Exploring Academic Emotions Using Design Thinking Applied to Elementary School Learning Stress Adaptation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the academic emotions of students in “Design Thinking Model Applied in Stress Adaptation Course”? What are the causes of these emotions?

- (2)

- Does “Design Thinking Model Applied in Stress Adaptation Course” help students relieve stress? What are the reasons for this?

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval

2.2. Participants

2.3. Study Design and Study Procedures

2.4. The “Stress Relief Design” Instructional Activities

2.5. Measures

2.6. Content Analysis

2.6.1. Academic Emotion Journals

2.6.2. The Specific Question About Stress Relief

3. Results

3.1. Academic Emotions

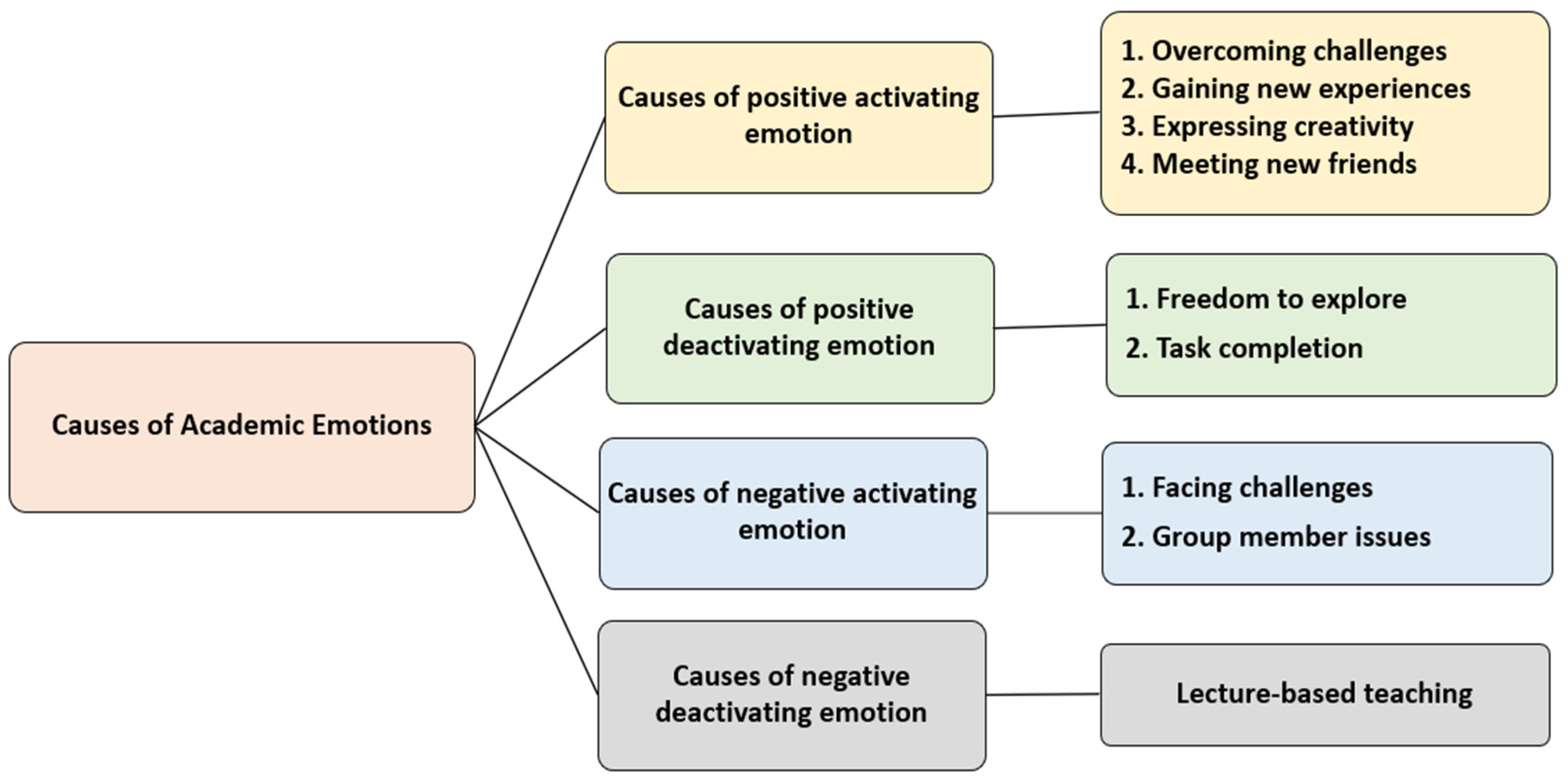

3.2. Causes of Academic Emotions

3.3. Survey on Stress Relief Levels of Agreement

4. Discussion

4.1. Exploring the Causes of the Impact of Design Thinking Curriculum on Students’ Stress Management and Academic Emotions

4.2. A Review of Data Collection Methods on the Reliability and Validity of Academic Emotional Data

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The State of Mental Health in America. 2023. Available online: https://mhanational.org/issues/state-mental-health-america (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Child and Adolescent Mental Health. The State of Children in the European Union 2024. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eu/media/2576/file/Child%20and%20adolescent%20mental%20health%20policy%20brief.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Mental Health Survey of Taiwanese High School Students. 2023. Available online: https://www.children.org.tw/publication_research/research_report/2544 (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- World Mental Health Day: True Health Comes from Mental Health. Available online: https://www.mohw.gov.tw/cp-16-76196-1.html (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Eisenberg, D.; Gollust, S.E.; Golberstein, E.; Hefner, J.L. Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2007, 77, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, Z.A.; Faizi, F.; Jalal, R.; Zadran, Z. Emotional support received moderates academic stress and mental well-being in a sample of Afghan university students amid COVID-19. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 1748–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blashill, M.M. Academic Stress and Working Memory in Elementary School Students. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bothe, D.A.; Grignon, J.B.; Olness, K.N. The effects of a stress management intervention in elementary school children. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2014, 35, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Weijer-Bergsma, E.; Langenberg, G.; Brandsma, R.; Oort, F.J.; Bögels, S.M. The effectiveness of a school-based mindfulness training as a program to prevent stress in elementary school children. Mindfulness 2014, 5, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotardi, V.A. Understanding student stress and coping in elementary school: A mixed-method, longitudinal study. Psychol. Sch. 2016, 53, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. General Guidelines of Grades 1–9 Curriculum for Elementary and Junior High School-Education Health and Physical Education; Ministry of Education: Taipei, Taiwan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Catford, J.; Nutbeam, D. Towards a definition of health education and health promotion. Health Educ. J. 1984, 43, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, D.; Richardson, C.; Mehta, R. Design thinking: A creative approach to educational problems of practice. Think. Ski. Creat. 2017, 26, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, R.; Siang, T. How to Select the Best Idea by the End of an Ideation Session. The Interaction Design Foundation. 2018. Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/how-to-select-the-best-idea-by-the-endof-an-ideation-session (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Taimur, S.; Onuki, M. Design thinking as digital transformative pedagogy in higher sustainability education: Cases from Japan and Germany. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 114, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçın, V.; Erden, Ş. The effect of STEM activities prepared according to the design thinking model on preschool children’s creativity and problem-solving skills. Think. Ski. Creat. 2021, 41, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.-Y. Integrating Gamification Into A Design Thinking Approach To Form An Inter-Disciplinary Group Creating Health Videos. J. Lib. Arts Soc. Sci. 2019, 15, 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, L.; Kroll, T.; Bruce, F.; Lim, C.; Mountain, R. Design thinking for social innovation in health care. Des. J. 2017, 20, 755–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduk, I.; Nordberg, A.; Rainio, E. Design Thinking in Healthcare Education. In Design Thinking in Healthcare: From Problem to Innovative Solutions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer, M.J.; Carter, K.; Coffey, D.S.; Goldblatt, E.; Grus, C.L.; Keskinocak, P.; Klatt, M.; Mashima, T.; Talib, Z.; Valachovic, R.W. Utilizing a systems and design thinking approach for improving well-being within health professions’ education and health care. Nam Perspect. 2019, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.-S.; Chen, G.-S. A Study of Learning Self-Efficacy of Design Thinking Applied in Elementary School Health and Physical Education Curriculum. J. Design Stud. 2024, 7, 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yvonne, T.; Bengtsson, H.; Jansson, A. Cultivating awareness at school. Effects on effortful control, peer relations and well-being at school in grades 5, 7, and 8. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2016, 37, 456–469. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M.; Albuquerque, I.; Galhardo, A.; Cunha, M.; Lima, M.P.; Palmeira, L.; Petrocchi, N.; McEwan, K.; Maratos, F.A.; Gilbert, P. Nurturing compassion in schools: A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of a Compassionate Mind Training program for teachers. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Goetz, T.; Titz, W.; Perry, R.P. Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 37, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. Emotions at school. In Handbook of Motivation at School; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009; pp. 589–618. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R.; Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. Academic emotions and student engagement. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 259–282. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, K.R. Psychological models of emotion. Neuropsychol. Emot. 2000, 137, 137–162. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R. Emotions and Learning; International Academy of Education (IAE): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Boekaerts, M.; Pekrun, R. Emotions and emotion regulation in academic settings. In Handbook of Educational Psychology; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Markopoulos, P.; Bekker, T. The Role of Children’s Emotions during Design-based Learning Activity. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2018), Funchal, Portugal, 15–17 March 2018; SciTePress Digital Library: Setúbal, Portugal, 2018; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Markopoulos, P.; Bekker, T. Children’s emotions in design-based learning: A systematic review. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2020, 29, 459–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Markopoulos, P.; Bekker, T.; Schüll, M.; Paule-Ruíz, M. EmoForm: Capturing children’s emotions during design-based learning. Proc. FabLearn 2019, 2019, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, W.E.; Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P.; Petska, K.S.; Creswell, J.D. Mixed methods research designs in counseling psychology. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-C.; Wu, P.-H. The Development of the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire-Mathematics for Taiwan Junior High School Students and the Current Situation Analysis. Psychol. Test. 2016, 63, 83–110. [Google Scholar]

Students in groups reported and explained the problems and objects they wanted to solve to their classmates. |

Students in groups expressed their ideas in the form of drawings and created prototypes. |

Students in groups showed and explained their prototype to their classmates to obtain their opinions. |

This study provides notebooks for students to write freely after class. |

The worksheet was designed based on the five steps of design thinking to guide students to develop creative design. |

Students presented the ideas generated in the Ideate step in the form of sketches. |

This student expressed her gains and feelings in the form of words and drawings on the academic emotion journals. |

Some students described the class process and academic emotions in details. For example: After interviewing others, this student were very happy to have gained a better understanding of stress. |

Some students described their feelings relatively simply and concisely. For example: This student was very happy to go on stage and report. |

| Day/Session | Steps | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1, Sessions 1–2 | Reading the textbook | Prior to the formal stress relief design teaching activity, the teacher guides students to read and comprehend the content of the “Stress Adaptation” unit in the textbook. |

| Day 1, Session 3 | The “Empathize” step | The teacher leads students to understand the objectives of the activity, instructing them to utilize interview recording methods during their free time to investigate and understand the stress sources and emotional responses of others, and to complete interview record learning sheets during their free time. |

| Day 2, Sessions 4–6 | The “Define” step | Students synthesize the data obtained from interviews, and set a scenario of stress sources and emotional responses, defining it as the target of stress relief design and completing the first part of the group learning sheet. |

| Day 3, Sessions 7–9 | The “ Ideate “ step | Students learn creative ideation methods, engage in creative brainstorming, and use visualization tools such as posters, colored pens, and sticky notes to present their ideas through writing, drawing, etc., completing the second part of the group learning sheet. |

| Day 4, Sessions 10–11 | The “Prototype” step | Students design items or methods that can relieve stress, presenting them through drawings and accompanying text, completing the second part of the group learning sheet. |

| Day 4, Session 12 | The “Test” step (part one) | Groups present their stress relief design sketches and design concepts to the audience, along with the intended users, engaging in interaction and receiving feedback or further explanations about the purpose of their work, to determine whether modifications are needed. |

| Day 4, Sessions 13–14 | The “Test” step (part two) | Groups present their revised work again and listen to feedback from others. |

| Day 5, Session 15 | Conclusions | The stress relief design teaching activity concludes. |

| Coding Category | Similar Words from Diaries |

|---|---|

| anger | angry, disgusted |

| anxiety | anxiety, irritability, nervousness, worry |

| boredom | boring |

| joy | interesting, fun, interest, like, happy |

| hope | be confident, confident, expect |

| pride | a sense of accomplishment |

| relaxation | relax |

| Parent Code | Child Code | Grandchild Code (If Applicable) | Content Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive activating emotion | Pride | Accomplishment | Today we improved Bubble Slime. I think our work was very good and we learned a lot. Thank you, Teacher! (S5(2)-91) (Test step) Today we have roughly designed some creative ways to relieve stress or the main items in item design. I think although my head is about to explode, it still feels good. (S4(3)-70) (Ideate step) |

| Hope | Confidence | During the design presentation, although some people raised questions about our design, I believe we will do better! (S4(4)-77) (Test step) Today’s class was so fun! Although it failed, it was still very interesting. There is a saying: Failure is the mother of success. I believe we will do better. (S6(3)-112) (Prototype step) | |

| Joy | Interesting | The class was very fun, as if a detective was working on a case. We integrated the stress sources and stress relief methods of the interviewees and reported on the stage. It was very interesting, and it also gave me an extra stage experience. (S5(2)-88) (Presenting) Today’s class is the most fun of all the past few days, maybe because we are designing it ourselves today! (S7(2)-125) (Prototype step) | |

| Positive deactivating emotion | Relaxation | Classes are very relaxing. (S2(4)-31) (Day 1) The teacher said that we would go on stage to give a report today. Our group did not know why we were so nervous, but as soon as we got on stage and finished speaking, I breathed a sigh of relief! (S2(2)-20) (Prototype step) | |

| Negative activating emotion | Anxiety | Nervous | Yesterday it took us a long time to complete the report. We had spent so much effort on it, but when we took the stage, we were hesitant and unable to express ourselves. This made me embarrassed and sad. I am very introverted and do not know how to express the content of the report. I hope that the following courses can help solve the stress problem. (S1(2)-4) (Presenting) Feelings: Encountering difficulties with something invented. Thoughts: It feels very hard. Everyone racked their brains for buttons. Originally we were going to make Doraemon, but I did not have three scientists, so we had to make Stress Relief Buttons. (S2(3)-27) (Ideate step) |

| Anger | Today someone kept saying that I think the balloon contains plasticizer, so I am sick, but they do not understand that plasticizer will enter the body and cause precocious puberty if it is eaten on the hand. In addition, plasticizers are not easy to wash off, so I am very unhappy. In the morning, I also discovered that someone always thought that I was saying bad things about him behind his back, but I clearly often heard him scolding me and saying bad things about me. (S6(1)-102) (Test step) | ||

| Negative deactivating emotion | Boredom | Although the process of introducing “Stress Adaptation” made me feel a bit bored, the process of group interaction was really interesting. (S1(3)-10) (Day 1) |

| Parent Code | Child Code | Content Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Causes of positive activating emotion | Overcoming challenges | When I went on stage to report today, I felt less nervous! I feel like I have made progress. My favorite moment today was when I was giving my presentation. I felt nervous before going on stage, and I also felt a great sense of accomplishment when people on stage and backstage laughed! The presentation was less tense this time. (S7(1)-119) We finally graduated! I have been on stage to report for almost five weeks, and I feel very happy that I can train my reporting skills. (S2(3)-28) In order to report on stage smoothly, our group practiced very hard after class, and finally successfully presented our work, although it was not as perfect as during practice. (S4(1)-57) |

| Gaining new experiences | The class was very fun, as if a detective was working on a case. We integrated the stress sources and stress relief methods of the interviewees and reported on the stage. It was very interesting, and it also gave me an extra stage experience. (S5(2)-88) The teacher asked us to make a small stress relief object that can make people’s stress disappear. Oh my god, it is amazing! (S2(2)-19) Today is a lesson about in-depth understanding of problems and creative ideas. This class not only allows us to use our imagination, but also allows us to understand the problem in depth. It is really interesting. (S4(4)-75) | |

| Expressing creativity | Today we improved Bubble Slime. I think our work was very good and we learned a lot. Thank you, Teacher! (S5(2)-91) Today we have roughly designed some creative ways to relieve stress or the main items in item design. I think although my head is about to explode, it still feels good. (S4(3)-70) Today’s class is the most fun of all the past few days, maybe because we are designing it ourselves today! (S7(2)-125) It was very, very fun today. Our group published toys and put a lot of emoticon stickers on the report, which was very funny. Today was very fun. At first, everyone disagreed, but then the students in the same group changed it to a lottery machine, and finally everyone accepted it. (S3(1)-38) | |

| Meeting new friends | On the first day of class, I was very excited. I met a lot of people I knew. By the way, I got to know the person opposite me named Aquarius. I was very happy. (S5(3)-94) Today is the last day of the course on Design Thinking Application and Stress Adjustment. I think it is very meaningful that I got to know one more classmate in these few days, because I rarely talk to people I do not know. I think this is the most important thing in these five days. I was forced, but I felt good after finishing it. (S4(3)-72) I was excited and I met new people and I was happy. (S5(1)-80) | |

| Causes of positive deactivating emotion | Freedom to explore | Classes are very relaxing. (S2(4)-31) |

| Task completion | The teacher said that we would go on stage to give a report today. Our group did not know why we were so nervous, but as soon as we got on stage and finished speaking, I breathed a sigh of relief! (S2(2)-20) | |

| Causes of negative activating emotion | Facing challenges | I am very nervous to go on stage to give a speech. Thoughts: Fortunately, everyone’s talk was interesting, which eased the embarrassment. (S2(3)-25) Yesterday it took us a long time to complete the report. We had spent so much effort on it, but when we took the stage, we were hesitant and unable to express ourselves. This made me embarrassed and sad. I am very introverted and do not know how to express the content of the report. I hope that the following courses can help solve the stress problem. (S1(2)-4) When I went on stage to report, I was shaking. (S7(1)-118) |

| Group member issues | Our group had a quarrel. (S7(3)-132) Every time I see him I feel very bad. (S2(2)-21) No one I know has a crying face. (S3(4)-48) The members of our group had a quarrel today! Just for a small puddle of water, I really do not understand (S7(2)-126) | |

| Causes of negative deactivating emotion | Lecture-based teaching | Although I felt a little bored when the teacher talked about stress, the group interaction process was really interesting. (S1(3)-10) But I feel a little bored! (S7(3)-129) |

| Parent Code | Child Code | Content Examples |

|---|---|---|

| High agreement | Effective stress relief methods | Most of the stress relief methods I learned here worked for me. (Q-S1(3)-1) I can learn how to truly relieve stress through design thinking. (Q-S2(1)-1) Stress relief designing can make all my stress disappear. I hope there will be courses like this in the future. (Q-S2(2)-1) |

| Design thinking as a stress release | Sometimes you have to go on stage for presentation and you can watch other groups’ stress relief designs. If you use the normal class mode, it will be boring, so it is fun this way. (Q-S2(3)-1) Because after class, when my brother hits me at home, I do not want to hit him. (Q-S2(4)-1) I have relieved stress because I feel no pressure anymore. (Q-S3(1)-1) The class is rich in content and you can learn some knowledge without any pressure. (Q-S3(2)-1) Spending time with friends helps me relieve stress. (Q-S4(1)-1) | |

| Low agreement | Classes as a source of stress | It cannot relieve stress. As long as you have to write down something or be graded, it has no stress-relieving function. (Q-S1(1)-1) I think although every activity is fun, I feel a little troublesome to write a lot of words. (Q-S1(2)-1) Because learning itself cannot relieve stress. (Q-S6(2)-1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, F.-S.; Chen, G.-S. Exploring Academic Emotions Using Design Thinking Applied to Elementary School Learning Stress Adaptation. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12212103

Lin F-S, Chen G-S. Exploring Academic Emotions Using Design Thinking Applied to Elementary School Learning Stress Adaptation. Healthcare. 2024; 12(21):2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12212103

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Fang-Suey, and Gui-Shu Chen. 2024. "Exploring Academic Emotions Using Design Thinking Applied to Elementary School Learning Stress Adaptation" Healthcare 12, no. 21: 2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12212103

APA StyleLin, F.-S., & Chen, G.-S. (2024). Exploring Academic Emotions Using Design Thinking Applied to Elementary School Learning Stress Adaptation. Healthcare, 12(21), 2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12212103

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)