Community Exercise Program Participation and Mental Well-Being in the U.S. Texas–Mexico Border Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

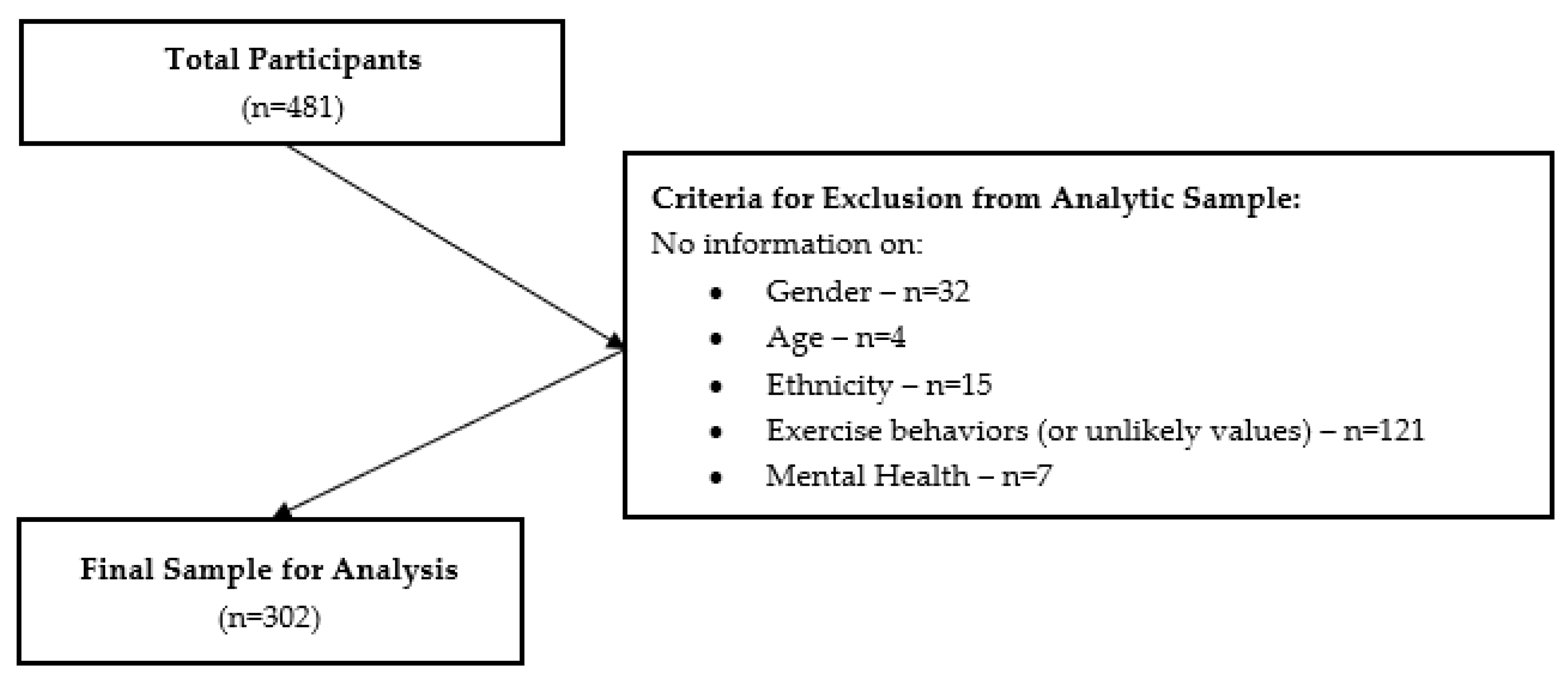

2.2. Sample

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chi-Square Test

3.2. Logistic Regression

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reiner, M.; Niermann, C.; Jekauc, D.; Woll, A. Long-term health benefits of physical activity—A systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleven, L.; Krell-Roesch, J.; Nigg, C.R.; Woll, A. The association between physical activity with incident obesity, coronary heart disease, diabetes and hypertension in adults: A systematic review of longitudinal studies published after 2012. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amesty, S.C. Barriers to Physical Activity in the Hispanic Community. J. Public Health Policy 2003, 24, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista, L.; Reininger, B.; Gay, J.L.; Barroso, C.S.; McCormick, J.B. Perceived barriers to exercise in Hispanic adults by level of activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 2011, 8, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reininger, B.; Wang, J.; Cron, S.; Fisher-Hoch, S.P. Preventive Health Behaviors among Hispanics: Comparing A US-Mexico Border Cohort and National Sample. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. Conf. Proc. 2012, 6, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Heredia, N.I.; Lee, M.; Mitchell-Bennett, L.; Reininger, B.M. Tu Salud ¡Sí Cuenta! Your Health Matters! A Community-wide Campaign in a Hispanic Border Community in Texas. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hovell, M.F.; Mulvihill, M.M.; Buono, M.J.; Liles, S.; Schade, D.H.; Washington, T.A.; Manzano, R.; Sallis, J.F. Culturally tailored aerobic exercise intervention for low-income Latinas. Am. J. Health Promot. 2008, 22, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, D. Culturally tailored education to promote lifestyle change in Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2009, 21, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ickes, M.J.; Sharma, M. A systematic review of physical activity interventions in Hispanic adults. J. Environ. Public Health 2012, 2012, 156435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia, N.I.; Lee, M.; Reininger, B.M. Exposure to a community-wide campaign is associated with physical activity and sedentary behavior among Hispanic adults on the Texas-Mexico border. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvonen, A.; De Vogli, R.; Stafford, M.; Shipley, M.J.; Marmot, M.G.; Cox, T.; Vahtera, J.; Vaananen, A.; Heponiemi, T.; Singh-Manoux, A.; et al. Social support and the likelihood of maintaining and improving levels of physical activity: The Whitehall II Study. Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 22, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay Smith, G.; Banting, L.; Eime, R.; O’Sullivan, G.; van Uffelen, J.G.Z. The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graupensperger, S.; Gottschall, J.S.; Benson, A.J.; Eys, M.; Hastings, B.; Evans, M.B. Perceptions of groupness during fitness classes positively predict recalled perceptions of exertion, enjoyment, and affective valence: An intensive longitudinal investigation. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2019, 8, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrich, K.; Kurtz, B.; Patterson, M.; Crawford, D.; Barry, A. Incorporating a Sense of Community in a Group Exercise Intervention Facilitates Adherence. Health Behav. Res. 2022, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, M.J.; Yi, S.S.; Bartley, K.F.; Eisenhower, D.L. Perceptions and the role of group exercise among New York City adults, 2010–2011: An examination of interpersonal factors and leisure-time physical activity. Prev. Med. 2015, 72, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, M.; Rees, T.; Polman, R. Social identification, exercise participation, and positive exercise experiences: Evidence from parkrun. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Howard, E.P. Physical Activity and Positive Psychological Well-Being Attributes Among U.S. Latino Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2019, 45, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuch, F.B.; Vancampfort, D. Physical activity, exercise, and mental disorders: It is time to move on. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2021, 43, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.; Figueiredo, D.; Teixeira, L.; Poveda, V.; Paúl, C.; Santos-Silva, A.; Costa, E. Physical inactivity among older adults across Europe based on the SHARE database. Age Ageing 2017, 46, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminen, N.; Reinikainen, J.; Appelqvist-Schmidlechner, K.; Borodulin, K.; Mäki-Opas, T.; Solin, P. Associations of physical activity with positive mental health: A population-based study. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2020, 18, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asztalos, M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Cardon, G. The relationship between physical activity and mental health varies across activity intensity levels and dimensions of mental health among women and men. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, T.; Fortier, M.; Sweet, S.N.; Tomasone, J.R. Physical activity participation and mental health profiles in Canadian medical students: Latent profile analysis using continuous latent profile indicators. Psychol. Health Med. 2021, 26, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felez-Nobrega, M.; Bort-Roig, J.; Ma, R.; Romano, E.; Faires, M.; Stubbs, B.; Stamatakis, E.; Olaya, B.; Haro, J.M.; Smith, L.; et al. Light-intensity physical activity and mental ill health: A systematic review of observational studies in the general population. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, R.; Andrade, F.C.D.; Piedra, L.M.; Tabb, K.M.; Xu, S.; Sarkisian, C. The impact of exercise on depressive symptoms in older Hispanic/Latino adults: Results from the ‘¡Caminemos!’ study. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.L.; Senn, T.E.; Carey, M.P. Longitudinal associations between health behaviors and mental health in low-income adults. Transl. Behav. Med. 2013, 3, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Census Bureau. DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171). 2020. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/about/rdo/summary-files.html (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- US Census Bureau. American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates Subject Tables. 2020. Available online: https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/subject-tables/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Fisher-Hoch, S.P.; Rentfro, A.R.; Salinas, J.J.; Perez, A.; Brown, H.S.; Reininger, B.M.; Restrepo, B.I.; Wilson, J.G.; Hossain, M.M.; Rahbar, M.H.; et al. Socioeconomic status and prevalence of obesity and diabetes in a Mexican American community, Cameron County, Texas, 2004–2007. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2010, 7, A53. [Google Scholar]

- Alzoubi, A.; Abunaser, R.; Khassawneh, A.; Alfaqih, M.; Khasawneh, A.; Abdo, N. The Bidirectional Relationship between Diabetes and Depression: A Literature Review. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2018, 39, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Recommendations to increase physical activity in communities. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 22, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, P.G.; Reininger, B.M.; Mitchell-Bennett, L.A.; Lee, M.; Xu, T.; Davé, A.C.; Park, S.K.; Ochoa-Del Toro, A.G. Evaluating the Dissemination and Implementation of a Community Health Worker-Based Community Wide Campaign to Improve Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Physical Activity among Latinos along the U.S.-Mexico Border. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, G.; Shephard, R.J. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can. J. Appl. Sport Sci. 1985, 10, 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Vidoni, M.L.; Lee, M.; Mitchell-Bennett, L.; Reininger, B.M. Home Visit Intervention Promotes Lifestyle Changes: Results of an RCT in Mexican Americans. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piercy, K.L.; Troiano, R.P.; Ballard, R.M.; Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Galuska, D.A.; George, S.M.; Olson, R.D. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018, 320, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Social Well-Being. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1998, 61, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, S.M.; Westerhof, G.J.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; ten Klooster, P.M.; Keyes, C.L. Evaluating the psychometric properties of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF). J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 67, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, G.; Torres, M.; Pedrals, N.; Padilla, O.; Rigotti, A.; Bitran, M. Validation of a Spanish Version of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form Questionnaire. Psicothema 2017, 29, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Vassar, M.; Wayant, C. On reporting and interpreting statistical significance and p values in medical research. BMJ Evid.-Based Med. 2021, 26, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Leo, G.; Sardanelli, F. Statistical significance: P value, 0.05 threshold, and applications to radiomics—Reasons for a conservative approach. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2020, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans: Be Active, Healthy, and Happy! 2008. Available online: www.health.gov/paguidelines (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Rizvi, S.; Khan, A.M. Physical Activity and Its Association with Depression in the Diabetic Hispanic Population. Cureus 2019, 11, e4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, K.; Stojanovska, L.; Polenakovic, M.; Bosevski, M.; Apostolopoulos, V. Exercise and mental health. Maturitas 2017, 106, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Park, Y.S.; Allegrante, J.P.; Marks, R.; Ok, H.; Ok Cho, K.; Garber, C.E. Relationship between physical activity and general mental health. Prev. Med. 2012, 55, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füzéki, E.; Engeroff, T.; Banzer, W. Health Benefits of Light-Intensity Physical Activity: A Systematic Review of Accelerometer Data of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1769–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loprinzi, P.D. Light-Intensity Physical Activity and All-Cause Mortality. Am. J. Health Promot. 2017, 31, 340–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, P.W.; Steptoe, A.; Liao, Y.; Sun, W.J.; Chen, L.J. Prospective relationship between objectively measured light physical activity and depressive symptoms in later life. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 33, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamer, M.; Stamatakis, E.; Steptoe, A. Dose-response relationship between physical activity and mental health: The Scottish Health Survey. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 1111–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Class | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age Category | 18–29 | 28 (9.3) |

| 30–39 | 58 (19.2) | |

| 40–49 | 77 (25.5) | |

| 50–59 | 74 (24.5) | |

| 60+ | 65 (21.5) | |

| Sex | M | 26 (8.6) |

| F | 276 (91.4) | |

| Preferred Language | English | 161 (53.3) |

| Spanish | 141 (46.7) | |

| Year | 2018 | 149 (49.3) |

| 2019 | 153 (50.7) | |

| Insurance Status | No | 141 (48.0) |

| Yes | 153 (52.0) | |

| Employment Status | Unemployed (all reasons) | 151 (52.8) |

| Employed | 135 (47.2) | |

| Self-Reported Health Status | Poor/Fair/Not Sure | 83 (28.2) |

| Good | 129 (43.7) | |

| Very Good | 50 (17.0) | |

| Excellent | 33 (11.2) |

| Variable | Class | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity Intensity Level 1 (mild, moderate, strenuous) | Sedentary/Low (did not meet recommendations) | 42 (13.9) |

| Mild/Mod/Strenuous (met recommendations) | 260 (86.1) | |

| Physical Activity Intensity Level 2 (moderate, strenuous) | Sedentary/Low (did not meet recommendations) | 61 (20.2) |

| Mod/Strenuous (met recommendations) | 241 (79.8) | |

| Time in Class Attendance | <1 to several times a month or my first week | 59 (19.9) |

| At least once weekly to multiple times per week | 238 (80.1) | |

| MHC-SF Diagnosis of Mental Well-Being | Languishing/Moderate | 75 (24.8) |

| Flourishing | 227 (75.2) |

| Mental Well-Being | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Languishing and Moderate n (%) | Flourishing n (%) | χ2 p-Value | |

| Frequency Attending Community Exercise Class | 0.0532 | ||

| None to several times a month or first time | 20 (27.8) | 39 (17.3) | |

| One to multiple times a week | 52 (72.2) | 186 (82.7) | |

| Mild, Moderate, and Strenuous Intensity of Physical Activity (MET-adjusted minutes) | 0.0786 | ||

| Sedentary to Low (did not meet recommendations) | 15 (20.0) | 27 (11.9) | |

| Mild, Moderate, Strenuous (met recommendations) | 60 (80.0) | 200 (88.1) | |

| Moderate and Strenuous Intensity of Physical Activity (MET-adjusted minutes) | 0.2014 | ||

| Sedentary to Low (did not meet recommendations) | 19 (25.3) | 42 (18.5) | |

| Moderate, Strenuous (met recommendations) | 56 (74.7) | 185 (81.5) | |

| Variable | Class | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Category | 60+ vs. <60 | 2.40 (1.12, 5.13) | 0.0237 |

| Sex | Male vs. Female | 0.59 (0.25, 1.39) | 0.2310 |

| Insurance | No vs. Yes | 0.75 (0.44, 1.27) | 0.2817 |

| Employment Status | Currently Unemployed vs. Employed | 0.68 (0.4, 1.18) | 0.1738 |

| Self-Reported Health | Good vs. Poor/Fair/Not Sure | 1.51 (0.83, 2.76) | 0.1440 |

| Very Good vs. Poor/Fair/Not Sure | 2.72 (1.13, 6.58) | 0.4798 | |

| Excellent vs. Poor/Fair/Not Sure | 5.18 (1.45, 18.47) | 0.0612 | |

| How Often Do You Attend Class | None to Several Times a Month vs.One to Several Times a Week | 1.83 (0.99, 3.41) | 0.0554 |

| Physical Activity Level | Moderate and Strenuous (met recommendations) vs. Sedentary and Low (did not meet recommendations) | 1.85 (0.93, 3.71) | 0.0818 |

| Physical Activity Level † | Moderate and Strenuous (met recommendations) vs. Sedentary and Low (did not meet recommendations) | 1.50 (0.81, 2.78) | 0.2031 |

| Variable | Class | Physical Activity Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 Mild, Moderate, Strenuous | Model 2 Moderate, Strenuous | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| Age Category | 60+ vs. <60 | 2.21 (0.97, 5.06) | 0.0596 | 2.22 (0.97, 5.1) | 0.0595 |

| Self-Reported Health | Good vs. Poor/Fair/Not Sure | 1.72 (0.9, 3.29) | 0.5062 | 1.7 (0.89, 3.26) | 0.4692 |

| Very Good vs. Poor/Fair/Not Sure | 2.28 (0.91, 5.69) | 0.7382 | 2.28 (0.91, 5.68) | 0.7520 | |

| Excellent vs. Poor/Fair/Not Sure | 4.36 (1.19, 15.93) | 0.1098 | 4.5 (1.23, 16.41) | 0.0974 | |

| How Often Do You Attend Class | At least once weekly to multiple times per week vs. <1 to several times a month or my first week | 1.75 (0.89, 3.44) | 0.1075 | 1.79 (0.91, 3.52) | 0.0904 |

| Physical Activity Level | Moderate and Strenuous (met guidelines) vs. Sedentary and Low (did not meet guidelines) | 2.30 (1.03, 5.12) | 0.0422 | 1.89 (0.92, 3.9) | 0.0848 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ochoa Del-Toro, A.G.; Mitchell-Bennett, L.A.; Machiorlatti, M.; Robledo, C.A.; Davé, A.C.; Lozoya, R.N.; Reininger, B.M. Community Exercise Program Participation and Mental Well-Being in the U.S. Texas–Mexico Border Region. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2946. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11222946

Ochoa Del-Toro AG, Mitchell-Bennett LA, Machiorlatti M, Robledo CA, Davé AC, Lozoya RN, Reininger BM. Community Exercise Program Participation and Mental Well-Being in the U.S. Texas–Mexico Border Region. Healthcare. 2023; 11(22):2946. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11222946

Chicago/Turabian StyleOchoa Del-Toro, Alma G., Lisa A. Mitchell-Bennett, Michael Machiorlatti, Candace A. Robledo, Amanda C. Davé, Rebecca N. Lozoya, and Belinda M. Reininger. 2023. "Community Exercise Program Participation and Mental Well-Being in the U.S. Texas–Mexico Border Region" Healthcare 11, no. 22: 2946. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11222946

APA StyleOchoa Del-Toro, A. G., Mitchell-Bennett, L. A., Machiorlatti, M., Robledo, C. A., Davé, A. C., Lozoya, R. N., & Reininger, B. M. (2023). Community Exercise Program Participation and Mental Well-Being in the U.S. Texas–Mexico Border Region. Healthcare, 11(22), 2946. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11222946