Abstract

Considering the rising life expectancy, the growing population of older adults poses challenges in providing adequate healthcare services. Self-reported health is an important indicator of overall health, predicting morbidity and mortality. This study investigated self-reported health inequalities among older adults in Saudi Arabia and the underlying factors contributing to establishing such inequalities. The study utilized data from the 2018 Saudi Family Health Survey, focusing on 2023 respondents aged ≥60 years with complete data. Univariate, bivariate, and multivariate logistic regression analyses were employed to explore socio-economic factors linked to health inequalities. Additionally, concentration curves and indices were used to assess the magnitude of health inequalities among older adults. The findings indicate a higher prevalence of self-reported poor health among respondents aged ≥70 years and those with chronic diseases. Age, education, income level, marital status, and insurance coverage were other factors significantly linked to reporting poor health. Inequality analysis revealed a concentration of poor health among less educated individuals (concentration index = −0.261, p < 0.01). Both income- and education-based indices highlighted a concentration of poor health among men with lower income and education levels. Addressing healthcare inequalities among older adults requires targeted policy efforts, focusing on those aged ≥70, unmarried individuals, those without insurance coverage, those with chronic illnesses, and those with lower education levels. Targeted interventions for these groups can address their unique healthcare needs and promote equitable health outcomes.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, global population aging has accelerated significantly, with people now living longer than before. Projections suggest that from 2015 to 2050, the percentage of individuals aged over 60 years will nearly double, increasing from 12% to 22% of the world’s population [1]. While the shift toward an aging population reflects progress in healthcare and societal development, it also poses challenges, particularly in ensuring healthcare access for older adults. The health of the population tends to decline gradually from early adulthood to retirement age [2]. Accumulated hazardous exposures and lifestyle changes influenced by societal advancements contribute to this phenomenon [3]. The older population faces higher health risk factors but encounters systematic challenges in healthcare access compared to younger age groups [4,5]. With escalating healthcare spending, the health challenges of older adults pose additional complexities for the healthcare system.

Health inequalities encompass variations and disparities in health outcomes among a population [6]. Such disparities may arise when society fails to mitigate conditions for disadvantaged groups. Self-reported health is an important indicator of overall health, predicting morbidity and mortality [7]. Research indicates that lower socio-economic groups tend to self-report being in poor health more frequently than other demographic groups [8,9]. Public health policies must therefore aim to address these inequalities, particularly to improve the health of vulnerable groups [10]. Besides lower socio-economic status, older adults are also considered to be a vulnerable group due to the natural decline in health and physical strength associated with aging [11]. The continuous rise in the older population has an impact on various aspects of healthcare, including staffing, care costs, program availability, and service provision [12]. Older individuals often face challenges in accessing necessary preventive, diagnostic, treatment, and management healthcare services [3,13]. From an economic perspective, population aging has a negative impact on economic growth due to increased pensions, per capita healthcare expenditures, and the indirect influence on national funding in other domains [14,15].

The impact of population aging is particularly significant in the Arab world, where the older population is projected to reach the highest proportion of the total population by 2050 [16]. In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), the trend of population aging is prominent, with the number of individuals aged ≥65 years projected to continue growing. By 2050, this age group is anticipated to comprise 18.4% of the country’s total population [14]. This is attributable to the KSA’s notable advancements in enhancing the health standards of its population compared to other countries in Western Asia [17]. Nevertheless, the public healthcare services in the KSA face the challenges of being overburdened and overcrowded [18]. As such, the country is likely to encounter additional difficulties arising from population aging [19].

Although the implications of the aging population are significant for the KSA, there is a scarcity of literature regarding the health status of older adults in the country. Existing research has primarily focused on the burden experienced by informal caregivers of older individuals [20], non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among the older population [19], and the perspectives of older individuals on health [14]. In the context of health inequalities in the KSA, existing literature has explored determinants through a systematic review [21], socio-economic inequalities in diabetes prevalence [22], gender-based health inequalities [23], and socio-economic variations in dental service utilization [24]. Nevertheless, these studies, besides their limited scope and lack of empirical techniques, do not specifically address health inequalities among older adults.

To fill this gap, this study examined self-reported health inequalities among older adults (aged ≥ 60 years) in the KSA, aiming to identify its existence and explore the underlying factors contributing to these inequalities. Data from the 2018 Saudi Family Health Survey (FHS) were utilized for this analysis. Employing univariate, bivariate, and multivariate logistic regression analyses, we aimed to identify socio-economic factors linked to self-reporting being in “poor” or “good” health among the older generation to determine the existence of health inequalities and the contributing factors. Additionally, concentration curves and indices were used to assess the magnitude of health inequalities among older adults participating in the survey.

This study focuses on Saudi Arabian individuals aged 60 years and above, thereby contributing to the existing literature in multiple ways. Firstly, it evaluates the applicability of international findings on older adults to the specific context of the KSA. Secondly, it employs empirical techniques to enhance and complement findings from previous studies lacking such investigative methods. Thirdly, in contrast to studies with narrower scopes, this research examines health inequalities across various socio-economic characteristics. Lastly, given the increasing trend of population aging in the country, this research adds knowledge about the overall health status of older adults, with implications for policymaking regarding their health outcomes. In general, this study offers insights that can inform the formulation of public policies and interventions geared toward improving healthcare services, with a particular focus on addressing the needs of older adults facing socio-economic disadvantages.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Sample

This study used nationally representative secondary data obtained from the 2018 Saudi FHS conducted by the General Authority for Statistics (GaStat) [25]. The FHS is a field survey classified under the categories of education and health statistics, representing a collaboration between the GaStat, Ministry of Health, Saudi Health Council, academic institutes, and the private sector. Surveys were completed based on visits to 15,265 individuals who were randomly selected across all 13 administrative regions of the KSA using a two-stage sampling approach to obtain a representative sample of the entire population.

The survey contains questions related to geography, health status, health utilization, and chronic diseases, among other topics addressing family and health issues. Several health variables were considered in the present study, with a focus on the report of self-assessed health status. The present analysis was limited to data obtained only from respondents aged ≥ 60 years who provided complete information on all variables of interest, resulting in an analyzed sample of 2023 respondents.

2.2. Measurement Variables

In the FHS, the self-reported health (SRH) status was determined from the following question: “how do you classify your health in general, which includes both your physical and mental health?”. The responses were scored on a 5-point scale: “Very good”, “Good”, “Mediocre”, “Bad”, and “Very bad”. SRH status was used as the outcome variable for examining the socio-economic determinants and health inequalities among older adults in the KSA. To facilitate the bivariate analysis, the 5-point scale was converted to a binary outcome of 0 and 1, with 0 representing responses “Very good”, “Good” and “Mediocre” as good health, and 1 representing the responses “Bad” and “Very bad” as poor health [26,27,28].

Independent variables considered in the model were socio-economic and demographic characteristics such as age, gender, marital status, nationality, education level, monthly income, health insurance coverage, and the existence of chronic illness. Among these, income and education level served as the indicators of socio-economic status. Respondents were classified into two age categories: younger (60 to 69 years) coded 0 and older (≥70 years) coded 1. Gender (1 for man and 0 for woman), marital status (1 for married and 0 for unmarried, including never married, divorced, and widowed), nationality (1 for Saudi and 0 for non-Saudi), health insurance (1 covered and 0 not covered), and chronic illness status (1 present and 0 absent) were all captured as binary variables. Education level was divided into five groups: below primary school (reference), primary school, intermediate school, high school, and higher education. Monthly income (in Saudi Riyal (SR); 1 SR = USD 0.27) was grouped into eight categories: <3000 (reference category), 3000 to <5000, 5000 to <7000, 7000 to <10,000, 10,000 to <15,000, 15,000 to <20,000, 20,000 to <30,000, and ≥30,000.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The analysis for this study was conducted in various steps. Initially, univariate analyses were performed to evaluate the relative frequencies of respondents for each characteristic. Bivariate analysis was performed for the cross-tabulation of the dependent variable (SRH) with the associated frequencies using a Chi-squared test. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to examine the independent associations of socio-economic factors with SRH controlling for age, gender, marital status, nationality, health insurance coverage, and chronic illness status. Socio-economic health inequalities at the national level and in each socio-economic group (according to income and education levels) were evaluated based on the construction of the concentration curve and the calculation of the concentration index according to the methodology of Wagstaff et al. [29].

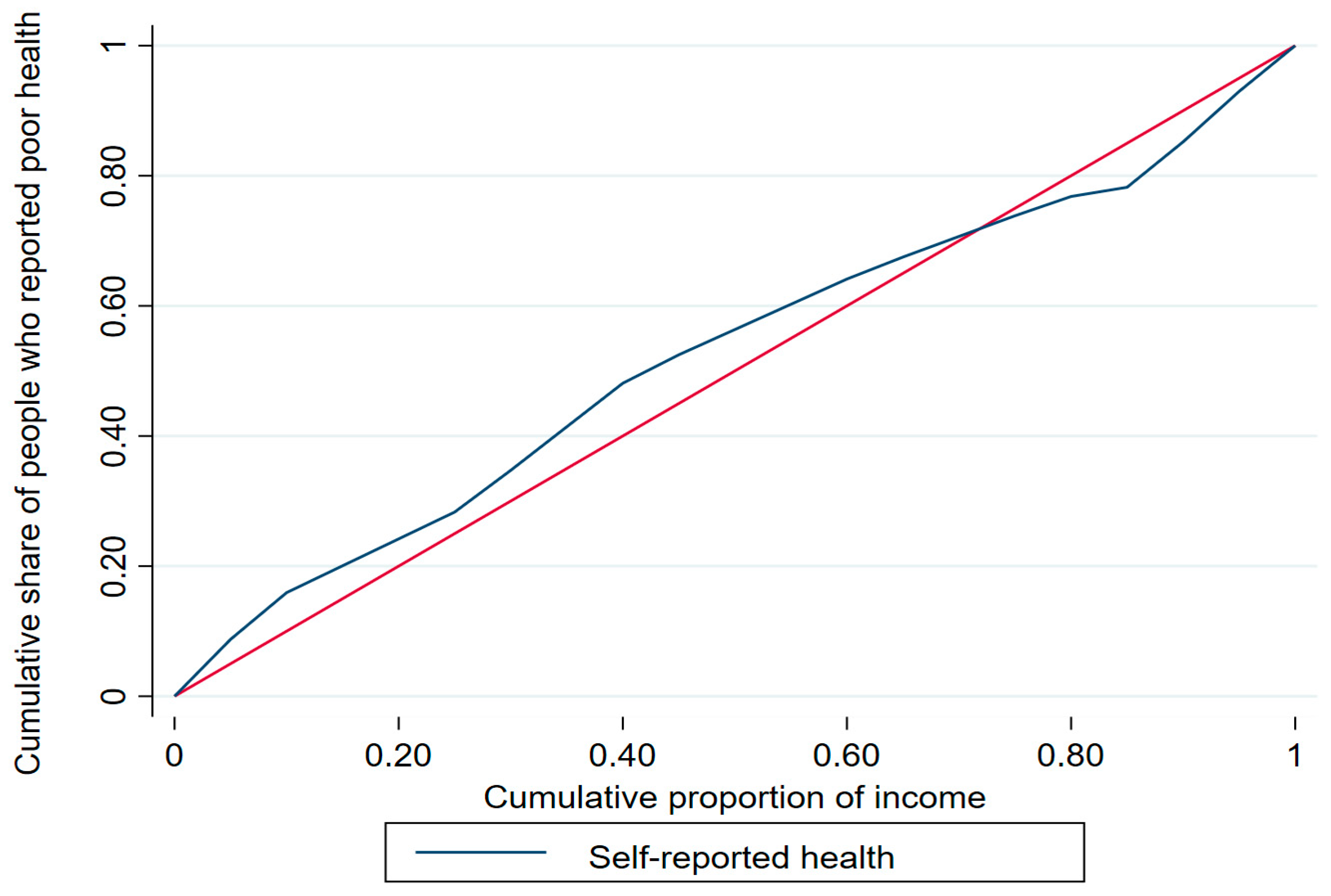

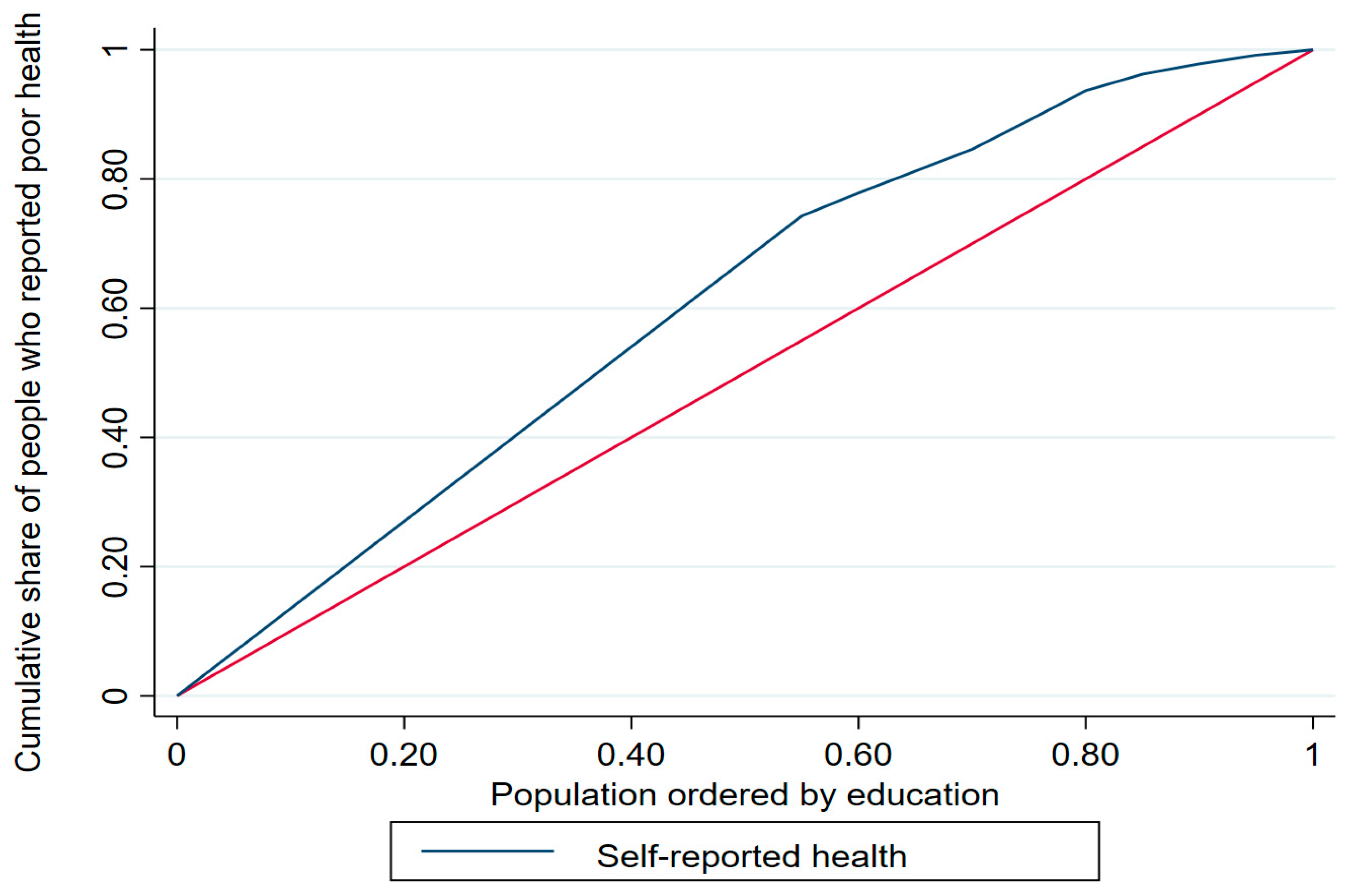

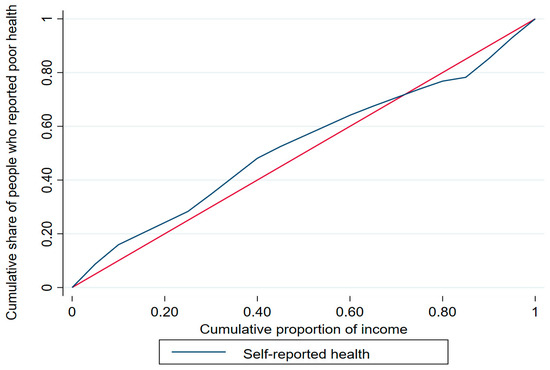

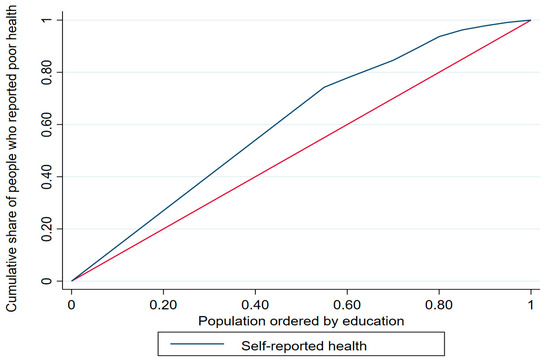

The concentration index (ranging from −1 to +1) is calculated as twice the area between the concentration curve and the line of equality [30], whereby a positive index value indicates that a given health variable is disproportionately concentrated among the rich/highly educated and a negative index value indicates concentration among the poor/less educated. The concentration curve offers a visual representation of the degree of inequality in SRH by plotting the cumulative percentage of a health variable with respect to the cumulative share of that variable in the population (variables are ranked according to a socio-economic status indicator from the lowest to the highest) [30]. For example, with respect to income and education level, a curve above the line of equality (i.e., the 45-degree line) indicates that poor health status is concentrated among those with lower income/less education, whereas a concentration curve below the line of equality indicates that poor health status is concentrated among those with higher income/higher education. The further the concentration curve diverges from the line of equality, the greater the degree of inequality.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The socio-demographic characteristics of the analyzed respondents are presented in Table 1. Among the total sample of 2023 respondents aged ≥60 years, 17.35% rated their health status as poor, while 82.65% rated their health status as good. Over half of the respondents were men, three-quarters were married, over half had an education level below primary school, approximately 21% of the respondents earned 15,000 SR and more, around three-quarters were covered by health insurance, and the majority (85.91%) were suffering from a chronic illness.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the sample (n = 2023).

3.2. Bivariate Analysis

The results of the bivariate analysis between SRH and socio-economic characteristics are presented in Table 2. Poor health status was significantly associated with age (χ2 = 46.05, p < 0.01), which was mainly concentrated among the older respondents (aged ≥ 70 years; 23.61%) compared to the younger respondents (60–69 years; 12.14%). Gender (χ2 = 32.23, p < 0.01), marital status (χ2 = 51.17, p < 0.01), and educational attainment (χ2 = 78.72, p < 0.01) were significantly associated with reporting a poor health status. In particular, the frequency of reporting a poor health status was much lower (2.94%) among people with a higher education than among respondents with below primary school (23.43%) or primary school (11.73%) education. Moreover, reporting a poor health status was significantly associated with health insurance status (χ2 = 33.58, p < 0.01), which was mainly concentrated among the uninsured (20.37%) compared to the insured (9.46%). Similarly, reporting a poor health status was significantly associated with chronic illness status (χ2 = 35.79, p < 0.01), in which reporting a poor health status was more heavily concentrated among those suffering from chronic diseases (19.39%) than those not suffering from chronic diseases (4.91%).

Table 2.

Bivariate analysis of self-reported health and socio-economic characteristics (n = 2023).

The Wagstaff inequality concentration index values to quantify the level of inequalities in SRH across socio-economic categories (i.e., income and education) are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Wagstaff inequality indices for self-reported health by income and education level (n = 2023).

The overall education-based concentration index was −0.261, which was statistically significant at the 1% level, demonstrating a greater tendency to report poor health status among the less-educated respondents in the KSA. Gender also impacted both income-based and education-based concentration indices, with poor health status concentrated among men with lower income and lower education levels. Age was a significant factor negatively associated with education-based concentration indices, whereas the income-based concentration index for the younger group (60–69 years) was positive, indicating a greater concentration of poor health status among those in their 60s with a higher income level.

The concentration curves for income and education are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. The income-based concentration curve for poor health status (blue) almost overlaps with the line of equality (red), suggesting no inequality, whereas the education-based concentration curve is above the line of equality, confirming the prevalence of poor health status among the less educated older adults in the KSA.

Figure 1.

Income-based concentration curve.

Figure 2.

Education-based concentration curve.

3.3. Regression Analysis

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to consider the potential influence of other variables on the association between poor health status and socio-economic factors. Table 4 summarizes the results. Model 1 showed that the likelihood of reporting a poor health status was lower among all income groups (except those who earn 20,000 to 30,000 and ≥30,000 SR) when compared with the lower income group (earning below 3000 SR). For example, the odds ratio (OR) was 0.247 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.104–0.586; p ˂ 0.01) for people with a reported income level of 15,000 to <20,000 SR. Model 2 indicated the lower likelihood of reporting a poor health status among people with a higher education level (OR: 0.225, 95% CI: 0.078–0.645; p ˂ 0.01) when compared with less educated people (below the primary school level of education). The OR of education categories remained statistically significant in Model 3, along with a greater likelihood of reporting a poor health status among people aged ≥70 years (OR: 2.035, 95% CI: 1.547–2.675; p ˂ 0.01) when compared with that of the younger group aged 60–69 years.

Table 4.

Association between poor health status and socio-economic factors (logistic regression).

In addition, married respondents had a lower likelihood of reporting a poor health status (OR: 0.566, 95% CI: 0.393–0.815; p ˂ 0.01) when compared with unmarried respondents, indicating that reporting a poor health status was almost 0.57 times lower for those who are married than for those who are unmarried. Moreover, the likelihood of reporting poor health status among those with health insurance coverage was lower when compared with that of those who are not insured (OR: 0.480, 95% CI: 0.335–0.687; p ˂ 0.01). Model 3 also revealed the higher likelihood of reporting poor health status among those with a chronic illness (OR: 4.089, 95% CI: 2.305–7.251; p ˂ 0.01) when compared with those not suffering from a chronic illness, suggesting that those with a chronic illness were 4.1 times more likely to report a poor health status when compared with those not suffering from a chronic illness.

4. Discussion

This study examined the self-reported health inequalities among older adults (≥60 years) in the KSA and explored the underlying factors driving the occurrence of this phenomenon. By utilizing a rich dataset from the 2018 Saudi FHS, which provides an advantage of national representativeness, this study offers a detailed analysis of health inequalities. To ensure that the results of this study would be reliable and robust, multiple techniques were employed, including descriptive analysis using percentages and frequencies, bivariate analysis using the Chi-square test, inequality analysis using the Wagstaff concentration index, and regression analysis using the logistic model. These methodologies strengthen the findings, thereby maintaining their policy relevance in informing interventions aimed at addressing health inequalities among the older population.

Age was a significant factor associated with self-reporting poor health, showing a higher prevalence among individuals aged ≥70 (23.61%) compared to those in the younger group (60–69 years). This finding aligns with the existing literature indicating an increasing prevalence of poor health with increasing age [28,31,32]. For instance, a study in Brazil found an association of age with mortality in older men, with each additional year increasing the risk of death by 5% [33]. In the KSA, the observed poor health among older adults is consistent with the overall high prevalence of NCDs in the adult population [19,34]. Factors such as limited physical activity, unhealthy habits, financial constraints, and limited access to specialized care contribute to the hindered health status of older individuals. Additionally, research conducted by Haseen et al. [32] and Molarius et al. [35] emphasizes that the natural aging process leads to functional limitations and a weakened immune system, both of which negatively impact the health status of older individuals. Therefore, it is essential to educate the population on practical health measures to alleviate the impact of the aging process.

Significant associations were found between reporting a poor health status and marital status. Marriage was associated with a lower likelihood of self-reporting a poor health status compared to unmarried individuals, indicating an approximately 0.57 times lower likelihood of self-reporting a poor health status for married individuals. Unmarried older individuals, who live alone, often experience lower social participation, accompanied by increased feelings of loneliness given the lack of emotional and practical support at home [36]. This finding aligns with a previous study showing that family interactions were viewed as crucial by older individuals in the KSA [14]. The absence of spousal support may contribute to poor dietary habits and an undisciplined lifestyle, ultimately leading to poor health among the older population [37]. Implementing public policies that enhance marriages and family care systems can decrease the likelihood of unhealthy lifestyles derived from loneliness.

Furthermore, a significant association was observed between reporting a poor health status and educational attainment. Logistic regression analysis revealed that individuals with higher education had a lower likelihood of reporting a poor health status compared to those with below primary school education. The statistical significance (1% probability) of the overall education-based concentration index highlights a concentration of poor health among less-educated individuals in the KSA. Although Brinda et al. [38] found no association between education and poor health status, other studies have confirmed this relationship [39,40]. This is expected as individuals with higher education tend to possess greater awareness about diseases and their impacts, along with better availability and access to quality health services, which explains their better health reporting. Advocating for policies that promote higher education levels in the population would contribute to addressing poor health.

Moreover, there was a significant association between reporting a poor health status and health insurance coverage status. The concentration of reporting a poor health status was higher among uninsured individuals (20.37%) compared to those with insurance coverage (9.46%). The likelihood of reporting a poor health status was also lower among those with health insurance compared to those without insurance in the logistic regression. Although Fonta et al. [28] found no significant difference in SRH between insured and uninsured older individuals, Kunna et al. [4] emphasized that the absence of health insurance coverage contributed to approximately 12% of observed health inequalities. Therefore, in addition to old age being a predisposing factor for poor health, access to health insurance is an important consideration for governments to enhance the health situation of the older population. The absence of insurance increases the likelihood of facing significant out-of-pocket expenses, which can result in catastrophic health expenditure among the aging population [41]. Similarly, there was a significant association between reporting a poor health status and chronic illness. Individuals suffering from chronic diseases had a higher likelihood of reporting a poor health status compared to those not suffering from chronic diseases, indicating that individuals with chronic conditions were approximately 4.1 times more likely to report a poor health status. This finding aligns with previous studies as the presence of a chronic illness places a burden on healthcare expenses and is often accompanied by the reporting of poor health status [42].

Lastly, the likelihood of reporting a poor health status was lower among higher income groups, except for those earning between 20,000 to 30,000 SR and those earning ≥ 30,000 SR, in comparison to the lower income group earning below 3000 SR. Similar findings were reported in China [43], Brazil [33,39], and Mexico [44]. Read et al. [45] found a significant association between self-reporting poor health, low income, and general poor socio-economic status among older individuals in Europe. Achdut and Sarid [46] argued that low income can hinder social participation and lead to poorer health outcomes for older adults. Melchiorre [47] highlighted the impact of worry, depression, and stress on the health of older individuals, particularly when facing financial constraints. A stable source of income during old age enhances social status, living conditions, and reduces worries. These findings underscore the importance of addressing income inequalities and providing financial support to improve the health and well-being of older adults.

This study possesses several notable strengths. The results are based on a comprehensive dataset that represents the entire nation, focusing exclusively on the health of the older population (≥60 years) of the KSA. Multiple techniques were employed to mitigate potential biases and enhance the validity of the findings and conclusions. As a result, the study holds relevance for informing policy design and implementation aimed at addressing health inequalities among the aging population. However, certain limitations are also associated with this study. Recall and individual biases are possible given the nature of the self-reported data. Future analyses could benefit from incorporating alternative data sources or employing standardized measures to minimize the impact of self-reporting. Additionally, due to its cross-sectional nature, the study cannot establish definitive causal relationships between the investigated factors and poor health.

5. Conclusions

Using the 2018 Saudi FHS and multiple analytical techniques, this study examined inequalities in self-reported health among older adults in the KSA and the factors that drive this inequality. The study highlights a high occurrence of self-reported poor health in individuals aged ≥70 years, particularly those grappling with chronic diseases. Moreover, there is a clustering of poor health among individuals with lower levels of education and those with limited income. The study has implications for research, policy, and practice. Firstly, concerning research implications, the study underscores the significance of examining inequality within specific segments of the population. This approach yields insights that may be overlooked when research focuses on general health inequalities. Furthermore, future studies could attempt to use panel data, observing adults over time, to progress toward establishing causal relationships. Secondly, in terms of policy and practice implications, the study highlights that some subgroups among the older population, especially those grappling with chronic diseases, face greater vulnerability and require targeted assistance. Therefore, the government needs to prioritize the implementation of social and health promotion programs that actively support these subpopulations of older adults in the KSA. To mitigate the health effects of aging, as indicated by this study, programs should focus on enhancing physical activity, promoting better nutrition, and addressing feelings of loneliness. By focusing on primary prevention measures, healthy aging can be promoted, ensuring the long-term sustainability of healthcare systems. Safeguarding the health of the older population will not only improve their well-being but also contribute to reduced government expenditure on healthcare funds.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures involving human participants complied with institutional and/or national research committee ethical standards and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and subsequent amendments or equivalent ethical standards. GaStat removed all personal identifiers from the dataset prior to secondary data use. GaStat managed the data obtained from the FHS and granted permission for secondary use at the data collection stage; thus, no further ethical approval was necessary.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study by GaStat.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy, confidentiality, and other restrictions. Access to data can be gained through the General Authority for Statistics in Saudi Arabia via https://www.stats.gov.sa/en.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO. World Health Organization: Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Shang, X.; Wei, Z. Socio-economic inequalities in health among older adults in China. Public Health 2023, 214, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboderin, I. Understanding and advancing the health of older populations in sub-Saharan Africa: Policy perspectives and evidence needs. Public Health Rev. 2010, 32, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunna, R.; San Sebastian, M.; Stewart Williams, J. Measurement and decomposition of socioeconomic inequality in single and multimorbidity in older adults in China and Ghana: Results from the WHO study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuxi, L.; Ingviya, T.; Sangthong, R.; Wan, C. Determinants of subjective well-being among migrant and local elderly in China: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawachi, I.; Subramanian, S.V.; Almeida-Filho, N. A glossary for health inequalities. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2002, 56, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorova, I.L.; Tucker, K.L.; Jimenez, M.P.; Lincoln, A.K.; Arevalo, S.; Falcón, L.M. Determinants of self-rated health and the role of acculturation: Implications for health inequalities. Ethn. Health 2013, 18, 563–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataguba, J.E.; Akazili, J.; McIntyre, D. Socioeconomic-related health inequality in South Africa: Evidence from General Household Surveys. Int. J. Equity Health 2011, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, R.; Christian, C. Access to health care in post-apartheid South Africa: Availability, affordability, acceptability. Health Econ. Policy Law 2020, 15, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szreter, S.; Woolcock, M. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 33, 650–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.-L.; Forder, J.; Trukeschitz, B.; Rokosová, M.; McDaid, D.; World Health Organization. How Can European States Design Efficient, Equitable and Sustainable Funding Systems for Long-Term Care for Older People? Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/107942 (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Olivares-Tirado, P.; Zanga Pizarro, R. Socioeconomic inequalities in functional health in older adults. J. Popul. Ageing 2023, 16, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debesay, J.; Nortvedt, L.; Langhammer, B. Social Inequalities and health among older immigrant women in the nordic Countries: An integrative review. SAGE Open Nurs. 2022, 8, 23779608221084962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlin, N.J.; Weil, J.; Felmban, W. Aging in Saudi Arabia: An exploratory study of contemporary older persons’ views about daily life, health, and the experience of aging. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2016, 2, 2333721415623911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khraif, R.M.; Salam, A.A.; Elsegaey, I.; AlMutairi, A. Changing age structures and ageing scenario of the Arab world. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 121, 763–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, P.C. Ageing and age-structural transition in the Arab countries: Regional variations, socioeconomic consequences and social security. Genus 2008, 64, 37–74. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K.; Alsharqi, O.; Almazrou, S.; Vaidya, K. Healthcare finance in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study of householders’ attitudes. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2018, 16, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K.; Alsharqi, O.; Vaidya, K. Willingness to pay for improved public health care services in Saudi Arabia: A contingent valuation study among heads of Saudi households. Health Econ. Policy Law 2020, 15, 72–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K.; Keetile, M. Socio-economic and demographic correlates of non-communicable disease risk factors among adults in Saudi Arabia. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 605912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, S.A.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Alabduljabbar, K.A.; Aldaghri, A.A.; Alhusainy, Y.A.; Khan, M.A.; Alshuwaier, R.A.; Kariz, I.N. The burden perceived by informal caregivers of the elderly in Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2017, 24, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, C.; Ayedi, Y.; Etindele Sosso, F.A. Determinants of Health Inequalities in Iran and Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review of the Sleep Literature. Clocks Sleep 2023, 5, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K.; Chirwa, G.C.; Pulok, M.H. Socio-economic inequalities in diabetes prevalence in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2020, 35, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyaemni, A.; Theobald, S.; Faragher, B.; Jehan, K.; Tolhurst, R. Gender inequities in health: An exploratory qualitative study of Saudi women’s perceptions. Women Health 2013, 53, 741–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahab, D.A.; Bamashmous, M.S.; Ranauta, A.; Muirhead, V. Socioeconomic inequalities in the utilization of dental services among adults in Saudi Arabia. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GASTAT. The General Authority for Statistics: Family Health Survey. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/965 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Debpuur, C.; Welaga, P.; Wak, G.; Hodgson, A. Self-reported health and functional limitations among older people in the Kassena-Nankana District, Ghana. Glob. Health Action 2010, 3, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepsen, R.; Dogisso, T.W.; Dysvik, E.; Andersen, J.R.; Natvig, G.K. A cross-sectional study of self-reported general health, lifestyle factors, and disease: The Hordaland Health Study. PeerJ 2014, 2, e609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fonta, C.L.; Nonvignon, J.; Aikins, M.; Nonvignon, J.; Aryeetey, G.C. Economic analysis of health inequality among the elderly in Ghana. J. Popul. Ageing 2020, 13, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, A.; Paci, P.; Van Doorslaer, E. On the measurement of inequalities in health. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 33, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, O.; Van Doorslaer, E.; Wagstaff, A.; Lindelow, M. Analyzing Health Equity Using Household Survey Data: A Guide to Techniques and Their Implementation; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Martinez, B.; Prieto-Flores, M.-E.; Forjaz, M.J.; Fernández-Mayoralas, G.; Rojo-Pérez, F.; Martínez-Martín, P. Self-perceived health status in older adults: Regional and sociodemographic inequalities in Spain. Rev. Saúde Pública 2012, 46, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseen, F.; Adhikari, R.; Soonthorndhada, K. Self-assessed health among Thai elderly. BMC Geriatr. 2010, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, L.M.; de Oliveira Novaes, C.; Mattos, I.E. Self-rated health (SRH) as a predictor of mortality in elderly men living in a medium-size city in Brazil. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2010, 51, e88–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K. Socioeconomic determinants and inequalities in the prevalence of non-communicable diseases in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molarius, A.; Berglund, K.; Eriksson, C.; Lambe, M.; Nordström, E.; Eriksson, H.G.; Feldman, I. Socioeconomic conditions, lifestyle factors, and self-rated health among men and women in Sweden. Eur. J. Public Health 2007, 17, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huijts, T.; Kraaykamp, G. Religious involvement, religious context, and self-assessed health in Europe. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2011, 52, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, Y.; Chiriboga, D.A.; Herrera, J.R.; Branch, L.G. Self-rating of poor health: A comparison of Cuban elders in Havana and Miami. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2009, 24, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinda, E.M.; Attermann, J.; Gerdtham, U.-G.; Enemark, U. Socio-economic inequalities in health and health service use among older adults in India: Results from the WHO Study on Global AGEing and adult health survey. Public Health 2016, 141, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fillenbaum, G.G.; Blay, S.L.; Pieper, C.F.; King, K.E.; Andreoli, S.B.; Gastal, F.L. The association of health and income in the elderly: Experience from a southern state of Brazil. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golini, N.; Egidi, V. The latent dimensions of poor self-rated health: How chronic diseases, functional and emotional dimensions interact influencing self-rated health in Italian elderly. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 128, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K. Decomposition of inequalities in out-of-pocket health expenditure burden in Saudi Arabia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 286, 114322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, M. Catastrophic health expenditures and its inequality in elderly households with chronic disease patients in China. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Wang, W.W.; Jones, K.; Li, Y. An exploratory multilevel analysis of income, income inequality and self-rated health of the elderly in China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2481–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimard, F.; Laszlo, S.; Lim, W. Health, aging and childhood socio-economic conditions in Mexico. J. Health Econ. 2010, 29, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S.; Grundy, E.; Foverskov, E. Socio-economic position and subjective health and well-being among older people in Europe: A systematic narrative review. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 20, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achdut, N.; Sarid, O. Socio-economic status, self-rated health and mental health: The mediation effect of social participation on early-late midlife and older adults. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2020, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melchiorre, M.G.; Chiatti, C.; Lamura, G.; Torres-Gonzales, F.; Stankunas, M.; Lindert, J.; Ioannidi-Kapolou, E.; Barros, H.; Macassa, G.; Soares, J.F. Social support, socio-economic status, health and abuse among older people in seven European countries. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).