Abstract

Family caregivers take on a variety of tasks when caring for relatives in need of care. Depending on the situation and the intensity of care, they may experience multidimensional burdens, such as physical, psychological, social, or financial stress. The aim of the present study was to identify and appraise self-assessment instruments (SAIs) that capture the dimensions of family caregivers’ burdens and that support family caregivers in easily identifying their caregiving role, activities, burden, and needs. We performed an integrative review with a broad-based strategy. A literature search was conducted on PubMed, Google Scholar, Google, and mobile app stores in March 2020. After screening the records based on the eligibility criteria, we appraised the tools we found for their usefulness for family care and nursing practice. From a total of 2654 hits, 45 suitable SAIs from 274 records were identified and analyzed in this way. Finally, nine SAIs were identified and analyzed in detail based on further criteria such as their psychometric properties, advantages, and disadvantages. They are presented in multi-page vignettes with additional information for healthcare professionals. These SAIs have proven useful in assessing the dimensions of caregiver burden and can be recommended for application in family care and nursing practice.

1. Background

Taking on the important role of an informal caregiver is associated with considerable personal demands and a great social impact on the family caregivers of older people and, in the future, on national health and care systems [1]. Against the background of the challenges of a rapidly aging population in Switzerland and internationally, supporting and reducing the burden of family caregivers is of great importance [2,3].

Across the world, the number of older people (60+) is expected to have more than tripled by 2100, increasing from 901 million people in 2015 to 2.1 billion in 2050 and 3.2 billion in 2100 [4]. This means that the number of people in need of care will also increase. Informal care is a necessity for the care of the elderly in most countries and is even a cornerstone of long-term care systems in the region designated by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), comprising 56 countries. Societies rely to varying degrees on the unpaid work of informal caregivers [5,6]. At the same time, the pool of family caregivers is likely to decrease, as the share of the working-age population in countries that are members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is expected to shrink from 67% in 2010 to 58% by 2050. The average contribution of family caregivers varies significantly between countries depending on the definition and measurement modality [7]. In the EU, for example, family caregivers, mainly women, provide over 80% of all care [8].

We define family caregivers as persons who care for, look after, and, if necessary, assist a close relative who is ill and/or in need of care with personal hygiene and activities of daily living [9]. We use the term family to refer to closely related individuals and informal caregivers, regardless of family relationship [10]. Role theory provides additional guidance, explaining that family caregivers behave in different, predictable ways depending on their respective social identities (spouse, child, etc.) and the situation [11]. Self-assessment instruments (SAIs) may assess such aspects of caregiving. Deeken et al. have conducted a comprehensive literature review of SAIs to identify and critically appraise such instruments developed for research purposes [1]. This is in line with the policy agenda in Europe, which is to build knowledge bases in order to systematically generate measures supporting informal care [12].

Self-assessment, defined here as the process of exploring and evaluating oneself and aspects of caregiving, is important because it can enable self-awareness of the impact of family caregiving tasks. The tasks that family caregivers perform can be perceived as stressful and burdensome but can also have positive effects, such as personal growth. From a family system perspective, informal caregiving enables a deeper connection between the person being cared for, the family caregiver, and the broader family system, as well as the development of resilience and intimacy. On the other hand, caregiving has an impact on all that are involved, for example by disrupting home life and juggling competing roles [13]. The caregiver’s role is multifaceted and may be financial, administrative, and/or coordinative. Family caregivers also provide help with daily activities and household chores, as well as emotional and social support [9,14]. The degree of burden varies depending on the situation. Findings suggest that the amount of time spent and the intensity of care are key indicators of the experience of burden caused by caregiving tasks [9] (p. 43ff).

In addition to these indicators, the clinical picture of the relative in need of care is among the so-called objective stressors, which form the basis of stress models [15,16]. In Pearlin’s stress model [16,17], which guides our work, family caregivers’ stress can be viewed as the result of a process involving several interrelated conditions, including the socio-economic characteristics and resources of family caregivers and the primary and secondary stressors to which they are exposed. Primary stressors are hardships and problems that are directly rooted in caregiving. Secondary stressors are (1) the stresses experienced in roles and activities independent of caregiving activities and (2) intrapsychic stresses that negatively affect the self-concept. Consequently, the subjective experience of stress may differ for the same objective stress parameters (e.g., socio-economic characteristics), as the subjective evaluation of a stressful situation also depends on individual secondary stressors.

Various dimensions of family caregivers’ burden that influence each other or are mutually dependent have been identified [9,14,18]. According to Otto et al. [9], these include, for example, being under time pressure and having little time and energy for themselves, psychological burdens such as stress, depression, excessive demands, or burnout, physical burdens such as pain from heavy lifting, social burdens due to family and/or role conflicts, loneliness, and social isolation, or financial burdens. Bastawrous [19] discusses the concept of “caregiver burden” and concludes that the multiple definitions of “caregiver burden” lead to vague findings that are difficult to summarize and appraise in a consistent manner. At the same time, the applicability of these findings in clinical and policy settings is limited. We followed Bastawrous’ [19] recommendation to use stress theory and role theory as guiding frameworks to capture the contextual features of caregiver burden that are relevant to caregiving outcomes. In doing so, we used Pearlin’s stress model to guide our work [16,17]. Moreover, by focusing on SAIs to highlight the unique experiences of each informal caregiver, we used role theory to facilitate our understanding of how “caregiver burden” can arise as a result of role conflict and role overload [11]. Thus, we defined “caregiver burden” broadly to capture its multidimensional aspects, such as burden, strain, insufficient coping, stress, and insufficient caregiver mastery.

Coping strategies and social support by healthcare professionals (HCPs) can potentially address several points in the stress process. Therefore, understanding the nature of burden, measuring caregivers’ strain, and integrating this information into family care practice is crucial to effectively support family caregivers. To implement a family system focus, we need to use a systemic approach that aims at sustainably improving the everyday care management of families and enabling them to live their daily lives together in the home setting [20,21]. The aim is, therefore, to prevent family members from becoming overburdened and running the risk of falling ill themselves. To achieve this, a partnership is sought between the person being cared for, the family caregivers, and professionals [22].

In order to be able to offer, develop, and evaluate adequate services and support for family caregivers, it is essential to appropriately assess the situation of family caregivers in the home environment as a first step. SAIs can be used for this purpose. That is, SAIs support family caregivers in easily identifying their caregiving role, activities, burden, and needs. Therefore, the following research questions guided this study: (1) Which SAIs capture the dimensions of family caregivers’ burden? (2) Which SAIs can be recommended for designated use by family caregivers and to inform nursing support in family practice? Accordingly, the aims of this study are to identify SAIs, examine their purpose and key characteristics, and appraise SAIs that can successfully be applied in family care and nursing practice. We also aimed at developing instrument vignettes in order to generate guidance for HCPs.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

To address the first research question, we conducted an integrative review to find suitable instruments. We based our approach on Whittemore and Knafl’s [23] integrative review, which aims to include empirical and theoretical literature to create a comprehensive understanding of the topic [24].

An integrative review offers a unique advantage for identifying and evaluating SAIs for family caregivers by integrating and synthesizing both studies with different methodologies (experimental, non-experimental, qualitative, quantitative) and instruments used in family and nursing practice, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness of tools in real-world caregiving scenarios. This is consistent with the emphasis on integrative reviews in nursing science due to their highlighting multiple perspectives [25]. Addressing methodological complexity is crucial. While methods of data collection and extraction have been developed, robust methods of analysis and synthesis specific to integrative reviews are still being developed [26]. This is particularly important when dealing with the large and diverse data sets, which are common in integrative reviews. Our study aims to contribute to this ongoing development by critically discussing the methods used.

To answer the second research question, we appraised the instruments found in the references using predefined evaluation criteria, to identify instruments that can successfully and usefully be applied in family care and nursing practice.

2.2. Search Strategy

This integrative review followed a broad strategy and was divided into three strings: (1) a systematic search in the PubMed database, (2) a hand search in Google Scholar, Google, reference screening in literature reviews, in German-language journals, and in different app stores, and (3) contacting selected institutions, organizations, and experts in the field of supporting burdened family caregivers to identify additional relevant published and unpublished research.

In strings 1 and 2, we used a multi-phase search process to first identify potentially relevant instruments in the literature. In string 3, we received information on the instruments used. We then searched for published reports on measures that had been assessed for their suitability.

This comprehensive search strategy without time limits aimed to find instruments published in English, German, French, and Italian. The literature search took place in March 2020. The work of Deeken et al. [1] and the FOPH [2] served as the basis for the development and selection of the search terms, which were combined into search strings. The detailed search strategy can be found in Supplementary File S1. The following key terms were used and adapted to the different databases: patient reported outcome measure OR self-report OR questionnaire AND needs assessment OR stress OR burden OR exhaustion AND caregiver OR family AND community health service OR home care service. We used MeSH terms and PubMed as the only database to streamline the search process, and we accepted that we might miss relevant studies using alternative terminology. We compensated for this with the hand search.

The systematic search in PubMed (1) was performed with English-language search terms. The hand search (2) was conducted in Google Scholar (English, German) and Google (German, French, Italian). Since Google search engines cannot be searched systematically, different combinations of search terms were used and the first 100 hits of each search run were screened [27]. Both the systematic search and the hand search were conducted independently by four people. To identify instruments that are used in family care and nursing practice, (3) selected organizations, institutions, and experts were also contacted via email. The people contacted were asked to report the self-assessment tools they used.

2.3. Record and Instrument Screening

The literature selection and data extraction were carried out in a three-step process, based on the method described by Kleibel and Mayer [28]: (1) title and abstract screening against the inclusion and exclusion criteria in Table 1, (2) review of full texts against the eligibility criteria, and (3) review of instruments in the remaining full texts against the eligibility criteria and screening the instruments. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1. No restrictions of a methodological nature (e.g., only psychometrically tested instruments) were placed. All types of SAIs were included to allow for the inclusion of self-developed instruments and applications in app stores in addition to scientifically developed instruments [1]. SAIs developed exclusively for use in nursing homes were excluded, as the focus is on the home care situation of family caregivers. However, SAIs developed and used in the hospital setting were included as they can also be used by family caregivers in the home setting. SAIs were excluded if any of the content item exclusion criteria were met.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for full text analysis and eligible instruments.

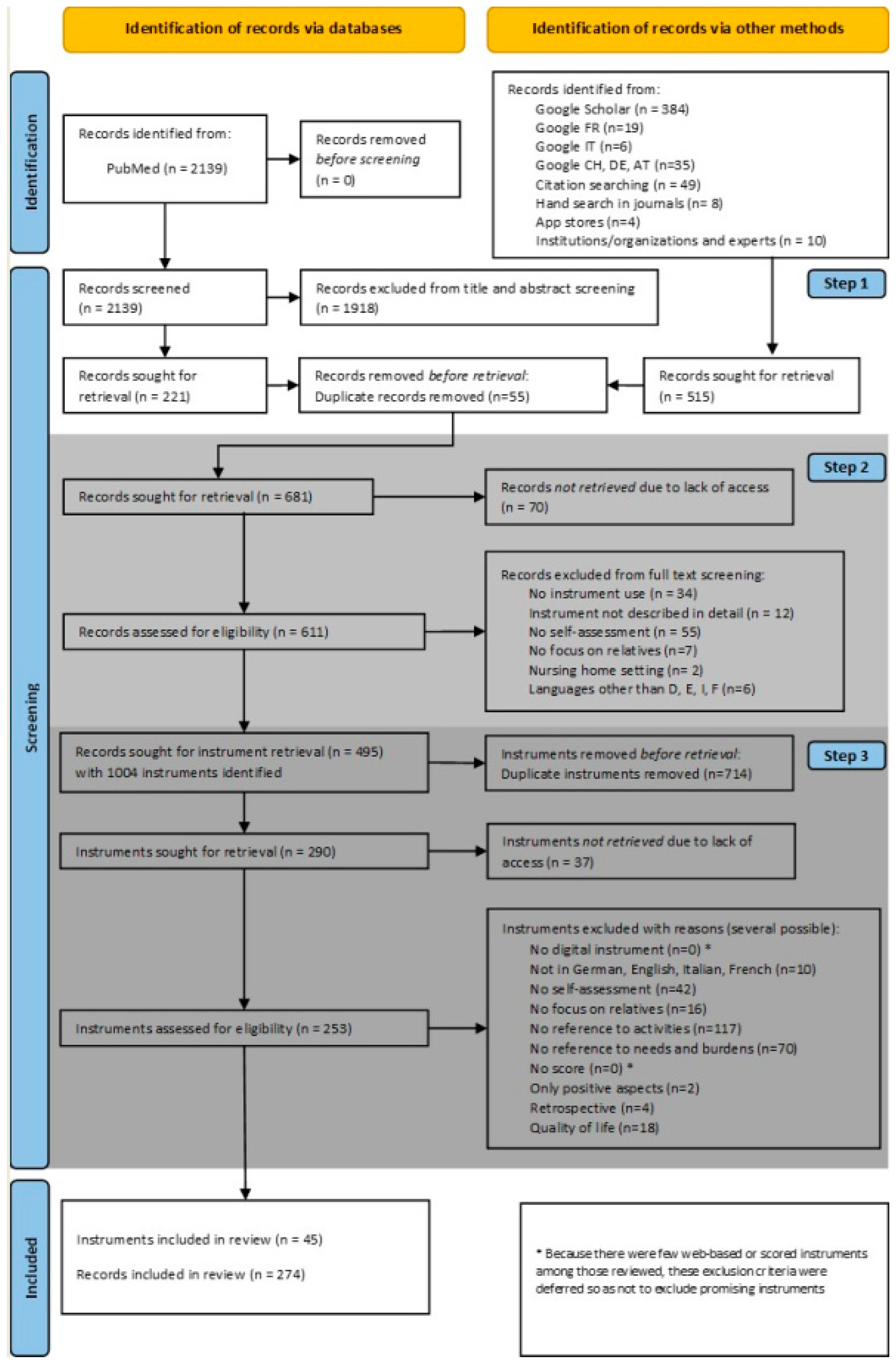

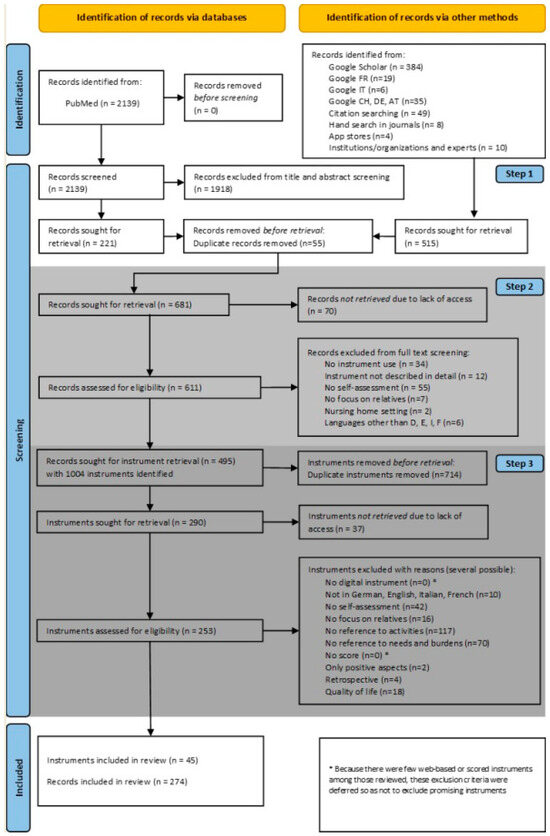

In the selection process, we use the term record because the individual hits in the search process include studies, grey literature, instruments per se, and apps. A flowchart of the literature search is shown in Figure 1 and illustrates the following three steps of the screening process, based on Kleibel and Mayer [28]. First, (1) records from the systematic search in PubMed were imported into a reference management system and independently screened by title and abstract by two people. Records that did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria were excluded. Afterwards, the records found in the systematic search and potentially matching records from the hand search were combined and duplicates were removed. In the second step, (2) the remaining records were imported into Excel and the corresponding full texts (if applicable) were retrieved. We extracted the following information for each record: author(s), title, year of publication, name of the instrument, abbreviation (if available). If a record included multiple instruments, multiple rows were created. The reasons for exclusion were noted in one column. Thirdly, (3) the instruments themselves were extracted, unless the instrument was already exclusively available, and checked again separately against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by two researchers. Discrepancies were discussed with a third researcher. For this step, we listed the instruments alphabetically and erased duplicates. We extracted, again in Excel, the following information for each instrument: name of the instrument, abbreviation (if available), developer, continent, target group, aim/purpose, and content elements. The reasons for exclusion were noted in one column. During this step, it became clear that there are few web-based instruments and not all of them have a score. It was therefore decided to discard the predefined inclusion criteria of instrument type in order not to exclude a priori any potentially important instruments that could potentially be converted into web-based forms in the future or that have the potential to stimulate reflection on the situation of family caregivers. Whittemore and Knafl [23] identify the following steps in their discussion of data analysis: data reduction, data display, and data comparison. In terms of the three steps described above, steps 1 and 2 were data reduction, data display comprised steps 2 and 3, while data comparison occurred in step 3.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the literature search.

2.4. Appraisal for Applicability in Family Care and Nursing Practice

After the extraction of SAIs according to the inclusion criteria, an evaluation against the predefined content elements was conducted to identify and appraise useful instruments that can successfully be applied in family caregiving and nursing practice. This evaluation followed guideline No. 6 for “family caregivers of adults” [29] from the German Society of General Practice and Family Medicine (DEGAM). The DEGAM develops scientifically sound and practice-proven guidelines according to the principles of evidence-based medicine.

SAIs were assessed using evaluation criteria that included the following content components, based on the work of Pearlin et al. and Otto et al. [9,16]: (1) referral to activities/tasks as a family caregiver; (2) intensity of caregiving activities; (3) caregiver burden and positive impact of the caregiving situation; (4) caregiver support needs; (5) caregiver health status; (6) psychometric properties such as the use of a rating scale, summative outcome, and/or cut-off score.

Since the focus was on SAIs, the studies or records from which the instruments were extracted were not subjected to a quality appraisal. Accordingly, no assessment was made of the descriptions of the SAIs there. Instead, the quality appraisal of SAIs was based on the content evaluation criteria. We selected SAIs which included content components (1), (2), and (3), were able to assess primary and secondary stressors, and (6) allowed for the quantification of self-assessed caregiving tasks as well as of the subjective burden and positive effects of caregiving. If SAIs met all 4 criteria, they were deemed very suitable for application in family caregiving and nursing practice.

After appraising and selecting SAIs suitable for family caregiving and nursing practice in that way, we analyzed them in depth against the following criteria: psychometric properties such as number of items, rating scale/sum score, cut-off score, and validation of the respective SAI; conclusion on the applicability of the SAI in family care and nursing practice; as well as advantages and disadvantages. To generate guidance for HCPs, instrument vignettes were developed for instruments that were analyzed in depth. To develop the instrument vignettes, we consulted additional literature in order to be able to give a comprehensive picture of the respective instruments. Each multi-page vignette comprises a part giving an overview of the SAI and a part providing more in-depth information (see Supplementary File S3).

3. Results

A total of 2654 publications were identified based on a systematic literature search of the PubMed database, a hand search, and from the contacts made with institutions, organizations, and experts. The systematic search in PubMed yielded n = 2139 potential instruments via publications, the hand search n = 5, and contacting institutions, organizations, and experts yielded n = 10. A total of 681 full texts were reviewed against the eligibility criteria. From the remainder of n = 495 publications, n = 1004 instruments were identified. After removing duplicates and screening the instruments for eligibility, n = 45 instruments from a total of n = 274 records could finally be included. The flowchart of the literature search is shown in Figure 1.

3.1. Results: Instruments for Assessing Burden in Family Caregivers

Our integrative and systematic search resulted in 45 instruments that fulfilled the eligibility criteria. The following information relates to the contents listed in Table 2, which provides an overview of the characteristics of each included instrument. The instruments included are from 274 records listed in Supplementary File S2.

Table 2.

Overview of the included instruments (n = 45).

To answer our first research question, we identified 45 instruments that capture the dimensions of the family caregiver burden associated with caregiving tasks and their intensity. These instruments were mainly developed in North America (n = 26) and in Europe (n = 16), followed by Asia (n = 5) and Australia (n = 1).

Regarding the target group, the majority of the instruments focus on adult family caregivers regardless of their age (n = 32) and one instrument each addresses caregiving parents of sick children and caregiving spouses. Another seven instruments refer to caregivers without any age specification and only four instruments are explicitly suitable for older caregivers aged 50 and older. Instruments specifically target family caregivers of older adults (n = 10), individuals with neurological conditions including dementia or Alzheimer’s disease (n = 14), cancer (n = 5), psychiatric (n = 4), palliative (n = 3) cardiac (n = 1), or hematologic conditions (n = 1). Only one instrument targeted family caregivers of children (n = 1). Eight instruments are without specification.

The instruments include items about the negative (such as burden, strain, stress) and/or positive (such as personal growth) effects of family caregiving. All forty-five instruments address negative effects, and three instruments (Nr. 16: Caregiver Tasks Inventory; Nr 25: Carers of Older People in Europe—COPE Index; Nr. 31 Hemophilia Caregiver Impact measure) address both. They also focus on different dimensions of burden. Some assess objective burdens such as caregiving tasks or intensity of care, and others focus on subjective burdens such as stress and other conditions resulting from caregiving.

Forty-one instruments had a score. Because we included instruments regardless of their psychometric properties, it is important to keep in mind that the presence of a score is not equated with good psychometric properties. Thirty instruments were related to the tasks that family caregivers perform. At least 15 instruments referred to the health status of the family caregiver and 15 instruments included the intensity of care or support effort; only 13 referred to needs or support needs. Some of the instruments included were developed for professional or scientific use.

Among the instruments included is the Carers Assessment of Difficulties Index (CADI). This instrument was not found to be useful for practice. However, in combination with the Carers Assessment of Satisfactions Index (CASI) and the Caregiver Assessment Management Index (CAMI), it would meet the inclusion criteria as a combination of tools that is comprehensive but may help to clarify complexity. Because we were looking for single tools, we did not include the CASI-CADI-CAMI combination. Similarly, both the Multidimensional Assessment of Caring Activities (MACA) and the Positive and Negative Outcomes of Caring (PANOC) [77] were excluded as each of them did not fulfill the eligibility criteria. MACA focuses on tasks but is not related to burdens, while PANOC focuses on caring outcomes. If one follows the recommendation to use MACA and PANOC combined, burdens and positive outcomes are considered. Still, these instruments are intended for professional or scientific use. We were looking for instruments that are easy to understand and suitable as SAIs. The MACA and PANOC are easy to understand but must be used with guidance from a professional.

3.2. Results: Applicability in Family Care and Nursing Practice

To answer the second research question, the included n = 45 SAIs were first analyzed in terms of their content components. Nine SAIs were judged to be particularly suitable for use in family caregiving practice as they included the content components we selected as our evaluation criteria: (1) caregiving tasks, (2) intensity of caregiving activities, (3) caregiver burden and/or positive effects of the caregiving situation, and (6) psychometric properties such as sum score, rating scale, or cut-off score. Table 3 describes the output of the in-depth analyses of these nine SAIs. They are listed in alphabetical order according to instrument name (abbreviation in parentheses); the authors and the respective publications are mentioned.

Table 3.

Most suitable SAIs (n = 9) for application in family care and nursing practice.

As seen in Table 2, all included instruments (n = 45) focus on different dimensions of burden. Some assess objective burdens, such as the time spent on caregiving tasks and their intensity; others focus on subjective burdens such as psychological stress and other conditions resulting from caregiving.

The following SAIs can be used to measure mainly psychological stress (≥ 50% of the items): the Caregiver Self Assessment Questionnaire—CSAQ; the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers—BSFC; the Caregiving Health Engagement Scale—CHE-s; the Family Caregiver Distress Assessment Tool; and the Caregiving Appraisal Scale—CAS. The following SAIs can be used to measure psychological stress (< 50% of the items) as well as physical, socio-economic, and/or temporal stress: the Zarit Burden Interview—ZBI; the Caregiver Strain Index—CSI; and the Caregiver Burden Inventory—CBI. The psychometric properties, such as number of items, rating scale/sum score, and cut-off score, of the respective SAIs are shown in Table 3. As far as validation is concerned, seven out of the nine SAIs have been validated, mainly in English. The Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) has been most frequently translated, culturally adapted, and validated in several languages.

To sum up, these instruments (n = 5) are short and easy-to-understand questionnaires that can be used independently by family caregivers. At the same time, they all have a high level of acceptance. All instruments have the potential to depict family caregiving as a multidimensional process that takes into account the time and the developmental, physical, social, and emotional issues of family caregivers.

In conclusion, aspects of the applicability of these SAIs in family care and nursing practice as well as their advantages and disadvantages are shortly described in Table 3; detailed instrument vignettes can be found in Supplementary File S3. No digital web-based application, which would further facilitate assessment and outcomes through automation, is available among the instruments (n = 7). All instruments more or less explicitly recommend that their application be supported by nursing or social work professionals (or other healthcare professionals) to interpret the self-assessment results and plan appropriate support measures.

4. Discussion

The aims of the present integrative review were to identify SAIs that capture content elements such as the burden of family caregivers, appraise the suitable instruments, develop instrument vignettes in order to generate guidance for HCPs, and verify the applicability of SAIs for family caregivers and nursing practice.

Our practical contribution is an evidence-based, systematic approach to searching, screening, and evaluating the identified SAIs for their use in family caregiving and nursing practice. We have presented each of the nine final SAIs in a multi-page vignette that provides professionals with an immediate, condensed overview of each SAI (Supplementary File S3). Our theoretical contribution is a discussion of the integrative review method.

Kirkevold [25] argued that integrative nursing research can improve the development of nursing science and make research-based knowledge more accessible to clinical nurses. In particular, integrative reviews have become increasingly popular in the field of nursing. Hopia et al. [82] saw the potential of integrative reviews for the nursing field, but at the same time emphasized a systematic approach.

For Elsbach and van Knippenberg [83], the benefit of the integrative review is that it goes beyond a mere summary of the literature and adds something new through critical analysis. Integrative reviews can both consolidate evidence and generate new ideas to advance a field of study. They further argue that insights should arise from the integrative review rather than guide it. In this context, they advocate a more open approach. This can of course be seen as a contradiction to the required systematic approach. Alvesson and Sandberg [84] critique conventional views of integrative reviews and propose an alternative approach called a problematizing review, which emphasizes reflexivity, selective reading, problematizing the existing literature, and the concept of “less is more”. The problematizing review is seen as an “opening exercise” that generates new and better ways of thinking about particular phenomena or issues. Given this, we will discuss the practical contribution made by this review.

After a sensitive literature search, a total of 45 SAIs were identified. Nine contained all the content elements we deemed important for practical application to family care and nursing practice. The authors of these instruments describe the assessment of the extent of burden as the main purpose of the respective self-assessments, and it is assumed that all nine instruments are suitable for analyzing the extent of perceived burden. The demand to develop a corresponding digital, web-based instrument is strengthened by the results.

Thus, SAIs can help in the systematic identification of strengths and socio-economic, physical, and psychological risks in order to suggest tailored support and to initiate a personality development process. The results of qualitative studies indicate that the positive aspects of informal caregiving are also related to personal growth [85,86]. This includes the feeling of competence and accomplishment of difficult tasks. The sense of accomplishment also relates to skills and relationships, for example, having a closer relationship with and being able to give back to the person being cared for as well as discovering inner strengths through connecting with others. Feeling gratitude can also be a positive aspect of caregiving [85,86]. HCPs can support caregivers in identifying the positive aspects of caring and developing their personal strengths.

Concerning negative aspects, caregivers identify physical and emotional stress as well as feeling unprepared or unsupported as central challenges [86]. In their systematic review, Bom et al. [87] conclude that the included studies indicate a causal negative impact of caregiving on physical and mental health. The subgroup of married female caregivers, in particular, appears to experience negative health effects of caregiving [87]. Consultations with HCPs play a critical role in collaborative reflection and in the selection of an appropriate intervention. For example, an individual family caregiver’s burden profile may be the outcome of the application of an SAI that can be discussed during a consultation with a HCP, as early as possible, and that can give the HCP a chance to verify whether and how their interventions have had an impact on the family caregiver’s situation [79].

For family caregivers, self-assessment has been found to be useful for self-reflection and self-awareness and provides a basis for discussion with professionals. A study in a palliative care unit reported very positive experiences [88]. According to the study, the SAI used provided direction, focus, and structure for discussion with professional caregivers and identified the needs of family caregivers.

The results of a meta-analysis by Sörensen et al. [89] demonstrated a potential for the improvement of caregiver burden. However, spousal caregivers benefited less than adult children. Individually tailored interventions have been shown to be more effective at improving caregiver well-being. A systematic review by Lopez-Hartmann et al. [90] shows that the effects of caregiver support interventions are small and inconsistent between studies. They propose interventions tailored to the caregivers’ individual needs. Technology-based interventions can have a positive effect on caregiver self-efficacy, self-esteem, and burden [91]. In a rapid review of systematic reviews, Spiers et al. [92] concluded that the current evidence fails to determine how caregivers should be supported and that further studies are needed to identify appropriate interventions. We suggest that HCPs should focus on vulnerable subgroups, such as married female caregivers, and use SAIs as tools to support the reflection process and identify individually tailored interventions. SAIs are also becoming increasingly important in scientific discourse and exist for different diseases and settings. From an interprofessional perspective, family caregivers, home care professionals, and general practitioners experience psychological burden as the most serious form of burden. General practitioners and nurses cited a lack of interprofessional education, lack of time, and lack of compensation as the main problems. Family caregivers valued communication with primary care physicians and nurses [93]. Empowering family caregivers to use SAIs may be one way to address this gap in care.

It should be noted that many of the instruments found that looked promising at first sight often had gaps, and thus may require a combination of instruments for the respective area of application. The methodological approach of the present study was deliberately integrative in order to identify instruments used both in research and in practice. Accordingly, app stores were also searched. None of the identified apps were analyzed in more detail, not because they were not user-friendly, but because essential content aspects were missing. In general, it should be noted that there are few web-based or digitally available tools. In a review, Firmawati et al. identified mobile applications for family caregivers of people with stroke as supportive [94]. Studies have found evidence that mHealth or eHealth tools for family caregivers have an impact on the burden of care [95].

Over the past 45 years, researchers have developed SAIs to assess family caregivers. Many studies have shown that applying SAIs has an impact on identifying different dimensions of burden [1]. This integrative review has identified valuable and promising instruments that, with translation, cultural adaptation, and web-based support, could be applied in a low-threshold way in order to identify caregiver burdens early and accompany the challenges of care with the support of HCPs. It can be also stated that there is a lack of empirical studies investigating the relationship between regular self-assessment of family caregivers and burden reduction.

Strengths and Limitations

In light of the methodological discussion above, we have opted for a systematic approach. Nevertheless, our formulation of purpose was not quite as specific as Hopia et al. [82] recommend. In addition, we used the integrative review method to find SAIs. This meant that the target of our search were both the instruments themselves and studies through which these instruments were obtained. With this decision, we expanded the classic approach. In order to achieve all our objectives, we divided our approach into several sub-steps, presented our actions in detail, and provided further information on our review in Supplementary Files (S1–S3). Due to our broad strategy, we only included Google Scholar and PubMed as scientific databases. More scientific databases could have been included. In the spirit of reflexivity, we acknowledge that free terms in addition to MeSh terms would have been useful. As the literature search was conducted in 2020, possible new or updated SAIs may not have been taken into account. Since minor changes to the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the context of reviews can mean serious differences in results [24], these should be critically considered by each reader and questioned for their own context of application. One of the strengths of this integrative review is our four-language search strategy. Our broad approach, as well as our constant discussion process in the preparation of the present study, can be seen as strengths. Since literature studies are only as good as the data, specifically the publications included, publication bias cannot be ruled out [24].

5. Conclusions and Implications

In principle, the present work on identifying and evaluating self-assessment instruments can be regarded as an important first step to strengthen theoretical and applied knowledge. The integrative method was used to identify instruments used for research and practice. As for the application of these instruments in practice, the question arises as to how the most appropriate instruments can be made available and accessible to the family caregivers.

SAIs have the potential to increase family caregivers’ self-awareness of their role, the resulting burden, and the need for professional support. There are indications that low-threshold dissemination to family caregivers via care providers or information services is possible [42]. In order to clarify the when, how, and why, it is important to understand the interactions between the national structural order, the institutional forces, their impact on people’s well-being, and people’s physical and mental health and their ability to assert and develop themselves in their social roles (e.g., as family caregivers). To promote understanding and accompany the introduction of self-assessment instruments into practice, it is recommended to consult basic concepts such as stress process models [15,16], dynamic models [96], or caregiver identity theories [97]. Not only general practitioners or family doctors but also community health nurses are in a suitable position to apply the best-fitting instrument. One of the core competences of the community health nurse, for example in Germany, but also in other countries, is the application of assessments in outpatient care [98].

It is obvious that further studies and research efforts are needed in order to be able to determine the specific cut-off values and the resulting effective interventions. It is also central to find out what the uses and acceptance levels of the individual SAIs will be for family caregivers in different settings, on the one hand, and in communities on the other. Especially for professionals who are in contact with family caregivers, multidimensional instruments, such as assessments of subjective and objective stress dimensions, are of particular interest. Our integrative review covers the period up to 2020; an update would be useful for the period after that. Furthermore, the development of digital and web-based instruments is an important implication for settings, countries, or institutions that want to support family caregivers. Furthermore, through this review, the SAIs identified in Supplementary File S3 can be a basis for further intervention development research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare12101016/s1, Supplementary File S1: Database searches; Supplementary File S2: References for included instruments [16,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224,225,226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240,241,242,243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254,255,256,257,258,259,260,261,262,263,264,265,266,267,268,269,270,271,272,273,274,275,276,277,278,279,280,281,282,283,284,285,286,287,288,289,290,291,292,293,294,295,296,297,298,299,300,301,302,303,304,305,306,307,308,309,310,311,312,313,314,315,316,317,318,319,320,321,322,323,324,325,326,327,328,329,330,331,332,333,334,335]; Supplementary File S3: Result vignettes for self-assessment instruments [15,34,36,42,43,46,48,49,54,76,106,107,108,109,113,114,117,121,125,127,129,171,175,182,185,199,201,267,268,269,271,273,287,288,289,295,297,305,308,336,337,338,339,340,341,342,343,344].

Author Contributions

F.D.B. and A.F. conceptualized the literature search; F.D.B. and M.H. performed the literature search as well as the study and instrument selection; F.D.B. analyzed the instruments with critical feedback from M.H. and A.F.; F.D.B. and M.H. drafted the manuscript and A.F. critically revised it. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was conducted on behalf of the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, FOPH. The funding source had no role in writing the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval was not applicable as this was an integrative review) Selected organizations, institutions, and experts were contacted via email and asked to identify instruments that are used in family care and nursing practice. By responding to our inquiry, they contributed to this project. The names of the inquired persons will not be published.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable (integrative review).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) for the trust placed in us to carry out this mandate (2019–2020) to produce a collection of self-assessment instruments for family caregivers, which was the basis for this publication. We would like to thank Eleonore Baum (E.B.), Janine Vetsch (J.V.), and Heidrun Gattinger (H.G.) from Eastern Switzerland University of Applied Sciences OST for contributing to the literature search and for their valuable and supportive collaboration. We also thank Peter Sikl (P.S.) for his contribution to this paper. Peter is an Nursing student at Vinzenz Pallotti University in Vallendar, Germany, who completed his research internship at Zurich University of Applied Sciences in Winterthur, Switzerland, and supported us with the first draft of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

List of Abbreviations

| SAI | Self-assessment instrument |

| HCPs | Healthcare professionals |

All abbreviations of SAIs are in parentheses following the respective instrument.

References

- Deeken, J.F.; Taylor, K.L.; Mangan, P.; Yabroff, K.R.; Ingham, J.M. Care for the caregivers: A review of self-report instruments developed to measure the burden, needs, and quality of life of informal caregivers. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2003, 26, 922–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiss Federal Office of Public Health FOPH. Support for Relatives Providing Care and Nursing; Swiss Federal Office of Public Health FOPH: Berne, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Informal Care in Europe—Exploring Formalisation, Availability and Quality; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations UN. The World Population Prospects: 2015 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNECE. The Challenging Roles of Informal Carers; The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe UNECE: New York, NY, USA; Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Scheil-Adlung, X. Long-Term Care (LTC) Protection for Older Persons: A Review of Coverage Deficits in 46 Countries; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, F.; Llena-Nozal, A.; Mercier, J.; Tjadens, F. Help Wanted?: Providing and Paying for Long-Term Care; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, F.; Rodrigues, R. Informal Carers: Who Takes Care of Them? European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research: Vienna, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, U.; Leu, A.; Bischofberger, I.; Gerlich, R.; Riguzzi, M.; Jans, C.; Golder, L. Bedürfnisse und Bedarf von betreuenden Angehörigen nach Unterstützung und Entlastung—Eine Bevölkerungsbefragung. In Schlussbericht des Forschungsprojekts G01a des Förderprogramms Entlastungsangebote für Betreuende Angehörige 2017–2020; I.A.d.B.f.G., Ed.; Bundesamts für Gesundheit (BAG): Bern, Zürich, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bozett, F. Family Nursing and life-threatening illness. In Families and Life-Threatening Illness; Leahey, M., Wright Mc Clenny, L., Eds.; Nursing Management Springhouse: Springhouse, PA, USA, 1988; Volume 4, p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle, B.J. Recent Developments in Role Theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1986, 12, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, U.; Sundström, G.; Johannson, L.; Tortosa, M.A. Policies to support informal care. In Long-Term Care Reforms in OECD Countries; Gori, C., Fernandez, J.-L., Wittenberg, R., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, C.L.; Mullis, M.D.; Kastrinos, A.; Wollney, E.; Weiss, E.S.; Sae-Hau, M.; Bylund, C.L. “Home wasn’t really home anymore”: Understanding caregivers’ perspectives of the impact of blood cancer caregiving on the family system. Support Care Cancer 2021, 29, 3069–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügger, S.; Rime, S.; Sottas, B. Angehörigenfreundliche Versorgungskoordination. In Schlussbericht des Forschungsprojekts G07 des Förderprogramms Entlastungsangebote für Betreuende Angehörige 2017–2020; I.A.d.B.f.G., Ed.; Bundesamts für Gesundheit (BAG): Bern, Zürich, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis; Free Association Books: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Mullan, J.T.; Semple, S.J.; Skaff, M.M. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 1990, 30, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Schooler, C. The Structure of Coping. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1978, 19, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, H.; Arrer, E.; Berger, F.; Hechinger, M.; Sellig, J.; Stängle, S.; Otto, U.; Fringer, A. Unterstützung für Betreuende Angehörige in Einstiegs-, Krisen- und Notfallsituationen; Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG: Bern, Zürich, 2019; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- Bastawrous, M. Caregiver burden—A critical discussion. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.M. Family Systems Nursing: Re-examined. J. Fam. Nurs. 2009, 15, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.M.; Bell, J.M. Illness Beliefs: The Heart of Healing in Families and Illness, 3rd ed.; 4th Floor Press: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shajani, Z.; Snell, D. Wright & Leahey’s Nurses and Families: A Guide to Family Assessment and Intervention, 7th ed.; F. A. Davis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritschl, V.; Weigl, R.; Stamm, T. Wissenschaftliches Arbeiten und Schreiben. Verstehen, Anwenden, Nutzen für die Praxis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkevold, M. Integrative nursing research—An important strategy to further the development of nursing science and nursing practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 25, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, V.S.; Isaramalai, S.A.; Rath, S.; Jantarakupt, P.; Wadhawan, R.; Dash, Y. Beyond MEDLINE for literature searches. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2003, 35, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhausen, T.; Hirt, J. RefHunter. Manual zur Literaturrecherche in Fachdatenbanken; Version 4.0; Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg: Halle, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kleibel, V.; Mayer, H. Literaturrecherche für Gesundheitsbesuche; Facultas: Vienna, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lichte, T.; Höppner, C.; Mohwinkel, L.-M.; Jäkel, K.; Wilfling, D.; Holle, D.; Vollmar, H.C.; Beyer, M. DEGAM Leitlinie zur Pflegende Angehörige Erwachsener; Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf: Hamburg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Budnick, A.; Kummer, K.; Blüher, S.; Dräger, D. Pflegende Angehörige und Gesundheitsförderung. Pilot. Zur Validität Eines Deutschsprachigen Assess. Zur Erfass. Von Ressourcen Und Risiken Älterer Pfleg. Angehöriger (ARR) Z. Für Gerontol. Und Geriatr. 2012, 45, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glajchen, M.; Kornblith, A.; Homel, P.; Fraidin, L.; Mauskop, A.; Portenoy, R.K. Development of a brief assessment scale for caregivers of the medically ill. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2005, 29, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, S.C.; Gubman, G.D.; Horwitz, A.V.; Minsky, S. Burden assessment scale for families of the seriously mentally ill. Eval. Program Plan. 1994, 17, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thara, R.; Padmavati, R.; Kumar, S.; Srinivasan, L. Instrument to assess burden on caregivers of chronic mentally ill. Indian J. Psychiatry 1998, 40, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Grässel, E.; Leutbecher, M. Häusliche Pflege-Skala: HPS; zur Erfassung der Belastung bei Betreuenden oder Pflegenden Personen; Vless: Ebersberg, Germany, 1993; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, L.; Ross, L.; Groenvold, M. The initial development of the ‘Cancer Caregiving Tasks, Consequences and Needs Questionnaire’ (CaTCoN). Acta Oncol. 2012, 51, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M.; Guest, C. Application of a Multidimensional Caregiver Burden Inventory1. Gerontologist 1989, 29, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmståhl, S.; Malmberg, B.; Annerstedt, L. Caregiver’s burden of patients 3 years after stroke assessed by a novel caregiver burden scale. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1996, 77, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, E.D.; Haut, M.W.; Keefover, R.W.; Franzen, M.D. The establishment of clinical cutoffs in measuring caregiver burden in dementia. Gerontologist 1994, 34, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boele, F.W.; Terhorst, L.; Prince, J.; Donovan, H.S.; Weimer, J.; Sherwood, P.R.; Lieberman, F.S.; Drappatz, J. Psychometric Evaluation of the Caregiver Needs Screen in Neuro-Oncology Family Caregivers. J. Nurs. Meas. 2019, 27, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, C.W.; Given, B.; Stommel, M.; Collins, C.; King, S.; Franklin, S. The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Res. Nurs. Health 1992, 15, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guberman, N.; Keefe, J.; Fancey, P.; Nahmiash, D.; Barylak, L. Development of Screening and Assessment Tools for Family Caregivers. Final Report NA 145 to Health Transition Fund, Health Canada; Health Transition Fund, Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association. AMA Homepage. Available online: https://www.ama-assn.org/ (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Robinson, B.C. Validation of a Caregiver Strain Index. J. Gerontol. 1983, 38, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.M.; Rakowski, W. Family caregivers of older adults: Improving helping skills. Gerontologist 1983, 23, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, S.; Fillion, L.; Gagnon, P.; Bernier, N. A new tool to assess family caregivers’ burden during end-of-life care. J. Palliat. Care 2008, 24, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P.; Kleban, M.H.; Moss, M.; Rovine, M.; Glicksman, A. Measuring Caregiving Appraisal. J. Gerontol. 1989, 44, P61–P71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, M.P.; Moss, M.; Kleban, M.H.; Glicksman, A.; Rovine, M. A two-factor model of caregiving appraisal and psychological well-being. J. Gerontol. 1991, 46, P181–P189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney, J.M.; Stephens, M.A.P. Caregiving Hassles Scale: Assessing the Daily Hassles of Caring for a Family Member With Dementia1. Gerontologist 1989, 29, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Castiglioni, C.; Bonanomi, A.; Graffigna, G. The Caregiving Health Engagement Scale (CHE-s): Development and initial validation of a new questionnaire for measuring family caregiver engagement in healthcare. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, K. Reconsidering the Caregiving Stress Appraisal scale: Validation and examination of its association with items used for assessing long-term care insurance in Japan. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2007, 44, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, H.; Coast, J.; Flynn, T.N. What do people value when they provide unpaid care for an older person? A meta-ethnography with interview follow-up. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, H.; Flynn, T.N.; Coast, J. Estimation of a preference-based carer experience scale. Med. Decis. Mak. 2011, 31, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, M.R.; Grant, G. Addressing the needs of informal carers: A neglected area of nursing practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 1989, 14, 950–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, C.; Higginson, I.; Jefferys, P. Carers Checklist; The Mental Health Foundation: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, K.J.; Philp, I.; Lamura, G.; Prouskas, C.; Oberg, B.; Krevers, B.; Spazzafumo, L.; Bień, B.; Parker, C.; Nolan, M.R.; et al. The COPE index--a first stage assessment of negative impact, positive value and quality of support of caregiving in informal carers of older people. Aging Ment. Health 2003, 7, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barusch, A.S. Problems and Coping Strategies of Elderly Spouse Caregivers1. Gerontologist 1988, 28, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, B.; Kinsella, G.J.; Picton, C. Development and initial validation of a family appraisal of caregiving questionnaire for palliative care. Psycho-Oncol. 2006, 15, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madianos, M.; Economou, M.; Dafni, O.; Koukia, E.; Palli, A.; Rogakou, E. Family disruption, economic hardship and psychological distress in schizophrenia: Can they be measured? Eur. Psychiatry J. Assoc. Eur. Psychiatr. 2004, 19, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Home Instead. S.C. Family Caregiver Distress Assessment Tool. Available online: https://www.caregiverstress.com/stress-management/family-caregiver-stress/stress-assessment/ (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Strömberg, A.; Bonner, N.; Grant, L.; Bennett, B.; Chung, M.L.; Jaarsma, T.; Luttik, M.L.; Lewis, E.F.; Calado, F.; Deschaseaux, C. Psychometric Validation of the Heart Failure Caregiver Questionnaire (HF-CQ®). Patient 2017, 10, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, C.E.; Powell, V.E.; Eldar-Lissai, A. Measuring hemophilia caregiver burden: Validation of the Hemophilia Caregiver Impact measure. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 2551–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, D.S.; Marmar, C.R. The Impact of Event Scale—Revised. In Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, R.E.K.; Riessman, C.K. The development of an impact-on-family scale: Preliminary findings. Med. Care 1980, 18, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, J.; Franzén-Dahlin, Å.; Billing, E.; Murray, V.; Wredling, R. Spouse’s life situation after partner’s stroke event: Psychometric testing of a questionnaire. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, M.; Travis, S.S. Analysis of the reliability of the modified caregiver strain index. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2003, 58, S127–S132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, R.J.; Borgotta, E.F. The effects of alternative support strategies on family caregiving. Gerontologist 1989, 29, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, R.J.; Gonyea, J.G.; Hooyman, N.R. Caregiving and the Experience of Subjective and Objective Burden. Fam. Relat. 1985, 34, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kashy, D.A.; Spillers, R.L.; Evans, T.V. Needs assessment of family caregivers of cancer survivors: Three cohorts comparison. Psycho-Oncol. 2010, 19, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- England, M.; Roberts, B.L. Theoretical and psychometric analysis of caregiver strain. Res. Nurs. Health 1996, 19, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asahara, K.; Momose, Y.; Murashima, S.; Okubo, N.; Magilvy, J.K. The relationship of social norms to use of services and caregiver burden in Japan. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2001, 33, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seniorplace. Selbsttest für Pflegende Angehörige. Available online: https://www.seniorplace.de/selbsttest.php#tab1 (accessed on 31 May 2020).

- Gaugler, J.E.; Anderson, K.A.; Leach, M.S.W.C.R.; Smith, C.D.; Schmitt, F.A.; Mendiondo, M. The emotional ramifications of unmet need in dementia caregiving. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Dement. 2004, 19, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernooij-Dassen, M.J.; Felling, A.J.; Brummelkamp, E.; Dauzenberg, M.G.; van den Bos, G.A.; Grol, R. Assessment of caregiver’s competence in dealing with the burden of caregiving for a dementia patient: A Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire (SSCQ) suitable for clinical practice. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1999, 47, 256–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S. Theoretical basis and application of the Social Support Rating Scale. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 4, 98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit, S.H.; Reever, K.E.; Bach-Peterson, J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 1980, 20, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Becker, S.; Becker, F.; Regel, S. Assessment of caring and its effects in young people: Development of the Multidimensional Assessment of Caring Activities Checklist (MACA-YC18) and the Positive and Negative Outcomes of Caring Questionnaire (PANOC-YC20) for young carers. Child Care Health Dev. 2009, 35, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiatti, C.; Di Rosa, M.; Melchiorre, M.G.; Manzoli, L.; Rimland, J.M.; Lamura, G. Migrant care workers as protective factor against caregiver burden: Results from a longitudinal analysis of the EUROFAMCARE study in Italy. Aging Ment. Health 2013, 17, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiatti, C.; Masera, F.; Rimland, J.M.; Cherubini, A.; Scarpino, O.; Spazzafumo, L.; Lattanzio, F. The UP-TECH project, an intervention to support caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients in Italy: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2013, 14, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein-Lubow, G.; Gaudiano, B.A.; Hinckley, M.; Salloway, S.; Miller, I.W. Evidence for the validity of the American Medical Association’s caregiver self-assessment questionnaire as a screening measure for depression. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, K.; Langman, A.; Winfield, H.; Catty, J.; Clement, S.; White, S.; Burns, E.; Burns, T. Measuring Outcomes for Carers for People with Mental Health Problems. Report for the National Coordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R & D (NCCSDO); National Institute for Health and Care Research: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hopia, H.; Latvala, E.; Liimatainen, L. Reviewing the methodology of an integrative review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 30, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsbach, K.D.; van Knippenberg, D. Creating High-Impact Literature Reviews: An Argument for ‘Integrative Reviews’. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 57, 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Sandberg, J. The Problematizing Review: A Counterpoint to Elsbach and Van Knippenberg’s Argument for Integrative Reviews. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 57, 1290–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, S.; Forbes, D.; Markle-Reid, M.; Hawranik, P.; Morgan, D.; Jansen, L.; Leipert, B.; Henderson, S. The Positive Aspects of the Caregiving Journey With Dementia: Using a Strengths-Based Perspective to Reveal Opportunities. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2010, 29, 640–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W.; White, K.M. “It Has Changed My Life”: An Exploration of Caregiver Experiences in Serious Illness. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. ® 2018, 35, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bom, J.; Bakx, P.; Schut, F.; van Doorslaer, E. The Impact of Informal Caregiving for Older Adults on the Health of Various Types of Caregivers: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2018, 59, e629–e642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoun, S.; Toye, C.; Deas, K.; Howting, D.; Ewing, G.; Grande, G.; Stajduhar, K. Enabling a family caregiver-led assessment of support needs in home-based palliative care: Potential translation into practice. Palliat. Med. 2015, 29, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sörensen, S.; Pinquart, M.; Duberstein, P. How Effective Are Interventions With Caregivers? An Updated Meta-Analysis. Gerontologist 2002, 42, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Hartmann, M.; Wens, J.; Verhoeven, V.; Remmen, R. The effect of caregiver support interventions for informal caregivers of community-dwelling frail elderly: A systematic review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2012, 12, e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploeg, J.; Ali, M.U.; Markle-Reid, M.; Valaitis, R.; Bartholomew, A.; Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D.; McAiney, C.; Sherifali, D. Caregiver-Focused, Web-Based Interventions: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (Part 2). J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e11247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiers, G.F.; Liddle, J.; Kunonga, T.P.; Whitehead, I.O.; Beyer, F.; Stow, D.; Welsh, C.; Ramsay, S.E.; Craig, D.; Hanratty, B. What are the consequences of caring for older people and what interventions are effective for supporting unpaid carers? A rapid review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krutter, S.; Schaffler-Schaden, D.; Essl-Maurer, R.; Wurm, L.; Seymer, A.; Kriechmayr, C.; Mann, E.; Osterbrink, J.; Flamm, M. Comparing perspectives of family caregivers and healthcare professionals regarding caregiver burden in dementia care: Results of a mixed methods study in a rural setting. Age Ageing 2019, 49, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firmawati, E.; Setyopanoto, I.; Pangastuti, H.S. Mobile Health Application to Support Family Caregivers in Recurrent Stroke Prevention: Scoping Review. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 9, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Howell, D.; Shen, N.; Geng, Z.; Wu, F.; Shen, M.; Zhang, X.; Xie, A.; Wang, L.; Yuan, C. mHealth Supportive Care Intervention for Parents of Children With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Quasi-Experimental Pre- and Postdesign Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidegger, A.; Müller, M.; Arrer, E.; Fringer, A. Das dynamische Modell der Angehörigenpflege und -betreuung. Z. Für Gerontol. Und Geriatr. 2019, 53, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, R.J.V.; Kosloski, K.D. Pathways to a caregiver identity and implications for support service. In Caregiving across the Lifespan. Research, Practice, Policy; Talley, R.C., Montgomery, R.J.V., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 131–156. [Google Scholar]

- Weskamm, A.; Keßler, I.S.; Marks, F. German professional association for nursing professions DBfK. In Booklet: Community Health Nursing in Deutschland. Eine Chance für die Bessere Gesundheitsversorgung in den Kommunen; Deutscher Berufsverband für Pflegeberufe DBfK, Ed.; Agnes-Karll-Gesellschaft für Gesundheitsbildung und Pflegeforschung mbH: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, P.; Quinn, K.; Kristjanson, L.; Thomas, T.; Braithwaite, M.; Fisher, J.; Cockayne, M. Evaluation of a psycho-educational group programme for family caregivers in home-based palliative care. Palliat. Med. 2008, 22, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivarsson, A.-B.; Sidenvall, B.; Carlsson, M. The factor structure of the Burden Assessment Scale and the perceived burden of caregivers for individuals with severe mental disorders. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2004, 18, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secinti, E.; Yavuz, H.M.; Selcuk, B. Feelings of burden among family caregivers of people with spinal cord injury in Turkey. Spinal Cord 2017, 55, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadda, R.K.; Singh, T.B.; Ganguly, K.K. Caregiver burden and coping: A prospective study of relationship between burden and coping in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2007, 42, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, N.; Ali, A.; Deuri, S.P. A comparative study of care burden and social support among caregivers of persons with schizophrenia and epilepsy. Open J. Psychiatry Allied Sci. 2015, 6, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auzinger, M. Physische und psychische Belastungen pflegender Angehöriger im Bezirk Braunau am Inn; UMIT, Hall in Tirol. 2009. Available online: https://www.oegkv.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Publikationen/Diplomarbeiten/AUZINGER_Maria_DA2009_Physische_und_psychische_Belastungen_pflegender_Angehoeriger_im_Bezirk_Braunau_am_Inn.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Brogaard, T.; Neergaard, M.A.; Guldin, M.-B.; Sokolowski, I.; Vedsted, P. Translation, adaptation and data quality of a Danish version of the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2013, 27, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grässel, E.; Berth, H.; Lichte, T.; Grau, H. Subjective caregiver burden: Validity of the 10-item short version of the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers BSFC-s. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grässel, E. Somatic symptoms and caregiving strain among family caregivers of older patients with progressive nursing needs. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 1995, 21, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grässel, E.; Chiu, T.; Oliver, R. Development and Validation of the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers (BSFC); Comprehensive Rehabilitation and Mental Health Services: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Grässel, E. "Burden Scale for Family Caregivers" in 20 Sprachen, o.J. Available online: www.caregiver-burden.eu (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Grässel, E. Häusliche Pflege dementiell und nicht dementiell Erkrankter. Teil II: Gesundh. Und Belast. Der Pflegenden. Z. Für Gerontol. Und Geriatr. 1998, 31, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grässel, E. HPS—Häusliche Pflege-Skala; Hogrefe: Bern, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grässel, E.; Behrndt, E.-M. Belastungen und Entlastungsangebote für pflegende Angehörige. Pflege-Report 2016: Die Pflegenden im Fokus. Available online: https://www.wido.de/fileadmin/Dateien/Dokumente/Publikationen_Produkte/Buchreihen/Pflegereport/2016/Kapitel%20mit%20Deckblatt/wido_pr2016_kap11.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Grau, H.; Graessel, E.; Berth, H. The subjective burden of informal caregivers of persons with dementia: Extended validation of the German language version of the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers (BSFC). Aging Ment. Health 2015, 19, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, M.J.; Graesel, E.; Tigges, S.; Hillemacher, T.; Winterholler, M.; Hilz, M.-J.; Heuss, D.; Neundörfer, B. Burden of care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Palliat. Med. 2003, 17, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, K.; Miksch, A.; Peters-Klimm, F.; Engeser, P.; Szecsenyi, J. Correlation between patient quality of life in palliative care and burden of their family caregivers: A prospective observational cohort study. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamparter, C. Die Belastung pflegender Angehöriger: Entwicklung eines Instrumentes zur Belastungseinschätzung pflegender Angehöriger von Demenzerkrankten. 2019. Available online: https://dg-pflegewissenschaft.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Session-7-Pr%C3%A4sentation-Carmen-Lamparter.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- Pendergrass, A.; Malnis, C.; Graf, U.; Engel, S.; Graessel, E. Screening for caregivers at risk: Extended validation of the short version of the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers (BSFC-s) with a valid classification system for caregivers caring for an older person at home. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, L.; Ross, L.; Petersen, M.A.; Groenvold, M. The validity and reliability of the ‘Cancer Caregiving Tasks, Consequences and Needs Questionnaire’ (CaTCoN). Acta Oncol. 2014, 53, 966–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavagli, V.; Raccichini, M.; Ercolani, G.; Franchini, L.; Varani, S.; Pannuti, R. Care for Carers: An Investigation on Family Caregivers' Needs, Tasks, and Experiences. Transl. Med. 2019, 19, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Akpınar, B.; Küçükgüçlü, O.; Yener, G. Effects of gender on burden among caregivers of Alzheimer's patients. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2011, 43, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caserta, M.S.; Lund, D.A.; Wright, S.D. Exploring the Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI): Further evidence for a multidimensional view of burden. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 1996, 43, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, W.T.; Lee, I.Y.M. Randomized controlled trial of a dementia care programme for families of home-resided older people with dementia. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiò, A.; Vignola, A.; Mastro, E.; Dei Giudici, A.; Iazzolino, B.; Calvo, A.; Moglia, C.; Montuschi, A. Neurobehavioral symptoms in ALS are negatively related to caregivers' burden and quality of life. Eur. J. Neurol. 2010, 17, 1298–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Onofrio, G.; Sancarlo, D.; Addante, F.; Ciccone, F.; Cascavilla, L.; Paris, F.; Picoco, M.; Nuzzaci, C.; Elia, A.C.; Greco, A.; et al. Caregiver burden characterization in patients with Alzheimer's disease or vascular dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; Catapano, M.A.; Brooks, D.; Goldstein, R.S.; Avendano, M. Family caregiver perspectives on caring for ventilator-assisted individuals at home. Can. Respir. J. 2012, 19, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fianco, A.; Sartori, R.D.G.; Negri, L.; Lorini, S.; Valle, G.; Delle Fave, A. The relationship between burden and well-being among caregivers of Italian people diagnosed with severe neuromotor and cognitive disorders. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 39, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, A.; Vignola, A.; Calvo, A.; Cavallo, E.; Moglia, C.; Sellitti, L.; Mutani, R.; Chiò, A. A longitudinal study on quality of life and depression in ALS patient-caregiver couples. Neurology 2007, 68, 923–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, A.; Pancani, L.; Sala, M.; Annoni, A.M.; Steca, P.; Paturzo, M.; D'Agostino, F.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E. Psychometric characteristics of the caregiver burden inventory in caregivers of adults with heart failure. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2017, 16, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iavarone, A.; Ziello, A.R.; Pastore, F.; Fasanaro, A.M.; Poderico, C. Caregiver burden and coping strategies in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.; Cipriani, M.; Renzi, A.; Luciani, M.; Lombardo, L.; Aceto, P. The Effects of the Perception of Being Recognized by Patients With Alzheimer Disease on a Caregiver's Burden and Psychophysical Health. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2018, 35, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marvardi, M.; Mattioli, P.; Spazzafumo, L.; Mastriforti, R.; Rinaldi, P.; Polidori, M.C.; Cherubini, A.; Quartesan, R.; Bartorelli, L.; Bonaiuto, S.; et al. The Caregiver Burden Inventory in evaluating the burden of caregivers of elderly demented patients: Results from a multicenter study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2005, 17, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCleery, A.; Addington, J.; Addington, D. Family assessment in early psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2007, 152, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merluzzi, T.V.; Philip, E.J.; Vachon, D.O.; Heitzmann, C.A. Assessment of self-efficacy for caregiving: The critical role of self-care in caregiver stress and burden. Palliat. Support. Care 2011, 9, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reckrey, J.M.; DeCherrie, L.V.; Kelley, A.S.; Ornstein, K. Health Care Utilization Among Homebound Elders. J. Aging Health 2013, 25, 1036–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, E.; Ambrogio, M.; Binetti, G.; Zanetti, O. 'Immigrant paid caregivers' and primary caregivers' burden. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2004, 19, 1103–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinforiani, E.; Pasotti, C.; Chiapella, L.; Malinverni, P.; Zucchella, C. Differences between physician and caregiver evaluations in Alzheimer's disease. Funct. Neurol. 2010, 25, 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Tramonti, F.; Barsanti, I.; Bongioanni, P.; Bogliolo, C.; Rossi, B. A permanent emergency: A longitudinal study on families coping with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Fam. Syst. Health 2014, 32, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andren, S.; Elmstahl, S. Family caregivers' subjective experiences of satisfaction in dementia care: Aspects of burden, subjective health and sense of coherence. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2005, 19, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annerstedt, L.; Elmståhl, S.; Ingvad, B.; Samuelsson, S.M. Family caregiving in dementia—An analysis of the caregiver's burden and the "breaking-point" when home care becomes inadequate. Scand. J. Public Health 2000, 28, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belasco, A.; Barbosa, D.; Bettencourt, A.R.; Diccini, S.; Sesso, R. Quality of life of family caregivers of elderly patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2006, 48, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cil Akinci, A.; Pinar, R. Validity and reliability of Turkish Caregiver Burden Scale among family caregivers of haemodialysis patients. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmstahl, S.; Ingvad, B.; Annerstedt, L. Family caregiving in dementia: Prediction of caregiver burden 12 months after relocation to group-living care. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1998, 10, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashayekhi, F.; Jozdani, R.H.; Chamak, M.N.; Mehni, S. Caregiver Burden and Social Support in Mothers with β-Thalassemia Children. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2016, 8, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olai, L.; Borgquist, L.; Svärdsudd, K. Life situations and the care burden for stroke patients and their informal caregivers in a prospective cohort study. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2015, 120, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redinbaugh, E.M.; Baum, A.; Tarbell, S.; Arnold, R. End-of-life caregiving: What helps family caregivers cope? J. Palliat. Med. 2003, 6, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggar, C.; Ronaldson, S.; Cameron, I.D. Reactions to caregiving during an intervention targeting frailty in community living older people. BMC Geriatr. 2012, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachner, Y.G.; O'Rourke, N.; Carmel, S. Psychometric properties of a modified version of the Caregiver Reaction Assessment Scale measuring caregiving and post-caregiving reactions of caregivers of cancer patients. J. Palliat. Care 2007, 23, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudgeon, D.J.; Knott, C.; Eichholz, M.; Gerlach, J.L.; Chapman, C.; Viola, R.; van Dijk, J.; Preston, S.; Batchelor, D.; Bartfay, E. Palliative Care Integration Project (PCIP) quality improvement strategy evaluation. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2008, 35, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Frias, C.M.; Tuokko, H.; Rosenberg, T. Caregiver physical and mental health predicts reactions to caregiving. Aging Ment. Health 2005, 9, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaugler, J.E.; Hanna, N.; Linder, J.; Given, C.; Tolbert, V.; Kataria, R.; Regine, W.F. Cancer caregiving and subjective stress: A multi-site, multi-dimensional analysis. Psycho-Oncol. 2005, 14, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grater, J.J. The Impact of Health Care Provider Communication on Self-Efficacy and Caregiver Burden in Older Spousal Oncology Caregivers. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh. (Unpublished). Available online: http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/9303/ (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Grov, E.K.; Eklund, M.L. Reactions of primary caregivers of frail older people and people with cancer in the palliative phase living at home. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 63, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grov, E.K.; Fosså, S.D.; Sørebø, O.; Dahl, A.A. Primary caregivers of cancer patients in the palliative phase: A path analysis of variables influencing their burden. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 2429–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grov, E.K.; Fosså, S.D.; Tønnessen, A.; Dahl, A.A. The caregiver reaction assessment: Psychometrics, and temporal stability in primary caregivers of Norwegian cancer patients in late palliative phase. Psycho-Oncol. 2006, 15, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, P.L.; Thomas, K.; Trauer, T.; Remedios, C.; Clarke, D. Psychological and social profile of family caregivers on commencement of palliative care. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2011, 41, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, Y.; Miyashita, M.; Sato, K.; Ozawa, T. Family's Difficulty Scale in End-of-Life Home Care: A New Measure of the Family's Difficulties in Caring for Patients with Cancer at the End of Life at Home from Bereaved Family's Perspective. J. Palliat. Med. 2012, 15, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]