Depression Accompanied by Hopelessness Is Associated with More Negative Future Thinking

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.3. Procedure

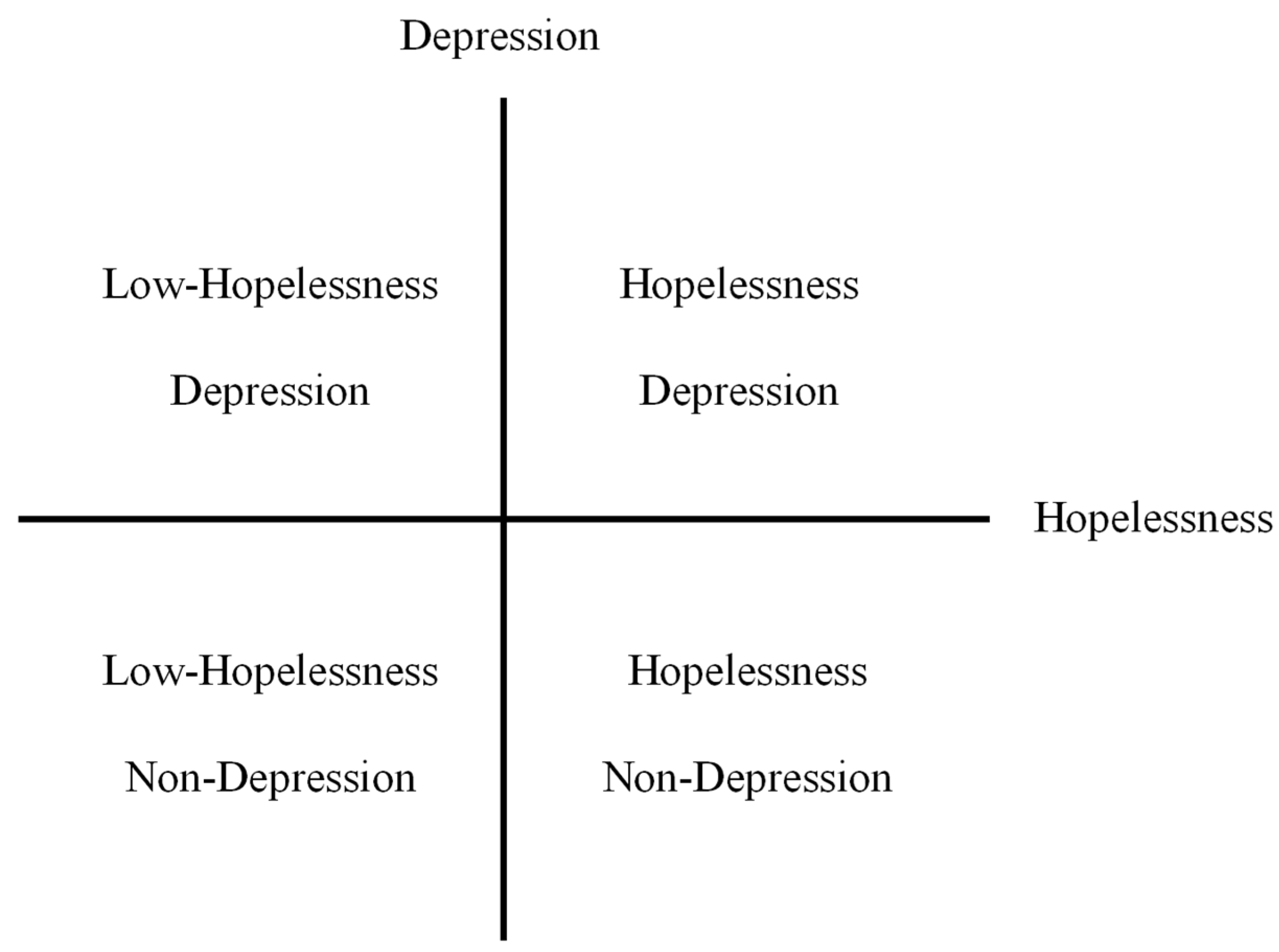

2.4. Groups

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Self-Report Scale Data

3.2. Group Differences in EFT between Depression and Non-Depression

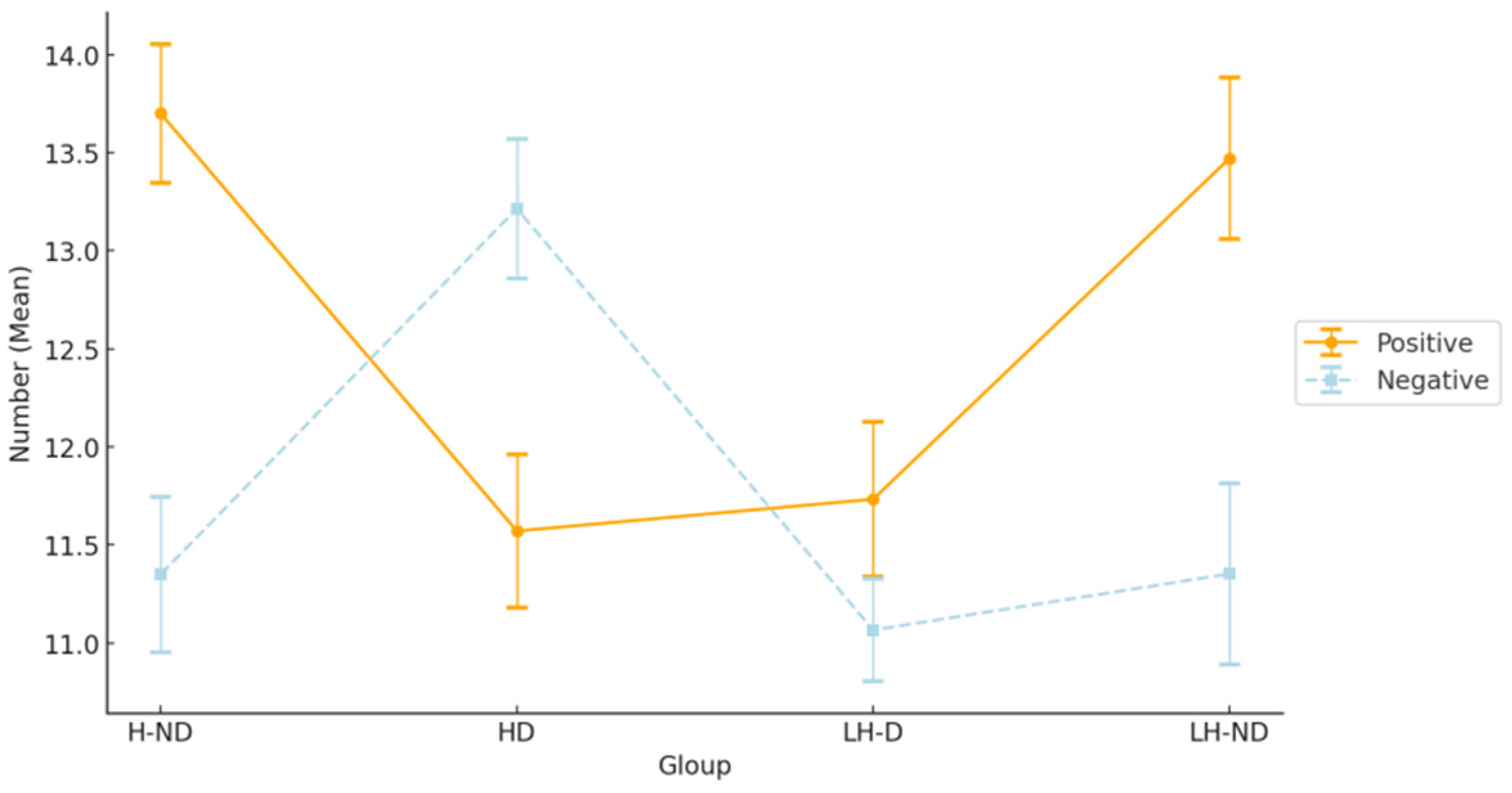

3.3. Group Differences in EFT between the Four Groups

4. Discussion

Limitation and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beck, A.T.; Rush, A.J.; Shaw, B.F.; Emery, G. Cognitive Therapy of Depression; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson, L.Y.; Metalsky, G.I.; Alloy, L.B. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychol. Rev. 1989, 96, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, A.K.; Byrne, A. Anxiety, depression, and the anticipation of future positive and negative experiences. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1996, 105, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atance, C.M.; O’Neill, D.K. Episodic future thinking. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2001, 5, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallford, D.J.; Barry, T.J.; Austin, D.W.; Raes, F.; Takano, K.; Klein, B. Impairments in episodic future thinking for positive events and anticipatory pleasure in major depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 260, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallford, D.J.; Sharma, M.K.; Austin, D.W. Increasing anticipatory pleasure in major depression through enhancing episodic future thinking: A randomized single-case series trial. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2020, 42, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, N.; Nakagawa, A.; Umeda, S.; Terasawa, Y.; Kurata, C.; Tabuchi, H.; Kikuchi, T.; Mimura, M. Frontopolar cortex activation associated with pessimistic future-thinking in adults with major depressive disorder. NeuroImage Clin. 2019, 23, 101877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavender, A.; Watkins, E. Rumination and future thinking in depression. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 43, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLeod, A.K.; Tata, P.; Tyrer, P.; Schmidt, U.; Davidson, K.; Thompson, S. Hopelessness and positive and negative future thinking in parasuicide. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLeod, A.K.; Rose, G.S.; Williams, J.M.G. Components of hopelessness about the future in parasuicide. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1993, 17, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjärehed, J.; Sarkohi, A.; Andersson, G. Less positive or more negative? Future-directed thinking in mild to moderate depression. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2010, 39, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, A.K.; Pankhania, B.; Lee, M.; Mitchell, D. Brief communication Parasuicide, depression and the anticipation of positive and negative future experiences. Psychol. Med. 1997, 27, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLeod, A.K.; Tata, P.; Kentish, J.; Carroll, F.; Hunter, E. Anxiety, depression, and explanation-based pessimism for future positive and negative events. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. Int. J. Theory Pract. 1997, 4, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, A.K.; Salaminiou, E. Reduced positive future-thinking in depression: Cognitive and affective factors. Cogn. Emot. 2001, 15, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallford, D.J.; Austin, D.W.; Takano, K.; Raes, F. Psychopathology and episodic future thinking: A systematic review and meta-analysis of specificity and episodic detail. Behav. Res. Ther. 2018, 102, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosnes, L.; Whelan, R.; O’Donovan, A.; McHugh, L.A. Implicit measurement of positive and negative future thinking as a predictor of depressive symptoms and hopelessness. Conscious. Cogn. 2013, 22, 898–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Haththotuwa, R.; Kwok, C.S.; Babu, A.; Kotronias, R.A.; Rushton, C.; Zaman, A.; Fryer, A.A.; Kadam, U.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; et al. Preeclampsia and future cardiovascular health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2017, 10, e003497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, C.; Vozarova, P.; Sabharwal, A.; Shah, P.; Button, K. Is depression associated with reduced optimistic belief updating? R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 190814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conaghan, S.; Davidson, K.M. Hopelessness and the anticipation of positive and negative future experiences in older parasuicidal adults. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 41, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, R.; O’Connor, D.; O’Connor, S.; Smallwood, J.; Miles, J. Hopelessness, stress, and perfectionism: The moderating effects of future thinking. Cogn. Emot. 2004, 18, 1099–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.T.; Kleiman, E.M.; Nestor, B.A.; Cheek, S.M. The hopelessness theory of depression: A quarter-century in review. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2015, 22, 345. [Google Scholar]

- Starkstein, S.E.; Merello, M.; Jorge, R.; Brockman, S.; Bruce, D.; Petracca, G.; Robinson, R.G. A validation study of depressive syndromes in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2008, 23, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uher, R.; Payne, J.L.; Pavlova, B.; Perlis, R.H. Major depressive disorder in DSM-5: Implications for clinical practice and research of changes from DSM-IV. Depress. Anxiety 2014, 31, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner, T.E., Jr.; Steer, R.A.; Abramson, L.Y.; Alloy, L.B.; Metalsky, G.I.; Schmidt, N.B. Hopelessness depression as a distinct dimension of depressive symptoms among clinical and non-clinical samples. Behav. Res. Ther. 2001, 39, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addis, D.R.; Wong, A.T.; Schacter, D.L. Remembering the past and imagining the future: Common and distinct neural substrates during event construction and elaboration. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 1363–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arie, M.; Apter, A.; Orbach, I.; Yefet, Y.; Zalzman, G. Autobiographical memory, interpersonal problem solving, and suicidal behavior in adolescent inpatients. Compr. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.M.; Broadbent, K. Autobiographical memory in suicide attempters. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1986, 95, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, H.; Kato, M.; Kashima, H.; Asai, M.; Hosaki, H. Effects of disinhibition on performance of the Word Fluency Test in patients with frontal lesions. High. Brain Funct. Res. 1992, 12, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ito, E.; Nagahara, N.; Kanari, A.; Iwahara, A.; Hatta, T. The verbal fluency tasks in the Japa-nese population. In Contemporary Issues of Brain, Communication and Education in Psychology: The Science of Mind; Union Press: Osaka, Japan, 2008; p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, E.; Sakamoto, S.; Ono, Y.; Fujihara, S.; Kitamura, T. Hopelessness in a community population: Factorial structure and psychosocial correlates. J. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 138, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Weissman, A.; Lester, D.; Trexler, L. The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1974, 42, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, M.; Furukawa, T.A.; Takahashi, H.; Kawai, M.; Nagaya, T.; Tokudome, S. Cross-cultural validation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in Japan. Psychiatry Res. 2002, 110, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G. Beck Depression, Inventory—II. Psychological Assessment; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, E.; Sakamoto, S.; Ono, Y.; Fujihara, S.; Kitamura, T. Hopelessness in a community population in Japan. J. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 52, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, A.K. Prospective cognitions. In Handbook of Cognition and Emotion; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Iacoviello, B.M.; Alloy, L.B.; Abramson, L.Y.; Choi, J.Y.; Morgan, J.E. Patterns of symptom onset and remission in episodes of hopelessness depression. Depress. Anxiety 2013, 30, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ribeiro, J.; Huang, X.; Fox, K.; Franklin, J. Depression and hopelessness as risk factors for suicide ideation, attempts and death: Meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 212, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilhauer, J.S.; Cortes, J.; Moali, N.; Chung, S.; Mirocha, J.; Ishak, W.W. Improving quality of life for patients with major depressive disorder by increasing hope and positive expectations with future directed therapy (FDT). Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 10, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Vilhauer, J.S.; Young, S.; Kealoha, C.; Borrmann, J.; IsHak, W.W.; Rapaport, M.H.; Hartoonian, N.; Mirocha, J. Treating major depression by creating positive expectations for the future: A pilot study for the effectiveness of future-directed therapy (FDT) on symptom severity and quality of life. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2012, 18, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | HD (n = 14) | LH-D (n = 15) | H-ND (n = 20) | LH-ND (n = 17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), mean (SD) | 19.7 (0.8) | 20.1 (1.2) | 19.8 (1.4) | 20.2 (1.6) |

| range | 18–23 | 19–21 | 18–23 | 19–23 |

| Gender, n (%) male | 8 (57.1) | 6 (40.0) | 9 (45.0) | 9 (53.0) |

| Verbal fluency total score, mean (SD) | 70.9 (8.6) | 66.4 (7.8) | 64.6 (7.6) | 63.8 (7.7) |

| BDI-II score, mean (SD) | 19.5 (4.4) | 17.1 (2.8) | 10.0 (3.1) | 7.4 (3.1) |

| BHS score, mean (SD) | 11.8 (1.7) | 7.6 (1.4) | 8.2 (0.9) | 5.4 (0.7) |

| Comparison | Adjusted p-Value |

|---|---|

| Positive | |

| H-ND vs. HD | 0.007 |

| H-ND vs. LH-D | 0.011 |

| LH-ND vs. HD | 0.019 |

| LH-ND vs. LH-D | 0.025 |

| Negative | |

| H-ND vs. HD | 0.021 |

| LH-ND vs. HD | 0.023 |

| HD vs. LH-D | 0.012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, H.; Midorikawa, A. Depression Accompanied by Hopelessness Is Associated with More Negative Future Thinking. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121208

Han H, Midorikawa A. Depression Accompanied by Hopelessness Is Associated with More Negative Future Thinking. Healthcare. 2024; 12(12):1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121208

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Hailong, and Akira Midorikawa. 2024. "Depression Accompanied by Hopelessness Is Associated with More Negative Future Thinking" Healthcare 12, no. 12: 1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121208

APA StyleHan, H., & Midorikawa, A. (2024). Depression Accompanied by Hopelessness Is Associated with More Negative Future Thinking. Healthcare, 12(12), 1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121208