The Effect of COVID-19 on Middle-Aged Adults’ Mental Health: A Mixed-Method Case–Control Study on the Moderating Effect of Cognitive Reserve

Abstract

1. Introduction

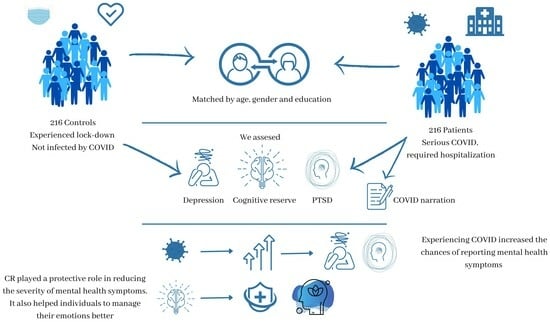

- We expect to find a significant negative effect of COVID-19 on the severity of PTSD-like symptoms and levels of reported depression, anxiety, and stress;

- We expect psychological symptoms to be significantly reduced by the individuals’ CR levels;

- We expect individuals who had COVID-19 and recovered to describe their experience differently depending on their CR level, using indicators of better emotional regulation strategies when they have a higher CR level.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Materials

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arora, T.; Grey, I.; Östlundh, L.; Lam, K.B.H.; Omar, O.M.; Arnone, D. The prevalence of psychological consequences of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 805–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Rio, C.; Collins, L.F.; Malani, P. Long-term health consequences of COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 324, 1723–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, V.; Sohaei, D.; Diamandis, E.P.; Prassas, I. COVID-19: From an acute to chronic disease? Potential long-term health consequences. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2021, 58, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M.; Blais-Rochette, C.; Kokou-Kpolou, C.K.; Noorishad, P.-G.; Mukunzi, J.N.; McIntee, S.-E.; Dalexis, R.D.; Goulet, M.-A.; Labelle, P.R. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thye, A.Y.-K.; Law, J.W.-F.; Tan, L.T.-H.; Pusparajah, P.; Ser, H.-L.; Thurairajasingam, S.; Letchumanan, V.; Lee, L.-H. Psychological Symptoms in COVID-19 Patients: Insights into Pathophysiology and Risk Factors of Long COVID-19. Biology 2022, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vindegaard, N.; Benros, M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raihan, M.M.H. Mental health consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on adult population: A systematic review. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2020, 26, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrabissa, G.; Simpson, S.G. Psychological consequences of social isolation during COVID-19 outbreak. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, S.A. Nexus between perceived job insecurity and employee work-related outcomes amid COVID-19: Attenuating effect of supervisor support. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2021, 41, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; Lee, J.; Fitzgerald, H.N.; Oosterhoff, B.; Sevi, B.; Shook, N.J. Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lithopoulos, A.; Zhang, C.-Q.; Garcia-Barrera, M.A.; Rhodes, R.E. Personality and perceived stress during COVID-19 pandemic: Testing the mediating role of perceived threat and efficacy. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, M.R.; Zarafshan, H.; Bashi, S.K.; Khaleghi, A. How to Assess Perceived Risks and Safety Behaviors Related to Pandemics: Developing the Pandemic Risk and Reaction Scale during the Covid-19 Outbreak. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2020, 15, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, S.B.; Sliwinski, M.J.; Blanchard-Fields, F. Age differences in emotional responses to daily stress: The role of timing, severity, and global perceived stress. Psychol. Aging 2013, 28, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahrens, K.; Neumann, R.; Kollmann, B.; Brokelmann, J.; Von Werthern, N.; Malyshau, A.; Weichert, D.; Lutz, B.; Fiebach, C.; Wessa, M. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health in Germany: Longitudinal observation of different mental health trajectories and protective factors. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElroy-Heltzel, S.E.; Shannonhouse, L.R.; Davis, E.B.; Lemke, A.W.; Mize, M.C.; Aten, J.; Fullen, M.C.; Hook, J.N.; Van Tongeren, D.R.; Davis, D.E. Resource loss and mental health during COVID-19: Psychosocial protective factors among US older adults and those with chronic disease. Int. J. Psychol. 2022, 57, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, L.M.; Habibović, M.; Nyklíček, I.; Smeets, T.; Mertens, G. Optimism, mindfulness, and resilience as potential protective factors for the mental health consequences of fear of the coronavirus. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 300, 113927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, R.; Albert, M.; Belleville, S.; Craik, F.I.; Duarte, A.; Grady, C.L.; Lindenberger, U.; Nyberg, L.; Park, D.C.; Reuter-Lorenz, P.A. Maintenance, reserve and compensation: The cognitive neuroscience of healthy ageing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y. What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2002, 8, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, B.; Balzarotti, S.; Greenwood, A. Using a reminiscence-based approach to investigate the cognitive reserve of a healthy aging population. Clin. Gerontol. 2019, 42, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, B.; Hamilton, A.; Telazzi, I.; Balzarotti, S. The relationship between cognitive reserve and the spontaneous use of emotion regulation strategies in older adults: A cross-sectional study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2023, 35, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusi, G.; Zanetti, M.; Ferrari, E.; Rozzini, L.; Paladino, A.; Antonietti, A.; Rusconi, M.L. CREC (CReativity in Everyday life Challenges), a new cognitive stimulation programme for patients affected by Mild Cognitive Impairment: A pilot study. In Proceedings of the 3rd MIC Conference, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 24–25 March 2019; pp. 118–120. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, B.; Antonietti, A.; Daneau, B. The relationships between cognitive reserve and creativity. A study on American aging population. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, B.; Fusi, G.; Pabla, S.; Caravita, S.C.S. Challenge your Brain. Blogging during the COVID Lockdown as a Way to Enhance Well-Being and Cognitive Reserve in an Older Population. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2022, 21, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, I.E.; Llewellyn, D.J.; Matthews, F.E.; Woods, R.T.; Brayne, C.; Clare, L. Social isolation, cognitive reserve, and cognition in older people with depression and anxiety. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 1691–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia 2009, 47, 2015–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y.; Barnes, C.A.; Grady, C.; Jones, R.N.; Raz, N. Brain reserve, cognitive reserve, compensation, and maintenance: Operationalization, validity, and mechanisms of cognitive resilience. Neurobiol. Aging 2019, 83, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela-López, B.; Cruz-Gómez, Á.J.; Lojo-Seoane, C.; Díaz, F.; Pereiro, A.; Zurrón, M.; Lindín, M.; Galdo-Álvarez, S. Cognitive reserve, neurocognitive performance, and high-order resting-state networks in cognitively unimpaired aging. Neurobiol. Aging 2022, 117, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barulli, D.J.; Rakitin, B.C.; Lemaire, P.; Stern, Y. The influence of cognitive reserve on strategy selection in normal aging. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2013, 19, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, E.; Koyanagi, A.; Caballero, F.; Domenech-Abella, J.; Miret, M.; Olaya, B.; Rico-Uribe, L.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Haro, J.M. Cognitive reserve is associated with quality of life: A population-based study. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 87, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manly, J.J.; Schupf, N.; Tang, M.-X.; Stern, Y. Cognitive decline and literacy among ethnically diverse elders. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2005, 18, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y.; Alexander, G.E.; Prohovnik, I.; Mayeux, R. Inverse relationship between education and parietotemporal perfusion deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. Off. J. Am. Neurol. Assoc. Child Neurol. Soc. 1992, 32, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdebeeck, C.; Martyr, A.; Clare, L. Cognitive reserve and cognitive function in healthy older people: A meta-analysis. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2016, 23, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, M.; Sacker, A.; Deary, I.J. Lifetime antecedents of cognitive reserve. In Cognitive Reserve; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. 54–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi-Nasab, S.M.H.; Kormi-Nouri, R.; Nilsson, L.G. Examination of the bidirectional influences of leisure activity and memory in old people: A dissociative effect on episodic memory. Br. J. Psychol. 2014, 105, 382–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarmeas, N.; Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve and lifestyle. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2003, 25, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucci, M.; Mapelli, D.; Mondini, S. Cognitive Reserve Index questionnaire (CRIq): A new instrument for measuring cognitive reserve. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 24, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costas-Carrera, A.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, M.M.; Canizares, S.; Ojeda, A.; Martín-Villalba, I.; Primé-Tous, M.; Rodríguez-Rey, M.A.; Segú, X.; Valdesoiro-Pulido, F.; Borras, R. Neuropsychological functioning in post-ICU patients after severe COVID-19 infection: The role of cognitive reserve. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2022, 21, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devita, M.; Di Rosa, E.; Iannizzi, P.; Bianconi, S.; Contin, S.A.; Tiriolo, S.; Ghisi, M.; Schiavo, R.; Bernardinello, N.; Cocconcelli, E. Risk and protective factors of psychological distress in patients who recovered from COVID-19: The role of cognitive reserve. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 852218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tanti, A.; Conforti, J.; Bruni, S.; De Gaetano, K.; Cappalli, A.; Basagni, B.; Bertoni, D.; Saviola, D. Cognitive and psychological outcomes and follow-up in severely affected COVID-19 survivors admitted to a rehabilitation hospital. Neurol. Sci. 2023, 44, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panico, F.; Luciano, S.M.; Sagliano, L.; Santangelo, G.; Trojano, L. Cognitive reserve and coping strategies predict the level of perceived stress during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 195, 111703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaco, S.; Sousa, G.; Gonçalves, A.; Dias, A.; Andrade, C.; Pereira, D.; Aires, E.A.; Moura, J.; Silva, L.; Varela, R. Predictors of cognitive dysfunction one-year post COVID-19. Neuropsychology 2023, 37, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, M.; Rodriguez, M.; Amenedo, E.; Sanchez, J.L.; Diaz, F. Cognitive reserve, age, and neuropsychological performance in healthy participants. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2006, 29, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donders, J.; Kim, E. Effect of cognitive reserve on children with traumatic brain injury. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2019, 25, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fay, T.B.; Yeates, K.O.; Taylor, H.G.; Bangert, B.; Dietrich, A.; Nuss, K.E.; Rusin, J.; Wright, M. Cognitive reserve as a moderator of postconcussive symptoms in children with complicated and uncomplicated mild traumatic brain injury. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2010, 16, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenberg, J.; Håberg, A.K.; Follestad, T.; Olsen, A.; Iverson, G.L.; Terry, D.P.; Karlsen, R.H.; Saksvik, S.B.; Karaliute, M.; Ek, J.A. Cognitive reserve moderates cognitive outcome after mild traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niknam, F.; Samadbeik, M.; Fatehi, F.; Shirdel, M.; Rezazadeh, M.; Bastani, P. COVID-19 on Instagram: A content analysis of selected accounts. Health Policy Technol. 2021, 10, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbodo, J.N.; Onwe, E.C.; Chukwu, J.; Nwasum, C.J.; Nwakpu, E.S.; Nwankwo, S.U.; Nwamini, S.; Elem, S.; Ogbaeja, N.I. Communicating health crisis: A content analysis of global media framing of COVID-19. Health Promot. Perspect. 2020, 10, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rufai, S.R.; Bunce, C. World leaders’ usage of Twitter in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A content analysis. J. Public Health 2020, 42, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, U.; Vehling-Kaiser, U.; Schmidt, J.; Hoffmann, A.; Kaiser, F. The tumor patient in the COVID-19 pandemic–an interview-based study of 30 patients undergoing systemic antiproliferative therapy. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, P.; Agrawat, H.; Shukla, A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in patients with systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease: An interview-based survey. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 1601–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, B.; Piromalli, G.; Pins, B.; Taylor, C.; Fabio, R.A. The relationship between cognitive reserve and personality traits: A pilot study on a healthy aging Italian sample. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 2031–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez, J.C.; Alfonso-Benlliure, V.; Mayordomo, T.; Sales, A. Is age just a number? Cognitive reserve as a predictor of divergent thinking in late adulthood. Creat. Res. J. 2016, 28, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmiero, M.; Di Giacomo, D.; Passafiume, D. Can creativity predict cognitive reserve? J. Creat. Behav. 2016, 50, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, B.; Caravita, S.C.; Hayes, M. The protective role of cognitive reserve on sleeping disorders on an aging population. A cross-sectional study. Transl. Med. Aging 2023, 7, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarelli, N.; Colombo, B.; Pepe, F.; Magni, E.; Antonietti, A.; Silveri, M.C. Cognitive reserve: A multidimensional protective factor in Parkinson’s disease related cognitive impairment. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2022, 29, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Serna, E.; Andrés-Perpiñá, S.; Puig, O.; Baeza, I.; Bombin, I.; Bartrés-Faz, D.; Arango, C.; Gonzalez-Pinto, A.; Parellada, M.; Mayoral, M. Cognitive reserve as a predictor of two year neuropsychological performance in early onset first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2013, 143, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmiero, M.; Di Giacomo, D.; Passafiume, D. Creativity and dementia: A review. Cogn. Process. 2012, 13, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, D.S. The impact of event scale: Revised. In Cross-Cultural Assessment of Psychological Trauma and PTSD, Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 219–238.

- Antony, M.M.; Bieling, P.J.; Cox, B.J.; Enns, M.W.; Swinson, R.P. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychol. Assess. 1998, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A.; Chorpita, B.F.; Korotitsch, W.; Barlow, D.H. Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behav. Res. Ther. 1997, 35, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.D.; Crawford, J.R. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Boyd, R.L.; Jordan, K.; Blackburn, K. The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC2015; The University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Low, D.M.; Rumker, L.; Talkar, T.; Torous, J.; Cecchi, G.; Ghosh, S.S. Natural language processing reveals vulnerable mental health support groups and heightened health anxiety on reddit during COVID-19: Observational study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, P.; Burge, M.; Meaklim, H.; Junge, M.; Jackson, M.L. Poor sleep quality and its relationship with individual characteristics, personal experiences and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelinek, L.; Stockbauer, C.; Randjbar, S.; Kellner, M.; Ehring, T.; Moritz, S. Characteristics and organization of the worst moment of trauma memories in posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2010, 48, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoemmes, F.J.; Kim, E.S. A systematic review of propensity score methods in the social sciences. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 90–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, P.C.; Yu, A.Y.X.; Vyas, M.V.; Kapral, M.K. Applying propensity score methods in clinical research in neurology. Neurology 2021, 97, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuven, E.; Sianesi, B. PSMATCH2: Stata Module to Perform Full Mahalanobis and Propensity Score Matching, Common Support Graphing, and Covariate Imbalance Testing; Boston College Department of Economics: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R.A.; McAuley, H.; Harrison, E.M.; Shikotra, A.; Singapuri, A.; Sereno, M.; Elneima, O.; Docherty, A.B.; Lone, N.I.; Leavy, O.C. Physical, cognitive and mental health impacts of COVID-19 following hospitalisation: A multi-centre prospective cohort study. MedRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mina, F.B.; Billah, M.; Karmakar, S.; Das, S.; Rahman, M.; Hasan, M.; Acharjee, U.K. An online observational study assessing clinical characteristics and impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: A perspective study from Bangladesh. J. Public Health 2021, 31, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbehzadeh, S.; Tavahomi, M.; Zanjari, N.; Ebrahimi-Takamjani, I.; Amiri-Arimi, S. Physical and mental health complications post-COVID-19: Scoping review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 147, 110525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossell, S.L.; Neill, E.; Phillipou, A.; Tan, E.J.; Toh, W.L.; Van Rheenen, T.E.; Meyer, D. An overview of current mental health in the general population of Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from the COLLATE project. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 296, 113660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sojli, E.; Tham, W.W.; Bryant, R.; McAleer, M. COVID-19 restrictions and age-specific mental health—US probability-based panel evidence. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, M.; Stickley, A.; Sueki, H.; Matsubayashi, T. Mental health status of the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional national survey in Japan. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, X.; Castaño-Vinyals, G.; Espinosa, A.; Carreras, A.; Liutsko, L.; Sicuri, E.; Foraster, M.; O’Callaghan-Gordo, C.; Dadvand, P.; Moncunill, G. Mental health and COVID-19 in a general population cohort in Spain (COVICAT study). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 2457–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seil, K.; Yu, S.; Alper, H. A cognitive reserve and social support-focused latent class analysis to predict self-reported confusion or memory loss among middle-aged World Trade Center health registry enrollees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakesh, G.; Morey, R.A.; Zannas, A.S.; Malik, Z.; Marx, C.E.; Clausen, A.N.; Kritzer, M.D.; Szabo, S.T. Resilience as a translational endpoint in the treatment of PTSD. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 1268–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology 2002, 39, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockman, R.; Ciarrochi, J.; Parker, P.; Kashdan, T. Emotion regulation strategies in daily life: Mindfulness, cognitive reappraisal and emotion suppression. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2017, 46, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, A.; Ogden, J.; Hepper, E.G. Evaluating the impact of a time orientation intervention on well-being during the COVID-19 lockdown: Past, present or future? J. Posit. Psychol. 2022, 17, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, G. Achievement, wellbeing, and value. Philos. Compass 2016, 11, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, D.; O’Connell, E.E.; Tyson, P.; Clark-Stone, F.; Opher, S.; James, D. ‘It helps me make sense of the world’: The role of an art intervention for promoting health and wellbeing in primary care—Perspectives of patients, health professionals and artists. J. Public Health 2012, 20, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramm, J.M.; Nieboer, A.P. Social cohesion and belonging predict the well-being of community-dwelling older people. BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, B.; Edwards, A.V.; Musikanski, L. Life satisfaction, affect, and belonging in older adults. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 1205–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.F.; Russell, A.; Powers, J.R. The sense of belonging to a neighbourhood: Can it be measured and is it related to health and well being in older women? Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 2627–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, Y.; Wann, D.L.; Lock, D.; Sato, M.; Moore, C.; Funk, D.C. Enhancing older adults’ sense of belonging and subjective well-being through sport game attendance, team identification, and emotional support. J. Aging Health 2020, 32, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Song, H.; Vorderer, P. Why do people post and read personal messages in public? The motivation of using personal blogs and its effects on users’ loneliness, belonging, and well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1626–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrand, C.; Perrin, C.; Nasarre, S. Motives for regular physical activity in women and men: A qualitative study in French adults with type 2 diabetes, belonging to a patients’ association. Health Soc. Care Community 2008, 16, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.; Hocking, C.; Sandham, M. Doing, being, becoming, and belonging: Experiences transitioning from bowel cancer patient to survivor. J. Occup. Sci. 2020, 30, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, D.; Sims, T. How is a sense of well-being and belonging constructed in the accounts of autistic adults? Disabil. Soc. 2016, 31, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mock, S.E.; Fraser, C.; Knutson, S.; Prier, A. Physical leisure participation and the well-being of adults with rheumatoid arthritis: The role of sense of belonging. Act. Adapt. Aging 2010, 34, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, A. Stories as data, data as stories: Making sense of narrative inquiry in clinical education. Med. Educ. 2005, 39, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charon, R. Narrative medicine: Caring for the sick is a work of art. J. Am. Acad. PAs 2013, 26, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvåle, K.; Haugen, D.F.; Synnes, O. Patients’ illness narratives—From being healthy to living with incurable cancer: Encounters with doctors through the disease trajectory. Cancer Rep. 2020, 3, e1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alparone, F.R.; Pagliaro, S.; Rizzo, I. The words to tell their own pain: Linguistic markers of cognitive reappraisal in mediating benefits of expressive writing. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 34, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boals, A.; Klein, K. Word use in emotional narratives about failed romantic relationships and subsequent mental health. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 24, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, P.M.; Lutgendorf, S.K. Journaling about stressful events: Effects of cognitive processing and emotional expression. Ann. Behav. Med. 2002, 24, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Stone, L.D. Words of wisdom: Language use over the life span. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashokkumar, A.; Pennebaker, J.W. Social media conversations reveal large psychological shifts caused by COVID-19’s onset across US cities. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, D. Dreams about COVID-19 versus normative dreams: Trends by gender. Dreaming 2020, 30, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumontod, R.Z., III. Seeing the invisible: Extracting signs of depression and suicidal ideation from college students’ writing using LIWC a computerized text analysis. Int. J. Res. Stud. Educ. 2020, 9, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.M.; Short, S.D.; Sawyer, L.; Sweazy, S. Randomized controlled trial assessing the efficacy of expressive writing in reducing anxiety in first-year college students: The role of linguistic features. Psychol. Health 2021, 36, 1041–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tov, W.; Ng, K.L.; Lin, H.; Qiu, L. Detecting well-being via computerized content analysis of brief diary entries. Psychological Assess. 2013, 25, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrosiers, A.; Vine, V.; Kershaw, T. “RU Mad?”: Computerized text analysis of affect in social media relates to stress and substance use among ethnic minority emerging adult males. Anxiety Stress Coping 2019, 32, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patients N = 216 | Controls N = 216 | 95% CI 95% Confidence Intervals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Range: 54–66 Mean: 58.32 SD: 4.21 | Range: 54–65 Mean: 58.14 SD: 4.14 | −1.02–0.55 |

| Years of completed education | Range: 10–27 Mean: 17.25 SD: 4.25 | Range: 10–25 Mean: 16.92 SD: 4.24 | −1.09–0.44 |

| Variable | Min–Max | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | |||

| PTSD—Total score | 14–66 | 34.32 | 13.26 |

| Intrusion | 0.39–2.89 | 1.51 | 0.65 |

| Avoidance | 0.28–3 | 1.35 | 0.64 |

| Hyperarousal | 0.21–3 | 1.40 | 0.62 |

| Depression | 10–37 | 18.04 | 6.14 |

| Anxiety | 11–33 | 16.92 | 6.05 |

| Stress | 10–29 | 17.70 | 6.14 |

| Cognitive reserve | 45–106 | 76.12 | 13.43 |

| Cases | |||

| PTSD—Total score | 19–69 | 40.76 | 15.44 |

| Intrusion | 1–3 | 1.92 | 0.72 |

| Avoidance | 1–3 | 1.81 | 0.69 |

| Hyperarousal | 1–3 | 1.80 | 0.68 |

| Depression | 11–40 | 20.87 | 7.38 |

| Anxiety | 12–39 | 20.05 | 7.63 |

| Stress | 11–36 | 20.42 | 7.38 |

| Cognitive reserve | 44–122 | 81.07 | 17.19 |

| β Coefficient | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IES | |||

| COVID status PTSD total score | 6.43 | <0.0001 | 3.71–9.15 |

| COVID status Intrusion | 0.41 | <0.0001 | 0.28–0.54 |

| COVID status Avoidance | 0.45 | <0.0001 | 0.32 –0.58 |

| COVID status Hyperarousal | 0.40 | <0.0001 | 0.27–0.52 |

| DASS | |||

| COVID status Depression | 2.83 | <0.0001 | 1.55–4.12 |

| COVID status Anxiety | 3.12 | <0.0001 | 1.82–4.43 |

| COVID status Stress | 2.72 | <0.0001 | 1.51–3.94 |

| β Coefficient | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IES—PTSD, total | |||

| COVID positive/negative | 9.85 | <0.0001 | 7.98–11.71 |

| Cognitive reserve | −0.69 | <0.0001 | −0.75–−0.63 |

| IES—Intrusion | |||

| COVID positive/negative | 0.57 | <0.0001 | 0.47–0.66 |

| Cognitive reserve | −0.03 | <0.0001 | −0.04–−0.03 |

| IES—Avoidance | |||

| COVID positive/negative | 0.61 | <0.0001 | 0.53–0.70 |

| Cognitive reserve | −0.03 | <0.0001 | −0.04–−0.03 |

| IES—Hyperarousal | |||

| COVID positive/negative | 0.55 | <0.0001 | 0.47–0.64 |

| Cognitive reserve | −0.03 | <0.0001 | −0.04–−0.03 |

| DASS—Depression | |||

| COVID positive/negative | 4.40 | <0.0001 | 3.50–5.30 |

| Cognitive reserve | −0.32 | <0.0001 | −0.35–−0.29 |

| DASS—Anxiety | |||

| COVID positive/negative | 4.98 | <0.0001 | 4.26–5.70 |

| Cognitive reserve | −0.37 | <0.0001 | −0.40–−0.35 |

| DASS—Stress | |||

| COVID positive/negative | 4.03 | <0.0001 | 3.09–4.98 |

| Cognitive reserve | −0.26 | <0.0001 | −0.30–−0.23 |

| β Coefficient | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IES | |||

| COVID positive/negative PTSD total score | 5.29 | <0.0001 | 2.33–8.25 |

| COVID positive/negative Intrusion | 0.33 | <0.0001 | 0.19–0.47 |

| COVID positive/negative Avoidance | 0.35 | <0.0001 | 0.21–0.49 |

| COVID positive/negative Hyperarousal | 0.33 | <0.0001 | 0.19–0.46 |

| DASS | |||

| COVID positive/negative Depression | 1.46 | 0.038 | 0.08–2.85 |

| COVID positive/negative Anxiety | 1.91 | 0.009 | 0.47–3.34 |

| COVID positive/negative Stress | 1.90 | 0.005 | 0.58–3.22 |

| β Coefficient | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IES—PTSD, total | |||

| COVID status | 9.05 | <0.0001 | 7.00–11.11 |

| Cognitive reserve | −0.68 | <0.0001 | −0.74–−0.61 |

| IES—Intrusion | |||

| COVID status | 0.50 | <0.0001 | 0.40–0.61 |

| Cognitive reserve | −0.03 | <0.0001 | −0.04–−0.03 |

| IES—Avoidance | |||

| COVID status | 0.53 | <0.0001 | 0.44–0.63 |

| Cognitive reserve | −0.03 | <0.0001 | −0.04–−0.03 |

| IES—Hyperarousal | |||

| COVID status | 0.50 | <0.0001 | 0.41–0.59 |

| Cognitive reserve | −0.03 | <0.0001 | −0.04–−0.03 |

| DASS—Depression | |||

| COVID status | 3.22 | <0.0001 | 2.26–4.19 |

| Cognitive reserve | −0.32 | <0.0001 | −0.35–−0.29 |

| DASS—Anxiety | |||

| COVID status | 4.00 | <0.0001 | 3.20–4.79 |

| Cognitive reserve | −0.38 | <0.0001 | −0.41–−0.35 |

| DASS—Stress | |||

| COVID status | 3.32 | <0.0001 | 2.26–4.38 |

| Cognitive reserve | −0.26 | <0.0001 | −0.29–−0.22 |

| Effect of Cognitive Reserve on: | β Coefficient | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Affect | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.07–−0.001 |

| Positive Emotions | −0.02 | <0.0001 | −0.04–−0.01 |

| Negative Emotions | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.06–0.01 |

| Anxiety | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.03–0.06 |

| Anger | omitted | omitted | omitted |

| Sadness | −0.07 | <0.001 | −0.08–−0.05 |

| Affiliation | 0.12 | <001 | 0.10–0.15 |

| Achievement | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.02–0.04 |

| Reward | 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.01–0.04 |

| Risk-taking | −0.05 | <0.001 | −0.05–−0.04 |

| Focus on the past | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.02–0.001 |

| Focus on the present | 0.13 | <0.001 | 0.10–0.16 |

| Focus on the future | 0.19 | <0.001 | 0.16–0.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Colombo, B.; Fusi, G.; Christopher, K.B. The Effect of COVID-19 on Middle-Aged Adults’ Mental Health: A Mixed-Method Case–Control Study on the Moderating Effect of Cognitive Reserve. Healthcare 2024, 12, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020163

Colombo B, Fusi G, Christopher KB. The Effect of COVID-19 on Middle-Aged Adults’ Mental Health: A Mixed-Method Case–Control Study on the Moderating Effect of Cognitive Reserve. Healthcare. 2024; 12(2):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020163

Chicago/Turabian StyleColombo, Barbara, Giulia Fusi, and Kenneth B. Christopher. 2024. "The Effect of COVID-19 on Middle-Aged Adults’ Mental Health: A Mixed-Method Case–Control Study on the Moderating Effect of Cognitive Reserve" Healthcare 12, no. 2: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020163

APA StyleColombo, B., Fusi, G., & Christopher, K. B. (2024). The Effect of COVID-19 on Middle-Aged Adults’ Mental Health: A Mixed-Method Case–Control Study on the Moderating Effect of Cognitive Reserve. Healthcare, 12(2), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020163