Long-Term Care Research in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Bibliometric Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. CiteSpace

2.2. Bibliographic Records

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Global Publication Outputs

- -

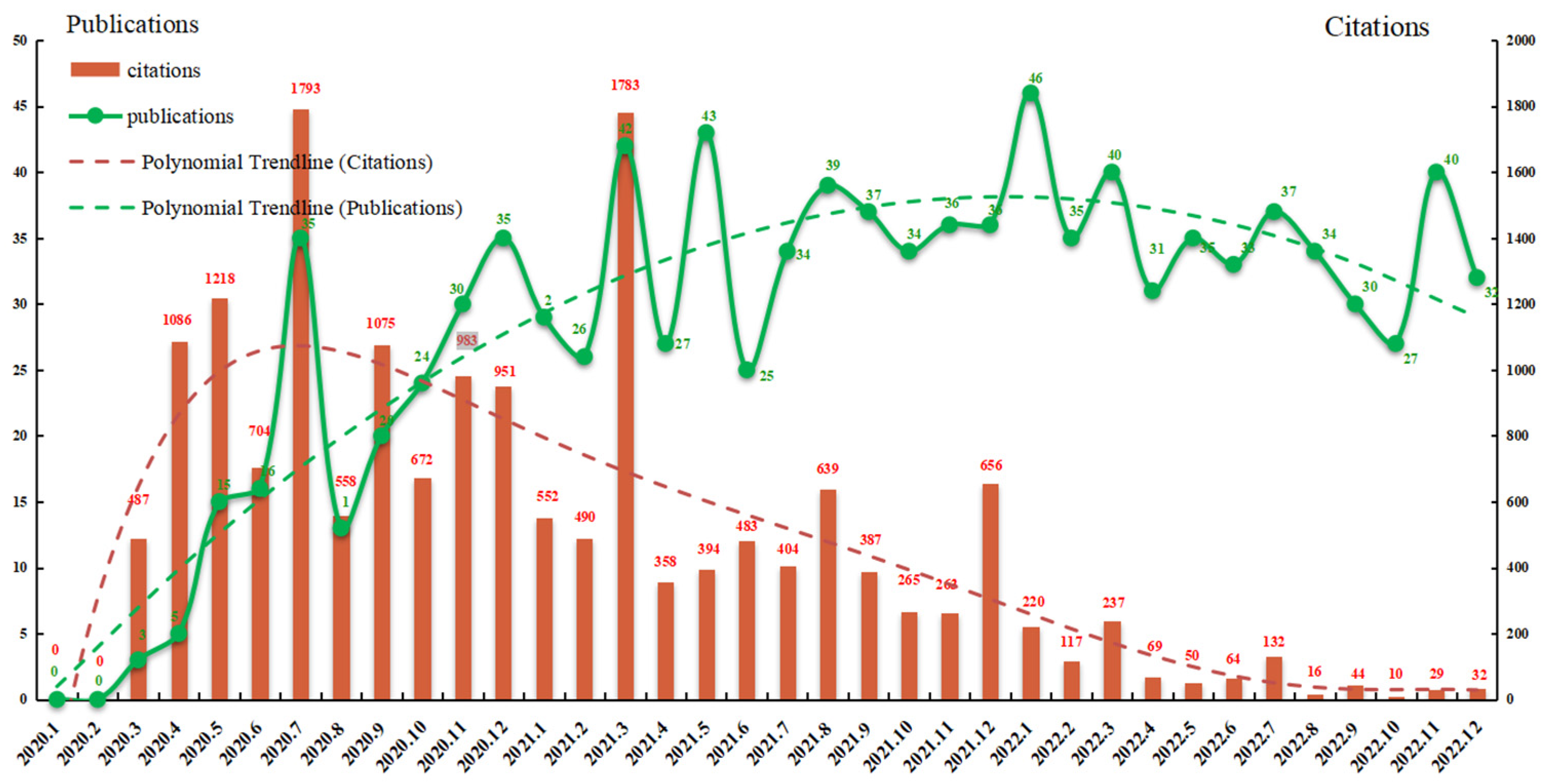

- Preparation phase (January 2020–June 2020). At the beginning of this stage, no relevant article was published in January and February. Despite the huge impact of COVID-19 on LTC, little literature had been published at this stage, probably because the relative impact of COVID-19 on LTC research was still in the exploratory stage. Remarkably, although only a few articles were published in March, April, and May in 2020, these articles had a high number of citations, which proved their influence in the LTC research field. It also revealed that there was a strong accumulation of citations, and the earlier the papers published, the higher the citations.

- -

- Fluctuating growth phase (July 2020–June 2021). The number of publications maintained a trend of continuous fluctuating growth during this period, and reached the peak in December 2020, March 2021, and May 2021, respectively. The number of articles increased more rapidly than before, and more than 345 articles were published. It is worth noting that the biggest citation burst was found in July 2020 (1793) and March 2021 (1783), and the number of citations exceeded 500 in most months in this period, indicating that scholars had paid great attention to LTC research and produced many high-quality papers.

- -

- Stable development phase (July 2021–December 2022). Since July 2021, LTC research in the context of the pandemic had become one of the most significant concerns among policy makers, related scientists, international organizations, and national organizations. The number of publications remained at a high level, with an average of more than 30, but fluctuated slightly. In consideration of the citation trendline, the number of citations of the papers continued to decline. Such a decrease can be explained by taking into account that citations of newly published articles are subject to the time lag and have less chance of being cited.

3.2. Collaboration Network Analysis

3.2.1. Network of Countries/Regions

3.2.2. Network of Institutions

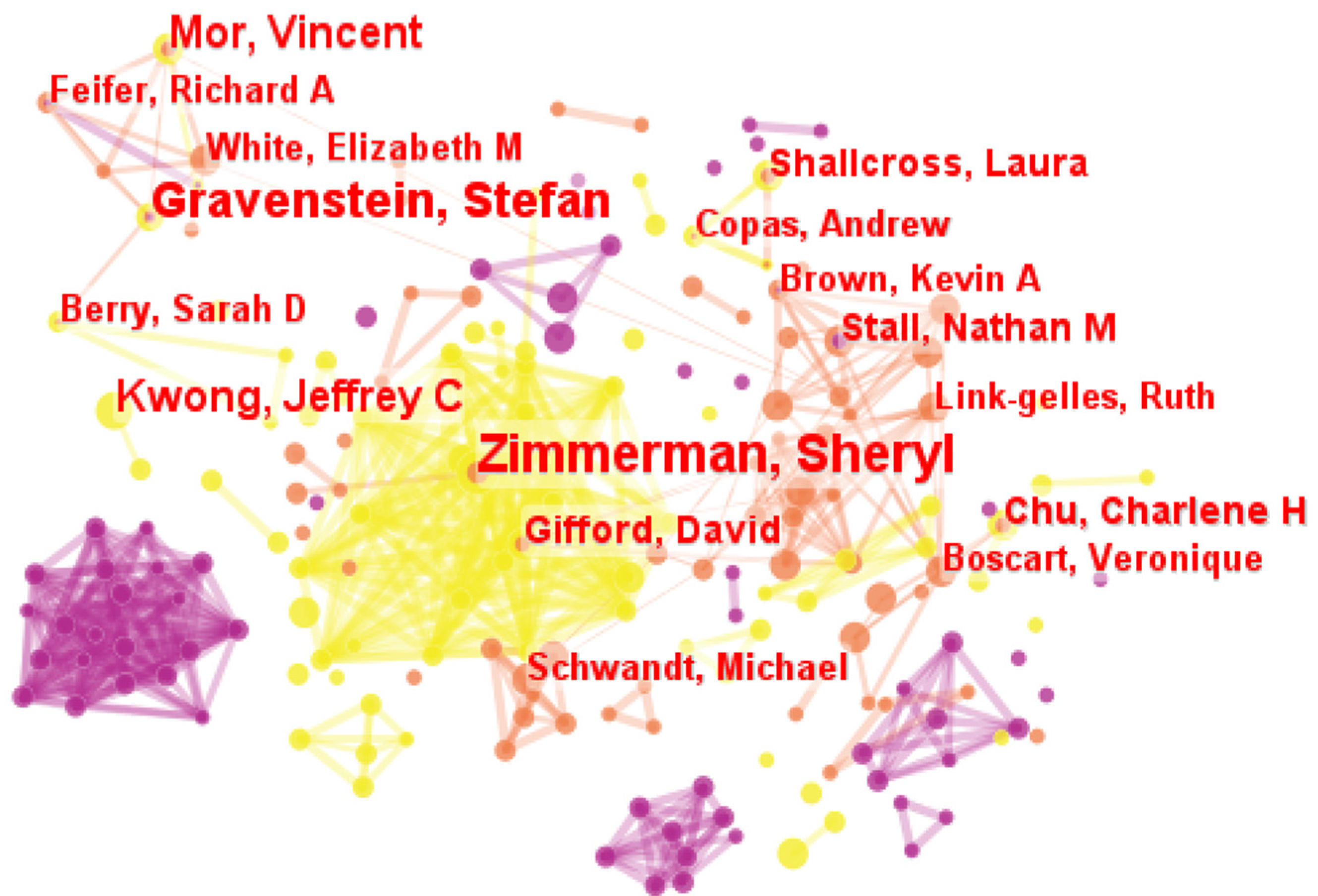

3.2.3. Network of Authors

3.3. Document Co-Citation and Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis of LTC Field in the Pandemic

3.3.1. Document Co-Citation Network

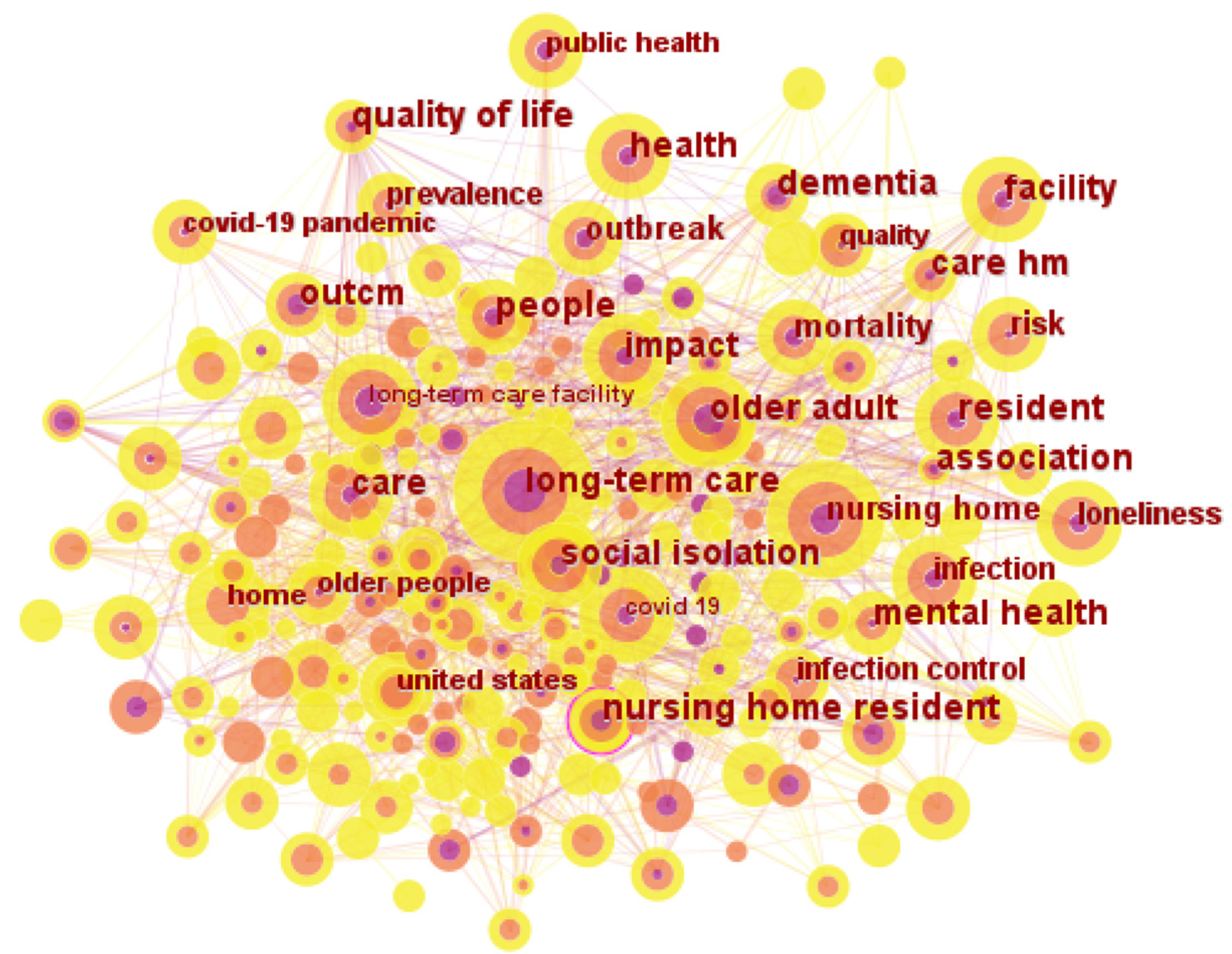

3.3.2. Keyword Co-Occurrence Network

- -

- Nursing homes and residents was extracted using keywords “nursing home”, “long-term care”, “long-term care facility”, “resident”, “impact”, “facility”, “United States”, and “nursing home residents”. At the first outbreak of COVID-19, nursing homes became the hotbed for it [6]. According to the data, more than one-third of COVID-19 death happened at nursing homes in the United States, even in some states, the proportion is more than one-half [54]. Viral infection and COVID-19 disease are prevalent among nursing home residents [29], due to their congregant living environments, greater likelihood of being exposed to asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic care providers, and difficulty in effectively implementing infection prevention and control practices [22]. This pandemic had put both nursing homes and residents at acute risk highlighting the limited resources many facilities had in dealing with crises of this magnitude [29].

- -

- Older people in need of LTC in the pandemic was identified using nine keywords “long-term care”, “older adult”, “COVID-19”, “care”, “health”, “infection”, “risk”, “older people”, “mortality”, “dementia”, and “mental health”. Older people were the group of most susceptible to COVID-19, adding further difficulties to their LTC [25,45,46]. This was mainly due to the higher incidence of immune dysfunction, chronic diseases, and disabilities in the elderly, which could develop a more severe form of the disease, and further lead to increasing mortality [22,25]. Furthermore, as for the individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia, the pandemic disrupted not only the basic routines, but also the LTC that promote their physical and mental health [12]. However, it is particularly distressing that few care to frail and needy older people could be offered [46]. Awareness of clinical differences of COVID-19 in this population, quickly initiating appropriate behaviors to care for the infected, and preventive interventions would help better LTC for the elderly in this crisis [25].

- -

- Infection prevention and control strategies was extracted using the keywords “COVID-19”, “infection”, “outbreak”, “prevalence”, and “public health”. There was a consensus that all patients involved in LTC should take proactive steps to prevent the epidemic [20,22]. To begin with, for residents of LTC facilities, frequent hand washing, universal use of face masks, and reducing contact were effective ways to control the spread of the epidemic [22,58,59]. For all facilities providing LTC, strategies include restricting nonessential personnel from entering the facility [20,22]; additional prevention measures for asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic [30,54]; increasing in payments to direct caregivers [29]; and continuous communication with residents and family members [12,45]. Government departments and national health departments might need to enhance the infection control capacity [12], invest in public health infrastructure [29], improve international surveillance, cooperation, coordination, and communication, as well as be better prepared to respond to future new public health threats [33].

- -

- Social isolation and loneliness comprised eight representative keywords “COVID-19”, “infection”, “risk”, “quality”, “social isolation”, “loneliness”, “mental health”, and “home”. Social isolation and loneliness caused by quarantine policies adopted to prevent the spread of the epidemic take a serious toll on the physical and mental health of older people in need of LTC [34,49]. Personal interactions were meaningful activities and are crucial to improve the quality of LTC [30]. Many older people in need of LTC were socially isolated and lonely, depending on frequent visits from family and friends to socialize with them [34]. However, quarantine policies during the pandemic prevented these visits, making older people feel increasingly lonely, abandoned, and despondent [34]. At the same time, it could also cause anxiety and emotional trauma to families and others who could not visit their loved ones [29]. Therefore, it is important to recognize the role that family members play as partners in LTC of the elderly and develop visitor policies in LTC facilities during the pandemic [30].

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- COVID-19 Confirmed Cases and Deaths Age- and Sex-Disaggregated Data. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/covid-19-confirmed-cases-and-deaths-dashboard/ (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- CDC. Confirmed COVID-19 Cases among Residents and Rate per 1000 Resident-Weeks in Nursing Homes, by Week—United States. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/covid19/ltc-report-overview.html (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Long-Term-Care COVID Tracker. Available online: https://covidtracking.com/nursing-homes-long-term-care-facilities (accessed on 6 November 2022).

- Fu, L.; Sun, Z.; He, L.; Liu, F.; Jing, X. Global long-term care research: A scientometric review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.C.; Barbu, M.G.; Beiu, C.; Popa, L.G.; Mihai, M.M.; Berteanu, M.; Popescu, M.N. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on long-term care facilities worldwide: An overview on international issues. J. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 8870249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konetzka, R.T.; White, E.M.; Pralea, A.; Grabowski, D.C.; Mor, V. A systematic review of long-term care facility characteristics associated with COVID-19 outcomes. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 2766–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Chen, C.; Dong, X.P. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with neurodegenerative diseases. J. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 664965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.M.; Dubin, R.; Kim, M.C. Orphan drugs and rare diseases: A scientometric review (2000–2014). Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2014, 2, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.M. CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2006, 57, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloane, P.D.; Yearby, R.; Konetzka, R.T.; Li, Y.; Espinoza, R.; Zimmerman, S. Addressing systemic racism in nursing homes: A time for action. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, S.; Dumond-Stryker, C.; Tandan, M.; Preisser, J.S.; Wretman, C.J.; Howell, A.; Ryan, S. Nontraditional small house nursing homes have fewer COVID-19 cases and deaths. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vipperman, A.; Zimmerman, S.; Sloane, P.D. COVID-19 recommendations for assisted living: Implications for the future. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 933–938.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurwitz, J.H.; Quinn, C.C.; Abi-Elias, I.H.; Adams, A.S.; Bartel, R.; Bonner, A.; Boxer, R.; Delude, C.; Gifford, D.; Hanson, B.; et al. Advancing clinical trials in nursing homes: A proposed roadmap to success. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.M.; Kosar, C.M.; Feifer, R.A.; Blackman, C.; Gravenstein, S.; Ouslander, J.; Mor, V. Variation in SARS-CoV-2 prevalence in US skilled nursing facilities. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2167–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lally, M.A.; Tsoukas, P.; Halladay, C.W.; O’Neill, E.; Gravenstein, S.; Rudolph, J.L. Metformin is associated with decreased 30-day mortality among nursing home residents infected with SARS-CoV-2. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, V.; Gutman, R.; Yang, X.; White, E.M.; McConeghy, K.W.; Feifer, R.A.; Blackman, C.R.; Kosar, C.M.; Bardenheier, B.H.; Gravenstein, S.A.; et al. Short-term impact of nursing home SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations on new infections, hospitalizations, and deaths. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 2063–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.L.; Halladay, C.W.; Barber, M.; McConeghy, K.W.; Mor, V.; Nanda, A.; Gravenstein, S. Temperature in nursing home residents systematically tested for SARS-CoV-2. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 895–899.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, T.M.; Currie, D.W.; Clark, S.; Pogosjans, S.; Kay, M.; Schwartz, N.G.; Lewis, J.; Baer, A.; Kawakami, V.; Lukoff, M.D.; et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 in a long-term care facility in King County, Washington. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arons, M.M.; Hatfield, K.M.; Reddy, S.C.; Kimball, A.; James, A.; Jacobs, J.R.; Taylor, J.; Spicer, K.; Bardossy, A.; Oakley, C.; et al. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, H.R.; Loomer, L.; Gandhi, A.; Grabowski, D.C. Characteristics of US nursing homes with COVID-19 cases. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1653–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimball, A.; Hatfield, K.M.; Arons, M.; James, A.; Taylor, J.; Spicer, K.; Bardossy, A.C.; Oakley, L.P.; Tanwar, S.; Chisty, Z.; et al. Asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in residents of a long-term care skilled nursing facility—King County, Washington, March 2020. Morb. Mor. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, T.M.; Clark, S.; Pogosjans, S.; Kay, M.; Lewis, J.; Baer, A.; Kawakami, V.; Lukoff, M.D.; Ferro, J.; Brostrom-Smith, C.; et al. COVID-19 in a long-term care facility—King County, Washington, February 27–March 9, 2020. Morb. Mor. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, J.; Volicer, L. Loneliness and isolation in long-term care and the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, H.; Yoshikawa, T.; Ouslander, J.G. Coronavirus disease 2019 in geriatrics and long-term care: The ABCDs of COVID-19. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stall, N.M.; Jones, A.; Brown, K.A.; Rochon, P.A.; Costa, A.P. For-profit long-term care homes and the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks and resident deaths. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 192, E946–E955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisman, D.N.; Bogoch, I.; Lapointe-Shaw, L.; McCready, J.; Tuite, A.R. Risk factors associated with mortality among residents with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in long-term care facilities in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2015957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouslander, J.G.; Grabowski, D.C. COVID-19 in nursing homes: Calming the perfect storm. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2153–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, H.; Gerritsen, D.L.; Backhaus, R.; Boer, B.S.; Koopmans, R.T.; Hamers, J.P.H. Allowing visitors back in the nursing home during the COVID-19 crisis: A Dutch national study into first experiences and impact on well-being. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 900–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas-Herrera, A.; Zalakaín, J.; Lemmon, E.; Henderson, D.; Litwin, C.; Hsu, A.T.; Schmidt, A.E.; Kruse, G.A.F.; Fernández, J.L. Mortality Associated with COVID-19 in Care Homes: International Evidence. Available online: https://ltccovid.org/2020/04/12/mortality-associated-with-covid-19-outbreaks-in-care-homes-early-international-evidence/ (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Li, Y.; Temkin-Greener, H.; Shan, G.; Cai, X. COVID-19 infections and deaths among Connecticut nursing home residents: Facility correlates. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1899–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; McGoogan, J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 323, 1239–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.; States, D.; Bagley, N. The coronavirus and the risks to the elderly in long-term care. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2020, 32, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danis, K.; Fonteneau, L.; Georges, S.; Daniau, C.; Bernard-Stoecklin, S.; Domegan, L.; O’Donnell, J.; Hauge, S.H.; Dequeker, S.; Vandael, E.; et al. High impact of COVID-19 in long-term care facilities, suggestion for monitoring in the EU/EEA, May 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2000956. [Google Scholar]

- Onder, G.; Rezza, G.; Brusaferro, S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA 2020, 323, 1775–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Chen, Y.; Lin, R.; Han, K. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: A comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J. Infect. 2020, 80, e14–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooling, K.; McClung, N.; Chamberland, M.; Marin, M.; Wallace, M.; Bell, B.P.; Lee, G.M.; Talbot, K.; Romero, J.R.; Oliver, S.E. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for allocating initial supplies of COVID-19 vaccine—United States, 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharpure, R.; Guo, A.; Bishnoi, C.K.; Patel, U.; Gifford, D.; Tippins, A.; Jaffe, A.; Shulman, E.; Stone, N.; Mungai, E.; et al. Early COVID-19 first-dose vaccination coverage among residents and staff members of skilled nursing facilities participating in the pharmacy partnership for long-term care program—United States, December 2020–January 2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, R.M.; Hoffman, A.K.; Coe, N.B. Long-term care policy after COVID-19—Solving the nursing home crisis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 903–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corman, V.M.; Landt, O.; Kaiser, M.; Molenkamp, R.; Meijer, A.; Chu, D.K.; Bleicker, T.; Brünink, S.; Schneider, J.; Schmidt, M.L.; et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2000045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.C.; Chaisson, L.H.; Borgetti, S.; Burdsall, D.; Chugh, R.K.; Hoff, C.R.; Murphy, E.B.; Murskyj, E.A.; Wilson, S.; Ramos, J.; et al. Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 mortality during an outbreak investigation in a skilled nursing facility. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2920–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, N.; Barda, N.; Kepten, E.; Miron, O.; Perchik, S.; Katz, M.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Lipsitch, M.; Reis, B.; Balicer, R.D. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in a nationwide mass vaccination setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1412–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Roest, H.G.; Prins, M.; van der Velden, C.; Steinmetz, S.; Stolte, E.; van Tilburg, T.G.; de Vries, D.H. The impact of COVID-19 measures on well-being of older long-term care facility residents in the Netherlands. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1569–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.H.; Donato-Woodger, S.; Dainton, C.J. Competing crises: COVID-19 countermeasures and social isolation among older adults in long-term care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabucchi, M.; De Leo, D. Nursing homes or besieged castles: COVID-19 in northern Italy. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, T.; Barbarino, P.; Gauthier, S.; Brodaty, H.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Xie, H.; Sun, Y.; Yu, E.; Tang, Y.; et al. Dementia care during COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1190–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGilton, K.S.; Escrig-Pinol, A.; Gordon, A.; Chu, C.H.; Zúñiga, F.; Sanchez, M.G.; Boscart, V.; Meyer, J.; Corazzini, K.N.; Jacinto, A.F.; et al. Uncovering the devaluation of nursing home staff during COVID-19: Are we fuelling the next health care crisis? J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 962–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, R.; Nellums, L.B. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, E.J.; Walker, A.J.; Bhaskaran, K.; Bacon, S.; Bates, C.; Morton, C.E.; Curtis, H.J.; Mehrkar, A.; Evans, D.; Inglesby, P.; et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020, 584, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.A.; Jones, A.; Daneman, N.; Chan, A.K.; Schwartz, K.L.; Garber, G.E.; Costa, A.P.; Stall, N.M. Association between nursing home crowding and COVID-19 infection and mortality in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorges, R.J.; Konetzka, R.T. Staffing levels and COVID-19 cases and outbreaks in US nursing homes. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2462–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Wu, P.; Deng, X.; Wang, J.; Hao, X.; Lau, Y.C.; Wong, J.Y.; Guan, Y.; Tan, X.; et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 672–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Marc, G.P.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, L.R.; El Sahly, H.M.; Essink, B.; Kotloff, K.; Frey, S.; Novak, R.; Diemert, D.; Spector, S.A.; Rouphael, N.; Creech, C.B.; et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.; Hirsch, J.S.; Narasimhan, M.; Crawford, J.M.; McGinn, T.; Davidson, K.W.; the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA 2020, 323, 2052–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, M.L.; Grabowski, D.C. Nursing homes are ground zero for COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 1, e200369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, J.K.; Bayne, G.; Evans, C.; Garbe, F.; Gorman, D.; Honhold, N.; McCormick, D.; Othieno, R.; Stevenson, J.E.; Swietlik, S.; et al. Evolution and effects of COVID-19 outbreaks in care homes: A population analysis in 189 care homes in one geographical region of the UK. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2020, 1, e21–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabowski, D.C.; Mor, V. Nursing home care in crisis in the wake of COVID-19. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 324, 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, J. “Abandoned” nursing homes continue to face critical supply and staff shortages as COVID-19 toll has mounted. JAMA 2020, 324, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidambaram, P. State Reporting of Cases and Deaths Due to COVID-19 in Long-Term Care Facilities. Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/state-reporting-of-cases-and-deaths-due-to-covid-19-in-long-term-care-facilities/ (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Grabowski, D.C.; Maddox, K.E.J. Postacute care preparedness for COVID-19: Thinking ahead. JAMA 2020, 323, 2007–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. State Data and Policy Actions to Address Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/state-data-and-policy-actions-to-addresscoronvirus/?utm_source=web&utm_medium=trending&utm_campaign=covid-19 (accessed on 23 May 2020).

| Main Keyword | Related Keywords |

|---|---|

| COVID | “2019-nCoV” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “Corona Virus *” OR “Coronavirus Disease 2019” OR “2019 Coronavirus Disease” OR “New coronavirus disease” OR “Novel coronavirus disease” OR “Novel corona virus *” OR “New corona virus *” |

| AND | |

| Long-term care | “Long term care” |

| NO. | Count | Centrality | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 382 | 0.56 | USA |

| 2 | 183 | 0.08 | Canada |

| 3 | 74 | 0.28 | Italy |

| 4 | 72 | 0.26 | England |

| 5 | 60 | 0.13 | Spain |

| 6 | 51 | 0.08 | Germany |

| 7 | 40 | 0.06 | Netherlands |

| 8 | 35 | 0.03 | France |

| 9 | 27 | 0.10 | Japan |

| 10 | 24 | 0.02 | China |

| NO. | Count | Centrality | Institution | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 80 | 0.41 | University of Toronto | Canada |

| 2 | 39 | 0.11 | Brown University | USA |

| 3 | 26 | 0.24 | Harvard Medical School | USA |

| 4 | 16 | 0.16 | Johns Hopkins University | England |

| NO. | Author | Publications | Author Clusters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zimmerman, Sheryl | 13 | Zimmerman, Sheryl; Nace, David; Gifford, David; Schwandt Michael; Linkgelles, Ruth |

| 2 | Gravenstein, Stefan | 11 | Gravenstein, Stefan; Mor, Vincent; White, Elizabeth M; Blackman, Carolyn; Feifer, Richard A |

| 3 | Kwong, Jeffrey C | 7 | - |

| 4 | Mor, Vincent | 7 | Gravenstein, Stefan; Mor, Vincent; White, Elizabeth M; Blackman, Carolyn; Feifer, Richard A |

| 5 | Gifford, David | 6 | Zimmerman, Sheryl; Nace, David; Gifford, David; Schwandt Michael; Link-gelles, Ruth |

| 6 | Stall, Nathan M | 6 | Stall, Nathan M; Brown, Kevin A; Boscart, Veronique; Jones, Aaron; Costa, Andrew P Schwandt, Michael; Mckee, Geoff; Vijh, R; Harding J; Hayden, A; Lysyshyn, M |

| No. | Count | Centrality | Strength | Reference | Year | Begin | End | Cluster ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 131 | 0.06 | 9.32 | McMichael et al. [19] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #3 |

| 2 | 84 | 0.05 | 2.22 | Arons et al. [20] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #3 |

| 3 | 83 | 0.11 | 0.00 | Abrams [21] | 2020 | - | - | #2 |

| 4 | 55 | 0.11 | 1.89 | Kimball [22] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #3 |

| 5 | 49 | 0.02 | 2.28 | McMichael [23] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #4 |

| 6 | 46 | 0.03 | 0.00 | Simard [24] | 2020 | - | - | #0 |

| 7 | 46 | 0.02 | 4.94 | DAdamo [25] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #1 |

| 8 | 44 | 0.02 | 0.00 | Stall [26] | 2020 | - | - | #2 |

| 9 | 44 | 0.06 | 0.00 | Fisman [27] | 2020 | - | - | #3 |

| 10 | 43 | 0.01 | 0.00 | Zhou [28] | 2020 | - | - | #6 |

| 11 | 40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Ouslander [29] | 2020 | - | - | #3 |

| 12 | 39 | 0.03 | 0.00 | Verbeek [30] | 2020 | - | - | #0 |

| 13 | 39 | 0.01 | 0.00 | Comas [31] | 2020 | - | - | #4 |

| 14 | 38 | 0.01 | 0.00 | White [15] | 2021 | - | - | #2 |

| 15 | 38 | 0.03 | 0.00 | Li [32] | 2020 | - | - | #2 |

| 16 | 36 | 0.02 | 1.84 | Wu [33] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #6 |

| 17 | 36 | 0.03 | 3.25 | Gardner [34] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #7 |

| 18 | 35 | 0.03 | 0.00 | Danis [35] | 2020 | - | - | #3 |

| 19 | 29 | 0.03 | 4.51 | Onder [36] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #6 |

| 20 | 8 | 0.01 | 4.11 | Liu [37] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #6 |

| 21 | 13 | 0.00 | 3.29 | Dooling [38] | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | #5 |

| 22 | 11 | 0.01 | 2.78 | Ghanpure [39] | 2021 | 2021 | 2022 | #5 |

| 23 | 10 | 0.00 | 2.53 | Werner [40] | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | #4 |

| 24 | 10 | 0.01 | 2.53 | Corman [41] | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | #4 |

| 25 | 10 | 0.01 | 2.28 | Patel [42] | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | #3 |

| 26 | 9 | 0.00 | 2.28 | Dagan [43] | 2021 | 2021 | 2022 | #5 |

| 27 | 26 | 0.04 | 0.00 | Van [44] | 2020 | - | - | #0 |

| 28 | 25 | 0.02 | 0.00 | Chu [45] | 2020 | - | - | #0 |

| 29 | 22 | 0.03 | 2.29 | Trabucchi [46] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #0 |

| 30 | 30 | 0.03 | 2.93 | Wang [47] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #1 |

| 31 | 29 | 0.06 | 0.00 | McGitton [48] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #1 |

| 32 | 24 | 0.02 | 1.92 | ArMitage [49] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #1 |

| 33 | 23 | 0.02 | 0.00 | Williamson [50] | 2020 | - | - | #1 |

| 34 | 33 | 0.07 | 0.00 | Brown [51] | 2021 | - | - | #2 |

| 35 | 32 | 0.01 | 0.00 | Gorges [52] | 2020 | - | - | #2 |

| 36 | 26 | 0.00 | 2.26 | CDC [53] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #4 |

| 37 | 16 | 0.02 | 0.00 | He [54] | 2020 | - | - | #4 |

| 38 | 32 | 0.09 | 0.00 | Polack [55] | 2020 | - | - | #5 |

| 39 | 19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Baden [56] | 2021 | - | - | #5 |

| 40 | 19 | 0.03 | 0.00 | Richardson [57] | 2020 | - | - | #6 |

| 41 | 31 | 0.02 | 0.00 | Thompson [6] | 2020 | - | - | #7 |

| 42 | 22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Barnett [58] | 2020 | - | - | #7 |

| 43 | 19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Burton [59] | 2020 | - | - | #7 |

| 44 | 11 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Zimmerman [12] | 2020 | - | - | #7 |

| 45 | 31 | 0.02 | 0.00 | Grabowski [60] | 2020 | - | - | #8 |

| 46 | 11 | 0.00 | 2.18 | Abbasi [61] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #8 |

| 47 | 5 | 0.00 | 2.57 | Chidambaram [62] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #8 |

| 48 | 4 | 0.00 | 2.05 | Grabowski [63] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #8 |

| 49 | 3 | 0.00 | 1.54 | Kaiser [64] | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | #8 |

| No. | Count | Centrality | Keyword | No. | Count | Centrality | Keyword |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 299 | 0.05 | LTC | 14 | 33 | 0.04 | Social isolation |

| 2 | 230 | 0.04 | Nursing home | 15 | 32 | 0.07 | Facility |

| 3 | 81 | 0.06 | Older adult | 16 | 32 | 0.02 | Loneliness |

| 4 | 72 | 0.01 | COVID-19 | 17 | 30 | 0.05 | Outbreak |

| 5 | 68 | 0.02 | LTC facility | 18 | 29 | 0.03 | Older people |

| 6 | 59 | 0.05 | Resident | 19 | 28 | 0.05 | Mortality |

| 7 | 54 | 0.06 | Impact | 20 | 27 | 0.03 | Dementia |

| 8 | 52 | 0.06 | Care | 21 | 27 | 0.03 | United States |

| 9 | 48 | 0.04 | Health | 22 | 26 | 0.07 | Mental health |

| 10 | 40 | 0.05 | Infection | 23 | 26 | 0.02 | Home |

| 11 | 39 | 0.08 | People | 24 | 25 | 0.02 | Prevalence |

| 12 | 35 | 0.03 | Risk | 25 | 25 | 0.02 | Public health |

| 13 | 35 | 0.03 | Quality | 26 | 16 | 0.10 | Nursing home residents |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Z.; Chai, L.; Ma, R. Long-Term Care Research in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Bibliometric Analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091248

Sun Z, Chai L, Ma R. Long-Term Care Research in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Bibliometric Analysis. Healthcare. 2023; 11(9):1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091248

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Zhaohui, Lulu Chai, and Ran Ma. 2023. "Long-Term Care Research in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Bibliometric Analysis" Healthcare 11, no. 9: 1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091248

APA StyleSun, Z., Chai, L., & Ma, R. (2023). Long-Term Care Research in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Bibliometric Analysis. Healthcare, 11(9), 1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091248