión, R.; Villarejo-Carballido, B.; Villardón-Gallego, L. Children and Adolescents Mental Health: A Systematic Review of Interaction-Based Interventions in Schools and Communities. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.; Caldwell PH, Y.; Go, H. Impact of social media on adolescent mental health. J. Adolesc. 2015, 44, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Meier, A.; Beyens, I. Social Media Use and Its Impact on Adolescent Mental Health: An Umbrella Review of the Evidence. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edosomwan, S.; Prakasan, S.K.; Kouame, D.; Watson, J.; Seymour, T. The history of social media and its impact on business. J. Appl. Manag. Entrep. 2011, 16, 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, P.C.-I.; Jiang, W.; Pu, G.; Chan, K.-S.; Lau, Y. Social media engagement in two governmental schemes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Macao. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huk, T. Use of Facebook by children aged 10-12. Presence in social media despite the prohibition. New Educ. Rev. 2016, 46, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin Kent, M.; Bagnato, M.; Amson, A.; Remedios, L.; Pritchard, M.; Sabir, S.; Gillis, G.; Pauzé, E.; Vanderlee, L.; White, C. #junkfluenced: The marketing of unhealthy food and beverages by social media influencers popular with Canadian children on YouTube, Instagram and TikTok. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2024, 21, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, L.B.; Fortkamp, M.; Silva, T.O.; de Souza, V.C.R.P.; Machado, A.A.V.; de Souza, J.C.R.P. Excessive use of social media related to mental health and decreased sleep quality in students. Rev. Eletrônica Acervo Saúde. 2023, 23, e13030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Ye, Z.; Lyu, R. Detecting Student Depression on Weibo Based on Various Multimodal Fusion Methods. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Signal Processing and Machine Learning, Chicago, IL, USA, 15–22 January 2024; Volume 13077, pp. 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. Time spent on social network sites and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, H.L.; Angold, A. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosol-ogy, and epidemiology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Zhou, F.-J.; Niu, G.-F.; Fan, C.-Y.; Zhou, Z.-K. The Association between Cyberbullying Victimization and Depression among Children: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, A.D.; Hoyniak, C.; McQuillan, M.E.; Molfese, V.; Bates, J.E. Screen use before bedtime: Consequences for nighttime sleep in young children. Infant Behav. Dev. 2021, 62, 101522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, E.J.; Egger, H.; Angold, A. 10-year research update review: The epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2005, 44, 972–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauricella, A.R.; Cingel, D.P.; Blackwell, C.; Wartella, E.; Conway, A. The mobile generation: Youth and adolescent ownership and use of new media. Commun. Res. Rep. 2014, 31, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kross, E.; Verduyn, P.; Demiralp, E.; Park, J.; Lee, D.S.; Lin, N.; Shablack, H.; Jonides, J.; Ybarra, O. Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K. Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawole, O.A.; Srivastava, T.; Fasano, C.; Feemster, K.A. Evaluating variability in immunization requirements and policy among US colleges and universities. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiglic, N.; Viner, R.M. Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shensa, A.; Sidani, J.E.; Lin, L.Y.; Bowman, N.D.; Primack, B.A. Social media use and perceived emotional support among US young adults. J. Community Health 2016, 41, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, H.; Gerlach, A.L.; Crusius, J. The interplay between social comparisons, envy, and narcissism on Facebook: A vicious cycle? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 110, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman-Munick, S.M.; Gordon, A.R.; Guss, C. Adolescent body image: Influencing factors and the clinician’s role. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2020, 32, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaess, M. Social media use and its impact on adolescent mental health: An ecosystemic perspective. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2020, 33, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancellor, S.; De Choudhury, M. Methods in predictive techniques for mental health status on social media: A critical review. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzola, E.; Spina, G.; Agostiniani, R.; Barni, S.; Russo, R.; Scarpato, E.; Di Mauro, A.; Di Stefano, A.V.; Caruso, C.; Corsello, G.; et al. The Use of Social Media in Chil-dren and Adolescents: Scoping Review on the Potential Risks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, N.; Gettings, S.; Purssell, E. Social Media and Depressive Symptoms in Childhood and Adolescence: A Sys-tematic Review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2017, 2, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piteo, E.M.; Ward, K. Review: Social networking sites and associations with depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents—A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2020, 25, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, D.; Caldwell, P.H.; Go, H. Impact of social media on the health of children and young people. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2015, 51, 1152–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilty, D.M.; Stubbe, D.; McKean, A.J.; Hoffman, P.E.; Zalpuri, I.; Myint, M.T.; Joshi, S.V.; Pakyurek, M.; Li, S.T. A scoping review of social media in child, adolescents and young adults: Research findings in depression, anxiety and other clinical challenges. BJPsych Open 2023, 9, e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montag, C.; Demetrovics, Z.; Elhai, J.D.; Grant, D.; Koning, I.; Rumpf, H.J.; Spada, M.M.; van den Eijnden, R. Problematic social media use in childhood and adolescence. Addict. Behav. 2024, 153, 107980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghali, S.; Afifi, S.; Suryadevara, V.; Habab, Y.; Hutcheson, A.; Panjiyar, B.K.; Davydov, G.G.; Nashat, H.; Nath, T.S. A Systematic Review of the Association of Internet Gaming Disorder and Excessive Social Media Use with Psychiatric Comorbidities in Children and Adolescents: Is It a Curse or a Blessing? Cureus 2023, 15, e43835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid Chassiakos, Y.L.; Radesky, J.; Christakis, D.; Moreno, M.A.; Cross, C.; Hill, D.; Ameenuddin, N.; Hutchinson, J.; Levine, A.; Boyd, R.; et al. Children and adolescents and Digital Media. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20162593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The Prisma statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Tetzlaff, J.; Tricco, A.C.; Sampson, M.; Altman, D.G. Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2009, 4, e447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J.; Magson, N.R.; Rapee, R.M.; Johnco, C.J.; Oar, E.L. The use of social media by Australian preadoles-cents and its links with Mental Health. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 1304–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donelle, L.; Facca, D.; Burke, S.; Hiebert, B.; Bender, E.; Ling, S. Exploring Canadian children’s social media use, digital literacy, and quality of life: Pilot cross-sectional Survey Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e18771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, N.; Borraccino, A.; Charrier, L.; Berchialla, P.; Dalmasso, P.; Caputo, M.; Lemma, P. Cyberbullying and problematic social media use: An insight into the positive role of social support in adolescents—Data from the health behaviour in school-aged children study in Italy. Public Health 2021, 199, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keeffe, G.S.; Clarke-Pearson, K. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.L.; King, N.; Gariépy, G.; Michaelson, V.; Canie, O.; King, M.; Craig, W.; Pickett, W. Adolescent social media use and its association with relationships and connections: Canadian Health Behaviour in School-aged Children, 2017/2018. Health Rep. 2022, 33, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Cao, M.; Niu, G.; Zhou, Z. The relationship between social network site use and depres-sion among children: A moderated mediation model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2024, 157, 107419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshani, A.; Kor, A.; Bar, S. The impact of social media use on psychiatric symptoms and well-being of children and adolescents in the post-COVID-19 era: A four-year longitudinal study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 4013–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Heilmann, K.; Moor, I. The good, the bad and the ugly: Die Beziehung zwischen sozialer medi-ennutzung, subjektiver Gesundheit und Risikoverhalten im kindes- und jugendalter. Das Gesundheitswesen 2020, 83, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, H.; Kokkonen, M.; Hietajärvi, L.; Lyyra, N.; Paakkari, L. Social Media Threats and health among adolescents: Evidence from the health behaviour in school-aged children study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2024, 18, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.L. Social Media: Anticipatory guidance. Pediatr. Rev. 2020, 41, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J.; Magson, N.R.; Johnco, C.J.; Oar, E.L.; Rapee, R.M. Parental control of the time preadolescents spend on social media: Links with preadolescents’ social media appearance comparisons and mental health. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1456–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J.M. New findings from the health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) survey: Social Media, Social Determinants, and mental health. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, S1–S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga, H.; Lewis, R.F. Frequent use of social networking sites is associated with poor psychological functioning among children and adolescents. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twigg, L.; Duncan, C.; Weich, S. Is social media use associated with Children’s well-being? results from the UK household longitudinal study. J. Adolesc. 2020, 80, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yust, K.-M. Digital Power: Exploring the effects of social media on children’s spirituality. Int. J. Child. Spiritual. 2014, 19, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riehm, K.E.; Feder, K.A.; Tormohlen, K.N.; Crum, R.M.; Young, A.S.; Green, K.M.; Pacek, L.R.; La Flair, L.N.; Mojtabai, R. Associations between time spent using social media and internalizing and externalizing problems among US youth. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napoli, P.M. User Data as public resource: Implications for social media regulation. Policy Internet 2019, 11, 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swist, T.; Collin, P.; McCormack, J.; Third, A. Social Media and the Wellbeing of Children and Young People: A Literature Review; Commission for Children and Young People: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2015; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.P.; Chang, S.C. Leverage Between the Buffering Effect and the Bystander Effect in Social Networking. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Formula |

|---|---|

| Web of Science | TS = (“social media” OR “new media” OR “online platform”) AND TS = (“children” OR “minors” OR “child”) AND TS = (“mental health” OR “well-being”) AND PY = (2014–2024) |

| ScienceDirect | (“social media” OR “new media” OR “online platform”) AND (“children” OR “minors” OR “child”) AND (“mental health” OR “well-being”) AND (2014 TO 2024) |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY (“social media” OR “new media” OR “online platform”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“children” OR “minors” OR “child”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“mental health” OR “well-being”) AND PUBYEAR > 2013 AND PUBYEAR < 2025 |

| PubMed | (“social media” OR “new media” OR “online platform”) AND (“children” OR “minors” OR “child”) AND (“mental health” OR “well-being”) AND (2014–2024) |

| PsycINFO | ((“social media” or “new media” or “online platform”) and (“children” or “minors” or “child”) and (“mental health” or “well-being”)).mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] limit 2 to yr = “2014–2024” |

| PICO Elements | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population (P) | Children aged 6–13 years, healthy individuals | Children with medical conditions or outside age range (>13 or <6) |

| Intervention (I) | Impact of social media on mental health | Studies not focusing on social media or related topics |

| Comparison (C) | Not applicable (no specific control group) | N/A |

| Outcome (O) | Psychological well-being, emotional impact, behavioral changes | Studies without a focus on mental health outcomes |

| Type of Study | Empirical research | Literature reviews, book chapters, theses, etc. |

| Publication Date | Published between 2014 and 2024 | Published outside the 2014–2024 range |

| Language | Full text in English | Full text in other languages |

| Author/Year/Country | Type | Topic | Indicator | Sample Size | Age | Area | SM Type | Factor | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fardouly [40] 2020 Australia | Cross-sectional Research | Depression | Body Image, Pathological Eating, Depressive Symptoms, Social Anxiety | 528 | 10–12 years | Australia | Video-sharing platforms (e.g., YouTube), social networking platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram), instant messaging (e.g., Snapchat) | Gender, Appearance Comparison, Appearance Investment | SM use (especially YouTube, Instagram, and Snapchat) is linked to low body satisfaction and high eating pathology, with frequent appearance comparisons predicting declines in mental health. |

| Donelle et al. [41] 2021 Canada | Cross-sectional Research | Digital Literacy | Emotional State, Social Interaction | 42 | 6–10 years | Canada | Video-sharing platforms (e.g., YouTube), social networks (e.g., Facebook, Instagram), instant messaging (e.g., Snapchat) | Age, Gender, Type of SM Platform Used, Device Type | 57% of children use SM, with YouTube being the most popular; half share personal content but lack privacy awareness, posing potential privacy risks. |

| Marengo et al. [42] 2021 Italy | Cross-sectional Research | Cyberbullying | Self-esteem, Depression, Anxiety, Social Support | 3022 | 11, 13, 15 years | Italy | Not specified | Gender, Age, Social Support (Family, School, Peers) | Girls have a higher proportion of online bullying victimization and problematic SM use, which are positively correlated, and social support can mitigate this association. |

| O’Keeffe et al. [43] 2011 United States | Clinical Reports | Social and Emotional Development | Depression, Anxiety, Severe Isolation, Suicide | Not provided | Various age groups | Not provided | Social networking platforms (e.g., Facebook, MySpace, Twitter), games and virtual worlds (e.g., Club Penguin, Second Life, The Sims), video platforms (e.g., YouTube), blogs | Parents’ Understanding of SM, Technical Ability, Communication with Children | SM offers opportunities for social interaction and emotional expression but also presents issues such as online bullying and privacy violations, requiring parental guidance and medical education. |

| Wong et al. [44] 2022 Canada | Cross-sectional Research | Interpersonal Relationships and Social Skills | Relationship Support, Isolation, Self-esteem | 17,149 | 11–15 years | Canada | Video-sharing platforms (e.g., YouTube), social networks (e.g., Facebook), instant messaging (e.g., Snapchat) | Age, Gender, Household Economic Status | Healthy SM use strengthens friendships, while problematic use leads to poor family relationships and social isolation. |

| Chassiakos et al. [37] 2016 United States | Technical Reports | Depression | Sleep, Attention, Learning, Obesity, Depression | Not provided | 6–18 years | Not provided | Video-sharing platforms (e.g., YouTube), social networks (e.g., Facebook), multiplayer video games, video blogs (Vlogs), etc. | Age, Gender, Social Support, Type of SM Use, Usage Duration, Cyberbullying, Family Media Use Behavior | Digital media have a dual impact on the mental health of children and adolescents; moderate use is beneficial, while excessive use is harmful, necessitating the establishment of healthy usage plans. |

| Guo et al. [45] 2024 China | Empirical Studies | Subjective Well-being | Depressive Symptoms, Self-esteem Level, Self-compassion | 386 | 9–12 years | China | SM platforms (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, Instagram), social networking sites (e.g., WeChat Moments, Qzone, Sina Microblogs) | Self-Esteem, Self-Compassion, SNS Use Intensity and Experience | SNS use is positively correlated with depressive symptoms among children, with self-esteem and self-compassion playing regulatory roles. |

| Shoshani et al. [46] 2024 Israel | Longitudinal Studies | SM Risks | Depression, Anxiety, Psychological Distress, Life Satisfaction, Emotional State | 3697 | 8–14 years | Israel | Video-sharing platforms (e.g., YouTube), social networking platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram), short video platforms (e.g., TikTok), instant messaging (e.g., WhatsApp, Snapchat) | Social Support, Extracurricular Activities, Age, Gender | Increased SM use leads to rising mental symptoms and declining well-being among children and adolescents, which can be alleviated by social support and extracurricular activities. |

| Richter et al. [47] 2020 Germany | Cross-sectional Research | SM Threats | Health Self-assessment, Psychosomatic Symptoms, Life Satisfaction, Risk Behavior | 5094 | 11, 13, 15 years | Germany | SM platforms (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, Instagram), instant messaging (WhatsApp, Telegram, Snapchat) | Gender, Age, School Type, Immigrant Background | Frequent SM use is associated with poor self-health assessments among girls and reduced school satisfaction among boys, and is significantly related to smoking, drinking, and bullying behavior regardless of gender. |

| Lahti et al. [48] 2024 Finland | Cross-sectional Research | SM Anticipatory Guidance | Self-rated Health, Depressive Mood, Anxiety Symptoms | 2288 | 11, 13, 15 years | Finland | Not specified | Gender, Age, Emotional Intelligence, Family Support, Friend Support | Children and adolescents are often exposed to misinformation and appearance pressure on SM, and problematic use increases threat exposure; frequent exposure is linked to poor self-rated health, depression, and anxiety, while high emotional intelligence and family support can reduce threat exposure frequency. |

| Hill et al. [49] 2020 United States | Clinical Reports | Parental Control | Anxiety, Depression, Self-esteem, Sleep, Weight Management | Not provided | 0–18 years | Not provided | Social networking platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram) | Age Group Differences, Parental Monitoring Frequency, Screen Time Management, Online Social Behavior | SM have multiple impacts on children and adolescents; parental monitoring and guidance can reduce risks, and discussing SM use with doctors can improve health. |

| Fardouly et al. [50] 2018 Australia | Empirical Studies | Gender Equality | Depressive Symptoms, Appearance Satisfaction, Life Satisfaction | 284 | 10–12 years | Australia | Social networking platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram) | Parental Control Methods, Mental Health Status | The less control parents have over their children’s SM usage time, the higher the frequency of appearance comparisons among children, which is associated with poorer mental health. |

| Nagata et al. [51] 2020 United States | Cross-sectional Research | Excessive Social Networking | Life Satisfaction, Mental Health | Not provided | 11, 13, 15 years | 45 countries | Not specified | Socioeconomic Factors, Gender Equality | Low social support and problematic SM use predict low life satisfaction; mental health among children in high-income countries declines, with girls facing increased school pressure, and insufficient sleep and problematic SM use are associated with poorer well-being. |

| Sampasa-Kanyinga et al. [52] 2015 Canada | Cross-sectional Research | Subjective Well-being | Self-rated Mental Health, Psychological Distress, Suicidal Ideation | 753 | 11–18 years | Ottawa and Canada | Social networking platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, MySpace, Instagram) | Daily Social Network Usage Time, Gender, Grade, Subjective Socioeconomic Status, Parental Education Level | Students who use SNS for more than 2 h per day have a significantly increased risk of mental health issues, including poor self-esteem, psychological distress, and suicidal ideation. |

| Twigg et al. [53] 2020 United Kingdom | Longitudinal Studies | Children’s Spirituality Development | Life Satisfaction | 7596 | 10–15 years | United Kingdom | Social networking platforms (e.g., Facebook, Bebo, MySpace) | Gender, Family Support, Income | Frequent SM use is associated with changes in children’s life satisfaction, but is not the primary cause of deterioration; girls experience a more significant decline in well-being, and parental mental health, family support, and income significantly affect children’s life satisfaction. |

| Yust et al. [54] 2014 United States | Exploratory Research | Mental Health and SM Use | Spiritual Well-being, Relationship Experience, Emotional Development | Over 25,000 | Not provided | Multiple European countries | Social networking platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter), online games | Cultural Background, Depth and Frequency of Digital Cultural Participation, Emotional Bond | Digital culture influences children’s identity and relational experiences; SM can both nurture children’s mental well-being and cause emotional disorders. While active participation can enhance extroversion and empathy, it may also lead to detached attachment. |

| Region | Number of Studies | Countries/Regions in Sample | Average Age | Sample Size Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | 6 | Italy, Germany, Finland, the UK, and Multiple European Countries | 13 years | 2288–over 25,000 |

| North America | 4 | Canada | 13 years | 42–17,149 |

| Asia–Pacific | 3 | Australia, China | 10 years | 284–528 |

| Research Topics | Subtopics | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Mental Health Issues | Depression | 3 |

| Neurosis | ||

| Subjective Well-being | ||

| Digital Literacy and Risk Awareness | Digital Literacy | 3 |

| SM Risks | ||

| SM Threats | ||

| Cyberbullying and Guidance | Cyberbullying | 2 |

| SM Anticipatory Guidance | ||

| Social and Emotional Development | Social and Emotional Development | 2 |

| Interpersonal Relationships and | ||

| Social Skills | ||

| Family and Society | Parental Control | 2 |

| Gender Equality |

| Category | Indicator Items | Occurrence Counts |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional State | Depressive Symptoms, Social Anxiety, Emotional State, Anxiety, Depression, Self-esteem Level, Self-compassion, Psychological Distress, Appearance Satisfaction | 9 |

| Social Factors | Social Interaction, Social Support, Relationship Support, Isolation, Self-esteem, Severe Isolation | 6 |

| Physiological Factors | Attention, Learning, Suicide, Spiritual Well-being, Relationship Experience, Emotional Development | 6 |

| Body-Related Indicators | Body Image, Pathological Eating, Obesity, Sleep, Weight Management | 5 |

| Quality of Life | Life Satisfaction, Health Self-assessment, Risk Behavior, Mental Health | 4 |

| Platform Type | Examples | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Networking Platforms | Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, MySpace | 12 | 42.86% |

| Video-Sharing Platforms | YouTube | 8 | 28.57% |

| Instant Messaging | Snapchat, WhatsApp, Telegram | 5 | 17.86% |

| Games and Virtual Worlds | Club Penguin, Second Life, The Sims | 1 | 3.57% |

| Blogs | N/A | 1 | 3.57% |

| N | Factors/Influences | % |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | Gender | 32.14% |

| 8 | Age | 28.57% |

| 5 | Social Support (family, school, friends) | 17.86% |

| 4 | Parental Influence (understanding of SM, monitoring frequency, and control methods) | 14.29% |

| 2 | Economic Status (household and subjective economic status) | 7.14% |

| 2 | Cultural Factors (cultural background and depth of digital cultural participation) | 7.14% |

| 2 | Mental Health and Emotional Factors (emotional intelligence and mental health status) | 7.14% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, T.; Cheng, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Pang, P.C.-I.; Xia, Y.; Lau, Y. The Impact of Social Media on Children’s Mental Health: A Systematic Scoping Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2391. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232391

Liu T, Cheng Y, Luo Y, Wang Z, Pang PC-I, Xia Y, Lau Y. The Impact of Social Media on Children’s Mental Health: A Systematic Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2024; 12(23):2391. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232391

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ting, Yanying Cheng, Yiming Luo, Zhuo Wang, Patrick Cheong-Iao Pang, Yuanze Xia, and Ying Lau. 2024. "The Impact of Social Media on Children’s Mental Health: A Systematic Scoping Review" Healthcare 12, no. 23: 2391. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232391

APA StyleLiu, T., Cheng, Y., Luo, Y., Wang, Z., Pang, P. C.-I., Xia, Y., & Lau, Y. (2024). The Impact of Social Media on Children’s Mental Health: A Systematic Scoping Review. Healthcare, 12(23), 2391. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232391