Abstract

Game usage has recently been increasing, but the actual situation of game usage and issues among pregnant women are not clarified. The purpose of this prospective longitudinal study was to examine changes in game usage, lifestyle, and thoughts about game usage during pregnancy depending on parity and to clarify the characteristics of pregnant women who continue to use games. We conducted three web surveys in early, mid- and late pregnancy in 238 pregnant women. For primiparous women who continued to use games, there was a significant increase in game usage time from early to late pregnancy (p = 0.022), and 25.0% of those women had anxiety that they might have a game addiction. For primiparous women in mid-pregnancy and multiparous women in early and late pregnancy, the proportions of women who thought that they could not use gaming sufficiently due to pregnancy and child-rearing were significantly higher in women who continued to use games. In both primiparous women and multiparous women, the proportion of partners who used games was significantly higher in women who continued to use games. It is necessary for midwives to discuss with pregnant women and their partners about game usage and to provide advice about control of game usage in daily life.

1. Introduction

The population engaged in game usage has been increasing globally [1], and a subset of this population has problematic game usage [2]. It was reported that the frequency of video game use was associated with self-worth and social acceptance for young women negatively [3]. In addition, Stockdale et al. reported that excessive gaming was related to depressive symptoms and decreased feelings of parental efficacy among mothers [4]. Nakayama et al. reported that problematic game usage was related to the young age of the people with habitual game usage [5]. Since game usage has recently been increasing in the younger generation, the number of people with problematic game usage may increase in the future. There have been few reports on the actual situation of game usage and issues regarding game usage among pregnant women. We previously reported that the proportion of pregnant women using games is approximately 40% in early pregnancy [6] and that women tend to stop playing games or reduce their game usage time after pregnancy [7]. However, changes in game usage and game usage time with the advance of the gestational period have not been reported. Considering that there are differences in daily life such as the time spent on childcare or sleep [8] and the status of nutritional intake [9] between primiparous women and multiparous women, there may be different characteristics of game usage according to parity.

We previously reported that although some women stop playing games when they become pregnant, there are some women who continue to play games after pregnancy. Moreover, women who continue to play games after pregnancy are likely to have anxiety that they might have a game addiction, and it is likely that their partners also play games [7]. We also reported that there was a correlation between game usage time and anxiety in women in early pregnancy about whether they might have a game addiction [6]. However, changes in the characteristics of game usage in pregnant women who continue to use games during their subsequent pregnancy period have not been clarified. Various physical and psychological changes occur during pregnancy. It has been reported that hormonal fluctuations and anatomical changes during pregnancy induce sleep deficiency [10,11] and that the proportion of pregnant women engaging in physical activity decreases with the advance of the gestational period [12,13]. Anxiety about giving birth [14] and a desire for improvement in lifestyle have also been reported for pregnant women since pregnant women become more concerned about the health of the mother and fetus [15]. Thoughts about game usage may also change in pregnant women with the advance of the gestational period. The purpose of this prospective longitudinal study was to examine changes in game usage, lifestyle, and thoughts about game usage during pregnancy in primiparous women and multiparous women and to clarify the characteristics of pregnant women who continue to use games.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

We conducted this prospective study between April 2021 and December 2022 at a birth center for low-risk pregnant women. This birth center handles approximately 700 births annually in one provincial city in Japan. The necessary sample size was determined to be 172 by using effect size (0.3), α coefficient (0.05), power (0.95), and degree of freedom (2). The sample size was determined to be 645 considering the number of uncollected samples.

2.2. Participants

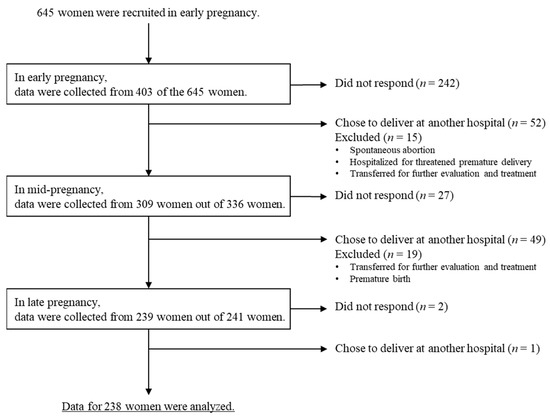

A total of 693 pregnant women who visited the birth center for a medical check during their first trimester were recruited and were informed about the study’s objectives and methodologies. Of those women, 645 pregnant women agreed to take part in the study. A flow diagram of this prospective study is shown in Figure 1. QR codes for the online survey were distributed to the participants, and the survey was conducted by using Survey Monkey, an online tool for creating and managing questionnaires. The participants were informed that they were deemed to have consented to participate in the study by checking a box for consent “agree” before they started answering an online questionnaire. With regard to consent for participation from each subject, we explained that each subject could participate in the study voluntarily. It was clarified that refusing to participate would not cause harm, and this assurance was provided to all potential participants. Additionally, participants were informed that the collected data would exclusively serve the purpose of the study but not for any other objectives. The survey conducted online ensured the participants’ anonymity. Response rates to the questionnaires were 62.5% (403/645) at early pregnancy, 47.9% (309/645) at mid-pregnancy and 37.1% (239/645) at late pregnancy. We analyzed data for 238 women (238/645: 36.9%) for whom there were responses at all three time points.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the prospective study.

2.3. Data Collection

Women over 20 years of age who were married (or have a partner) and who intended to give birth at this birth center were included. Women with multiple pregnancies and women facing challenges in completing the questionnaire due to mental or physical issues were excluded. We also excluded women such as those with a previous history of severe hypertension, diabetes, schizophrenia, or severe depression before pregnancy and those currently undergoing treatment for these conditions. We recruited subjects who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and provided an explanation sheet of the study.

The questionnaire for early pregnancy included four sections. The first section was about background characteristics; the second section was about game usage during pregnancy; the third section was about daily life behavior and thoughts about game usage; and the fourth section was about the Internet Gaming Disorder Scale (IGDS), which consists of nine dichotomous items related to Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD). In the first section, we asked about employment (working, not working), smoking habits (never, used to smoke but stopped before pregnancy, used to smoke but stopped after pregnancy, current smoking), alcohol consumption habits (never, used to drink but stopped before pregnancy, used to drink but stopped after pregnancy, current drinking), partner’s age, and the partner’s game usage in the past month. The second section comprised inquiries concerning game use and the daily time allocated to playing games in the past month. In the third section, we asked about the following: average daily sleeping hours; consistency in wake-up time and bedtime; occurrence of days when insufficient sleep was due to game usage; occurrence of days when meals were not cooked due to game usage; occurrence of days without regular meals (3 meals/day) due to game usage; frequency of consuming ready-to-eat meals (e.g., instant food, precooked food, and fast food); perception of game usage negatively affecting a child’s or children’s development; perception of game usage being addictive; experience of ever feeling addicted to games; and feelings of not having enough time to play games due to pregnancy or child-rearing. In the fourth section, we used the IGDS, which consists of nine dichotomous items related to IGD, where each response is either ‘yes’ (1 point) or ‘no’ (0 points), with a cutoff value set at 5 points [16]. Sumi et al. translated the IGDS into Japanese [17]. The questionnaire for mid-pregnancy also consisted of four sections. In the first section, only two questions on gestational weeks of the pregnant woman and the partner’s game usage were included. The questions in the second, third, and fourth sections were the same as those at early pregnancy. The questionnaire in late pregnancy was exactly the same as that in mid-pregnancy. Information including age and parity from medical records was obtained about each subject with consent.

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the background characteristics of the subjects. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to examine the normality of the variables. Comparisons of sleeping hours for women in the three periods and comparisons of game usage times for women in the three periods were performed by Friedman’s test with a Bonferroni correction for post hoc analysis. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare age, partner’s age, sleeping hours, and game usage time between the two groups in parity. In the analysis, the gaming usage time of the pregnant women who did not play games was considered as 0 min. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test with a Bonferroni correction was used for comparisons between the two groups in parity, employment, smoking habit, alcohol drinking habit before pregnancy, game usage, partner’s game usage, daily life behaviors, thoughts on games, and the IGDS score.

In order to compare game usage time and various factors that may be related to game usage, the women were divided into three groups: Group A (women who played games in all three periods), Group B (women for whom there was a change in game usage in the three periods), and Group C (women who did not play games in any of the three periods). Comparisons of game usage times of women in Group A in the three periods and comparisons of game usage times of women in Group B in the three periods were performed by Friedman’s test with a Bonferroni correction for post hoc analysis. In the analysis of Group B, the gaming usage time of the pregnant women who did not play games was considered as 0 min. Comparisons of sleeping hours for women, and age of the partner in the three groups (Group A, Group B, and Group C) were performed by the Kruskal–Wallis test with a Bonferroni correction for post hoc analysis. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test with a Bonferroni correction was used for comparisons of employment, smoking habit, alcohol drinking habit before pregnancy, game usage, partner’s game usage, daily life behaviors, and thoughts on games among the three groups. We set a p value of less than 0.05 as a statistical significance. We conducted all statistical analyses by using SPSS statistics ver.28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Background Characteristics of All Subjects

The mean numbers (±standard deviation: SD) of gestational weeks at the time of the questionnaire response were 10.8 (±1.9) at early pregnancy, 26.2 (±1.1) at mid-pregnancy, and 36.4 (±1.1) at late pregnancy. The mean (±SD) age of pregnant women was 31.6 (±4.7) years. Out of 238 pregnant women, 190 women (79.8%) were working. In terms of smoking, 183 women (76.9%) had never smoked, 39 women (16.4%) used to smoke but stopped before pregnancy, 14 women (5.9%) used to smoke but stopped after pregnancy, and two women (0.8%) were smoking. In terms of alcohol consumption, 43 women (18.1%) had never drunk alcohol, 122 women (51.3%) used to drink but stopped before pregnancy, and 73 women (30.7%) used to drink but stopped after pregnancy. The mean (±SD) durations of sleeping time per day in the 238 women were 7.4 (±1.4) h in early pregnancy, 7.0 (±1.1) h in mid-pregnancy, and 6.7 (±1.4) h in late pregnancy. Sleeping time in mid-pregnancy and that in late pregnancy were both significantly shorter than that in early pregnancy (p = 0.003 and p < 0.001, respectively). There was no significant difference in the proportions of women who played games in the three periods (42.4% in early pregnancy, 33.6% in mid-pregnancy, and 34.9% in late pregnancy).

3.2. Comparison of Background Characteristics and Various Factors in Primiparous Women and Multiparous Women

The age of multiparous women (32.6 ± 4.5 years) was significantly greater than that of primiparous women (30.5 ± 4.6 years) (p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in background characteristics such as age of the partner, employment, smoking habit, and alcohol drinking before pregnancy between primiparous women and multiparous women. The median periods of game usage time per day (10–90 percentile) for primiparous women were 0.0 (0.0–120.0) min in early pregnancy, 0.0 (0.0–120.0) min in mid-pregnancy, and 0.0 (0.0–180.0) min in late pregnancy. The median periods of game usage time per day (10–90 percentile) for multiparous women were 0.0 (0.0–60.0) min in early pregnancy, 0.0 (0.0–60.0) min in mid-pregnancy, and 0.0 (0.0–60.0) min in late pregnancy. There were no significant differences in game usage time among the three periods for both primiparous women and multiparous women. In early pregnancy, the game usage time in primiparous women was significantly longer than that in multiparous women (p = 0.006).

A comparison of background characteristics and various factors for primiparous women (n = 113, 47.5%) and multiparous women (n = 125, 52.5%) is shown in Table 1. We divided responses to daily life behaviors and thoughts on games into “yes” (frequently and sometimes) and “no” (not at all) for comparison. In both primiparous women and multiparous women, the sleeping hours in late pregnancy were significantly shorter than those in early pregnancy (p = 0.007 and p < 0.001, respectively). In all three periods, the sleeping hours in multiparous women were significantly shorter than those in primiparous women (p = 0.008, p = 0.007, and p = 0.014, respectively).

Table 1.

Changes in background characteristics and various factors among the three periods in primiparous women and multiparous women.

In multiparous women, there were significant differences in the proportion of women with regularity of wake-up time and bedtime and the proportion of women with a high frequency of eating ready-to-eat meals among the three pregnancy periods. In early pregnancy, the proportion of primiparous women who reported that there were days on which they could not cook their own meals due to game use was higher than the proportion of multiparous women (p = 0.049).

3.3. Comparison of Background Characteristics and Various Factors among the Three Groups According to Changes in Game Usage during Pregnancy

We divided the 238 women based on changes in their game usage during pregnancy into three groups: Group A (n = 59, 24.8%), Group B (n = 63, 26.5%), and Group C (n = 116, 48.7%). There were no significant differences in the proportions of primiparous women and multiparous women among the three groups (Group A: 54.2% and 45.8%, respectively; Group B: 49.2% and 50.8%, respectively; Group C: 43.1% and 56.9%, respectively). We compared background characteristics of the 238 women among Group A, Group B, and Group C and compared those between primiparous women and multiparous women as well. There were no significant differences in the background characteristics (age of partner, employment, smoking habit, alcohol drinking before pregnancy) among Group A, Group B, and Group C. There were also no significant differences in these background characteristics between primiparous women and multiparous women.

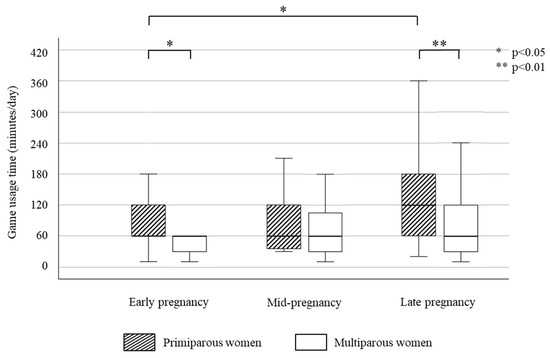

The median periods of game usage time per day (10–90 percentile) for women in Group A were 60.0 (20.0–180.0) min in early pregnancy, 60.0 (20.0–180.0) min in mid-pregnancy, and 90.0 (30.0–180.0) min in late pregnancy, and there was a significant increase from early pregnancy to late pregnancy (p = 0.013). Changes in game usage time of pregnant women in Group A for primiparous women and multiparous women are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Changes in game usage time of pregnant women who played games during all pregnancy periods (Group A) for primiparous women and multiparous women. Friedman’s test (Primiparous women: p = 0.002, Multiparous women: p = 0.302).

For primiparous women in Group A, the periods of game usage were 60.0 (10.0–300.0) min in early pregnancy, 60.0 (30.0–210.0) min in mid-pregnancy, and 120.0 (20.0–360.0) min in late pregnancy, and there was a significant increase from early pregnancy to late pregnancy (p = 0.022). On the other hand, for multiparous women in Group A, the periods of game usage were 60.0 (20.0–132.0) min in early pregnancy, 60.0 (10.0–180.0) min in mid-pregnancy, and 60.0 (20.0–186.0) min in late pregnancy, and there were no significant differences among the three periods.

The median periods of game usage time (10–90 percentile) per day for women in Group B were 30.0 (0.0–120.0) min in early pregnancy, 0.0 (0.0–66.0) min in mid-pregnancy, and 0.0 (0.0–96.0) min in late pregnancy, and there was a significant decrease from early pregnancy to mid-pregnancy (p = 0.033). For primiparous women in Group B, the periods of game usage were 30.0 (0.0–168.0) min in early pregnancy, 0.0 (0.0–84.0) min in mid-pregnancy, and 0.0 (0.0–120.0) min in late pregnancy, and there were significant decreases from early pregnancy to mid-pregnancy and late pregnancy (p = 0.047 and p = 0.033, respectively). For multiparous women in Group B, the periods of game usage were 10.0 (0.0–60.0) min in early pregnancy, 0.0 (0.0–67.0) min in mid-pregnancy, and 0.0 (0.0–60.0) min in late pregnancy, and there was no significant difference in game usage time among the three periods. In early pregnancy and late pregnancy, game usage times in primiparous women were significantly longer than those in multiparous women in both Group A and Group B (Group A: p = 0.021 and p = 0.004, respectively; Group B: p = 0.01 and p = 0.01, respectively). In all three pregnancy periods, game usage time of women in Group B were significantly shorter than women in Group A in both primiparous women and multiparous women (early pregnancy: p = 0.018 and p < 0.001, respectively; mid-pregnancy: p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively; early pregnancy: p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively).

In all three groups, mean sleeping hours in late pregnancy were shorter than those in early pregnancy (p = 0.005, p = 0.001, and p < 0.001, respectively), and mean sleeping hours of multiparous women in Group A and Group C were shorter in late pregnancy than in early pregnancy (p = 0.016 and p = 0.005, respectively). In Group A, the proportion of women who consumed ready-to-eat meals at a frequency of three or more days per week was higher in early pregnancy than in mid-pregnancy and late pregnancy (p = 0.006), and a significant difference among the three periods was found in only multiparous women (p = 0.021).

Comparisons of game usage, daily life behavior, and thoughts about game usage among Group A, Group B, and Group C for each trimester are shown in Table 2(a–c). In both primiparous women and multiparous women, the proportion of partners who used games was significantly higher in Group A in all pregnancy periods. In early pregnancy, sleeping hours in multiparous women were significantly longer in Group A than in Group C (p = 0.029). There were significant differences in the proportions of women who responded that they could not sleep due to game use among Group A, Group B, and Group C in both primiparous women and multiparous women. A significant difference among Group A, Group B, and Group C in the proportions of women who responded that game usage by mothers produces a negative environment for child/children’s development was found only in primiparous women. In mid-pregnancy and late pregnancy, there was a significant difference in the proportions of primiparous women with regularity of wake-up time and bedtime among Group A, Group B, and Group C. For primiparous women in the three gestational periods and multiparous women in late pregnancy, there were significant differences among Group A, Group B, and Group C in the proportions of women who had anxiety that they might have a game addiction. For primiparous women in mid-pregnancy and multiparous women in early and late pregnancy, there were significant differences among Group A, Group B, and Group C in the proportions of women who thought that they could not use gaming sufficiently due to pregnancy and child-rearing.

Table 2.

Comparison of background characteristics and various factors among the three groups in primiparous women and multiparous women. (a) Early pregnancy. (b) Mid-pregnancy. (c) Late pregnancy.

3.4. Internet Gaming Disorder Scale (IGDS)

In the 238 women in early pregnancy, one woman (0.4%) had 5 points for the IGDS, one woman (0.4%) had 4 points, one woman (0.4%) had 3 points, four women (1.7%) had 2 points, 14 women (5.9%) had 1 point, and 218 women (91.6%) had 0 points. In mid-pregnancy, none (0.0%) had more than 4 points, one woman (0.4%) had 3 points, three women (1.3%) had 2 points, 10 women (4.2%) had 1 point, and 224 women (94.1%) had 0 points. In late pregnancy, none (0.0%) had more than 4 points, one woman (0.4%) had 3 points, two women (0.8%) had 2 points, five women (2.1%) had 1 point, and 230 women (96.6%) had 0 points. In the early pregnancy period, there was only one woman with a score of more than 5 points, which indicates a high level of dependence on Internet games. There were no significant differences in the proportion of the IGDS scores between primiparous women and multiparous women in the early, mid, and late pregnancy periods. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.58.

4. Discussion

This study is the first longitudinal survey on game usage among pregnant women. We showed that approximately half of the pregnant women did not engage in any game use. Since women who did not play games during pregnancy (Group C) included a significantly higher proportion of women who responded that game usage by mothers produces a negative environment for child/children’s development, this may be one of the reasons that women did not engage in any game use.

On the other hand, approximately one-fourth of the pregnant women continued their game usage during three periods of pregnancy (Group A). For women in Group A, there was an increase in game usage time in late pregnancy in primiparous women, but there were no changes in the three periods in multiparous women. In addition, the game usage time in primiparous women was longer than that in multiparous women in both early pregnancy and late pregnancy. We found that primiparous women may use their pre-birth maternity leave in late pregnancy to play games. Multiparous women understand that their physical condition might not be good after childbirth and that they will have less leisure time due to childcare. Therefore, they may adapt their game usage into their daily lives during pregnancy. However, since primiparous women do not have childcare experience, they may think that they can maintain game usage time after childbirth. Therefore, for primiparous women, midwives need to provide information and opportunities to consider their postpartum life in detail during pregnancy or before pregnancy and guide them to adjust game usage with postpartum daily life in mind.

The other approximately one-fourth of the pregnant women changed their game usage during three periods of pregnancy—they played games during one period but not during another (Group B). In Group B, the proportion of women who used games was 74.2% in early pregnancy, but it decreased to 32.3% in mid-pregnancy and 29.0% in late pregnancy. For primiparous women in Group B, there were significant decreases in game usage time from early pregnancy to mid-pregnancy and late pregnancy. On the other hand, for multiparous women in Group B, there was no significant change in game usage time. The reason for this result might be that these women in Group B decided to continue or discontinue game usage according to their own preferences, and they adapted game usage to the physical and psychological changes caused by pregnancy.

We showed that sleeping hours in late pregnancy were shorter than those in early pregnancy in both primiparous women and multiparous women and that multiparous women had shorter sleeping hours than did primiparous women in all periods. These findings are consistent with the results of previous studies [8,10,11]. Suzuki et al. reported that shorter sleeping hours in multiparous women were due to the burden of childcare [8]. In Japan, it has been reported that the time spent on household and childcare duties by women is longer than that by men [18] and that there are many mothers who feel a significant burden of childcare responsibilities [19]. Multiparous women may have a short sleeping time and a short game usage time since their free time is limited due to housework and childcare.

Women who continued to play games in all three periods (Group A) had no changes in sleeping hours during pregnancy, but they included a high proportion of women with irregular sleep habits. That was noticeable in primiparous women. Since it has been reported that additive gaming might be associated with poor quality of sleep [20], game usage in primiparous women who continued to play games might be a reason for irregular sleeping habits. On the other hand, multiparous women might not have had sleep disorders because their game usage time was not long enough to affect their sleeping states.

It has been reported that sleep disorders during a period of one month before birth could be a risk factor for weak labor in primiparous women [21]. It has also been reported that severely disrupted sleep was related to longer labor duration and that women with severely disrupted sleep were 5.2 times more likely to have cesarean section [22]. Therefore, for primiparous women who continue to use games during pregnancy, it is necessary for midwives to assess the impact of game usage on quality of sleep and to advise them to control their game usage.

We found that women who continued to use games during pregnancy (Group A) had feelings of anxiety that they might have a game addiction and a feeling of dissatisfaction that they could not play games sufficiently due to their pregnant state or childcare, suggesting that they had psychological ambivalence.

Since it has been reported that maternal anxiety and stress can have an impact on neural development in the fetus [23], it is necessary to reduce stress in pregnant women. The late pregnancy period, when mothers feel both excitement about the upcoming birth and anxiety about the process of labor, is a period that requires various preparations for childbirth and parenting. It has been reported that learning about childbirth in childbirth preparation classes is beneficial as a preparation for labor and that such preparation leads to better acceptance of childbirth in the postpartum period [24]. It has also been reported that participants in childbirth preparation classes have interests in both childbirth and parenting preparation and that they highly valued classes conducted by midwives that included these contents [25]. As the approach by midwives is effective in preparing for childbirth and parenting, midwives can inform pregnant women about potential physical and psychological issues that might occur due to the continuation of game usage during pregnancy and make pregnant women control their game usage.

In women who continued game usage during pregnancy (Group A), the proportion of partners who used games was high in both primiparous women and multiparous women. It has been reported that women engage in gaming in response to their partner’s gaming behavior since game usage is a shared recreational activity among couples [26]. We previously reported that women whose partners engage in game usage are more likely to continue gaming after pregnancy [7]. For the issues of game use during pregnancy, an approach for not only pregnant women but also their partners is needed.

Midwives should inform both women and their partners about potential issues that could occur from the continuation of game usage during pregnancy in childbirth preparation classes or before pregnancy. It is important for partners to recognize the impact of their own gaming behaviors and control their game usage.

There are several limitations in the present study. As this study utilized an online survey, it is restricted to individuals with internet access, potentially leading to a dominance of specific characteristics. The responses are based on the participants’ subjective experiences. In the present study, we could not show that short game usage time is better for pregnancy progress or perinatal events in pregnant women, although we compared various factors according to gaming time. A prospective comparative study between short and long game usage times is needed in the future. The differences in game usage time between multiparous women and primiparous women in early pregnancy might be due to the time needed for childcare by multiparous women. A question about game usage during the first pregnancy in multiparous women might be needed. In this study, we found that the use of games by pregnant women is associated with the gaming behavior of their partners. Further surveys regarding partners’ game usage are necessary. In this prospective study, 79 women dropped out after mid-pregnancy. There were 50 women who were unable to decide on a birth facility due to the COVID-19 pandemic and were transferred to other hospitals after mid-pregnancy. Out of the distributed QR codes, 29 women did not respond, but we did not ask the reasons for their non-response. Further research is needed to examine the potential issues faced by pregnant women who continue to use games during pregnancy, the gaming habits of partners, and the required educational approaches and support.

5. Conclusions

An increase in game usage time was found at late pregnancy in primiparous women who continued to use games during pregnancy. Those primiparous women had psychological ambivalence about their game use, and they had a higher proportion of partners who used games. Midwives need to include partners in their approach and should discuss with couples about game usage and advise them to control game usage in daily life. From a public health perspective, providing information about game usage and establishing a support system to promote appropriate usage and a balanced lifestyle are necessary.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S. and T.Y.; methodology, H.S. and T.Y.; software, H.S.; validation, H.S.; formal analysis, H.S. and T.Y.; investigation, H.S. and T.Y.; resources, H.S.; data curation, H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.; writing—review and editing, T.Y.; visualization, H.S.; supervision, T.Y.; project administration, T.Y.; funding acquisition, T.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tokushima University Hospital (The date of approval: 22 March 2021, Approval No. 3945).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study by checking the button to agree to participate in the survey on the first page of the web survey before starting to answer.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available because of privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to show their appreciation to the pregnant women who participated in the present study. The authors are also grateful to Shusaku Kamada and the midwives in Keiai Ladies Clinic for contributing to the data collection for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wijman, T. Global Games Market Report, Light Version. [Internet]. Newzoo. [Updated 25 June 2022]. Available online: https://newzoo.com/resources/trend-reports/newzoo-global-games-market-report-2020-light-version (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Internet gaming addiction: A systematic review of empirical research. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2012, 10, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Nelson, L.J.; Carroll, J.S.; Jensen, A.C. More than a just a game: Video game and internet use during emerging adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockdale, L.; Coyne, S.M. Parenting paused: Pathological video game use and parenting outcomes. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2020, 11, 100244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, H.; Matsuzaki, T.; Mihara, S.; Kitayuguchi, T.; Higuchi, S. Relationship between problematic gaming and age at the onset of habitual gaming. Pediatr. Int. Off. J. Jpn. Pediatr. Soc. 2020, 62, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, H.; Yasui, T. Game Usage in Pregnant Women at Early Gestation in Japan. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2022, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Yasui, T. Comparisons of game usage time and game usage-related factors in Japanese women before pregnancy and during early pregnancy. Int. J. Nurs. Midwifery 2023, 15, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, K.; Ohida, T.; Sone, T.; Takemura, S.; Yokoyama, E.; Miyake, T.; Harano, S.; Nozaki, N.; Motojima, S.; Suga, M.; et al. An epidemiological study of sleep problems among the Japanese pregnant women. Jpn. J. Public Health 2003, 50, 526–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Hamada, H.; Matsuzaki, M.; Ota, E. Analysis of Differences in Lifestyle and Nutrition Intake of Women in Each Stage of Pregnancy. Bull. St. Luke’s Int. Univ. 2022, 8, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, S.M.; Attarian, H.; Zee, P.C. Sleep disorders in perinatal women. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 28, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, A.K.; Uhde, T.W. Perinatal Sleep Problems: Causes, Complications, and Management. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 45, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haakstad, L.A.; Voldner, N.; Henriksen, T.; Bø, K. Physical activity level and weight gain in a cohort of pregnant Norwegian women. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2007, 86, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNallo, J.M.; Williams, N.I.; Downs, D.S.; Le Masurier, G.C. Walking for health in pregnancy: Assessment by indirect calorimetry and accelerometry. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 2008, 79, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huizink, A.C.; Mulder, E.J.; de Medina, P.G.R.; Visser, G.H.; Buitelaar, J.K. Is pregnancy anxiety a distinctive syndrome? Early Hum. Dev. 2004, 79, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, M.; Lindkvist, M.; Eurenius, E.; Persson, M.; Mogren, I. Change of lifestyle habits—Motivation and ability reported by pregnant women in northern Sweden. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. Off. J. Swed. Assoc. Midwives 2017, 13, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemmens, J.S.; Valkenburg, P.M.; Gentile, D.A. The Internet Gaming Disorder Scale. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 27, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumi, S.; Nishiyama, T.; Ichihashi, K.; Hara, M.; Kuru, Y.; Nakajima, R. Internet gaming disorder scale Japanese version. Jpn. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2018, 47, 109–111. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office. Declining Birthrate White Paper, Chapter 1–5, Men’s Time for Housework and Childcare. [Internet]. Government of Japan. [Updated July 2022]. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/shoushi/shoushika/whitepaper/measures/w-2022/r04webhonpen/index.html (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Mishina, H.; Takayama, J.I.; Aizawa, S.; Tsuchida, N.; Sugama, S. Maternal childrearing anxiety reflects childrearing burden and quality of life. Pediatr. Int. Off. J. Jpn. Pediatr. Soc. 2012, 54, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, L.T. Internet gaming addiction, problematic use of the internet, and sleep problems: A systematic review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, H.; Hasegawa, J.; Sekizawa, A. Sleep disorder as a risk factor for weak labor. J. Jpn. Soc. Perinat. Neonatal Med. 2015, 50, 1226–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.A.; Gay, C.L. Sleep in late pregnancy predicts length of labor and type of delivery. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 191, 2041–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bergh, B.R.; Mulder, E.J.; Mennes, M.; Glover, V. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: Links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005, 29, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanzadeh, R.; Abbas-Alizadeh, F.; Meedya, S.; Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S.; Mirghafourvand, M. Perceptions of primiparous women about the effect of childbirth preparation classes on their childbirth experience: A qualitative study. Midwifery 2021, 103, 103154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barimani, M.; Frykedal, K.F.; Rosander, M.; Berlin, A. Childbirth and parenting preparation in antenatal classes. Midwifery 2018, 57, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, S.M.; Busby, D.; Bushman, B.J.; Gentile, D.A.; Ridge, R.; Stockdale, L. Gaming in the game of love: Effects of video games on conflict in couples. Fam. Relat. 2012, 61, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).