Analysis of the Determinants of Stunting among Children Aged below Five Years in Stunting Locus Villages in Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data and Research Samples

2.3. Research Variables

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of the Study

4.2. Suggestion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNICEF; WHO; World Bank. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition: Key Findings of the 2020 Edition of the Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 24, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kemenkes, R.I. Hasil Riset Kesehatan Dasar Tahun 2018. Kementrian Kesehat RI 2018, 53, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Nkurunziza, S.; Meessen, B.; Van geertruyden, J.P.; Korachais, C. Determinants of stunting and severe stunting among Burundian children aged 6–23 months: Evidence from a national cross-sectional household survey, 2014. BMC Pediatr. 2017, 17, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salavati, N.; Bakker, M.K.; Lewis, F.; Vinke, P.C.; Mubarik, F.; Erwich, J.H.M.; van der Beek, E.M. Associations between preconception macronutrient intake and birth weight across strata of maternal BMI. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemenkes. Laporan Kinerja Kementrian Kesehatan Tahun 2020; Jakarta, Indonesia, 2021; pp. 1–209. Available online: https://e-renggar.kemkes.go.id/file2018/e-performance/1-653594-4tahunan-173.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Kementerian PPN/Bappenas. Pedoman Pelaksanaan Intervensi Penurunan Stunting Terintegrasi di Kabupaten/Kota. In Rencana Aksi Nas. dalam Rangka Penurunan Stunting Rembuk Stunting; Jakarta, Indonesia, 2018; pp. 1–51. Available online: https://www.bappenas.go.id (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Akombi, B.J.; Agho, K.E.; Hall, J.J.; Merom, D.; Astell-burt, T.; Renzaho, A.M.N. Stunting and severe stunting among children under-5 years in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2017, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beal, T.; Tumilowicz, A.; Sutrisna, A.; Izwardy, D.; Neufeld, L.M. A review of child stunting determinants in Indonesia. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14, e12617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, T.R.; Chakrabarty, S.; Rakib, M.; Afrin, S.; Saltmarsh, S.; Winn, S. Factors associated with stunting and wasting in children under 2 years in Bangladesh. Heliyon 2020, 6, 604849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, J.P.; Rohner, F.; Petry, N.; Onyango, A.W.; Matji, J.; Bailes, A.; de Onis, M.; Woodruff, B.A. Assessment of the WHO Stunting Framework using Ethiopia as a case study. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direktorat Gizi Masyarakat. Petunjuk Teknis Sistem Informasi Gizi Terpadu (Sigizi Terpadu); Kementerian Kesehatan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019; Volume 1, p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- Sekretariat Wakil Presiden RI. Strategi Nasional Percepatan Pencegahan Stunting 2018–2024 Trend dan Target Penurunan Prevalensi Stunting Nasional; Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020; pp. 1–22. Available online: https://www.tnp2k.go.id/filemanager/files/Rakornis%202018/Sesi%201_01_RakorStuntingTNP2K_Stranas_22Nov2018.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Bahjuri, P. Evaluasi Program Percepatan Pencegahan Stunting. Lokakarya Eval. Pelaks. Stranas Percepatan Pencegah. Stunting Kementeri. Perenc. Pembang. Nasional/Badan Perenc. dan Pembang. Nas. 2020. Available online: https://stunting.go.id/sdm_downloads/evaluasi-program-percepatan-pencegahan-stunting-pelaksanaan-dan-capaian/ (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- TNP2K. 100 Kabupaten/Kota Prioritas untuk Intervensi Anak Kerdil (Stunting): Tim Nasional Percepatan Penanggulangan Kemiskinan. Jakarta 2017, 2, 287. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2015: Reimagine the Future: Innovation for Every Child; New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/state-worlds-children-2015 (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Puslitbang Kementerian Desa PDTT. Intervensi Stunting di Desa di Masa Pandemi COVID-19; Kemendes PDTT: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kemenkes RI. Strategi Komunikasi Perubahan Perilaku Dalam Percepatan Pencegahan Stunting. Kementeri. Kesehat. RI 2018, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kemenkes, R.I. Profil Kesehatan Indonesia Tahun 2020. Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020. Available online: https://www.kemkes.go.id/downloads/resources/download/pusdatin/profil-kesehatan-indonesia/Profil-Kesehatan-Indonesia-Tahun-2020.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Pakpahan, J.P. Cegah Stunting Dengan Pendekatan Keluarga; Penerbit Gava Media: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kementrian Kesehatan RI. Cegah Stuntingtu Penting. Pus. Data Inf. Kementeri. Kesehat. RI 2018, 2, 1–27. Available online: https://www.kemkes.go.id/download.php?file=download/pusdatin/buletin/Buletin-Stunting-2018.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- TNP2K. 1000 Kabupaten/Kota Prioritas Untuk Penanganan Anank Kerdil (Stunting). J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Trihono, M.S. Pendek (Stunting) di Indonesia, Masalah dan Solusinya; Lembaga Penerbit Balitbangkes: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Permanasari, D.S.K.P.Y.; Saptarini, I.; Amaliah, N.; Aditianti, A.; Safitri, A.; Nurhidayati, N.; Sari, Y.; Arfines, P.P.; Irawan, I.R.; Puspitasari, D.S.; et al. Faktor Determinan Balita Stunting Pada Desa Lokus Dan Non Lokus Di 13 Kabupaten Lokus Stunting di Indonesia Tahun 2019. J. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 44, 79–92. Available online: https://ejournal2.litbang.kemkes.go.id/index.php/pgm/article/view/5665 (accessed on 28 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hasnawati, S.L.; Pal, J. Hubungan pengetahuan ibu dengan kejadian stunting pada balita usia 12–59 bulan. J. Pendidik. Keperawatan Kebidanan 2021, 1, 7–12. Available online: https://stikesmu-sidrap.e-journal.id/JPKK/article/view/224 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Chirande, L.; Charwe, D.; Mbwana, H.; Victor, R.; Kimboka, S.; Issaka, A.I.; Baines, S.K.; Dibley, M.J.; Agho, K.E. Determinants of stunting and severe stunting among under-fives in Tanzania: Evidence from the 2010 cross-sectional household survey. BMC Pediatr. 2015, 15, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramdhani, A.; Handayani, H.; Setiawan, A. Hubungan Pengetahuan Ibu Dengan Kejadian Stunting. Semnas Lppm. 2020, 2, 28–35. Available online: https://semnaslppm.ump.ac.id/index.php/semnaslppm/article/view/122/117 (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- BPS Kabupaten Alor. Statistik Kesejahteraan Rakyat Kabupaten Alor 2020; Badan Pusat Statistik Kabupaten Alor: Alor, Indonesia, 2020; Available online: https://alorkab.bps.go.id/publication/2020/12/30/ad3e3306720e25f6898482af/statistik-kesejahteraan-rakyat-kabupaten-alor-2020.html (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- BPS. Tingkat Kemiskinan Kabupaten Alor Tahun 2020. 2021, pp. 1–6. Available online: https://alorkab.bps.go.id/pressrelease/2021/02/09/85/tingkat-kemiskinan-kabupaten-alor--tahun-2020.html (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Notoatmodjo, S. Ilmu Perilaku Kesehatan; Rineka Cipta Jakarta: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hardianty, R. Hubungan Pola Asuh Ibu Dengan Kejadian Stunting Anak Usia 24–59 Bulan di Kecamatan Jelbuk Kabupaten Jember. Jember, Indonesia, 2019. Available online: https://repository.unej.ac.id/bitstream/handle/123456789/92181/Rena%20Hardianty%20-%20152010101099-.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Parke, R.D.; Gauvain, M. Child Psychology A Contemporary Viewpoint, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wati, I.F.; Sanjaya, R. Pola Asuh Orang Tua Terhadap Kejadian Stunting Pada Balita Usia 24-59 Bulan A B S T R A C T Stunting Parenting Toddler *) corresponding author. Wellness Heal. Mag. 2021, 3, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobing, M.L.; Pane, M.; Harianja, E. Pola Asuh Ibu Dengan Kejadian Stuntingpada Anak Usia 24–59 Bulan di Wilayah Kerja Puskesmas Kelurahan Sekupang Kota Batam. J. Kesehat. Masy. 2021, 5, Nomor 1. Available online: https://journal.universitaspahlawan.ac.id/index.php/prepotif/article/view/1630/pdf (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Ibrahim, I.A.; Damayati, D.S. Hubungan Pola Asuh Ibu Dengan Kejadian Stunting Anak Usia 24–59 Bulan Di Posyandu Asoka II Wilayah Pesisir Kelurahan Barombong Kecamatan Tamalate Kota Makassar Tahun 2014. Al-Sihah Pub. Health Sci. J. 2014, VI, 424–436. Available online: https://journal.uin-alauddin.ac.id/index.php/Al-Sihah/article/download/1965/1894/ (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Johnson, R.; Welk, G.; Saint-Maurice, P.F.; Ihmels, M. Parenting styles and home obesogenic environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 1411–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmalasari, Y.; Septiyani, D.F. Pola Asuh Ibu Dengan Angka Kejadian Stunting Balita Usia 6–59 Bulan. J. Kebidanan Malahayati 2019, 5, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanti, E.R. Faktor Jarak Kehamilan yang Berhubungan dengan Kejadian Stunting di Puskesmas Harapan Baru Samarinda Seberang. Borneo Student Res. 2021, 2, 1705–1710. Available online: https://journals.umkt.ac.id/index.php/bsr/article/view/1868/920 (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Nshimyiryo, A.; Hedt-Gauthier, B.; Mutaganzwa, C.; Kirk, C.M.; Beck, K.; Ndayisaba, A.; Mubiligi, J.; Kateera, F.; El-Khatib, Z. Risk factors for stunting among children under five years: A cross-sectional population-based study in Rwanda using the 2015 Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhansyah, N. Faktor-Faktor Yang Berhubungan Dengan Kejadian Stunting Pada Anak Usia 6–23 Bulan di Wilayah Kerja Puskesmas Pisangan Kota Tangerang Selatan Tahun 2018. Univ. Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah Jkt. 2019, 10, Nomor 1. Available online: https://repository.uinjkt.ac.id/dspace/bitstream/123456789/47554/1/NurulFarhanahSyah-FIKES.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- BPS KABUPATEN ALOR. Kecamatan Alor Selatan Dalam Angka 2020. 2020. Available online: https://alorkab.bps.go.id/publication/2020/09/28/eedc6105ff2a8ebffadd2062/kecamatan-alor-selatan-dalam-angka-2020.html (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Dinas Kesehatan Prov NTT. Profil Kesehatan Provinsi NTT Tahun 2012, Revolusi KIA NTT: Semua Ibu Hamil Melahirkan di Fasilitas Kesehatan yang Memadai. Kupang, Indonesia, 2012. Available online: https://pusdatin.kemkes.go.id/resources/download/profil/PROFIL_KES_PROVINSI_2012/19_Profil_Kes.Prov.NTT_2012.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Wamani, H.; Åstrøm, A.N.; Peterson, S.; Tumwine, J.K.; Tylleskär, T. Boys are more stunted than girls in Sub-Saharan Africa: A meta-analysis of 16 demographic and health surveys. BMC Pediatr. 2007, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Chanani, S.; More, N.S.; Osrin, D.; Pantvaidya, S.; Jayaraman, A. Determinants of stunting among children under 2 years in urban informal settlements in Mumbai, India: Evidence from a household census. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2020, 39, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millward, D.J. Nutrition infection and stunting: The roles of de fi ciencies of individual nutrients and foods, and of inflammation, as determinants of reduced linear growth of children. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2022, 30, 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanah, A.R.S.; Nurchayati, S. Hubungan Kejadian Penyakit Infeksi Terhadap Kejadian Stunting Pada Balita 1-4 Tahun. J. Online Mhs. 2013, 6, 65–71. Available online: https://jom.unri.ac.id/index.php/JOMPSIK/article/view/23241/22501 (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Agustin, L.; Rahmawati, D. Hubungan Pendapatan Keluarga Dengan Kejadian Stunting. Indones. J. Midwifery 2021, 4, 30–34. Available online: https://jurnal.unw.ac.id/index.php/ijm/article/view/715 (accessed on 2 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Apriluana, G. Analisis Faktor-Faktor Risiko terhadap Kejadian Stunting pada Balita (0–59 Bulan) di Negara Berkembang dan Asia Tenggara. Media Litbangkes. 2018, 247–256. Available online: https://ejournal2.litbang.kemkes.go.id/index.php/mpk/article/view/472/537 (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Dewi, I.; Suhartatik, S.; Suriani, S. Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi Kejadian Stunting Pada Balita 24–60 Bulan di Wilayah Kerja Puskesmas Lakudo Kabupaten Buton Tengah. J. Ilm. Kesehat. Diagn. 2019, 14, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Improving Child Nutrition—The Achievable Imperative for Global Progress; United Nations Children’s Fund. UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/improving-child-nutrition-achievable-imperative-global-progress?gclid=CjwKCAiA3pugBhAwEiwAWFzwdYboE99Lx9IStiHQ3S6sGKDX_kIWWpRS3OV1DILdBh0MMgQ8Xjp1zBoCItcQAvD_BwE (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Ade Irma Suryani Pane. Pengaruh Kesehatan Lingkungan Terhadap Resiko Stunting Pada Anak di Kabupaten Langkat SKRIPSI. Univ. Sumat. Utara 2019, 2, 99. Available online: http://repositori.usu.ac.id/bitstream/handle/123456789/24351/151101064.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Hasanah, S.; Handayani, S.; Wilti, I.R. Hubungan Sanitasi Lingkungan Dengan Kejadian Stunting Pada Balita di Indonesia (Studi Literatur). J. Keselam. Kesehat. Kerja Lingkung. 2021, 2, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawati, A.D. Hubungan Strata Perilaku Hidup Bersih dan Sehat Rumah Tangga Dengan Kejadian Stunting Pada Balita di Wilayah Upt Puskesmas. 2021. Available online: http://eprints.poltekkesjogja.ac.id/6132/ (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Zhu, W.; Zhu, S.; Sunguya, B.F.; Huang, J. Urban–rural disparities in the magnitude and determinants of stunting among children under five in tanzania: Based on tanzania demographic and health surveys 1991–2016. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depkes, R.I.; Ditjen, P.P.M.; dan, P.L. Pedoman Teknis Penilaian Rumah Sehat. Jakarta, Indonesia, 2007; pp. 1–16. Available online: http://www.ampl.or.id/digilib/read/pedoman-teknis-penilaian-rumah-sehat/1387 (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Keman, S. Enam Kebutuhan Fundamental Perumahan Sehat. J. Kesehat. Lingkung. 2017, 3, 183–194. Available online: https://media.neliti.com/media/publications/3933-ID-enam-kebutuhan-fundamental-perumahan-sehat.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2022).

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 79 | 47.6 |

| Male | 87 | 52.4 |

| Birth spacing | ||

| Normal | 134 | 80.7 |

| Close | 32 | 19.3 |

| History of infectious disease | ||

| Rarely sick | 52 | 31.3 |

| Often sick | 114 | 68.7 |

| Maternal knowledge | ||

| Good | 15 | 9.0 |

| Fair | 31 | 18.7 |

| Less | 120 | 72.3 |

| Mother’s parenting pattern | ||

| Positive | 52 | 32.5 |

| Negative | 112 | 67.5 |

| Parents’ income | ||

| Above minimum wage | 57 | 34.3 |

| Under minimum wage | 109 | 65.7 |

| Health service utilization | ||

| Maximum | 21 | 12.7 |

| Adequate | 37 | 22.3 |

| Less | 108 | 65.1 |

| Household sanitation | ||

| Healthy environment | 62 | 37.3 |

| Unhealthy environment | 104 | 62.7 |

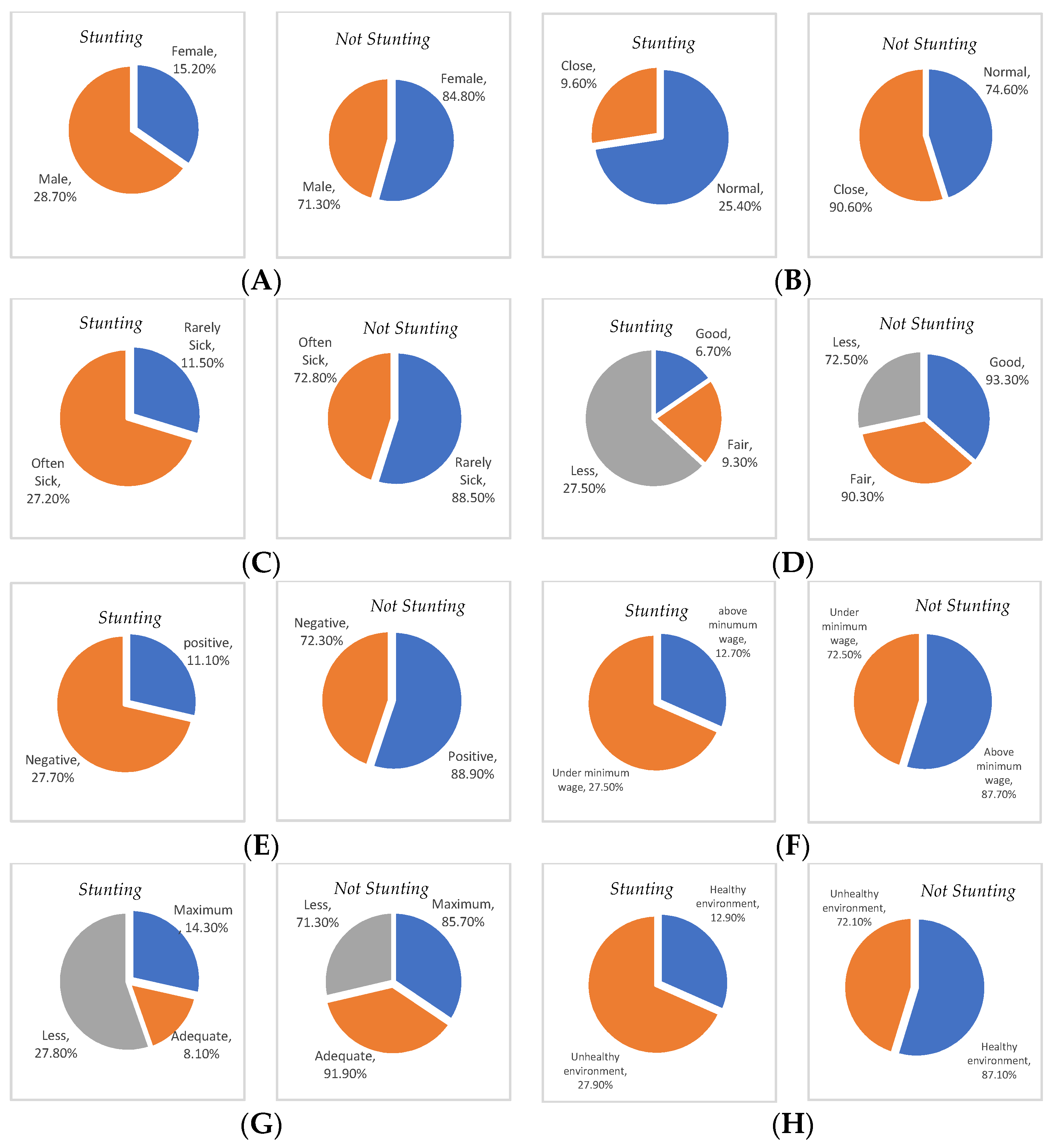

| Variable | Stunting | X2 | AOR | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | Lower | Upper | |||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 67 | 84.8 | 12 | 15.2 | 4.368 ** | Ref | ||

| Male | 62 | 71.3 | 25 | 28.7 | 2.251 | 1.042 | 4.863 | |

| Birth spacing | ||||||||

| Normal | 100 | 74.6 | 34 | 25.4 | 3.817 ** | Ref | ||

| Close | 29 | 90.6 | 3 | 9.6 | 0.304 ** | 0.087 | 1.063 | |

| History of infectious disease | ||||||||

| Rarely sick | 46 | 88.5 | 6 | 11.5 | 5.052 ** | Ref | ||

| Often sick | 83 | 72.8 | 31 | 27.2 | 2.863 | 1.112 | 7.371 | |

| Maternal knowledge | ||||||||

| Good | 14 | 93.3 | 1 | 6.7 | 26.841 *** | Ref | ||

| Fair | 28 | 90.3 | 3 | 9.3 | 1.500 | 0.143 | 15.765 | |

| Less | 87 | 72.5 | 33 | 27.5 | 5.310 *** | 0.671 | 41.997 | |

| Mother’s parenting pattern | ||||||||

| Positive | 48 | 88.9 | 6 | 11.1 | 25.774 *** | Ref | ||

| Negative | 81 | 72.3 | 31 | 27.7 | 3.026 *** | 1.191 | 7.871 | |

| Parents’ income | ||||||||

| Above minimum wage | 50 | 87.7 | 7 | 12.7 | 5.020 ** | Ref | ||

| Under minimum wage | 79 | 72.5 | 30 | 27.5 | 2.712 | 1.108 | 6.643 | |

| Health service utilization | ||||||||

| Maximum | 18 | 85.7 | 3 | 14.3 | 7.638 ** | Ref | ||

| Adequate | 34 | 91.9 | 3 | 8.1 | 0.529 | 0.097 | 2.896 | |

| Less | 77 | 71.3 | 31 | 27.8 | 2.416 | 0.664 | 8.788 | |

| Household sanitation | ||||||||

| Healthy environment | 54 | 87.1 | 8 | 12.9 | 5.033 ** | Ref | ||

| Unhealthy environment | 75 | 72.1 | 29 | 27.9 | 2.610 * | 1.107 | 6.151 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atamou, L.; Rahmadiyah, D.C.; Hassan, H.; Setiawan, A. Analysis of the Determinants of Stunting among Children Aged below Five Years in Stunting Locus Villages in Indonesia. Healthcare 2023, 11, 810. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060810

Atamou L, Rahmadiyah DC, Hassan H, Setiawan A. Analysis of the Determinants of Stunting among Children Aged below Five Years in Stunting Locus Villages in Indonesia. Healthcare. 2023; 11(6):810. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060810

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtamou, Lasarus, Dwi Cahya Rahmadiyah, Hamidah Hassan, and Agus Setiawan. 2023. "Analysis of the Determinants of Stunting among Children Aged below Five Years in Stunting Locus Villages in Indonesia" Healthcare 11, no. 6: 810. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060810

APA StyleAtamou, L., Rahmadiyah, D. C., Hassan, H., & Setiawan, A. (2023). Analysis of the Determinants of Stunting among Children Aged below Five Years in Stunting Locus Villages in Indonesia. Healthcare, 11(6), 810. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060810