Abstract

(1) Background: Few studies have examined risk factors of frailty during early life and mid-adulthood, which may be critical to prevent frailty and/or postpone it. The aim was to identify early life and adulthood risk factors associated with frailty. (2) Methods: A systematic review of cohort studies (of at least 10 years of follow-up), using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA). A risk of confounding score was created by the authors for risk of bias assessment. Three databases were searched from inception until 1 January 2023 (Web of Science, Embase, PubMed). Inclusion criteria were any cohort study that evaluated associations between any risk factor and frailty. (3) Results: Overall, a total of 5765 articles were identified, with 33 meeting the inclusion criteria. Of the included studies, only 16 were categorized as having a low risk of confounding due to pre-existing diseases. The long-term risk of frailty was lower among individuals who were normal weight, physically active, consumed fruits and vegetables regularly, and refrained from tobacco smoking, excessive alcohol intake, and regular consumption of sugar or artificially sweetened drinks. (4) Conclusions: Frailty in older adults might be prevented or postponed with behaviors related to ideal cardiovascular health.

1. Introduction

Numerous potential biomarkers of aging have been proposed in the scientific literature, including molecular, imaging, and clinical data [1]. Frailty is a composite aging biomarker characterized by a condition of decreased physiological reserve that leads to a vulnerable state and increases the risk of adverse health outcomes when exposed to a stressor [1]. In 2001, two definitions of frailty were introduced in the geriatric literature (although more definitions can be found in the scientific literature). The phenotypic model of Fried et al. [2] is based on the presence of three (or more) of the following characteristics: (a) an involuntary weight loss, (b) self-reported exhaustion in daily life activities, (c) a low level of physical activity, (d) habitual slow walking speed, and (e) muscular weakness. Another frailty definition is the accumulation of deficits model (or frailty index) of Mitnitski et al. [3], which includes deficiencies of functional, sensory, and clinical nature. In a recent systematic review, the prevalence of frailty in older adults in 62 countries and territories was 12% (Fried phenotype) or 24% (frailty index) [4]. Women and individuals of a low socioeconomic status level are more likely to become frail, according to a narrative review of Taylor et al. [5]. Frailty remains an important public health problem because frail individuals (versus non-frail) are at higher risk of physical disability [2], falls [6], fractures [7], hospitalizations [8], institutionalization [9], and death [10].

In a recent systematic review of older adults (at least 65 years old) [11], authors identified a large number of lifestyle factors and characteristics associated with frailty. Information was mainly derived from cross-sectional studies or cohort studies with a short follow-up. However, it is well established that a life-course perspective offers a more suitable approach to understanding how the aging processes and their consequences emerge during the lifetime [12]. Lowering the accumulation of harmful exposures throughout the life course or changing unhealthy behaviors during adulthood may lead to more favorable trajectories of aging [12]. However, many statistical associations found in observational studies of risk factors of frailty could reflect bias (reverse causality, selection bias, and measurement errors), confounding, or chance [13]. To reduce the risk of bias due to pre-existing diseases in the synthesis of evidence, some epidemiologists recommend following some analytical approaches [14], such as (1) excluding (or adjusting for) participants with major noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) at baseline (CVDs, stroke, cancer, and respiratory diseases); (2) including only cohort studies with a minimum of 10 years of follow-up in meta-analysis; and (3) excluding death cases occurring in the first 5 years of follow-up.

To sum up, to the best of our knowledge, no systematic review until now has evaluated how early-life and middle-life risk factors are associated with frailty or studied their epidemiological validity using risk of bias assessments. The main objective of this systematic review was to identify early- and middle-life risk factors associated with frailty in older adults. We also aimed to examine whether authors included appropriate analytical methods to deal with confounding due to pre-existing diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search and Screening

To formulate a clear and concise research question, a description of the population, intervention/exposure, comparison, and outcomes are provided. We searched cohort studies that examined associations between any risk factor (Exposure) during adulthood, adolescence, childhood, or natal factors (Population) associated with frailty (Outcome), using Web of Science, Embase, and PubMed (from inception until 1 January 2023). One researcher (A.S.) was in charge of producing the first database for the identification of relevant scientific literature. Details of the list of keywords are included in Table S1. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines to report the results of this systematic review [15]. Two authors, A.B. and J.P.R.-L., screened independently articles by title and abstract and, in a later stage, reading full-text articles using the website covidence.org In case of discrepancies, a third author (C.J.K.) made a final decision.

The eligibility criteria of this systematic review were any cohort study in humans (both sexes, healthy at baseline), published in English language, that evaluated associations of risk factors associated with frailty status in humans. Studies with a retrospective study design were eligible studies, as they inform about early-in-life risk factors. In addition, we considered eligible those studies cited in references from selected studies. Exclusion criteria: studies whose cohort studies had a follow-up lower than 10 years were excluded because they did not inform of early- or middle-life risk factors. Studies published in non-English language or abstracts of conferences were excluded.

2.2. Data Extraction

We retrieved the first author’s name, year of publication, country, sample size, participant’s sex, age at baseline, exposure variable/s, frailty definition, average length of follow-up, and fully adjusted hazard ratio (HR) or odds ratio (OR) or relative risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for frailty, comparing for each exposure variable (using 1-unit increase or comparations between categories with the highest and lowest values; Comparison). We also extracted data about the covariates used in the fully adjusted model and whether authors included sensitivity analyses in their publications. Data extraction was performed by one researcher (A.B.) and double-checked by another (J.P.R.-L.).

2.3. Risk of Confounding Due to Pre-Existing Diseases

Three methodological characteristics defined the risk of confounding based on subject matter expertise instead of a mechanistic risk of bias assessment [16]: average age at baseline of 70+ years, authors did not exclude participants with diseases/conditions at baseline and did not adjust for diseases/conditions in the fully adjusted model. A risk of confounding score was created with the three mentioned characteristics (ranging from zero to three). We defined a high risk of confounding due to pre-existing diseases when studies had two or three points in the confounding score (total of three). Scores were calculated by one senior researcher (J.P.R.-L.) with prior experience in risk-of-bias assessments of epidemiological studies. A comprehensive meta-analysis of each risk factor identified was initially planned, taking into account the risk of confounding scores, but it was finally discarded due to the scarce number of studies identified.

3. Results

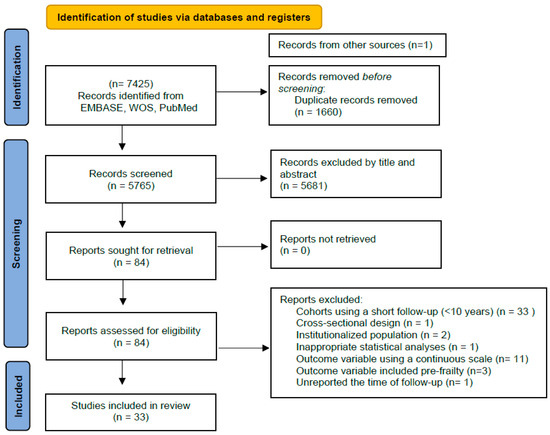

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram used in the present systematic review. A total of 7425 records were initially identified. After screening 5681 articles by title and abstract, 84 articles were retrieved for eligibility analyses through a full-text reading. Of these, 33 articles were finally selected [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Each section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram showing 33 cohort studies (with at least 10 years of follow-up) of early-life and middle-life risk factors of frailty.

Table 1 describes the main characteristics of all cohort studies selected. The population sample sizes ranged between 323 and 121,700 participants; 24 studies were conducted on both sexes, 4 only in men, and 5 only in women; 8 studies recruited participants in the USA, 7 in Finland, 1 in Australia, 4 in France, 6 in the United Kingdon, 1 in Israel, 1 in Sweden, 3 from China, and 1 in the Netherlands; participants were followed up between 10 and 30 years; the 11 definitions of frailty used across the cohort studies were Fried phenotype [2] (15 studies), Modified Fried phenotype (6 studies), FRAIL scale—Abellan van Kan et al. [50] (1 study), FRAIL scale—Morley et al. [51] (4 studies), Modified FRAIL scale—Morley et al. (1 study), Frailty index—Mitnitski et al. [3] (2 studies), Hospital Frailty Risk Score (HFRS)—Gilbert et al. [52] (1 study), Frailty phenotype—Kucharska-Newton et al. [53] (1 study), Frailty phenotype—Strawbridge et al. [54] (1 study), and Frailty index—Searle et al. [55] (1 study). The prevalence of frailty ranged between 2 and 61%.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of 33 cohort studies included, examining associations between any exposure variable and risk of frailty.

The exposure variables of the 33 articles selected were dietary inflammatory index in adulthood (1 study), blood inflammatory markers in adulthood (two studies), alcohol consumption in adulthood (three studies), sitting time in adulthood (one study), multicomponent healthy heart score in adulthood (one study), overweight/obesity or higher BMI in adulthood (four studies), neighborhood-social deprivation in childhood (one study), cardiovascular risk scores in adulthood (two studies), physical inactivity in adulthood (five studies), asthma in adulthood (one study), anemia in adulthood (one study), diabetes in adulthood (one study), high liver enzymes (one study), dietary clusters (pasta or biscuits plus snacking) in adulthood (one study), birth body composition (BMI, weight, length) (one study), children of separated parents in childhood (one study), fruit and vegetable consumption in adulthood (three studies), smoking status in adulthood (two studies), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) use (one study), neighborhood quality in adulthood (one study), education level achievement (three studies), paternal education (one study), occupation or employment level in adulthood (two studies), low literacy in adulthood (one study), low income in adulthood (one study), malnutrition in adulthood (one study), depression in adulthood (one study), forced expiratory volume or HDL cholesterol or hypertension (one study), sugar-sweetened beverages or artificial sweetened beverage or orange juices or non-orange juices (one study), red meat in adulthood (one study), pain during walking in adulthood (one study), subjective social status (one study), health-related quality of life (one study), and social vulnerability index in adulthood (one study).

Table 2 shows the analytical approaches used to account for confounding due to pre-existing diseases in 33 studies examining the association between risk factors and frailty. In 10 of them, authors omitted the inclusion of any type of disease as a covariate in their fully adjusted models; only 2 studies excluded all participants with diseases in main analyses; and another 2 used sensitivity analyses.

Table 2.

Analytical approaches to account for confounding due to pre-existing diseases in 33 studies of risk factors and frailty.

Table 3 shows the scored risk of confounding due to pre-existing diseases in the 33 studies selected. The final score takes into account whether studies included participants younger than 70 years at baseline or not, whether studies excluded participants with diseases/conditions at baseline, and whether studies adjusted for diseases/conditions in the fully adjusted model. A total of 16 studies scored a low risk of confounding due to pre-existing diseases (0 or 1 point) and the rest a high risk of confounding (2 or 3 points).

Table 3.

Score risk of confounding due to pre-existing diseases in 33 studies examining the association between risk factors and frailty.

Table S2 shows whether authors included physical activity or nutritional factors (energy intake, quality nutritional indexes, sugar-sweetened beverages, and red meat) as covariates in their regression models. In 20 studies, authors omitted both physical activity and nutritional factors as covariates in their statistical analyses.

4. Discussion

The goal of this systematic review was to identify early-life and middle-life risk factors (any exposure variable) associated with frailty. We found evidence that maintaining a normal weight in adulthood, being physically active, not smoking tobacco, refraining from ultra-processed food and beverages, and avoiding excessive alcohol intake may decrease the risk of frailty several decades later. These findings may have important implications for elderly populations because, in theory, most cases of frailty might be prevented if populations remain healthy before older age. For example, staying physically active in adulthood was robustly associated with a lower future risk of frailty [32]. The physiological mechanisms underlying the positive influence of physical activity on frailty prevention have been comprehensively reviewed elsewhere [5]. On the other hand, the regular consumption of fruits and vegetables and a low consumption of SSBs or ASBs were also associated with a lower risk of becoming frail [46]. Therefore, it seems unquestionable that diet and physical activity have a key role in preventing the future risk of frailty. In support of this, we found that obesity [21], diabetes [26], or having worse cardiovascular risk scores [27] or blood inflammatory markers [40] were equally associated with a higher risk of frailty. The mechanisms by which high ultra-processed foods and beverages promote obesity, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease are complex and only partially known nowadays. High ultra-processed foods and beverages may result in unique patterns of gut–brain signals during digestion processes, as they are absorbed more proximally in the gut compared with natural foods and beverages. Altered absorption of nutrients and a low amount of fiber in the diet may play important disruptions in appetite control, leading to a long-term positive energy balance [56].

Nonetheless, a second goal of our review was to evaluate whether authors included appropriate analytical methods to deal with confounding due to pre-existing diseases and we found serious deficiencies in this matter. For example, many (half of the studies selected) epidemiological studies of risk factors of frailty were at high risk of confounding due to pre-existing diseases. Another source of concern was the observation that the majority of studies did not adjust their effect estimates by important confounders such as physical activity or nutritional factors. The framing that frailty is a direct consequence of the normal aging process should be approached with caution, as we also find evidence that frailty was associated with worse socioeconomic markers (income, education, and employment). So far, the mechanisms linking socioeconomic factors with frailty remain unexplored, and multiple factors may be involved (beyond the proven benefits of physical activity or healthy diets). Although the best way to define frailty is still debated among scientists [51], future studies should adopt (at least) the most common definition of frailty (Fried phenotype) to allow a future synthesis of the scientific evidence [57].

To move the field forward, it is important to acknowledge that well-powered randomized clinical trials, although the gold standard of scientific inquiry, are limited in their ability to add valuable insights for prevention because it is unfeasible to test human interventions with a duration of 10 years or more. To illustrate how clinical trials in the elderly do not always offer important insights about how to prevent frailty, see reference [58], where a complex intervention that combined a nutrition plus physical activity intervention over 2 years was ineffective in reducing frailty in older adults. Although it could be argued that the design of interventions was not optimal (for example, short duration or the physical activity intervention only included 1 h per week of strength plus balance instead of exercise programs of aerobic activities based on physical activity recommendations for health in adults), the authors stressed that their interventions mirrored the real world (good external validity). Consequently, we think that future studies on this topic should rely on well-designed cohort studies with valid methodologies of assessment of exposure variables and robust statistical analysis (including sensitivity analyses). Our systematic review examines, for the first time, what modifiable factors may determine a higher long-term risk of frailty (life course epidemiology) and evaluates the risk of confounding due to pre-existing diseases. Despite employing a comprehensive search strategy, we found very few studies evaluating the same exposure variable, which precluded our ability to perform additional meta-analyses. Therefore, we acknowledge that progress in this field of study is still limited. Nonetheless, facilitating the adoption of cardiovascular healthy behaviors in the general population seems a promising strategy of intervention to prevent frailty.

5. Conclusions

Maintaining a normal weight in adulthood, being physically active, not smoking tobacco, refraining from ultra-processed food and beverages, and avoiding excessive alcohol intake may decrease the risk of frailty several decades later. The framing that frailty is a direct consequence of the normal aging process should be viewed with caution, as we found clear evidence that more vulnerable socioeconomic groups are more likely to become frail.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare12010022/s1, Table S1: Search strategy of the systematic review of cohort studies examining associations of risk factors with frailty; Table S2: Physical activity and nutritional variables as covariates in 33 studies examining the association between risk factors and frailty.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.R.-L.; methodology, J.P.R.-L. and L.F.M.R.; software, A.S.; data extraction, J.P.R.-L. and A.B.; writing and editing, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this systematic review. Readers may contact with corresponding author to clarify any doubt regarding the methodology used.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Bulloch, G.; Zhang, J.; Liao, H.; Shang, X.; Clark, M.; Peng, Q.; Ge, Z.; et al. Biomarkers of ageing: Current state-of-art, challenges, and opportunities. MedComm-Future Med. 2023, 2, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitnitski, A.B.; Mogilner, A.J.; Rockwood, K. Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. Sci. World J. 2001, 1, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Caoimj, R.; Sezgin, D.; O’Donovan, M.R.; William Molloy, D.; Clegg, A.; Rockwood, M.R.; Liew, A. Prevalence of frailty in 62 countries across the world: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population-level studies. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.A.; Greenhaff, P.L.; Bartlett, D.B.; Jackson, T.A.; Duggal, N.A.; Lord, J.M. A multisystem physiological perspective of human frailty and its modulation by physical activity. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103, 1137–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, G. Frailty as a predictor of future falls among community-dwelling older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensrud, K.E.; Ewing, S.K.; Taylor, B.C.; Fink, H.A.; Stone, K.L.; Cauley, J.A.; Tracy, J.K.; Hochberg, M.C.; Rodondi, N.; Cawthon, P.M.; et al. Frailty and risk of falls, fracture, and mortality in older women: The study of osteoporotic fractures. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2007, 62, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, G. Frailty as a predictor of hospitalization among community-dwelling older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, G. Frailty as a predictor of nursing home placement among community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2018, 41, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamliyan, T.; Talley, K.M.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Kane, R.L. Association of frailty with survival: A systematic literature review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2013, 12, 719–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hu, J.; Wu, D. Risk factors for frailty in older adults. Medicine 2022, 101, e30169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shultz, J.M.; Sullivan, L.M.; Galea, S. Public Health: An Introduction to the Science and Practice of Population Health, 1st ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 182–185. [Google Scholar]

- Hernan, M.A.; Robins, J.M. Causal Inference: What If? Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rezende, L.F.M.; Lee, D.H.; Ferrari, G.; Giovannucci, E. Confounding due to pre-existing diseases in epidemiological studies on sedentary behavior and all-cause mortality: A meta-epidemiological study. Ann. Epidemiol. 2020, 52, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savitz, D.A.; Wellenius, G.A.; Trikalinos, T.A. The problem with mechanistic risk of bias assessments in evidence synthesis of observational studies and a practical alternative: Assessing the impact of specific sources of potential bias. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 1581e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millar, C.L.; Dufour, A.B.; Shivappa, N.; Habtemariam, D.; Murabito, J.M.; Benjamin, E.J.; Hebert, J.R.; Kiel, D.P.; Hannan, M.T.; Sahni, S. A proinflammatory diet is associated with increased odds of frailty after 12-year follow-up in a cohort of adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strandberg, A.Y.; Trygg, T.; Pitkälä, K.H.; Strandberg, T.E. Alcohol consumption in midlife and old age and risk of frailty: Alcohol paradox in a 30-year follow-up study. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susanto, M.; Hubbard, R.E.; Gardiner, P.A. Association of 12-year trajectories of sitting time with frailty in middle-aged women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 187, 2387–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotos-Prieto, M.; Struijk, E.A.; Fung, T.T.; Rimm, E.B.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B.; Lopez-Garcia, E. Association between a lifestyle-based healthy heart score and risk of frailty in older women: A cohort study. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afab268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landré, B.; Czernichow, S.; Goldberg, M.; Zins, M.; Ankri, J.; Herr, M. Association between life-course obesity and frailty in older adults: Findings in the GAZEL cohort. Obesity 2020, 28, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranyi, G.; Welstead, M.; Corley, J.; Deary, I.J.; Muniz-Terrera, G.; Redmond, P.; Shortt, N.; Taylor, A.M.; Ward Thompson, C.; Cox, S.R.; et al. Association of life-course neighborhood deprivation with frailty and frailty progression from ages 70 to 82 years in the Lothian birth cohort 1936. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 191, 1856–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandberg, T.E.; Sirola, J.; Pitkälä, K.H.; Tilvis, R.S.; Strandberg, A.Y.; Stenholm, S. Association of midlife obesity and cardiovascular risk with old age frailty: A 26-year follow-up of initially healthy men. Int. J. Obes. 2012, 36, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheifets, M.; Goshen, A.; Goldbourt, U.; Witberg, G.; Eisen, A.; Kornowski, R.; Gerber, Y. Association of socioeconomic status measures with physical activity and subsequent frailty in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landré, B.; Nadif, R.; Goldberg, M.; Gourmelen, J.; Zins, M.; Ankri, J.; Herr, M. Asthma is associated with frailty among community-dwelling adults: The GAZEL cohort. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2020, 7, e000526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, A.M.; Ding, M.; Ebeling, M.; Hammar, N.; Modig, K. Blood-based biomarkers and long-term risk of frailty-experience from the Swedish AMORIS cohort. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2021, 76, 1643–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, K.; Batty, G.D.; Hamer, M.; Sabia, S.; Shipley, M.J.; Britton, A.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Kivimäki, M. Cardiovascular disease risk scores in identifying future frailty: The Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Heart 2013, 99, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilleron, S.; Ajana, S.; Jutand, M.A.; Helmer, C.; Dartigues, J.F.; Samieri, C.; Féart, C. Dietary patterns and 12-year risk of frailty: Results from the three-city Bordeaux study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haapanen, M.J.; Perälä, M.M.; Salonen, M.K.; Kajantie, E.; Simonen, M.; Pohjolainen, P.; Eriksson, J.G.; von Bonsdorff, M.B. Early life determinants of frailty in old age: The Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haapanen, M.J.; Perälä, M.M.; Salonen, M.K.; Kajantie, E.; Simonen, M.; Pohjolainen, P.; Pesonen, A.K.; Räikkönen, K.; Eriksson, J.G.; von Bonsdorff, M.B. Early life stress and frailty in old age: The Helsinki birth cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, T.T.; Struijk, E.A.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Willett, W.C.; Lopez-Garcia, E. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of frailty in women 60 years old or older. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 1540–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Salcedo, A.; Dugravot, A.; Fayosse, A.; Dumurgier, J.; Bouillon, K.; Schnitzler, A.; Kivimäki, M.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Sabia, S. Healthy behaviors at age 50 years and frailty at older ages in a 20-year follow-up of the UK Whitehall II cohort: A longitudinal study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haapanen, M.J.; Perälä, M.M.; Osmond, C.; Salonen, M.K.; Kajantie, E.; Rantanen, T.; Simonen, M.; Pohjolainen, P.; Eriksson, J.G.; von Bonsdorff, M.B. Infant and childhood growth and frailty in old age: The Helsinki birth cohort study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 31, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkaby, A.R.; Ward, R.; Chen, J.; Shanbhag, A.; Sesso, H.D.; Gaziano, J.M.; Djousse, L.; Driver, J.A. Influence of long-term nonaspirin NSAID use on risk of frailty in men ≥60 years: The Physicians’ Health study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2022, 77, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savela, S.L.; Koistinen, P.; Stenholm, S.; Tilvis, R.S.; Strandberg, A.Y.; Pitkälä, K.H.; Salomaa, V.V.; Strandberg, T.E. Leisure-time physical activity in midlife is related to old age frailty. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 1433–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xue, Q.L.; Odden, M.C.; Chen, X.; Wu, C. Linking early life risk factors to frailty in old age: Evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.S.Y.; Chan, R.S.M.; Kwok, T.; Lee, J.S.W.; Woo, J. Malnutrition according to GLIM criteria and adverse outcomes in community-dwelling Chinese older adults: A prospective analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 1953–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, E.J.; Shipley, M.J.; Ahmadi-Abhari, S.; Valencia Hernandez, C.; Abell, J.G.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Kawachi, I.; Kivimaki, M. Midlife contributors to socioeconomic differences in frailty during later life: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2018, 3, e313–e322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenholm, S.; Strandberg, T.E.; Pitkälä, K.; Sainio, P.; Heliövaara, M.; Koskinen, S. Midlife obesity and risk of frailty in old age during a 22-year follow-up in men and women: The mini-Finland follow-up survey. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.A.; Walston, J.; Gottesman, R.F.; Kucharska-Newton, A.; Palta, P.; Windham, B.G. Midlife systemic inflammation is associated with frailty in later life: The ARIC Study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2019, 74, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, J.K.; Karmarkar, A.; Raji, M.; Markides, K.S.; Ottenbacher, K.J.; Al Snih, S. Pain as a predictor of frailty over time among older Mexican Americans. Pain 2020, 161, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struijk, E.A.; Fung, T.T.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B.; Lopez-Garcia, E. Red meat consumption and risk of frailty in older women. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugravot, A.; Fayosse, A.; Dumurgier, J.; Bouillon, K.; Rayana, T.B.; Schnitzler, A.; Kivimaki, M.; Sabia, S.; Singh-Manoux, A. Social inequalities in multimorbidity, frailty, disability, and transitions to mortality: A 24-year follow-up of the Whitehall II cohort study. Lancet Public. Health 2020, 5, e42–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendijk, E.O.; Heymans, M.W.; Deeg, D.J.H.; Huisman, M. Socioeconomic inequalities in frailty among older adults: Results from a 10-year longitudinal study in the Netherlands. Gerontology 2018, 64, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Tong, C.; Leung, J.; Woo, J. Socioeconomic inequalities in frailty in Hong Kong, China: A 14-year longitudinal cohort study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struijk, E.A.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Fung, T.T.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B.; Lopez-Garcia, E. Sweetened beverages and risk of frailty among older women in the Nurses’ Health Study: A cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landré, B.; Ben Hassen, C.; Kivimaki, M.; Bloomberg, M.; Dugravot, A.; Schniztler, A.; Sabia, S.; Singh-Manoux, A. Trajectories of physical and mental functioning over 25 years before onset of frailty: Results from the Whitehall II cohort study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amieva, H.; Ouvrard-Brouillou, C.; Dartigues, J.F.; Pérès, K.; Tabue Teguo, M.; Avila-Funes, A. Social vulnerability predicts frailty: Towards a distinction between fragility and frailty? J. Frailty Aging 2022, 11, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederstrasser, N.G.; Rogers, N.T.; Bandelow, S. Determinants of frailty development and progression using a multidimensional frailty index: Evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellan van Kan, G.; Rolland, Y.; Bergman, H.; The, I.A.N.A. Task Force on frailty assessment of older people in clinical practice. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2008, 12, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, J.E.; Malmstrom, T.K.; Miller, D.K. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2012, 16, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, T.; Neuburger, J.; Kraindler, J.; Keeble, E.; Smith, P.; Ariti, C. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: An observational study. Lancet 2018, 391, 1775–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska-Newton, A.M.; Palta, P.; Burgard, S.; Griswold, M.E.; Lund, J.L.; Capistrant, B.D.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Windham, B.G. Operationalizing frailty in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study Cohort. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2017, 72, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strawbridge, W.J.; Shema, S.J.; Balfour, J.L.; Higby, H.R.; Kaplan, G.A. Antecedents of frailty over three decades in an older cohort. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 1998, 53, S9–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Searle, S.D.; Mitnitski, A.; Gahbauer, E.A.; Gill, T.M.; Rockwood, K. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr 2008, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, K.D. From dearth to excess: The rise of obesity in an ultra-processed food system. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 378, 20220214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendijk, E.O.; Afilalo, J.; Ensrud, K.E.; Kowal, P.; Onder, G.; Fried, L.P. Frailty: Implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet 2019, 394, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, R.; Barnett, D.; Edlin, R.; Kerse, N.; Waters, D.L.; Hale, L.; Tay, E.; Leilua, E.; Pillai, A. Effectiveness of a complex intervention of group based nutrition and physical activity to prevent frailty in pre-frail older adults (SUPER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022, 3, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).