Privacy in Community Pharmacies in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design, Participants, Setting, and Ethical Consideration

2.2. Data Collection, Data Source, and Study Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

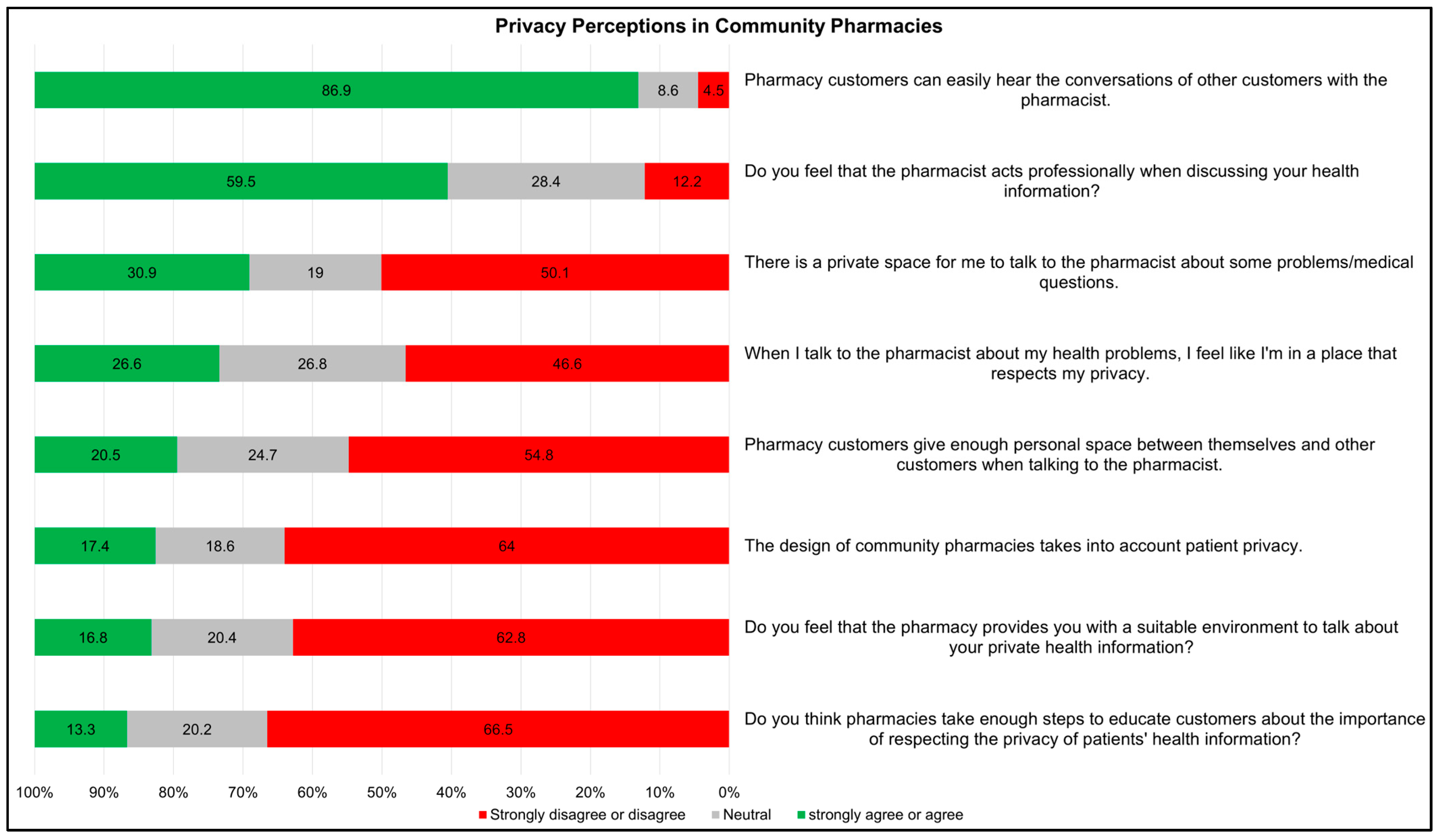

3.2. Privacy Perceptions and Practices in Community Pharmacies

3.3. Importance of Privacy and Privacy Concerns in Community Pharmacies

3.4. Patient Experiences with Privacy in Community Pharmacies

3.5. Predictors of Privacy Concerns and Breaches in Community Pharmacies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Ethical Issues in Public Health Surveillance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/255721 (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Goundrey-Smith, S. The Connected Community Pharmacy: Benefits for Healthcare and Implications for Health Policy. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dores, A.R.; Peixoto, M.; Carvalho, I.P.; Jesus, Â.; Moreira, F.; Marques, A. The Pharmacy of the Future: Pharmacy Professionals’ Perceptions and Contributions Regarding New Services in Community Pharmacies. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, F.; Tabone, F.; Azzopardi, L.M.; Gauci, M.; Zarb-Adami, M.; Serracino-Inglott, A. Consumer perception of the community pharmacist and community pharmacy services in Malta. J. Pharm. Health Serv. Res. 2010, 1, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilardo, M.L.; Speciale, A. The Community Pharmacist: Perceived Barriers and Patient-Centered Care Communication. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegegne, M.D.; Melaku, M.S.; Shimie, A.W.; Hunegnaw, D.D.; Legese, M.G.; Ejigu, T.A.; Mengestie, N.D.; Zemene, W.; Zeleke, T.; Chanie, A.F. Health professionals’ knowledge and attitude towards patient confidentiality and associated factors in a resource-limited setting: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Ethics 2022, 23, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, S.D.; Brandeis, L. The Right to Privacy. Available online: https://groups.csail.mit.edu/mac/classes/6.805/articles/privacy/Privacy_brand_warr2.html (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Data Protection. Convention 108 and Protocols—Data Protection-www.coe.int. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/data-protection/convention108-and-protocol (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Personal Data Protection and Privacy|United Nations-CEB. Available online: https://unsceb.org/privacy-principles (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Privacy, Information Technology, and Health Care. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/27297739_Privacy_Information_Technology_and_Health_Care (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Privacy in Health Care|AMA-Code. Available online: https://code-medical-ethics.ama-assn.org/ethics-opinions/privacy-health-care (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- The Protection of Personal Data in Health Information Systems—Principles and Processes for Public Health. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/341374 (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Alrasheedy, A.A. Trends, Capacity Growth, and Current State of Community Pharmacies in Saudi Arabia: Findings and Implications of a 16-Year Retrospective Study. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2023, 16, 2833–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaqeel, S.; Abanmy, N.O. Counselling practices in community pharmacies in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M.K.; Alqasoumi, A.; Hasan, S.S.; Babar, Z.-U.-D. The community pharmacy practice change towards patient-centered care in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative perspective. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.S.; Alfadl, A.A.; Hussain, A.S. Pharmaceutical Care in the Community Pharmacies of Saudi Arabia: Present Status and Possibilities for Improvement. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2016, 4, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jedai, A.; Qaisi, S.; Al-Meman, A. Pharmacy Practice and the Health Care System in Saudi Arabia. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2016, 69, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, P.P.; Fremont, A.M.; Bottrell, M.; Shugarman, L.R.; Galegher, J.; Bikson, T. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule: A Practical Guide for Researchers. Med. Care 2004, 42, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, W.; Frye, S. Review of HIPAA, Part 1: History, Protected Health Information, and Privacy and Security Rules. J. Nucl. Med. Technol. 2019, 47, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HLP-Premises Requirements. Available online: https://cpe.org.uk/national-pharmacy-services/essential-services/healthy-living-pharmacies/premises-requirements/ (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Shojaei, P.; Vlahu-Gjorgievska, E.; Chow, Y.-W. Security and Privacy of Technologies in Health Information Systems: A Systematic Literature Review. Computers 2024, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondschein, C.F.; Monda, C. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in a Research Context. In Fundamentals of Clinical Data Science; Kubben, P., Dumontier, M., Dekker, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-319-99712-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tovino, S.A. The HIPAA Privacy Rule and the EU GDPR: Illustrative Comparisons. Seton Hall Law Rev. 2017, 47, 973–993. [Google Scholar]

- Iranmanesh, M.; Yazdi-Feyzabadi, V.; Mehrolhassani, M.H. The challenges of ethical behaviors for drug supply in pharmacies in Iran by a principle-based approach. BMC Med. Ethics 2020, 21, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khojah, H.M.J. Privacy Level in Private Community Pharmacies in Saudi Arabia: A Simulated Client Survey. Pharmacol. Amp Pharm. 2019, 10, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, A.; Azad, A.K.; Abbas, S.A.; Bin Che Rose, F.Z.; Helal Uddin, A.B.M. Study on the Perception of Staff and Students of a University on Community Pharmacy Practice in Ipoh, Perak, Malaysia. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2018, 10, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, F.; Hassali, M.A.; Saleem, F.; Saeed, H.; Islam, M.; Malik, U.R.; Atif, N.; Babar, Z.-U.-D. Perspectives of community pharmacists in Pakistan about practice change and implementation of extended pharmacy services: A mixed method study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 43, 1090–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- te Paske, R.; van Dijk, L.; Yilmaz, S.; Linn, A.J.; van Boven, J.F.M.; Vervloet, M. Factors Associated with Patient Trust in the Pharmacy Team: Findings from a Mixed Method Study Involving Patients with Asthma & COPD. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2023, 17, 3391–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-T.; John, W.S.; Mannelli, P.; Morse, E.D.; Anderson, A.; Schwartz, R.P. Patient perspectives on community pharmacy administered and dispensing of methadone treatment for opioid use disorder: A qualitative study in the U.S. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2023, 18, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Consumer Attitudes towards Community Pharmacy Services in Saudi Arabia|International Journal of Pharmacy Practice|Oxford Academic. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ijpp/article/12/2/83/6137022 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Bednarczyk, R.A.; Nadeau, J.A.; Davis, C.F.; McCarthy, A.; Hussain, S.; Martiniano, R.; Lodise, T.; Zeolla, M.M.; Coles, F.B.; McNutt, L.-A. Privacy in the pharmacy environment: Analysis of observations from inside the pharmacy. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. JAPhA 2010, 50, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghamdi, K.S.; Petzold, M.; Ewis, A.A.; Alsugoor, M.H.; Saaban, K.; Hussain-Alkhateeb, L. Public perspective toward extended community pharmacy services in sub-national Saudi Arabia: An online cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seubert, L.J.; Whitelaw, K.; Boeni, F.; Hattingh, L.; Watson, M.C.; Clifford, R.M. Barriers and Facilitators for Information Exchange during Over-The-Counter Consultations in Community Pharmacy: A Focus Group Study. Pharmacy 2017, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WALW—Pharmacy Regulations 2010—Home Page. Available online: https://www.legislation.wa.gov.au/legislation/statutes.nsf/law_s42606.html (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- King, A.; Hoppe, R.B. “Best Practice” for Patient-Centered Communication: A Narrative Review. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrault, E.K.; Newlon, J.L. The effect of pharmacy setting and pharmacist communication style on patient perceptions and selection of pharmacists. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2018, 58, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, C.A. Patient-Centered Communication. Pharmacy 2018, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattingh, H.L.; Emmerton, L.; Ng Cheong Tin, P.; Green, C. Utilization of community pharmacy space to enhance privacy: A qualitative study. Health Expect. Int. J. Public Particip. Health Care Health Policy 2016, 19, 1098–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, F.R.; Hor, S.-Y.; Bajorek, B.V. Considerations of Australian community pharmacists in the provision and implementation of cognitive pharmacy services: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean ± SD or Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | 33.5 ± 12 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 254 (49.7) |

| Female | 257 (50.3) |

| Educational level | |

| Elementary School | 3 (0.6) |

| Middle school | 13 (2.5) |

| High School | 93 (18.2) |

| Bachelor’s | 236 (46.2) |

| Higher Education | 166 (32.5) |

| Occupational status | |

| Employed | 300 (58.7) |

| Not employed | 200 (39.1) |

| Retired | 11 (2.2) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 229 (44.8) |

| Married | 264 (51.7) |

| Divorced | 14 (2.7) |

| Widowed | 4 (0.8) |

| Community pharmacy visits per month | |

| Once every month or less | 308 (60.3) |

| 2–3 times a month | 164 (32.1) |

| 4 times or more a month | 39 (7.6) |

| Variable | β | Std. Error | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | z Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.007 | 0.014 | 0.993 | 0.966–1.020 | −0.53 | 0.596 |

| Sex | −0.420 | 0.234 | 0.657 | 0.414–1.036 | −1.796 | 0.072 |

| Educational level | −0.048 | 0.104 | 0.924 | 0.660–1.293 | −0.464 | 0.643 |

| Occupational status | 0.400 | 0.300 | 1.492 | 0.831–2.703 | 1.333 | 0.183 |

| Marital status | −0.085 | 0.250 | 0.919 | 0.560–1.498 | −0.34 | 0.733 |

| Frequency of community pharmacy visits | 0.005 | 0.173 | 1.005 | 0.709–1.428 | 0.031 | 0.976 |

| Private space availability | −0.313 | 0.133 | 0.758 | 0.599–0.957 | −2.327 | 0.020 * |

| Pharmacy design | 0.359 | 0.166 | 1.429 | 1.036–1.988 | −2.152 | 0.031 * |

| Importance of privacy | 0.117 | 0.168 | 1.163 | 0.925–1.464 | 1.289 | 0.197 |

| Customers give enough privacy | −0.275 | 0.126 | 0.875 | 0.683–1.121 | −1.058 | 0.290 |

| Respect privacy when speaking with a pharmacist | −0.534 | 0.225 | 0.715 | 0.542–0.945 | −2.368 | 0.018 * |

| Customers can overhear conversations | 0.146 | 0.146 | 1.278 | 0.962–1.704 | 1.687 | 0.092 |

| Pharmacist professionalism | 0.160 | 0.158 | 1.150 | 0.878–1.510 | −1.014 | 0.310 |

| Good environment for privacy | −0.353 | 0.176 | 0.703 | 0.496–0.988 | −2.009 | 0.045 * |

| Pharmacies adequately educate customers on patient privacy | 0.080 | 0.153 | 1.232 | 0.916–1.668 | 0.527 | 0.598 |

| Level of worry about privacy | 0.509 | 0.119 | 1.657 | 1.317–2.102 | 4.269 | <0.01 * |

| Asked for unnecessary personal information | 0.333 | 0.226 | 1.636 | 0.859–3.187 | 1.476 | 0.140 |

| Health information treated confidentially | −0.625 | 0.234 | 0.473 | 0.298–0.748 | −3.196 | <0.01 * |

| Previous experience of privacy breach | 1.418 | 0.418 | 4.127 | 1.886–9.821 | 3.388 | <0.01 * |

| Variable | β | Std. Error | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | z Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.017 | 0.019 | 0.983 | 0.945–1.020 | −0.901 | 0.368 |

| Sex | 0.735 | 0.316 | 2.086 | 1.133–3.927 | 2.327 | 0.020 * |

| Education level | 0.432 | 0.243 | 1.540 | 0.966–2.507 | 1.780 | 0.075 |

| Job status | −0.541 | 0.464 | 0.578 | 0.232–1.437 | 0.973 | 0.331 |

| Marital status | 0.072 | 0.336 | 1.075 | 0.551–2.063 | 0.215 | 0.830 |

| Frequency of community pharmacy visits | 0.312 | 0.429 | 1.394 | 0.915–2.110 | 0.563 | 0.103 |

| Private space availability | −0.442 | 0.181 | 0.643 | 0.444–0.907 | −2.434 | 0.015 * |

| Pharmacy design | 0.602 | 0.211 | 1.833 | 1.174–2.907 | 2.849 | <0.01 * |

| Importance of privacy | −0.038 | 0.170 | 0.963 | 0.697–1.359 | −0.224 | 0.823 |

| Customers give enough privacy | −0.054 | 0.198 | 0.767 | 0.535–1.087 | −0.270 | 0.787 |

| Respect privacy when speaking with a pharmacist | −0.180 | 0.190 | 0.835 | 0.569–1.206 | −0.944 | 0.345 |

| Customers can overhear conversations | 0.154 | 0.162 | 1.166 | 0.786–1.768 | 0.947 | 0.344 |

| Pharmacist professionalism | −0.303 | 0.167 | 0.739 | 0.531–1.024 | −1.816 | 0.069 |

| Good environment for privacy | 0.408 | 0.241 | 1.567 | 0.957–2.573 | 1.697 | 0.074 |

| Pharmacies adequately educate customers on patient privacy | −0.485 | 0.227 | 0.615 | 0.392–0.956 | −2.142 | 0.032 * |

| Level of worry about privacy | 0.107 | 0.168 | 1.114 | 0.802–1.552 | 0.642 | 0.520 |

| Asked for unnecessary personal information | 1.697 | 0.322 | 5.460 | 2.919–10.371 | 5.265 | 0.010 * |

| Avoiding discussion with pharmacist due to privacy concerns | 1.456 | 0.396 | 4.291 | 2.038–9.740 | 3.675 | <0.01 * |

| Health information treated confidentially | −0.202 | 0.353 | 0.817 | 0.403–1.620 | −0.573 | 0.567 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alrasheed, M.A.; Alfageh, B.H.; Almohammed, O.A. Privacy in Community Pharmacies in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1740. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171740

Alrasheed MA, Alfageh BH, Almohammed OA. Privacy in Community Pharmacies in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2024; 12(17):1740. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171740

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlrasheed, Marwan A., Basmah H. Alfageh, and Omar A. Almohammed. 2024. "Privacy in Community Pharmacies in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 12, no. 17: 1740. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171740

APA StyleAlrasheed, M. A., Alfageh, B. H., & Almohammed, O. A. (2024). Privacy in Community Pharmacies in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 12(17), 1740. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12171740