Exploring Safety Culture in the ICU of a Large Acute Teaching Hospital through Triangulating Different Data Sources

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Safety Culture in the ICU

1.2. Evaluating SC and Triangulating Data

1.2.1. SC Survey Studies

1.2.2. SC Mixed-Methods Studies

1.2.3. Adverse Event Reporting and Medical Record Review Studies

- (i)

- Staff completion of the HSOPSC survey;

- (ii)

- Using the GTT to carry out a retrospective chart review of a sample of patient charts;

- (iii)

- Reviewing AEs as reported by staff through the hospital electronic AE reporting system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Study Design

- (i)

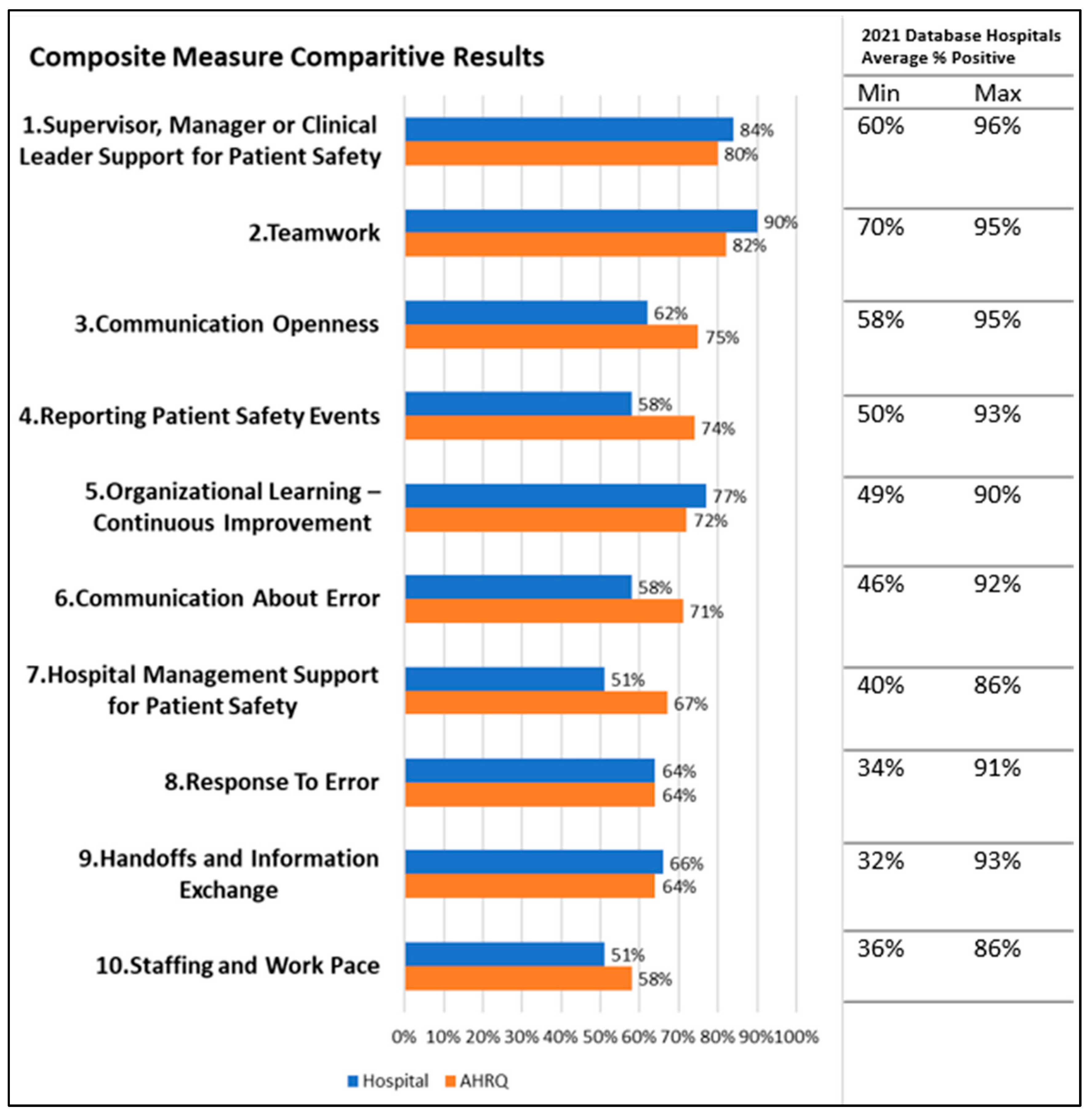

- Staff completion of the HSOPSC survey: Survey data was collected using HSOPSC version 2.0 (Supplementary File S1) approved by the AHRQ [27]. The survey contains a total of 40 survey items, divided across 10 composite measures of SC, primarily using 5-point agreement scales (“Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”) or frequency scales (“Never” to “Always”) with a “Does not apply or Don’t know” option. Composites include Communication About Error, Communication Openness, Handoffs and Information Exchange, Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety, Organizational Learning-Continuous Improvement, Reporting Patient Safety Events, Response to Error, Staffing and Work Pace, Supervisor, Manager, or Clinical Leader Support for Patient Safety and Teamwork. There is also an item on patient safety events the respondent has reported and a further item seeking an overall rating on patient safety for their work unit/area. An additional open-ended question probes perceptions around overall patient safety in the hospital. The demographic data of participants were collected using the same questionnaire, identifying profession, work area, and level of experience. The wording of job roles was adapted to correlate with the Irish setting, as advised by the AHRQ guidance document.

- (ii)

- Using the GTT to carry out a retrospective chart review of a sample of patient charts: As many studies have previously identified low rates of incident reporting [9], a retrospective chart review was completed for a two-week period. The GTT for intensive care was used (Supplementary File S2) to gather this data [28,29,30].

- (iii)

- Reviewing AEs reported by staff from the ICU through the hospital electronic incident reporting system.

2.3. Data Collection Tools, Methods, and Procedures

- (i)

- The HSOPSC, with a participant information leaflet (PIL), was distributed both electronically by email and with paper hard copies. Email links were sent by the critical care administrator, clinical nurse facilitator, and critical care lead to all staff working within the ICU at the time of the study. As the survey was completed anonymously, the Ethics Committee agreed that informed consent was implied through the completion of the survey. An additional follow-up email was sent one month later. To protect against unauthorised access, the survey link was distributed using the hospital internal email system. Hardcopies of the survey and PIL were distributed in person to all professionals working within the ICU at ward rounds, MDT meetings, and quality and audit meetings during February and March 2022.

- (ii)

- Prior to administration of the HSOPSC samples of patients’ electronic patient records (EPR) were reviewed using the GTT for predicting potential patient harm, as outlined in the Institute for Healthcare Improvement protocol [29,30]. Ten records were selected at random from all patients admitted and discharged from ICU, over a two-week period in February 2022. Patients who were admitted <24 h to ICU, under 18, and those patients with a primary psychiatric diagnosis were excluded as outlined in the Institute for Healthcare Improvement guideline. A random number generator was used to ensure random selection. Selected patient charts were anonymised on a password-protected Excel file, stored in the Principal Investigator’s secure folder on the hospital’s internal IT system. EPR records were reviewed for triggers initially by two reviewers, including the main author (EL) and an HSCP colleague who was familiar with the tool. Both reviewers had completed training in the use of the tool. Data was recorded on separate paper forms by each reviewer, as outlined in the Institute for Healthcare Improvement guide [30].

- (iii)

- Reviewing AEs was carried out through an analysis of AEs reported, through the hospital electronic incident reporting system, by staff who work in the ICU. All incidents reported in February 2022 were included. Data provided to the researchers was anonymised.

2.4. Data Analysis

- (i)

- Electronic and hard copy HSOPSC survey data were inputted into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet created and supplied by the AHRQ. All included data were cross-checked for any errors in data entry before analysis. Responses were calculated referencing the AHRQ Guidance document [27]. Missing data and “Does not apply/Don’t know” responses were excluded from calculations. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the mean score and the average percentage of positive responses. The average percentage of positive and negative responses was calculated. The scores were reversed for negatively worded items—these are noted with an (R) after them in the survey. A One-way ANOVA was used for comparison with the AHRQ international database, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Tukey post-hoc tests were used when significance was detected. Demographic data were analysed using descriptive statistics, referencing characteristics of respondents, specifically professional experience. Qualitative data from the open-ended questions of the questionnaire were analysed using content analysis [32]. The data was systematically reviewed and highlighted where SC domains or components were referenced. This was then coded and categorised by SC domain relevance. Further examination of the data was then completed to include barriers and facilitators to patient safety and SC, coded again by SC domains. Categorisation was then completed by grouping the data by positive or negative responses. Following this systematic analysis of the data, themes were formed.

- (ii)

- For the GTT, the triggers were examined for AE occurrence and classified in terms of harm. The National Coordination Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) harm categories are commonly used with the GTT [26] and include Category E: Temporary harm to the patient and required intervention; Category F: Temporary harm to the patient and required initial or prolonged Hospitalisation; Category G: Permanent patient harm Category H: Intervention required to sustain life; Category I: Patient death. After the initial review was completed separately by the two reviewers, the data were collated, and agreement was reached through consensus on rating. An ICU Consultant (EOC) then reviewed the collated data to ensure agreement on the occurrence of an AE and categorisation.

- (iii)

- The reported AE data from the hospital electronic incident reporting systems were reviewed and incidents reported were categorised by one author (EL) according to type, level of harm, and whether the reported AE was related to patients or staff. There was no other formal method of AE reporting in the hospital at the time of the study.

3. Results

3.1. Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture Results (HSOPSC) Results

3.1.1. Demographics

3.1.2. Survey Composites

3.1.3. Safety Rating

3.1.4. Number of Events Reported

3.1.5. Qualitative Data

3.2. AE Results

3.3. GTT Results

3.4. Triangulation of Data

3.4.1. HSOPSC and AE Data

3.4.2. GTT and AE Data

4. Discussion

4.1. Prioritising Safety

4.2. Just Culture

4.3. Reporting Culture

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bienassis, D.E.; Klazinga, N.S. Developing International Benchmarks of Patient Safety Culture in Hospital Care: Findings of the OECD Patient Safety Culture Pilot Data Collection and Considerations for Future Work; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, M.E.; Vaughan, D. 3 Acknowledging and nurturing complementary leadership contributions. In Distributed Leadership in Nursing and Healthcare: Theory, Evidence and Development; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2021; Volume 29. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donovan, R.; Ward, M.; De Brún, A.; Mcauliffe, E. Safety culture in health care teams: A narrative review of the literature. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Patient Safety Action Plan 2021–2030: Towards Eliminating Avoidable Harm in Healthcare; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M.D. Towards a model of safety culture. Saf. Sci. 2000, 36, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, J. Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Hampshire, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Sun, R. A new safety culture measurement tool and its application. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Eng. 2014, 4, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, W.; Li, B.; Conroy, R.; Hickey, A.; Williams, D.J.; Rafter, N. National and Institutional Trends in Adverse Events Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Longitudinal Retrospective Patient Record Review Studies. J. Patient Saf. 2021, 17, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provonost, P.; Ravitz, A.; Stoll, R.; Kennedy, S. Transforming Patient Safety: A Sector-Wide Systems Approach. Report of the WISH Patient Safety Forum. 2015. Available online: https://wish.org.qa/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/017E.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- World Health Organization. WHO Patient Safety. WHO Patient Safety Research: Better Knowledge for Safer Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, R.; Klazinga, N.; Panteli, D.; Quentin, W. (Eds.) Improving Healthcare Quality in Europe: Characteristics, Effectiveness and Implementation of Different Strategies; Health Policy Series, No 53; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Mark, B. Effects of learning climate and registered nurse staffing on medication errors. Nurs. Res. 2011, 60, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livorsi, D.; Knobloch, M.J.; Blue, L.A.; Swafford, K.; Maze, L.; Riggins, K.; Hayward, T.; Safdar, N. A rapid assessment of barriers and facilitators to safety culture in an intensive care unit. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2016, 63, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafter, N. The Frequency and Nature of Adverse Events in Acute Irish Hospitals: The Irish National Adverse Events Study; Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, W.; Rafter, N.; Conroy, R.M.; Stuart, C.; Hickey, A.; Williams, D.J. The Irish National Adverse Event Study-2 (INAES-2): Longitudinal trends in adverse event rates in the Irish healthcare system. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2021, 30, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterson, P.; Carman, E.M.; Manser, T.; Hammer, A. Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSPSC): A systematic review of the psychometric properties of 62 international studies. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churruca, K.; Ellis, L.A.; Pomare, C.; Hogden, A.; Bierbaum, M.; Long, J.C.; Olekalns, A.; Braithwaite, J. Dimensions of safety culture: A systematic review of quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods for assessing safety culture in hospitals. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, M.A.; Aouicha, W.; Sahli, J.; Ben Cheikh, A.; Mtiraoui, A.; Ajmi, T.; Zedini, C.; Chelbi, S.; Ben Rejeb, M.; Mallouli, M. Assessing patient safety culture in 15 intensive care units: A mixed-methods study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzi, S.; Moladoost, A.; Bahrami, M.; Farzi, S.; Etminani, R. Patient Safety Culture in Intensive Care Units from the Perspective of Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2017, 22, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomides, M.D.; de Souza Fontes, A.M.; Silveira, A.O.; Sadoyama, G. Patient safety culture in the intensive care unit: Cross-study. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 13, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardon, R.E.; Khanna, K.; Sorra, J.; Dyer, N.; Famolaro, T. Exploring relationships between hospital patient safety culture and adverse events. J. Patient Saf. 2010, 6, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, P.A.; Houben, R.; Vlayen, A.; Hellings, J.; Pijls-Johannesma, M.; Marneffe, W.; Vandijck, D. Does lean management improve patient safety culture? An extensive evaluation of safety culture in a radiotherapy institute. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, M.; Goh, E.T.; Scott, A.; Martin, G.; Markar, S.; Flott, K.; Mason, S.; Przybylowicz, J.; Almonte, M.; Clarke, J. What has been the impact of COVID-19 on safety culture? A case study from a large metropolitan healthcare trust. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7034. [Google Scholar]

- Granel-Giménez, N.; Palmieri, P.A.; Watson-Badia, C.E.; Gómez-Ibáñez, R.; Leyva-Moral, J.M.; Bernabeu-Tamayo, M.D. Patient Safety Culture in European Hospitals: A Comparative Mixed Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Lomas, J.P. Establishing the use of a safety attitudes questionnaire to assess the safety climate across a critical care network. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2018, 19, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbert, P.D.; Molloy, C.J.; Hooper, T.D.; Wiles, L.K.; Runciman, W.B.; Lachman, P.; Muething, S.E.; Braithwaite, J. The application of the Global Trigger Tool: A systematic review. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2016, 28, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Health Research and Quality. Guidance for HSOPS 2.0 Content; Agency for Health Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/sops/surveys/hospital/AHRQ-Hospital-Survey-2.0-Users-Guide-5.26.2021.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Resar, R.K.; Rozich, J.D.; Simmonds, T.; Haraden, C.R. A trigger tool to identify adverse events in the intensive care unit. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2006, 32, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, L.; Denham, C.R.; Mckeever, M.; Purinton, R.; Guilloteau, F.; Moorhead, J.D.; Resar, R. Global trigger tool: Implementation basics. J. Patient Saf. 2008, 4, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, F.; Resar, R. IHI Global Trigger Tool for Measuring Adverse Events; IHI Innovation Series White Paper; Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Minh Duc, N.T.; Luu Lam Thang, T.; Nam, N.H.; Ng, S.J.; Abbas, K.S.; Huy, N.T.; Marušić, A.; Paul, C.L.; Kwok, J.; et al. A Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS). J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 3179–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Jones, J.; Turunen, H.; Snelgrove, S. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J. Nurs. Educ. Pr. 2016, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relihan, E.; Glynn, S.; Daly, D.; Silke, B.; Ryder, S. Measuring and benchmarking safety culture: Application of the safety attitudes questionnaire to an acute medical admissions unit. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2009, 178, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, L.; Smith, A.; Mcdermott, R.; Breatnach, C.; El-Khuffash, A.; Corcoran, J. Staff Attitudes towards Patient Safety Culture and Working Conditions in an Irish Tertiary Neonatal Unit. 2018. Available online: https://www.lenus.ie/handle/10147/623433 (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Gleeson, L.L.; Tobin, L.; O’Brien, G.L.; Crowley, E.K.; Delaney, A.; O’Mahony, D.; Byrne, S. Safety culture in a major accredited Irish university teaching hospital: A mixed methods study using the safety attitudes questionnaire. Ir. J. Med. Sci. (1971-) 2020, 189, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Services Executive. Patient Safety Strategy 2019–2024; Health Services Executive: Dublin, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Higgins, M.; Singer, S.; Weiner, J. Understanding psychological safety in health care and education organizations: A comparative perspective. Res. Hum. Dev. 2016, 13, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujan, M.A.; Huang, H.; Biggerstaff, D. Trust and Psychological Safety as Facilitators of Resilient Health Care: Working Across Boundaries; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, S. The Development of a Just Culture in the HSE, Health Service Executive, Dublin. 2022. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/nqpsd/qps-incident-management/just-culture-overview.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Bradley, M.; Chahar, P. Burnout of healthcare providers during COVID-19. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasalvia, A.; Amaddeo, F.; Porru, S.; Carta, A.; Tardivo, S.; Bovo, C.; Ruggeri, M.; Bonetto, C. Levels of burn-out among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and their associated factors: A cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital of a highly burdened area of north-east Italy. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sumathipala, M.; Zitnik, M. Population-scale patient safety data reveal inequalities in adverse events before and during COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauletti, G.; Girotto, C.; De Luca, G.; Saieva, A.M. Incident reporting reduction during the COVID-19 pandemic in a tertiary Italian hospital: A retrospective analysis. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2022, 34, mzab161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcnamara, M.; Ward, M.; Teeling, S.P. Making a Sustainable Difference to People, Processes and Systems: Whole-Systems Approaches to Process Improvement in Health Systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.E.; Daly, A.; Mcnamara, M.; Garvey, S.; Teeling, S.P. A Case Study of a Whole System Approach to Improvement in an Acute Hospital Setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, J.B.; Berenholtz, S.M.; Goeschel, C.A.; Watson, S.R.; Holzmueller, C.G.; Thompson, D.A.; Hyzy, R.C.; Marsteller, J.A.; Schumacher, K.; Pronovost, P.J. Assessing and improving safety climate in a large cohort of intensive care units. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 39, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, K.C.; Schwarz, J.J.; Gross, A.K.; Anderson, W.G.; Liu, K.D.; Romig, M.C.; Schell-Chaple, H.; Pronovost, P.J.; Sapirstein, A.; Gropper, M.A. Preventing harm in the ICU—Building a culture of safety and engaging patients and families. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, 1531–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunstan, E.; Cook, J.L.; Coyer, F. Safety culture in intensive care internationally and in Australia: A narrative review of the literature. Aust. Crit. Care 2019, 32, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Staff Positions | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Advanced Practice Nurse (ANP, CNS, CF, CNM) | 17% |

| Staff Nurse | 56% |

| Intern/SHO Doctor | 4% |

| Registrar or Consultant Doctor | 10% |

| Health and Social Care Professional (HSCP) | 11% |

| Other (incl. 1 non-disclosed) | 3% |

| Positive % | Neutral % | Negative % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervisor, Manager or Clinical Leader Support for Patient Safety | ||||

| 1. My supervisor, manager, or clinical leader seriously considers staff suggestions for improving patient safety. | 84 | 12 | 4 | |

| 2. My supervisor, manager, or clinical leader wants us to work faster during busy times, even if it means taking shortcuts. (R) | 77 | 15 | 8 | |

| 3. My supervisor, manager, or clinical leader takes action to address patient safety concerns that are brought to their attention. | 93 | 6 | 1 | |

| Teamwork | ||||

| 1. In this unit, we work together as an effective team. | 97 | 2 | 1 | |

| 2. During busy times, staff in this unit help each other. | 97 | 3 | 0 | |

| 3. There is a problem with disrespectful behaviour by those working in this unit. (R) | 76 | 12 | 12 | |

| Communication Openness | ||||

| 1. In this unit, staff speak up if they see something that may negatively affect patient care. | 76 | 21 | 3 | |

| 2. When staff in this unit see someone with more authority doing something unsafe for patients, they speak up. | 49 | 29 | 22 | |

| 3. When staff in this unit speak up, those with more authority are open to their patient safety concerns. | 66 | 30 | 4 | |

| 4. In this unit, staff are afraid to ask questions when something does not seem right. (R) | 55 | 38 | 7 | |

| Reporting Patient Safety Events | ||||

| 1. When a mistake is caught and corrected before reaching the patient, how often is this reported? | 45 | 28 | 28 | |

| 2. When a mistake reaches the patient and could have harmed the patient but did not, how often is this reported? | 71 | 18 | 10 | |

| Organizational Learning—Continuous Improvement | ||||

| 1. This unit regularly reviews work processes to determine if changes are needed to improve patient safety. | 78 | 14 | 8 | |

| 2. In this unit, changes to improve patient safety are evaluated to see how well they worked. | 75 | 16 | 9 | |

| 3. This unit lets the same patient safety problems keep happening (R) | 80 | 9 | 12 | |

| Communication About Error | ||||

| 1. We are informed about errors that happen in this unit. | 51 | 39 | 10 | |

| 2. When errors happen in this unit, we discuss ways to prevent them from happening again. | 68 | 25 | 7 | |

| 3. In this unit, we are informed about changes that are made based on event reports. | 56 | 31 | 13 | |

| Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety | ||||

| 1. The actions of hospital management show that patient safety is a top priority. | 66 | 22 | 12 | |

| 2. Hospital management provides adequate resources to improve patient safety. | 63 | 15 | 23 | |

| 3. Hospital management seems interested in patient safety only after an adverse event happens. (R) | 25 | 17 | 58 | |

| Response To Error | ||||

| 1. In this unit, staff feel like their mistakes are held against them. (R) | 61 | 22 | 18 | |

| 2. When an event is reported in this unit, it feels like the person is being written up, not the problem. (R) | 62 | 14 | 24 | |

| 3. When staff make errors, this unit focuses on learning rather than blaming individuals. | 66 | 20 | 14 | |

| 4. In this unit, there is a lack of support for staff involved in patient safety errors. (R) | 67 | 21 | 12 | |

| Handoffs and Information Exchange | ||||

| 1. When transferring patients from one unit to another, important information is often left out. (R) | 47 | 16 | 37 | |

| 2. During shift changes, important patient care information is often left out. (R) | 74 | 12 | 15 | |

| 3. During shift changes, there is adequate time to exchange all key patient care information. | 77 | 7 | 16 | |

| Staffing and Work Pace | ||||

| 1. In this unit, we have enough staff to handle the workload. | 50 | 11 | 40 | |

| 2. Staff in this unit work longer hours than is best for patient care. (R) | 32 | 23 | 44 | |

| 3. This unit relies too much on temporary, float, or PRN staff. (R) | 60 | 25 | 15 | |

| 4. The work pace in this unit is so rushed that it negatively affects patient safety. (R) | 62 | 19 | 19 | |

| Positively worded | Negatively Worded (R) | |||

| Positive | “Strongly Agree/Agree” “Always/Most of the time” | “Strongly Disagree/Disagree” “Never/Rarely” | ||

| Neutral | “Neither Agree nor Disagree/Sometimes”. | “Neither Agree nor Disagree/Sometimes”. | ||

| Negative | “Strongly Disagree/Disagree” “Never/Rarely” | “Strongly Agree/Agree” “Always/Most of the time” | ||

| Sample Qualitative Comments | Staff Category | |

|---|---|---|

| Teamwork positive comment | “Fantastic teamwork between all forms of staff.” | Other/Not disclosed |

| Staffing Concerns | “Adequate staffing would positively impact patient safety, ensuring they are receiving the correct level of care”. | Health & Social Care Professional (HSCP) |

| Communication | “I would also like to see a clear follow through and delivery of information to staff. How many near misses/adverse events etc. and what is being done to minimise further incidents” | Advanced Nurse Practitioner (ANP, CNS, CF, CNM) * |

| Reporting Culture | “I have been blamed for putting too many incident reports, so now avoid them as far as possible.” | Staff Nurse |

| Equipment | “Sometimes lack of equipment, bed spaces too small/not fit for purpose can cause safety concerns, which are well known, but little has changed.” | Staff Nurse |

| AE Data | GTT | |

|---|---|---|

| ICU admissions | 123 | 123 |

| Charts reviewed | - | 10 |

| Triggers | - | 43 |

| No. of events | 11 | 16 |

| Near miss | 1 | 0 |

| Temp harm | 3 | 15 |

| Harm | 7 | 1 |

| Medication-related | 2 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liston, E.; O’Connor, E.; Ward, M.E. Exploring Safety Culture in the ICU of a Large Acute Teaching Hospital through Triangulating Different Data Sources. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3095. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11233095

Liston E, O’Connor E, Ward ME. Exploring Safety Culture in the ICU of a Large Acute Teaching Hospital through Triangulating Different Data Sources. Healthcare. 2023; 11(23):3095. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11233095

Chicago/Turabian StyleListon, Ellen, Enda O’Connor, and Marie E. Ward. 2023. "Exploring Safety Culture in the ICU of a Large Acute Teaching Hospital through Triangulating Different Data Sources" Healthcare 11, no. 23: 3095. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11233095

APA StyleListon, E., O’Connor, E., & Ward, M. E. (2023). Exploring Safety Culture in the ICU of a Large Acute Teaching Hospital through Triangulating Different Data Sources. Healthcare, 11(23), 3095. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11233095