Abstract

Medication adherence, especially among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders, is often seen as a major treatment challenge. The purpose of this study is to systematically review studies addressing specific aspects of parental factors that are positively or negatively associated with medication adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. A systematic literature search of English language publications, from inception through December 2021, was conducted from PubMed, Scopus, and MEDLINE databases. This review has complied with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement guidelines. A total of 23 studies (77,188 participants) met inclusion criteria. Nonadherence rates ranged between 8% to 69%. Parents’ socioeconomic background, family living status and functioning, parents’ perception and attitude towards the importance of medication taking in treating psychiatric disorders, and parents’ mental health status are significant parental characteristics associated with medication adherence in children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. In conclusion, by identifying specific parental characteristics related to the medication adherence of children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders, targeted interventions on parents could be developed to guide parents in improving their child’s medication adherence.

1. Introduction

Mental disorders in children and adolescents are common and possess a significant impact on their well-being in the long-run [1]. There are a number of reviews that have reported the significant increase in prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak [2,3,4]. Globally, an estimated 13% of adolescents aged 10–19 years old [5] experienced mental disorders that are often times unrecognized and untreated [6,7]. Some of the most commonly diagnosed mental disorders among children and adolescents are Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), behavioral problems, depression, and anxiety [1,7]. Since there are no definitions that established the exact boundaries of the psychiatric disorder concept, hence, as stated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), mental disorders, also known as psychiatric disorders, may be conceptualized as a “clinically significant behavioral or psychological syndrome or pattern, associated with present distress or disability, and is not merely an expected response to common stressors and losses or a culturally sanctioned response to a particular event, instead was primarily a result of social deviance or conflicts with society, that occurs in an individual” [8] (p. 5). According to the WHO [7], failure to address and deal with adolescents onset mental health conditions may lead to suicide, which is one of the most devastating causes of death, especially among 15- to 19-year-olds. Adolescence is a transitional phase to adulthood that is marked by various biological, cognitive, and psychosocial changes [9]. Hence, it is a crucial period for family, educators, and the community, through various mental health interventions, to promote mental health among adolescents. However, one of the major challenges often faced by psychiatrists in promoting mental well-being and preventing mental health deterioration, especially among children and adolescents diagnosed with mental disorders, is medical adherence towards prescribed treatments and medication [10,11].

According to the WHO [12], medical adherence can be defined as the extent of an individual’s efforts or behavior in observing treatment-related instructions such as taking medication, following a recommended diet, modifying habits, attending treatment appointments, abiding to medication prescription, and corresponding with agreed recommendations from a healthcare professional. Non-adherence is seen as one of the major obstacles and common causes to the increase of mental illness relapses, hospitalization rates, morbidity, and other harmful outcomes [10,11,13,14,15,16]. In reviews conducted among adolescents with psychiatric disorders who were prescribed psychotropic medications or received treatment from psychiatric services, 28% to 75% prematurely dropped out of treatment, a median of 33% adolescents were medically non-adherent, 44% reported no reliable change, 6% reported reliable deterioration, and 13.2% were often re-hospitalized due to suicidal attempts made after discharge within a year [15,17,18,19]. There were not many studies conducted on medical adherence among children, ages 3 to 12 years old, with psychiatric disorder. Findings from Edgcomb et al. [19] suggest that in comparison with adolescents, children tend to have a higher likelihood of reporting adherence to medication. However, according to Edgcomb et al. [19], review on children and adolescents with psychiatric disorder, medical nonadherence is a widespread problem and should be provided with equal importance as children and adolescents with other chronic medical illnesses.

There are many determinants of medication adherence that were reported and categorized in various ways [11,14,16,20,21,22]. The WHO [12] suggested five main categories that covers the multidimensional phenomenon of adherence, which are: (1) socio-economic factors (low socioeconomic status, illiteracy, lack of family support); (2) provider-patient/health care system factors (poor medication distribution, therapeutic relationship); (3) therapy-related factors (complexity of medical regimens, duration of treatments or the immediacy of beneficial effects); (4) condition-related factors (severity of symptoms, rates of progression or level of disability); and (5) patient-related factors (knowledge and beliefs, self-determination). Clinical outcomes pertaining to adherence may be common across all branches of medicine; however, non-adherence among psychiatric patients, in comparison with patients receiving medication or treatment for physical conditions, poses additional challenges, such as having to deal with suicidal ideation and emotional outbursts, relapses as well as stigmatizing attitudes from the patient and the public, that increases the risks of morbidity [13].

Medication adherence, defined as the degree to which patients’ medication-taking behavior corresponds with the agreed, prescribed medication dosing regimen provided by a healthcare professional, is an important subset of the broad study of medical or treatment adherence [12]. The lack of medication adherence poses a significant impact in increasing the risk of psychiatric disorder recurrence and suicidality in adulthood [7,23,24]. Since children and adolescents are still under the purview of parents or parental caregivers, hence adherence among the younger age psychiatric patients are often times largely dependent on the ability of the parent or parental caregiver to understand and follow through with prescribed medication regimens [12].

Parental influence on children and adolescents’ well-being has been widely investigated. Parental influence is inclusive of all influences related to the paternal and maternal figure, that affects the physical, emotional, and intellectual development of a child [25]. According to a review conducted by Rohden et al. [26], parental factors such as income, age characteristics, family structure, parents’ well-being, parental care or neglect and parental arbitration on child’s adherence towards treatment and medication are salient aspects and can be seen as a risk or protective factor of a child’s well-being. Children or adolescents with a psychiatric disorder may possess limited knowledge on mental health and lack of ability in accessing the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), thus requiring parental supervision and guidance in overcoming structural barriers such as financial costs and logistical barriers, as well as adherence challenges such as monitoring symptom severity and ensuring the medication is administered appropriately [27]. Overall, parental factors can be seen as a crucial factor in maximizing good clinical outcomes or causing a major health setback.

There are few reviews that have reported the role of parents as one of the factors associated with medication adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorder [10,15,16]. Both Edgcomb and Zima [10] and Häge et al. [15] investigated predictors of medication adherence only, while Timlin et al. [16] reviewed factors associated with adolescents’ adherence to both medication and non-pharmacological treatments in mental health. A total of 60 studies were reviewed in Edgcomb and Zima [10], Häge et al. [15], and Timlin et al. [16]. The reviews concluded that the range of medication nonadherence was wide, between 6% and 62%, and was considered a common problem in mental health care among children and adolescents with a psychiatric disorder. Factors such as illness severity, comorbidity burden or underlying diagnosis, substance use, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, age, sex, interpersonal care processes and the adolescent’s own beliefs towards treatment emerged as significant predictors of adherence. With regard to parental factors, the findings from these reviews suggests that positive attitudes or the level of support obtained from family members were associated with higher adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders [10,15,16]. Nevertheless, Timlin et al. [16] pointed out the fact that it is challenging to ensure adolescents’ medication adherence to prescribed treatment or medication regimens, as they are transitioning into adulthood and tend to become more independent of their parents. However, these reviews did not provide a clear synthesis of literature that highlights specific components of the parental factors associated with child/adolescent medication adherence. Häge et al. [15] also emphasized the need for future research that involves familial factors associated with medication adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. Thus, the purpose of this review is to evaluate the peer-reviewed literature addressing specific aspects of parental factors that are positively or negatively associated with medication adherence among children and adolescents diagnosed with psychiatric disorders.

The specific questions addressed in this review were:

- How was medication adherence and/or non-adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders defined?

- What are the parental characteristics associated with medication adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders?

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Protocol

This review was performed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021256211).

2.2. Search Strategy

A search of articles published relevant to parenting and medical adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders was conducted. The systematic search of English language publications, from inception through December 2021 was conducted using three main electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, and MEDLINE. As shown in Table 1, searches were piloted, and as a result, a range of search terms with broader descriptions of parenting, medical adherence and psychiatric disorders were tailored to meet specific requirements of each database. All searches were placed within titles and abstracts to maximize the yield of a large data, ensuring as wide as possible a coverage in the review. In addition, through chain searching, reference lists of systematic reviews conducted by Edgcomb and Zima [10], Häge et al. [15], and Timlin et al. [16] were screened and eligible articles were included in this review.

Table 1.

Search terms and strategy used in PubMed, Scopus, and MEDLINE (EbscoHost).

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The systematic searches were designed to identify studies that investigate the relationship of parental factors and child/adolescent medication adherence, targeting all children and adolescents, ages ranging from 1 to 19 years, who were prescribed medication for psychiatric conditions. The present review included studies that (1) were quantitative; (2) discussed any form of parental factor; (3) analyzed medication adherence as the outcome variable (i.e., adherence toward observing instructions on taking prescribed medications); and (4) were published in English or possessed English translations. Since this review is confined to including quantitative study design term only, hence pilot, validation, psychometric, preliminary, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, qualitative, randomized-controlled trial, interventional, and treatment-related studies were excluded from this review, increasing the robustness of findings derived from this review. Articles that discussed medical adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders yet without including any parental factor, and vice versa, were also excluded from the review.

2.4. Study Selection

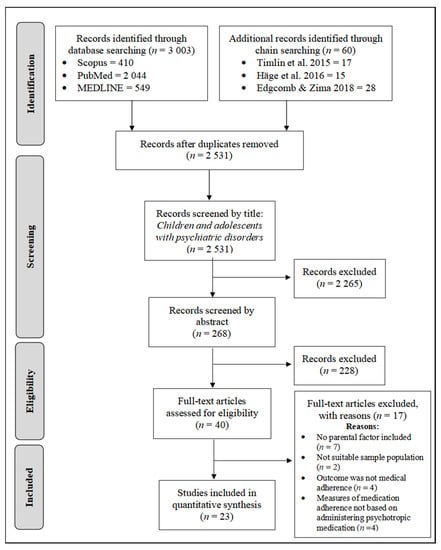

A PRISMA flowchart documenting the process of study selection is shown in Figure 1. After the removal of duplicate publications using the Endnote Program X5 software, the study selection process was screened by two reviewers in three stages. All potential articles identified for inclusion, from eligibility assessment of title and abstract, were independently assessed. If the reviewers coded an article as potentially eligible, the full-texts were then retrieved and reviewed to confirm eligibility. Articles excluded at every stage are agreed to have met at least one of the exclusion criteria outlined. Any disagreement between the reviewers were discussed with a third reviewer until a consensus was reached.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of search results. Note. PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (Edgcomb and Zima [10], Häge et al. [15], and Timlin et al. [16]).

2.5. Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed using a structured data collection sheet developed using the Microsoft Excel software and was piloted beforehand. As shown in Table 2, extracted data includes: (1) study identification features such as authors, year of publication; (2) study characteristics such as study design; and (3) population characteristics and sample size. Data was extracted by one reviewer (CRK) while the second reviewer (CQC) verified the completeness and accuracy of the extracted data. All available relevant data was extracted from the reviews and no additional information was sought from the authors.

Table 2.

Article characteristics (n = 23).

2.6. Quality Assessment

The quality of the paper included was assessed using the “Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)” checklist by von Elm et al., [51]. There are 22 proposed items in the checklist, with items number 6, 12, 14, and 15 having specific variations that assessed 6 components for cohort, case–control and cross-sectional studies. The absence or presence of component stated in each item from the article will be graded with a “0” or a “1”, respectively. A total STROBE score of ≥14/22 assessed for each article are graded as ‘low risk bias’, while articles with a total STROBE score of <14/22 are graded as ‘high risk bias’. The results of the study quality assessment are shown in Supplementary Table S1, where 16 of the articles were rated to be at low risk of bias while the remaining 7 were rated to be at high risk of bias. Common reasons for loss of points in articles were: lack of reporting on potential sources of bias; not addressing the handling of missing data; lacking sample size justifications; insufficient description of statistical analyses; and not reporting of effect sizes, confidence intervals, and funding details.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Due to the differing data sources, heterogeneity and/or the small number of studies included in this review, a quantitative analysis was considered inappropriate and unsuitable. Instead, a narrative overview of the data from included studies (e.g., study characteristics, participants, outcomes, and findings) were presented with tabular summaries for an overall description in this review. The data were synthesized by categorizing the components of parental factors and psychiatric disorders the studies examined. Medication adherence outcomes were extracted and used as the main findings for this review. All data in the table were harmonized so that the influence on adherence refers to an increase in the factor regardless of whether the factor is positive (i.e., associated with higher medication adherence) or negative (i.e., associated with lower medication adherence).

3. Results

In total, 3006 articles pertaining to both parental factors and medication adherence factors among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders were identified from three databases: Scopus (413), PubMed (2044), MEDLINE (549), and chain searching (60). Then, a total of 2531 unduplicated articles were further screened through title and abstracts. Specifically, 532 articles were duplicates and 2265 articles were irrelevant. The remaining 40 eligible articles, after title and abstract screening, were reviewed in their entirety, resulting in the further removal of 17 articles that failed to meet all necessary criteria: parental factors were not thoroughly discussed [52,53,54,55,56,57,58]; target population was not the child or adolescent population with psychiatric disorders [59,60]; outcome measures were not focused on medical adherence [61,62,63,64]; and medication adherence was not measured based on administering psychotropic medications [65,66,67,68]. Finally, only 23 articles were included in this review.

3.1. Summary of Study Characteristics

A total of 77,188 children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders and whom were prescribed psychotropic medication were included in this review (Table 2). A majority of 15 studies was conducted in the United States of America. There were two studies conducted in Canada [38,48], and one study each conducted in Italy [28], Turkey [29], Australia [34], the United Kingdom [41], Mexico [46], and Finland [49]. Even though Harpur et al. [41] conducted the study in the United Kingdom, however participants from Canada, Germany, Australia, Israel, Singapore, Republic of Ireland, South Africa, Brazil, and Malaysia participated in the study through the internet.

Participants were largely recruited from clinical settings, such as the inpatient (n = 10) and outpatient (n = 8) clinical psychiatric facilities. Harpur et al. [41] and Pérez-Garza et al. [46] recruited participants from clinics, yet specific services in which participants were treated were not mentioned. Additionally, Harpur et al. [41] also recruited participants in the community though parent support groups and the internet. Similarly, Demidovich et al. [36] recruited participants through newspapers, radio advertisements, and brochures sent to schools and local mental health centers, as well as program sites affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. On the other hand, Bushnell et al. [32] utilized enrollment files, inpatient and outpatient services, and dispensed prescriptions obtained from the MarketScan Commercial Claims database to identify and recruit participants. Three studies recruited participants from a larger project or separate study [42,44,50].

Almost all studies included in this review (n = 22) possess participants from the adolescent age group. A total of nine studies recruited both children and adolescent participants, with a minimum age of 3 years and a maximum of 18 years. Among the included studies, Demidovich et al. [36] was the only study conducted among children only, with ages ranging between 6 to 11 years old. The included studies employed naturalistic (n = 4), prospective (n = 3), cross-sectional (n = 2), exploratory (n = 1), retrospective (n = 1), and mixed-method (n = 1) study designs. The remaining eleven studies did not mention the study design. The study duration was mentioned in nearly half of the studies (n = 20) included in this review, and they were from a minimum of 3 weeks to a maximum of 3 years.

A total of 18 studies clearly reported the prevalence of medication adherence/nonadherence among the children/adolescents [28,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,38,39,40,43,44,45,47,48,49,50]. The proportion of partial or complete medication adherence ranged from 27% to 78%, while the proportion of medication nonadherence ranged from 8% to 69%.

3.2. Parental Factors Associated with Child/Adolescent Medication Adherence

Detailed information on the association of parental factors and offspring medication adherence is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Association between parental factors and medical adherence.

A few studies investigated the association between family socioeconomic status with medication adherence among children and adolescents (n = 5). Socioeconomic status was found to be positively associated with medication adherence in DelBello et al. [35], Demidovich et al. [36], and Harpur et al. [41]. Bernstein et al. [30] on the other hand reported no significant association between socioeconomic status and medication adherence. Another sociodemographic factor studied in conjunction with children and adolescents medication adherence was parental education (n = 3). It was found that there was no statistically significant relationship between parental education level and medication persistence or commitment [29,37]. Even though Moses [44] reported a positive correlation (p < 0.05) between parents’ education and youth’s commitment to medication, when multiple logistic regression was utilized to evaluate the predictive value of the significant correlates, parent education then demonstrated a non-significant statistical trend (p = 0.08).

Besides that, several studies investigated the influence of family living status on medication adherence and found that there was no significant association [39,40,43,44,48]. In contrast, Atzori et al. [28] stated that youths with poor family structure or are not living with both parents led to a lack of psychotherapy or educational resources to cope with their mental health condition, which in turn made medication the more accessible treatment in comparison to long-term therapy sessions.

Apart from family living status, the role of family functioning and relationship on child or adolescent medication adherence were also investigated. In this regard, family functioning or parental involvement in the child’s medication routine is a strong predictor studied in many articles related to child/adolescent medication adherence (n = 11). All studies included in this review that investigated family functioning and relationship reported that dysfunctional families, with the least affectionate parent–child relationship predicting low medication adherence [30,37,42,43,44,48,49]. Regarding family support, there were several studies that reported non-statistically significant relationship between family support and child/adolescent medication adherence [36,38,40]. In a study conducted by Gearing et al. [38], increased social support was not associated with improved adherence due to the precipitated bias reported from excluding participants with high levels of family support in the study.

Parents’ psychological health, substance use, history of psychotropic medication or psychiatric disorders and lifetime history of parental hospitalization were factors studied in association with their child’s medication adherence (n = 7). According to Burns et al. [31] and Gearing et al. [38], current psychopathology of parents was associated with lower medication adherence of their child, whilst a history of psychopathology was not significantly associated. Similarly, Drotar et al. [37] stated that lifetime history of maternal (r = −0.31; p < 0.01) and paternal (r = −0.44; p < 0.01) hospitalization for psychiatric illness was associated with their child’s medication nonadherence. According to King et al. [43] the mother’s depressive, paranoid, and hostile symptoms were associated with worse medication follow-through of the child.

Similarly, Bushnell et al. [32] also reported that among the number of psychiatric diagnoses that were evaluated in either parent of each child, parent substance use disorder diagnosis was identified as an independent predictor of child’s adherence. However, in contrast, Demidovich et al. [36] and Timlin et al. [49] stated that there was no significant connection observed between parent’s psychiatric problems or substance use towards the child’s medication adherence. Despite having observed a significant association between mother’s depressive, paranoid and hostility symptoms towards the child’s medication adherence, King et al. [43] did not fail to also report that mother’s anxiety symptoms and father’s psychopathology were seen to be non-significant to the child’s medication adherence. According to Bushnell et al. [32], parents’ psychological conditions may be seen as a significant predictor to child/adolescent nonadherence. However, parents with psychiatric disorders who partake in preventative measures or healthy medication adherence behaviors, such as taking daily medications, making trips to the pharmacy, and parents well/preventative visits, encourage adherence in the child [32]. Consequently, parental behavior or attitudes toward psychotropic medication is another major factor which was studied in conjunction with child/adolescent medication adherence (n = 8). In a study conducted by Coletti et al. [33], it was reported that more information is needed to confirm the association between perceived effectiveness and psychiatric condition medication adherence. However, over the years, many studies have reported a significantly positive association between parent’s perceived efficacy and acceptability of psychotropic medication towards the child’s medication persistence or adherence [29,31,41]. Parental self-efficacy, resiliency, emotional support for the child, stigma, perceived costs of medication and parent request of medication discontinuity are of the several parental behaviors that have been reported to decrease the likelihood of the child’s medication adherence [36,41,47].

3.3. Definition of Medication Adherence and Nonadherence

The definition of medication adherence varied across studies, depending on the prescription of medication and clinical outcome. However, the definition of nonadherence, as discontinuation or termination of medication at any given time, seems to be a commonly used definition in all studies. In a study conducted by Moses [44], medication adherence is seen as an expression of commitment, hence the terms used to classify adherent and non-adherent youths in this study are “committed” and “less committed”. In studies conducted by Ayaz et al. [29], Bushnell et al. [32], and Demidovich et al. [36], “medication acceptors/medication persistence” or “medication refusers/discontinuation” were some of the synonymic terms used to address adherence, however the term “compliance/adherence” or “noncompliance/nonadherence” were among the common terms often used interchangeably (cf. Table 4). Majority of the studies (n = 20) included in this review mainly attempted to investigate medication adherence among children or adolescents with psychiatric disorders. However, there are three studies of which objectives were not focused on investigating medication adherence, nonetheless were included in this review. Demidovich et al. [36] reported significant effects of parental medication acceptability and a child’s decision to accept or refuse medication recommendation after the administration of a modular psychosocial treatment, hence were included in this review. Similarly, Hoza et al. [42] emphasizes the primary role of parents as implementers of treatment, indirectly predicting the success or failure of children treatment outcomes. A study conducted by Harpur et al. [41] was mainly focused on describing the psychometric properties of the Southampton ADHD Medication Behavior and Attitudes (SAMBA) scale. Nevertheless, this article was still included in this review due to the reliable and valid function of the scale in measuring parental stigma that significantly predicts pediatric medication adherence.

Table 4.

Description of medication (non)adherence assessment.

All articles included in this review conducted quantitative methods in measuring medication adherence of children and adolescents with psychiatric disorder. Medication adherence was assessed through questionnaires or scales in eleven studies [29,31,33,36,38,40,41,42,45,46,48], structured or semi-structured interviews in six studies [29,34,39,43,44,47], manual or electronic pill counts in five studies [28,30,37,40,50], clinical measurements such as blood levels, serum concentration, etc. in three studies [30,32,37,50], and hospital medical records in two studies [29,35,44,49]. In fourteen of the studies, adherence among children or adolescents with psychiatric disorders was assessed on the basis of questionnaires or interviews with the parents, caregivers, or physicians. In a study conducted by Dean et al. [34], medication adherence was reported primarily by the child and verified by the parents’ report of their child’s medication adherence through an open-ended question on parental involvement in medication monitoring. Similarly, instead of solely relying on self-report medication adherence from patients, Goldstein et al. [40] and Moses [44] also referred to Supplemental Data, such as pill count and medical records, as part of an objective form in measuring medication adherence. Studies conducted by Burns et al. [31], Harpur et al. [41], and Munson et al. [45] correlated the scores to ensure an agreement is reached between parent and child report of adherence. Likewise, Pogge et al. [47] reviewed and corroborated adherence assessment with additional informant when patient’s assessments appeared unreliable.

4. Discussion

The main objective of this review was to summarize existing evidence of the associations between parental factors and medical adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. This study also sought to summarize the definition of medication adherence as employed in the reviewed studies. The overall findings from the 23 studies included in this review reflect the ubiquitous impact parents have in effects to the child’s medication taking behaviors. Since the number of included studies was low and the quality of evidence varied across studies, the review only allows a narrow look at the various factors of medication adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. However, in comparison with three other systematic reviews conducted to explore general factors of medical adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders, this review reports the results of a thorough investigation on parental factors associated with children and adolescents medication adherence. Parental factors were described in various aspects, the most common being parent’s socioeconomic background, family living status and functioning, parent’s perception and attitude towards the importance of medication taking in treating psychiatric disorders, and parental mental health status.

Most studies that investigated the relationship between socioeconomic status and child/adolescent medication adherence showed a significant positive relationship between the variables [35,36,41]. Socioeconomic background has been consistently associated with disparities in child and adolescent mental health [69,70]. This review further confirmed that socioeconomic status may have contributed to mental health disparities through medication adherence. Families with low socioeconomic status may perceive the costs of mental health medication and treatment as an additional burden instead of a need, hence leading to higher levels of nonadherence [35,36,41]. However, reasons were unknown as to why lower and lower-middle socioeconomic status families in the study conducted by King et al. [43] reported higher rates of complete medication follow-through compared to other families.

The findings of this review emphasizes the importance of parent’s perception and attitude towards medication or treatment, which drives children and adolescents’ medication adherence. Parents’ positive attitudes may influence the child or adolescent’s own attitudes toward medication, which in turn predicted the latter’s adherence [16]. A study conducted by Demidovich et al. [36] stated that parents with high self-efficacy and emotional support were associated with medication refusal. Parents lowered sense of impairment related to the child’s symptom severity and their perception of own ability as sufficient in dealing with the child’s psychiatric disorders, reflects a form or parental resiliency, that resulted in the low perceived need for any medication intervention or medication refusal [36]. Correspondingly, psychiatric disorders are often times subject to stigmatization and may also provide further explanation to parents lowered sense of impairment of the child’s symptom severity and lack of motivation to facilitate medication adherence. Stigma was seen to be positively correlated with perceived costs of psychiatric medication and resistance which then directly discourages the child’s medication adherence [41]. According to Atzori et al. [28], the psychiatrist’s approval of parental request for a weekend drug holiday, as part of accurate treatment planning, have significantly contributed to high medication adherence and progressively demystifies stigma and parent’s negative behavior or attitude towards psychotropic medications.

Several studies have shown that parents’ current psychopathology or a history of hospitalization for a psychiatric disorder was associated with lower medication adherence among their offspring [31,37,38]. However, when the type of psychopathology was taken into consideration, there were mixed findings, such as the inconsistent results found in the association between substance use disorders and child medication adherence [32,36,49]. This may point to the relative influence of other factors ensuing from parental psychopathology. For example, parents with a current psychological disorder may be experiencing active symptoms which leads to an inability to cope with the responsibilities of parenting as well as the complexity of psychiatric treatment regime [32,43,48]. A history of hospitalization for psychological disorders may also indicate more serious psychopathology compared with those with no hospitalization history. Parents with poor mental health may also feel overwhelmed by the additional responsibility of caring for their child who is also facing a mental health condition, and therefore may not be able to closely monitor their child’s medication intake, thus leading to non-adherence among their children [48]. These findings are important, as it shows the importance of providing parents who are also struggling with a mental health condition, with adequate support and skills to ensure the successful medical treatment of their children.

The studies reviewed showed that family living status was not correlated with the child or adolescent’s medication adherence [39,40,43,44,48]. Instead, interpersonal factors which permeated family functionality and relationships were more important. The findings are similar to Timlin et al.’s [16] systematic review of factors contributing to adolescents’ adherence to mental health and psychiatric treatment, which included parental support and family cohesion. Family functioning that are problematic or chaotic with low adaptability, least affectionate and uninvolved in the child’s treatment regime were significantly associated with greater noncompliance with medications [30,34,37,43,44,48,49]. According to Dean et al. [34], even though children tend to have greater responsibility for medication administration as they grow older, it is important for parents to still maintain some parental involvement in medication routines. Woldu et al. [50] further emphasized that parental involvement in the child’s medication regimes should persist in not just younger adolescents but also in those who are distractible and forgetful. In contrast, Timlin et al. [49] reported that the child’s close relationship with the mother is a statistically significant factor in predicting nonadherence. The reason remains unknown and in need of clarification as to whether the children/adolescents’ mothers were opposed to treatments [49].

The definitions of adherence and methods used in assessing medication adherence in the 23 studies that were included in this review varied widely. Self-reported measurements such as questionnaires and interviews with children and adolescents were used to obtain information about medication adherence. Self-reported and subjective report of adherence is a feasible method to obtain information as it is less costly and is correlated with clinical outcomes [71]. However, the self-report methods have their weaknesses, including the inability to ascertain the veracity of the reports, and not being able to control for over- or under-reports of adherence [72]. Self-reported adherence may be even more problematic for children and adolescents as they are vulnerable to responding in a socially desirable manner and young children may have difficulty in understanding the concept and measures of medication adherence. Therefore, corroboration of self-report results are conducted with other-report (e.g., Pogge et al., [47]) and objective measures were also employed, such pill counts (e.g., Atzori et al., [28]), clinical measurements such as serum concentration (e.g., Bernstein et al., [30]), and accessing hospital records (e.g., Ayaz et al., [29]). Therefore, both subjective and objective measures of adherence are important, and should be used in combination to obtain the most rigorous results.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

One major strength of this review lies in the attempt to address the importance of parental characteristics in effects to medical adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorder. There was a range of parental factors addressed in this review inclusive of parent’s sociodemographic or socioeconomic characteristics, parenting style, and family functioning, parent’s social characteristics such as perception, stigma and beliefs, as well as parental psychopathology. Due to relative study of heterogeneity in differing components of parental factors, a meta-analysis was not possible. However, the review process was systematic and all studies included were assessed based on strict eligibility and exclusion criteria to ensure all relevant articles were included in this review. In a similar way, the diversity of medical adherence measures across the articles included in this review were positively seen as a means to reduce or overcome information bias. Nevertheless, it may have also contributed to varying results that prevented causal conclusions from being drawn. All the articles included in this review were limited to English peer-reviewed and published articles in international databases, possibly leaving potential studies published in other languages as well as gray literatures and unpublished articles outside the review. This thus affects the applicability of the review as it confines the generalization of the findings. Consequently, further research is needed to address these constraints and guide the improvement of medication adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorder.

4.2. Future Research

The findings of this review will be able to inform future research of the importance of parental factors towards medication adherence. According to the second question addressed in this review, it is shown that parental characteristics, such as parent’s perception and attitude towards medication, parent’s current psychopathology, and parental support or family functioning are significantly associated with medication adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. In relation to that, adopting effective positive parenting approaches, such as positive discipline parenting [73] and strength-based parenting [74] that aims to cultivate positive situations, processes, and qualities in children and adolescents, would facilitate the design of tailored strategies to improve adherence in these patients. In addition, this study also found that parental attitudes toward medication was associated with the adherence of their children. Therefore, future studies could investigate methods to improve parental attitudes toward medication. The findings that parents with current psychopathology and a history of hospitalization for psychiatric disorder may indicate the need to further investigate systemic and holistic intervention methods for families dealing with intergenerational psychiatric disorders.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to systematically review studies on parental factors that were associated with medication adherence among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. Results from total of 23 studies reviewed showed that medication nonadherence was a highly prevalent and widespread problem among children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. We found that parents’ socioeconomic backgrounds, family living statuses and functionings, parents’ perceptions and attitudes towards the importance of medication taking in treating psychiatric disorders, and parents’ own mental health statuses were significant parental characteristics associated with their offsprings’ medication adherence. The present study paves the way for future research by allowing active participation of the parents in improving the child’s medication adherence.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare11040501/s1, Supplementary Table S1: Quality assessment of the studies included based on STROBE.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R.K., C.S.S., K.W.L. and N.I.; Data curation, C.R.K., C.S.S. and C.Q.C.; Formal analysis, C.R.K., K.W.L. and C.S.S.; Funding acquisition, M.C.H. and V.S.; Methodology, C.R.K., K.W.L. and N.I.; Supervision, N.I. and C.S.S.; Validation, V.S., U.V., F.A.S., F.N.A.R., M.R.T.A.H., M.K., F.L.A. and A.N.Y.; Visualization, C.R.K.; Writing—original draft, C.R.K., K.W.L., C.S.S., C.Q.C., M.C.H., U.V., F.A.S., F.N.A.R., M.R.T.A.H., M.K., F.L.A., A.N.Y. and R.S. Writing—review and editing, C.R.K., N.I. and V.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received its funding from the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2020/SS0/UCSI/02/1) from the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- CDC. Data and Statistics on Children’s Mental Health. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/data.html (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- de Miranda, D.M.; da Silva Athanasio, B.; Oliveira, A.C.S.; Simoes-E-Silva, A.C. How Is COVID-19 Pandemic Impacting Mental Health of Children and Adolescents? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meherali, S.; Punjani, N.; Louie-Poon, S.; Abdul Rahim, K.; Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S. Mental Health of Children and Adolescents Amidst COVID-19 and Past Pandemics: A Rapid Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racine, N.; McArthur, B.A.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Zhu, J.; Madigan, J. Global Prevalence of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescents During COVID-19: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Adolescent Health; South East Asia World Health Organizarion: New Delhi, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. On My Mind: Promoting, Protecting and Caring for Children’s Mental Health. 2021. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/state-worlds-children-2021 (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- WHO. Adolescent Mental Health. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nebhinani, N.; Jain, S. Adolescent Mental Health: Issues, Challenges and Solutions. Ann. Indian Psychiatry 2015, 3, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgcomb, J.B.; Zima, B. Medication Adherence among Children and Adolescents with Severe Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 28, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semahegn, A.; Torpey, K.; Manu, A.; Assefa, N.; Tesfaye, G.; Ankomah, A. Psychotropic Medication Non-Adherence and Its Associated Factors among Patients with Major Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Buchman-Wildbaum, T.; Váradi, E.; Schmelowszky, A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Demetrovics, Z.; Urbán, R. Targeting the Problem of Treatment Non-Adherence among Mentally Ill Patients: The Impact of Loss, Grief and Stigma. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eticha, T.; Teklu, A.; Ali, D.; Solomon, G.; Alemayehu, A. Factors Associated with Medication Adherence among Patients with Schizophrenia in Mekelle, Northern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häge, A.; Weymann, L.; Bliznak, L.; Märker, V.; Mechler, K.; Dittmann, R.W. Non Adherence to Psychotropic Medication among Adolescents—A Systematic Review of the Literature. Z. Für Kinder-Jugendpsychiatrie Psychother. 2016, 46, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timlin, U.; Hakko, H.; Heino, R.; Kyngäs, H. Factors that Affect Adolescent Adherence to Mental Health and Psychiatric Treatment: A Systematic Integrative Review of the Literature. Scand. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Psychol. 2015, 3, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, H.A.; Edbrooke-Childs, J.; Norton, S.; Krause, K.R.; Wolpert, M. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Outcome of Routine Specialist Mental Health Care for Young People with Depression and/or Anxiety. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 59, 810–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, A.M.; Boon, A.E.; de Jong, J.T.V.M.; Vermeiren, R.R.J.M. A Review of Mental Health Treatment Dropout by Ethnic Minority Youth. Transcult. Psychiatry 2017, 55, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgcomb, J.B.; Sorter, M.; Lorberg, B.; Zima, B.T. Psychiatric Readmission of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.R. Poor Medication Compliance in Schizophrenia from an Illness and Treatment Perspective. EC Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 3, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Hibdye, G.; Dessalegne, Y.; Debero, N.; Bekan, L.; Sintayehu, M. Prevalence of Drug Nonadherence and Associated Factors among Patients with Bipolar Disorder at Outpatient Unit of Amanuel Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 2013. J. Psychiatry 2015, 28, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nagae, M.R.; Nakane, H.; Honda, S.; Ozawa, H.; Hanada, H. Factors Affecting Medication Adherence in Children Receiving Outpatient Pharmacotherapy and Parental Adherence. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2015, 28, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caqueo-Urízar, A.; Flores, J.; Escobar, C.; Urzúa, A.; Irarrázaval, M. Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents in a Middle-Income Latin American Country. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikec, G.; Kardelen, C.; Pilz González, L.; Mohammadzadeh, M.; Bilaç, Ö.; Stock, C. Perceptions and Experiences of Adolescents with Mental Disorders and their Parents about Psychotropic Medications in Turkey: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilaseca, R.; Rivero, M.; Bersabé, R.M.; Cantero, M.; Navarro-Pardo, E.; Valls-Vidal, C.; Ferrer, F. Demographic and Parental Factors Associated with Developmental Outcomes in Children with Intellectual Disabilities. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohden, A.I.; Benchaya, M.C.; Camargo, R.S.; de Campos Moreira, T.; Barros, H.M.; Ferigolo, M. Dropout Prevalence and Associated Factors in Randomized Clinical Trials of Adolescent Treated for Depression: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Ther. 2017, 39, 971–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovic, A.; Reynolds, K.; McCauley, H.L.; Sucato, G.S.; Stein, B.D.; Miller, E. Parents’ Role in Adolescent Depression Care: Primary Care Provide Perspectives. J. Pediatr. 2015, 167, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atzori, P.; Usala, T.; Carucci, S.; Danjou, F.; Zuddas, A. Predictive Factors for Persistent Use and Compliance of Immediate-Release Methylphenidate: A 36 Month Naturalistic Study. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2009, 19, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayaz, M.; Ayaz, A.B.; Soylu, N.; Yüksel, S. Medication Persistence in Turkish Children and Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 24, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, G.A.; Anderson, L.K.; Hektner, J.M.; Realmuto, G.M. Imipramine Compliance in Adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2000, 39, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, C.D.; Cortell, R.; Wagner, B.M. Treatment Compliance in Adolescents after Attempted Suicide: A 2-Year Follow-Up Study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 948–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, G.A.; Brookhart, M.A.; Gaynes, B.N.; Compton, S.N.; Dusetzina, S.B.; Stürmer, T. Examining Parental Medication Adherence as a Predictor of Child Medication Adherence in Pediatric Anxiety Disorders. Med. Care 2018, 56, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletti, D.J.; Leigh, E.; Gallelli, K.A.; Kafantaris, V. Patterns of Adherence to Treatment in Adolescents with Bipolar Disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2005, 15, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, A.J.; Wragg, J.; Draper, J.; McDermott, B.M. Predictors of Medication Adherence in Children Receiving Psychotropic Medication. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2011, 47, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelBello, M.P.; Hanseman, D.; Adler, C.M.; Fleck, D.E.; Strakowski, S.M. Twelve-Month Outcome Adolescents with Bipolar Disorder Following First Hospitalization for a Manic or Mixed Episode. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidovich, M.; Kolko, D.J.; Bukstein, O.G.; Hart, J. Medication Refusal in Children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder or Conduct Disorder and Comorbid Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Medication History and Clinical Correlates. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 21, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drotar, D.; Greenley, R.N.; Demeter, C.A.; McNamara, N.K.; Stansbrey, R.J.; Calabrese, J.R.; Stange, J.; Vijay, P.; Findling, R.K. Adherence to Pharmacological Treatment for Juvenile Bipolar Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2007, 46, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, R.E. Medication Adherence for Children and Adolescents with First-Episode Psychosis Following Hospitalization. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 18, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaziuddin, N.; King, C.A.; Hovey, J.D.; Zaccagini, J.; Ghaziuddin, M. Medication noncompliance in adolescents with psychiatric disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 1999, 30, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, T.R.; Krantz, M.; Merranko, J.; Garcia, M.; Sobel, L.; Rodriguez, C.; Douaihy, A.; Axelson, D.; Birmaher, B. Medication Adherence among Adolescents with Bipolar Disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpur, R.A.; Thompson, M.; Daley, D.; Abikoff, H.; Sonuga-Barke, E.J. The Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Medication-Related Attitudes of Patients and Their Parents. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2008, 18, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoza, B.; Owens, J.S.; Pelham, W.E., Jr.; Swanson, J.M.; Conners, C.K.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Arnold, L.E.; Kraemer, H.C. Parent Cognitions as Predictors of Child Treatment Response in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2000, 28, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.A.; Hovey, J.D.; Brand, E.; Wilson, R.; Ghaziuddin, N. Suicidal Adolescents after Hospitalization: Parent and Family Impacts on Treatment Follow Through. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, T. Adolescents’ Commitment to Continuing Psychotropic Medication: A Preliminary Investigation of Considerations, Contradictions, and Correlates. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2011, 42, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, M.R.; Floersch, J.E.; Townsend, L. Are Health Beliefs Related to Adherence among Adolescents with Mood disorders? Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2010, 37, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Garza, R.; Victoria-Figueroa, G.; Ulloa-Flores, R.E. Sex differences in severity, social functioning, adherence to treatment, and cognition of adolescents with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. Treat. 2016, 2016, 1928747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogge, D.L.; Singer, M.B.; Harvey, P.D. Rates and Predictors of Adherence with Atypical Antipsychotic Medication: A Follow-Up Study of Adolescent Inpatients. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2005, 15, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S.L.; Baiden, P. An Exploratory Study of the Factors Associated with Medication Nonadherence among Youth in Adult Mental Health Facilities in Ontario, Canada. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 207, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timlin, U.; Hakko, H.; Riala, K.; Rasanen, P.; Kyngas, H. Adherence of 13–17 year old Adolescents to Medicinal and Non-Pharmacological Treatment in Psychiatric Inpatient Care: Special Focus on Relative Clinical and Family Factors. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2014, 46, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woldu, H.; Porta, G.; Goldstein, T.; Sakolsky, D.; Perel, J.; Emslie, G.; Mayes, T.; Clarke, G.; Ryan, N.D.; Birmaher, B.; et al. Pharmacokinetically and Clinician-Determined Adherence to an Antidepressant Regimen and Clinical Outcome in the TORDIA Trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2011, 50, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.C.; DelBello, M.P.; Keck, P.E., Jr.; Strakowski, S.M. Ethnic differences in maintenance antipsychotic prescription among adolescents with bipolar disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2005, 15, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanella, C.A.; Bridge, J.A.; Marcus, S.C.; Campo, J.V. Factor Associated with Antidepressant Adherence for Medicaid Enrolled Children and Adolescents. Ann. Pharmacother. 2011, 45, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C.L.; Li, A.W.; Leung, C.; Chang, W.; Chan, S.K.; Lee, E.H.; Chen, E.Y. Comparing Illness Presentation, Treatment and Functioning between Patients with Adolescent-and Adult-Onset Psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 220, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteni, S.; Giaroli, G.; Rossi, G.; Comelli, M.; Rajendraprasad, M.; Balottin, U. Drug Attitude in Adolescents: A Key Factor for a Comprehensive Assessment. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 34, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakonezny, P.A.; Hughes, C.W.; Mayes, T.L.; Sternweis-Yang, K.H.; Kennard, B.D.; Byerly, M.J.; Emslie, G.J. A Comparison of Various Methods of Measuring Antidepressant Medication Adherence among Children and Adolescents with Major Depressive Disorder in a 12-Week Open Trial of Fluoxetine. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 20, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleath, B.; Domino, M.E.; Wiley-Exley, W.; Martin, B.; Richards, S.; Carey, T. Antidepressant and Antipsychotic Use and Adherence among Medicaid Youths: Differences by Race. Community Ment. Health J. 2009, 46, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, H.; Mazer, C.; Litt, I.F. Compliance and outcome in anorexia nervosa. West. J. Med. 1990, 153, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Howie, L.D.; Pastor, P.N.; Lukacs, S.L. Use of Medication Prescribed for Emotional or Behavioral Difficulties among Children aged 6–17 Years in the United States, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief 2014, 148, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rasaratnam, R.; Crouch, K.; Regan, A. Attitude to Medication of Parents/Primary Carers of People with Intellectual Disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2004, 48, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jou, R.J.; Handen, B.L.; Hardan, A.Y. Retrospective Assessment of Atomoxetine in Children and Adolescents with Pervasive Developmental Disorders. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2005, 15, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.C.; Topalian, A.G.; Starr, B.; Welge, J.; Blom, T.; Starr, C.; Deetz, I.; Turner, H.; Sage, J.; Utecht, J.; et al. The Importance of Second-Generation Antipsychotic-Related Weight Gain and Adherence Barriers in Youth with Bipolar Disorders: Patient, Parent, and Provider Perspectives. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 30, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, T. Parents’ Conceptualization of Adolescents’ Mental Health Problems: Who Adopts a Psychiatric Perspective and Does it Make a Difference? Community Ment. Health J. 2011, 47, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Polier, G.G.; Meng, H.; Lambert, M.; Strauss, M.; Zarotti, G.; Karle, M.; Dubois, R.; Stark, F.M.; Neidhart, S.; Zollinger, R.; et al. Patterns and Correlates of Expressed Emotion, Perceived Criticism, and Rearing Style in First Admitted Early-Onset Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2014, 202, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, R.E.; Brewer, K.B.; Mian, I.; Moore, K.; Fisher, P.; Hamiltom, J.; Mandiberg, J. First-episode Psychosis: Ongoing Mental Health Service Utilization During the Stable Period for adolescents. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2018, 12, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granboulan, V.; Roudot-Thoraval, F.; Lemerle, S.; Alvin, P. Predictive Factors of Post-Discharge Follow-Up Care among Adolescent Suicide Attempters. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2001, 104, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaratou, H.; Vlassopoulos, M.; Dellatolas, G. Factors Affecting Compliance with Treatment in an Outpatient Child Psychiatric Practice: A Retrospective Study in a Community Mental Health Centre in Athens. Psychother. Psychosom. 2000, 69, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schimmelmann, B.G.; Conus, P.; Schacht, M.; Mcgorry, P.; Lambert, M. Predictors of service disengagement in first-admitted adolescents with psychosis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 45, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peverill, M.; Dirks, M.A.; Narvaja, T.; Herts, K.L.; Comer, J.S.; McLaughlin, K.A. Socioeconomic Status and Child Psychopathology in the United States: A Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 83, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiss, F.; Meyrose, A.K.; Otto, C.; Lampert, T.; Klasen, F.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Socioeconomic status, Stressful Life Situations and Mental Health Problems in Children and Adolescents: Results of the German BELLA Cohort-Study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kini, V.; Ho, P.M. Interventions to Improve Medication Adherence: A Review. JAMA 2018, 320, 2461–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Noumani, H.; Wu, J.R.; Barksdale, D.; Sherwood, G.; Alkhasawneh, E.; Knafl, G. Health Beliefs and Medication Adherence in Patients with Hypertension: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelsen, J. Positive Discipline; Ballantine Books: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, L.E. The Relationship between Strength-Based Parenting with Children’s Stress Levels and Strength-Based Coping Approaches. Psychology 2015, 6, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).