Perceptions of Barriers and Facilitators to a Pilot Implementation of an Algorithm-Supported Care Navigation Model of Care: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Setting and Model of Care

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Themes and Subthemes

3.1.1. An Algorithm Alone Is Not Enough

“One challenge is identifying the patients who are vulnerable and likely to represent to hospital…an algorithm is a really good start as this helps target the right people and they get the right support. I don’t think the algorithm alone is enough’ but it is a good start.”(P1)

“With high scores there was definite a chance of representing. It’s not perfect but it’s better than just going by who presented three times in the last year. Another way of weeding out the patients we needed to see compared to the patients that just needed a general practitioner visit.”(P3)

“If you want to look at how you can reduce the impact these patients have on acute services—expensive bed-based service—it (the algorithm) does capture patients from this perspective. It’s like early intervention in chronic disease program, and there’s a whole body of work that needs to happen before people get to that point.”(P4)

“This project was not just about implanting a new model of care in a specific area; this is broad change at a significant level that is going to affect not just one unit of medicine but multiple and this is a hard and difficult thing to coordinate.”(P4)

“It’s years away as it’s a significant change and would take at least ten years for it to mature enough. Considering we have talked about it for three and a half years and only done a small pilot project. So, given that’s our baseline for how long implementation takes to occur it will take a lot of change to support it.”(P4)

3.1.2. Health Service Culture

“We are still adopting specialist care largely focused on single diseases, and with training programs that do not have any involvement or minimal training in community health. Concerns about control of patient care being lost if multidisciplinary care plans are adopted.”(P3)

“Another one would be the culture and capacity to change. Culturally the organisation was invested in bed-based care and hesitant to pilot innovative projects with a culture of learning around working with these complex individuals.”(P1)

“It (targeted care navigation) sits strongly with me and my professional identity…my profession is about enabling people to better manage their own health and wellbeing.”(P1)

“Given my background is predominantly in primary care I’m passionate about primary care and providing care and services outside of hospital and in the community.”(P2)

3.1.3. Leadership

“We needed higher engagement from the department of health with our health service, and performance meetings and looking at engaging them on this journey first.”(P3)

“They didn’t give us clarity early on of what the readmission risk score actually meant…you’d have to think there was an increase in risk as your score went up.”(P3)

“I think at that high level the direction given by the government about the funding model was not clear.”(P4)

“The hospital can think this is a loss if you move patients away from current hospital-based funding.”(P3)

“There was a perspective that there was a lot of risk with the project, so we didn’t get support to be on board with the project in its entirety.”(P2)

“At the time when we were involved there wasn’t a great appetite for risk and so we were tasked with providing a very limited level of service. We kind of put a toe in the water and did something, so we were involved but not do a whole lot.”(P5)

“It’s difficult—it’s a system change across the health service and it’s near impossible if you don’t have strong organisational support.”(P2)

“The aim was to prevent hospital readmissions but key performance indicators were not clarified.”(P6)

“It’s critical that we do implement a (targeted care navigation) model. Looking at how we evaluate our out of hospital services and at how we can better care for patients outside of hospital walls. I think a (targeted care navigation) model will be a driver to do this.”(P1)

3.1.4. Staffing and Resources

“The other big enabler was the clinician. Because of their personality they got a lot more done than someone who was meeker or milder and not pushy for the patient… It was never clear to me, if we were to get positive results, how much of it would be process or person related.”(P5)

“(The project was negatively) Impacted by only having one part-time staff member. The more people you have, the more you can facilitate the project.”(P6)

“A whole group of patients may have missed out because (of) resourcing due to it only being a pilot.”(P4)

“The clinician did an amazing job advocating for patients to be seen before they left hospital.”(P4)

“In an ideal world we wouldn’t have just one person to provide care navigation and facilitate this.”(P4)

“You need good, sophisticated IT systems to flag patients at risk.”(P2)

“We have programs to build upon and some services can already be used without reinventing the wheel from scratch and building a whole new program. We don’t want to create another silo of care for people.”(P4)

“Our clinical systems are quite complex and don’t necessarily facilitate good connected care—we need systems to do that.”(P1)

“You have patients that have social complexities that will always be at risk and they need more intervention than a four-week program.”(P2)

3.1.5. Patient Experience of Care

“I think the patients that were involved really appreciated having the follow-through, from the organisation, with their care. They felt they were cared about with the follow-up phone calls and sometimes it’s the simple things and it doesn’t need to be complicated.”(P4)

“Staff on the wards really felt comfortable that someone would follow them (patients) up.”(P3)

“As nice as it was for patients for feeling better, the readmission rate wasn’t reduced. The quality of care improved, the quality of discharge improved but in terms of the outcome we were looking at there was no obvious benefit.”(P5)

“Some patients don’t do what you think they should do, which is an issue.”(P4)

“People with chronic illness who are probably just expected to be readmitted. These people actually do not mind being in hospital, and coming back to hospital was not such a bad thing.”(P6)

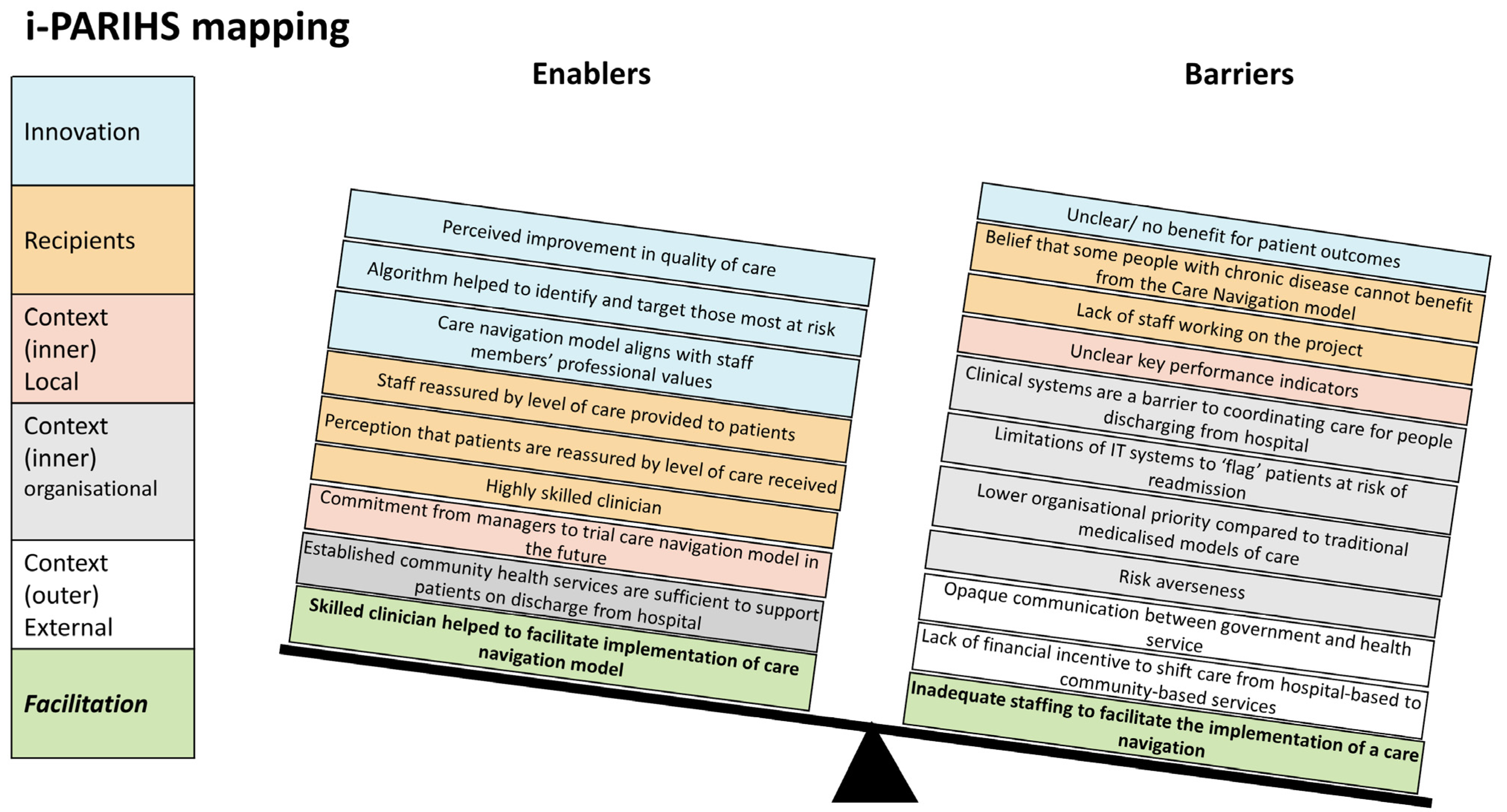

3.2. Mapping Themes to i-PARIHS Framework

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question | TDF Domain |

|---|---|

| What is your understanding of discharge support and drivers of hospital readmission? | Knowledge |

| What was your role in the project? What skillset/previous experience did you bring to the project? | Skills |

| Do you think the use of readmission risk algorithm best described the patients at risk of hospital readmission? Why? | Social/professional role and identity |

| Comment on (i) Targeted Care Navigation cohort (ii) Hospital eligibility criteria (iii) services/model of care and (iv) define KPI | N/A |

| How does this project align with your professional identity and professional standards? | Social/professional role and identity |

| How difficult or easy was it for you to implement the program? | Beliefs about capabilities |

| What do you see were the main enablers for implementing this project? Explain | N/A |

| What do you see were the main barriers for implementing this project? Explain | N/A |

| How confident were you that it could be implemented? | Optimism |

| What do you see were the strengths of the project? Explain | N/A |

| What do you see were the limitations of the project? Explain | N/A |

| What do you think would happen/or what would be the consequences of permanently implementing this (both positive and negative)? | Beliefs about consequences |

| Are there any incentives to do this? (personal, program, organisational and Departmental level) | Reinforcement |

| Have you made a decision whether or not you would like to have this project implemented? | Intentions |

| How much would you like to see this type of intensive care coordination implemented? | Goals |

| Can you see this type of intervention being something that you usually do (become part of routine practice) | Memory, attention and decision processes |

| To what extent do physical or resource factors facilitate or hinder you to do intensive care coordination? e.g., Training; Management meetings | Environmental context and resources |

| To what extent did peers/managers/patients facilitate or hinder use of the intervention? | Social influences |

| Does using the package evoke an emotional response? If so, what? | Emotion |

| Are there procedures or processes can be in place that better encourage intensive care coordination? | Behavioural regulation |

| How can we make it sustainable? | N/A |

References

- Longman, J.M.; Rolfe, M.I.; Passey, M.D.; Heathcote, K.E.; Ewald, D.P.; Dunn, T.; Barclay, L.M.; Morgan, G.G. Frequent hospital admission of older people with chronic disease: A cross-sectional survey with telephone follow-up and data linkage. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves-Bradley, D.C.; Lannin, N.A.; Clemson, L.M.; Cameron, I.D.; Shepperd, S. Discharge planning from hospital. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD000313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henschen, B.L.; Theodorou, M.E.; Chapman, M.; Barra, M.; Toms, A.; Cameron, K.A.; Zhou, S.; Yeh, C.; Lee, J.; O’Leary, K.J. An Intensive Intervention to Reduce Readmissions for Frequently Hospitalized Patients: The CHAMP Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.M.; Cousins, G.; Clyne, B.; Allwright, S.; O’Dowd, T. Shared care across the interface between primary and specialty care in management of long term conditions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2, CD004910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoren, B.M.; Butler, D.; Levine, B.S.; Anderson, B.J.; Laffel, L.M. Reducing acute adverse outcomes in youths with type 1 diabetes: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2003, 112, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doessing, A.; Burau, V. Care coordination of multimorbidity: A scoping study. J. Comorbidity 2015, 5, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, J.; Bainbridge, D.; Whelan, T.J.; Brazil, K.; Parpia, S.; Wiernikowski, J.; Schiff, S.; Rodin, G.; Sergeant, M.; Howell, D. Evaluation of a specialized oncology nursing supportive care intervention in newly diagnosed breast and colorectal cancer patients following surgery: A cluster randomized trial. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.; Valaitis, R.K.; Lam, A.; Feather, J.; Nicholl, J.; Cleghorn, L. Navigation delivery models and roles of navigators in primary care: A scoping literature review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, R.; Weller, C.; Srikanth, V.; Shannon, B.; Andrew, N. Community care navigation intervention for people who are at-risk of unplanned hospital presentations. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, CD014713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.M.; Hernandez, E.A.; Levin, S.; De Vaan, M.; Kim, M.O.; Lynch, C.; Roth, A.; Brewster, A.L. Effect of Social Needs Case Management on Hospital Use Among Adult Medicaid Beneficiaries: A Randomized Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plant, N.A.; Kelly, P.J.; Leeder, S.R.; D’Souza, M.; Mallitt, K.A.; Usherwood, T.; Jan, S.; Boyages, S.C.; Essue, B.M.; McNab, J.; et al. Coordinated care versus standard care in hospital admissions of people with chronic illness: A randomised controlled trial. Med. J. Aust. 2015, 203, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, R.B.; Galbraith, A.A.; Burns, M.E.; Vialle-Valentin, C.E.; Larochelle, M.R.; Ross-Degnan, D. A Patient Navigator Intervention to Reduce Hospital Readmissions among High-Risk Safety-Net Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, L.R.; Gould, P.; Berkowitz, S.A.; James, G.D.; Marks, K. Impact of a Social Work Care Coordination Intervention on Hospital Readmission: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Soc. Work. 2015, 60, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Roberge, J.; Anderson, W.E.; Moore, C.G.; Rossman, W.; Murphy, S.; McCall, S.; Brown, R.; Carpenter, S.; Rissmiller, S.; et al. Aiming to Improve Readmissions Through InteGrated Hospital Transitions (AIRTIGHT): A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, M.; Esteban, E.E.; Hernandez, E.A.; Fleming, M.D.; Safaeinilli, N.; Brewster, A.L. Defining case management success: A qualitative study of case manager perspectives from a large-scale health and social needs support program. BMJ Open Qual. 2022, 11, e001807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitson, A.L.; Rycroft-Malone, J.; Harvey, G.; McCormack, B.; Seers, K.; Titchen, A. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: Theoretical and practical challenges. Implement. Sci. 2008, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, G.; Kitson, A. PARIHS revisited: From heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, G.; Llewellyn, S.; Maniatopoulos, G.; Boyd, A.; Procter, R. Facilitating the implementation of clinical technology in healthcare: What role does a national agency play? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, A.; Ehrenberg, A.; Eldh, A.C.; Graham, I.D.; Gustafsson, K.; Harvey, G.; Hunter, S.; Kitson, A.; Rycroft-Malone, J.; Wallin, L. The use of the PARIHS framework in implementation research and practice-a citation analysis of the literature. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnden, R.; Snowdon, D.A.; Lannin, N.A.; Lynch, E.; Srikanth, V.; Andrew, N.E. Prospective application of theoretical implementation frameworks to improve health care in hospitals-a systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EM, R. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, E.A.; Mudge, A.; Knowles, S.; Kitson, A.L.; Hunter, S.C.; Harvey, G. “There is nothing so practical as a good theory”: A pragmatic guide for selecting theoretical approaches for implementation projects. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Spencer, L. Analyzing Qualitative Data, 1st ed.; Bryman, A., Burgess, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; 22p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria. Department of Health ib. HealthLinks: Chronic Care Evaluation: Summary Report. April 2022 ed. 1 Treasury Place, Melbourne.: Victorian Government. 2022. Available online: https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.health.vic.gov.au%2Fsites%2Fdefault%2Ffiles%2F2022-04%2Fhealthlinks-chronic-care-evaluation-summary-report.docx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Pang, R.K.; Srikanth, V.; Snowdon, D.A.; Weller, C.D.; Berry, B.; Braun, G.; Edwards, I.; McGee, F.; Azzopardi, R.; Andrew, N.E. Targeted care navigation to reduce hospital readmissions in ‘at-risk’ patients. Intern. Med. J. 2023, 53, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, L.; Francis, J.; Islam, R.; O’Connor, D.; Patey, A.; Ivers, N.; Foy, R.; Duncan, E.M.; Colquhoun, H.; Grimshaw, J.M.; et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergen, N.; Labonte, R. “Everything Is Perfect, and We Have No Problems”: Detecting and Limiting Social Desirability Bias in Qualitative Research. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krefting, L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1991, 45, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moullin, J.C.; Dickson, K.S.; Stadnick, N.A.; Albers, B.; Nilsen, P.; Broder-Fingert, S.; Mukasa, B.; Aarons, G.A. Ten recommendations for using implementation frameworks in research and practice. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2020, 1, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstrom, B.; Willman, A.; Svensson, B.; Borglin, G. Perceptions of national guidelines and their (non) implementation in mental healthcare: A deductive and inductive content analysis. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, L.J.; Powell, R.; French, D.P. How can use of the Theoretical Domains Framework be optimized in qualitative research? A rapid systematic review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzo, B.S.; Krziminski Cde, O.; de Oliveira, D.L. The software QSR Nvivo 2.0 in qualitative data analysis: A tool for health and human sciences researches. Rev. Gaucha Enferm. 2003, 24, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners, 1st ed.; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2013; 400p. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, H.P. The origin, evolution, and principles of patient navigation. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2012, 21, 1614–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, B.E.; Richter, K.M.; Youngblood, L.; Cohen, B.A.; Prengler, I.D.; Cheng, D.; Masica, A.L. Reduction of 30-day postdischarge hospital readmission or emergency department (ED) visit rates in high-risk elderly medical patients through delivery of a targeted care bundle. J. Hosp. Med. 2009, 4, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelyn, G.; Laranjo, L.; Schreier, G.; Gallego, B. Predictive performance and impact of algorithms in remote monitoring of chronic conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2021, 156, 104620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwanosike, E.M.; Conway, B.R.; Merchant, H.A.; Hasan, S.S. Potential applications and performance of machine learning techniques and algorithms in clinical practice: A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2022, 159, 104679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, S.; Rolls, D.A.; Boyle, J.; Xie, Y.; Jayasena, R.; Hibbert, M.; Georgeff, M. A risk stratification tool for hospitalisation in Australia using primary care data. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaulding, A.; Kash, B.A.; Johnson, C.E.; Gamm, L. Organizational capacity for change in health care: Development and validation of a scale. Health Care Manage Rev. 2017, 42, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, A.; Peterson, S.; Namusoko, S.; Waiswa, P.; Wallin, L. Knowledge translation in Uganda: A qualitative study of Ugandan midwives’ and managers’ perceived relevance of the sub-elements of the context cornerstone in the PARIHS framework. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnander, E.; McNatt, Z.; Boehmer, K.; Cherlin, E.; Bradley, E.; Curry, L. Changing hospital organisational culture for improved patient outcomes: Developing and implementing the leadership saves lives intervention. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2021, 30, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannion, R.; Davies, H. Understanding organisational culture for healthcare quality improvement. BMJ 2018, 363, k4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggat, S.G.; Dwyer, J. Improving hospital performance: Culture change is not the answer. Healthc. Q. 2005, 8, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Kynoch, K. Implementation of sustainable complex interventions in health care services: The triple C model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlie, E.B.; Shortell, S.M. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: A framework for change. Milbank Q. 2001, 79, 281–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.N.; Guihan, M.; Hogan, T.P.; Smith, B.M.; LaVela, S.L.; Weaver, F.M.; Anaya, H.D.; Evans, C.T. Use of the PARIHS Framework for Retrospective and Prospective Implementation Evaluations. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2017, 14, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitson, A.; Harvey, G.; McCormack, B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: A conceptual framework. Qual. Health Care 1998, 7, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, G.; Loftus-Hills, A.; Rycroft-Malone, J.; Titchen, A.; Kitson, A.; McCormack, B.; Seers, K. Getting evidence into practice: The role and function of facilitation. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 37, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, G.; Kitson, A. Implementing Evidence-Based Practice in Healthcare: A Facilitation Guide, 1st ed.; Harvey, G., Kitson, A., Eds.; Oxon: Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; 240p. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, N.A.; Janda, M.; Stover, A.M.; Alexander, K.E.; Wyld, D.; Mudge, A.; ISOQOL PROMs/PREMs in Clinical Practice Implementation Science Work Group. The utility of the implementation science framework “Integrated Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services” (i-PARIHS) and the facilitator role for introducing patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in a medical oncology outpatient department. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 30, 3063–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme/Subthemes | Description | Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| An algorithm alone is not enough (overarching theme) | Participants believed that the algorithm assisted in directing limited resources to people who needed care. However, they also recognised that the algorithm alone was not enough to support the care navigation model. Targeted care navigation was seen as a community-based model of care and a significant shift from traditional hospital-based models of care. As such, they reported that the successful implementation of targeted care navigation would require substantial resources and leadership from the health service. | “One challenge is identifying the patients who are vulnerable and likely to represent to hospital…an algorithm is a really good start as this helps target the right people and they get the right support. I don’t think the algorithm alone is enough’ but it is a good start.” |

| Health service culture (subtheme) | Participants reported that implementing the targeted care navigation model was challenging because the health service favoured traditional medicalised models of care over holistic multidisciplinary care. Participants reported conflict with this culture, preferring community-based holistic care to hospital-based medicalised care. | “Another one would be the culture and capacity to change. Culturally the organisation was invested in bed-based care and hesitant to pilot innovative projects with a culture of learning around working with these complex individuals.” |

| Leadership (subtheme) | Participants reported that opaque communication between the government and health service and a lack of financial incentive to shift care from the hospital to the community negatively impacted the implementation of the targeted care navigation model. | “We needed higher engagement from the department of health with our health service, and performance meetings and looking at engaging them on this journey first.” |

| Staffing and resources (subtheme) | Participants identified that a key enabler of the targeted care navigation model was the clinician who delivered the care. However, they identified that more clinical staff would ensure that the targeted care navigation model could reach more patients. Participants were also confident that the community health services that existed within the organisation could support people discharging from hospital but identified that better systems were required to facilitate communication and a seamless co-ordination of care between these services. | “In an ideal world we wouldn’t have just one person to provide care navigation and facilitate this.’ ‘Our clinical systems are quite complex and don’t necessarily facilitate good connected care—we need systems to do that.” |

| Patient experience of care (subtheme) | Participants believed that care navigation improved the patient experience of care but were unsure if this led to better outcomes, such as reduced hospital admissions. | “As nice as it was for patients for feeling better, the readmission rate wasn’t reduced. The quality of care improved, the quality of discharge improved but in terms of the outcome we were looking at there was no obvious benefit.” |

| i-PARIHS Construct | Theme/Subtheme(s) | Enablers | Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | Patient experience of care | Perceived improvement in experience and quality of care | Unclear/no benefit for patient outcomes |

| Staff and resources | Algorithm helped to identify and target those most at risk. | ||

| Health service culture | Care navigation model aligns with staff members’ professional values | ||

| Recipients | Patient experience of care | Staff reassured by level of care provided to patients Perception that patients are reassured by level of care received | Belief that some people with chronic disease cannot benefit from the care navigation model |

| Staff and resources | Highly skilled clinician | Lack of staff working on the project | |

| Context (inner): local | Leadership | Commitment from managers to trial care navigation model in the future | Unclear key performance indicators |

| Context (inner): organisational | Staff and resources | Established community health services are sufficient to support patients on discharge from hospital. | Clinical systems are a barrier to coordinating care for people discharging from hospital. |

| Limitations of IT systems to “flag” patients at risk of readmission | |||

| Leadership | Lower organisational priority compared to traditional medicalised models of care | ||

| Risk averseness | |||

| Context (outer): external health system | Leadership | Opaque communication between government and health service | |

| Lack of financial incentive to shift care from hospital-based to community-based services | |||

| Facilitation | Staff and resources | Skilled clinician helped to facilitate implementation of care navigation model | Inadequate staffing to facilitate the implementation of care navigation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pang, R.K.; Andrew, N.E.; Srikanth, V.; Weller, C.D.; Snowdon, D.A. Perceptions of Barriers and Facilitators to a Pilot Implementation of an Algorithm-Supported Care Navigation Model of Care: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3011. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11233011

Pang RK, Andrew NE, Srikanth V, Weller CD, Snowdon DA. Perceptions of Barriers and Facilitators to a Pilot Implementation of an Algorithm-Supported Care Navigation Model of Care: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2023; 11(23):3011. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11233011

Chicago/Turabian StylePang, Rebecca K., Nadine E. Andrew, Velandai Srikanth, Carolina D. Weller, and David A. Snowdon. 2023. "Perceptions of Barriers and Facilitators to a Pilot Implementation of an Algorithm-Supported Care Navigation Model of Care: A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 11, no. 23: 3011. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11233011

APA StylePang, R. K., Andrew, N. E., Srikanth, V., Weller, C. D., & Snowdon, D. A. (2023). Perceptions of Barriers and Facilitators to a Pilot Implementation of an Algorithm-Supported Care Navigation Model of Care: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 11(23), 3011. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11233011