Abstract

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of death from malformations in the first year of life and carries a significant burden to the family when the diagnosis is made in the prenatal period. We recognize the significance of family counseling following a fetal CHD diagnosis. However, we have observed that most research focuses on assessing the emotional state of family members rather than examining the counseling process itself. The objective of this study was to identify and summarize the findings in the literature on family counseling in cases of diagnosis of CHD during pregnancy, demonstrating gaps and suggesting future research on this topic. Eight databases were searched to review the literature on family counseling in cases of CHD diagnosis during pregnancy. A systematic search was conducted from September to October 2022. The descriptors were “congenital heart disease”, “fetal heart”, and “family counseling”. The inclusion criteria were studies on counseling family members who received a diagnosis of CHD in the fetus (family counseling was defined as any health professional who advises mothers and fathers on the diagnosis of CHD during the gestational period), how the news is expressed to family members (including an explanation of CHD and questions about management and prognosis), empirical and qualitative studies, quantitative studies, no publication deadline, and any language. Out of the initial search of 3719 reports, 21 articles were included. Most were cross-sectional (11) and qualitative (9) studies, and all were from developed countries. The findings in the literature address the difficulties in effectively conducting family counseling, the strengths of family counseling to be effective, opportunities to generate effective counseling, and the main challenges in family counseling.

1. Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common cause of congenital malformation in the fetus [1,2] and the leading cause of death from malformations in the first year of life [3,4]. Fetal cardiology has been evolving in recent years thanks to technological advances and more significant learning by professionals involved in this subject. Consequently, there was an increase in the diagnosis of intrauterine CHD [1,2,3,4,5].

It has become more evident that when CHD is diagnosed in a fetus, parents need to be informed in a compassionate manner. This requires good communication skills and an instructive explanation of the normal heart’s structures and the affected heart. This approach has been noted to be more effective in helping parents understand the situation [6,7]. Questions about the impairment of the well-being of the fetus during pregnancy, during labor, and after the birth, the need for surgery, what type of surgery, the timing of surgical correction, life quality, and prognosis of the baby are common in any circumstance in the face of some cardiac alteration detected in the intrauterine period. Talking to parents about CHD in the fetus raises many doubts, and counseling is fundamental for families. We recognize the significance of family counseling following a fetal CHD diagnosis. However, we have observed that most research focuses on assessing the emotional state of family members rather than examining the counseling process itself. Therefore, the objective of this study was to identify and summarize the findings in the literature on family counseling in cases of diagnosis of CHD during pregnancy, demonstrating gaps and suggesting future research.

2. Materials and Methods

As family counseling in cases of CHD diagnosed during pregnancy is a highly relevant and still emerging topic in the literature, the method chosen was the synthesis of the scope review based on the principles reported by Arksey and O’Malley [8], advocated by the Joanna Briggs Institute principles. We followed the scope review checklist of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [9].

This methodology included five steps: identification of the research question, identification of relevant studies, selection of studies, data mapping, and demonstration of results. The protocol for this scoping review was registered in the Open Science Framework on 4 September 2022 (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/7WK45). As a scoping review, it was not necessary to obtain ethical approval.

2.1. Identification of the Research Question

Considering that in the existing literature, the vast majority relates to family counseling after the diagnosis of CHD in children or about the mother’s emotional state, we decided to evaluate the literature regarding the family counseling after the fetal diagnosis of CHD. Therefore, our research question was what do we know from the literature about family counseling after the fetal diagnosis of CHD?

2.2. Identification of Relevant Studies

A systematic search identified the studies carried out during September and October 2022. Six databases were used, Medline, Embase, LILACS, Scielo, Scopus, and Web of Science, in addition to the gray literature: PsycINFO and Google Scholar. A health sciences research librarian contributed to the development of the search strategy. The descriptors used were congenital heart disease, fetal heart, and family counseling (Table 1). All studies were securely transferred to the Rayyan system for analysis.

Table 1.

Descriptors used in each database.

2.3. Selection of Studies

The inclusion criteria for the studies were as follows: counseling of family members diagnosed with CHD in the fetus. Family counseling was defined as any health professional who advises mothers and/or fathers regarding the diagnosis of CHD during pregnancy. The studies should cover how to convey the diagnosis of CHD to family members, including an explanation of CHD, and management and prognosis questions. The studies could be empirical or qualitative, quantitative, with no publication deadline, except for Google Scholar, and in any language.

We excluded articles with incomplete text, book chapters, abstracts from congress annals, editorials, and lectures.

The first screening performed was the exclusion of duplicate articles. Next, we had two reviewers working as a pair, reading the titles and abstracts of all publications, following the eligibility criteria. After this step, the full text was read, thus concluding the last phase of screening of studies. Doubts and disagreements were resolved by consensus and discussion. A third reviewer read the full text when it was necessary. We conducted a thorough search to cross-check articles related to the subject matter.

2.4. Data Mapping

A Microsoft Excel spreadsheet was used to create a data extraction form (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). The data extracted included the authors, year of publication, study location, objectives, methodology, counseling team, and essential study results.

We listed the selected articles in a single table, from 1 to 21, to facilitate understanding and identification of the graphs and figures.

2.5. Results Demonstration

We presented our findings through narratives, tables, and diagrams. The main topics addressed are shown in graphs. The thematic approach was divided into four themes: (1) obstacles to counseling; (2) strengths for effective counseling; (3) opportunities; and (4) challenges for the healthcare services and the health team.

3. Results

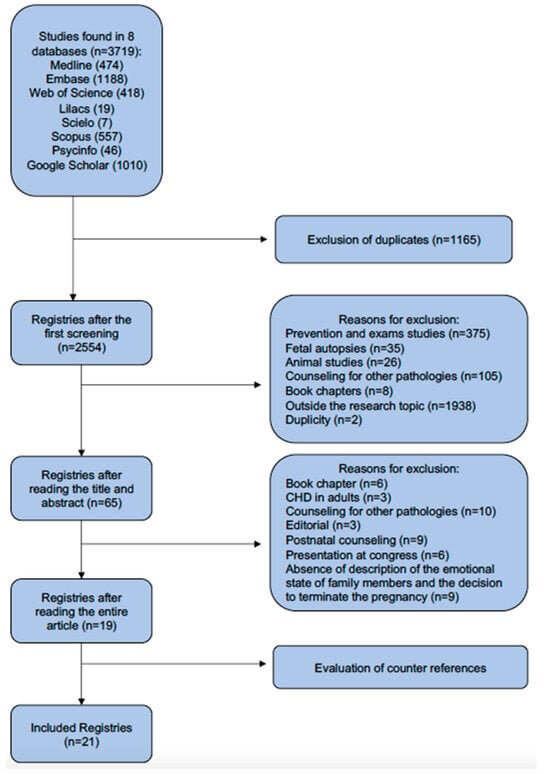

We found 3719 articles in the initial search of the eight databases. Out of the total articles, 1165 were duplicated and 2535 were excluded after analyzing their titles and abstracts. After analyzing for cross-referencing, there were only 21 articles left (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study’s flowchart.

Table 2 presents the data of the 21 eligible articles including authors, year of publication, study location, objectives, methodology, counseling team, and essential study results. For ease of identification, they were numbered from 1 to 21, also used in Table 3.

Table 2.

Main results of the included studies.

Table 3.

The thematic approach of the 21 included studies.

Family counseling in cases of fetal heart disease has been the subject of numerous studies worldwide. The United States of America has produced the largest number of publications on this topic (six articles).

We analyzed 21 articles, of which 19 were published in the last decade. Regarding study design, we found that 11 studies were cross-sectional, 9 used qualitative methods, and only one was a randomized clinical trial, as shown in Table 2.

We categorize our results thematically to present them more effectively in the following way: identifying the obstacles that hinder effective family counseling in cases of fetal heart disease diagnosis, highlighting the strengths that contribute to effective family counseling, outlining the opportunities as well as the challenges that services and healthcare teams face with regard to providing appropriate family counseling in such cases (Table 3).

4. Discussion

We identified 21 studies focused on counseling families dealing with fetal heart disease during pregnancy. These publications, primarily from the last decade, underscore the contemporary significance of this matter within fetal cardiology centers. Our analysis emphasizes the necessity for additional research in specific global regions and underscores the crucial requirement for effective dissemination of knowledge and improved communication strategies for conveying pertinent information to family members (Table 2).

We employed a thematic approach to enhance clarity in presenting our findings and organizing the discussion according to the identified themes. The studies included may appear repeatedly, and the main characteristics were analyzed separately (Table 3).

4.1. Obstacles to Effective Family Counseling in Cases of Diagnosis Heart Disease in the Fetus

Effective family counseling can be challenging when a fetus has been diagnosed with CHD. Obstacles often discussed in the 21 articles included the strength of the doctor–patient relationship, the quality of information transmission to the patient, and the standardization of medical terminology.

The obstacles encountered are interconnected, as a strong doctor–patient relationship depends on good communication between the medical team and the family members, requiring the transmission of information using didactic language. The doctor–patient relationship is a crucial aspect of healthcare. It involves two-way communication and trust between the family and their healthcare provider. A strong relationship can result in better health outcomes. To clarify CHD, it is also necessary to standardize the technical terms used, considering that the diseases can be complex and challenging to understand [3,5,6,10,11,12,13,15,16,18,19,20,26].

The studies highlight several flaws in family counseling services. These include a lack of confidence from the health team when it comes to diagnosing, treating, and predicting outcomes, difficulty in explaining the disease clearly and concisely, no private space for family consultations, no follow-up with the family after diagnosis, a prolonged wait time for the diagnosis to be clarified, and a need for a translator in cases where foreign pregnant women are involved [2,3,6,7,10,12,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,24,25].

4.2. Strengths for Effective Family Counseling

Strengths identified for effective family counseling in the 21 articles were understanding heart disease, how the diagnosis is communicated, and good infrastructure.

It is crucial for family members to understand the disease and its complexities to comprehend survival, treatment, and prognosis. The use of standardized medical terminology is essential in this regard. The medical team must maintain a consistent, accessible, and understandable language that is comprehensible to all family members. To achieve this, the multidisciplinary team should find ways to make the language intelligible. This approach helps to build trust in the team [5].

Continuous family counseling, a prepared multidisciplinary team, and the presence of a pediatric cardiologist are factors in facilitating appropriate family counseling in cases of CHD with an intrauterine diagnosis [11,25,27]. Some studies have emphasized the importance of translation services and the need for private rooms, audiovisual materials, and adequate time for dialogue in the native language [7,11]. Also, the internet offers a valuable opportunity to enhance communication between physicians and parents by collecting feedback from parents across multiple institutions [6,13,17].

Previous studies indicate that implementing a standardized counseling process improved parents’ comprehension of the medical condition [7,9,10]. Visual aids, such as drawings and written information, can help parents recall essential details during a consultation and inform family decisions about pregnancy treatment options [11]. Then, the presentation of information about CHD can influence parental perceptions and decision making regarding survival rates [13].

A good infrastructure is essential for any system to function correctly. Considering our context, we believe that physical and organizational structures and facilities are necessary for effective counseling and the treatment and follow-up of the fetus with CHD [3,14,16,17,23].

4.3. Opportunities for Services and the Healthcare Team in Relation to Appropriate Family Counseling

We recognize the importance of providing better family counseling for pregnant women who receive a fetus diagnosis of CHD and the need for a more compassionate and understanding approach that fosters trust between the medical team and the family [2,3,6,7,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

This trust empowers the family to make informed decisions about the type of treatment and where their child will receive care. A multidisciplinary support network for family members is crucial in strengthening the doctor–patient relationship and ensuring better access to information about the child’s condition [15,16,17,18,19,20,23,26].

The presence of specialists, such as a sociologist, social worker, nurse, psychologist, palliative care specialist, pediatric and fetal cardiologist, maternal-fetal medicine specialist, geneticist, pediatrician, and, in some cases, a pediatric surgeon, can strengthen the multidisciplinary team. The 21 selected studies mentioned these health professionals, highlighting the importance of a specialized group to counsel these pregnant women. Particular emphasis was given to pediatric and fetal cardiologists for their effectiveness in clarifying fetal heart conditions among specialists [6,15,16,17,18,19,20,23].

Humanization and support through a multidisciplinary team can enhance the family’s trust in the medical team and their comprehension of the diagnosis of CHD [3,6,10,11,12,13,14,16,18,19]. As a result, the family becomes more self-assured in making decisions, and this strengthens the bond between parents and children [6,10,13,18,19].

4.4. Challenges for Services and the Health Team in Relation to Adequate Family Counseling in These Cases

The most impactful challenges reported in this scoping review were continuous counseling during pregnancy, a pediatric and fetal cardiologist at the time of a suspected diagnosis, a multidisciplinary team prepared to manage situations of CHD, and didactic and reliable audiovisual resources to help explain heart disease.

Continuing family counseling is crucial, as previously explained. However, it can pose several challenges. One of the significant challenges is the need for a strong bond between the multi-disciplinary team and the family. Another challenge is using complex medical terminologies that may be difficult for family members to comprehend. Additionally, the family members may experience shock and denial after the diagnosis, making it challenging to engage them in counseling. Moreover, the medical team may need help understanding the family’s sociocultural context, further complicating the counseling process [3,13,15,16,18,19,20,21,26].

It was found that having a pediatric and fetal cardiologist present at the time of diagnosis was helpful to improve the understanding of heart disease. However, it can be difficult to reconcile the moment when heart disease is suspected with the presence of a pediatric cardiologist, as it is often suspected during a routine ultrasound examination of pregnant women [2,7,10,12,13,14,17,18,19,20,21,23,25,26].

It is not always possible to have an experienced multi-disciplinary team focused on CHD when the diagnosis is made. Usually, larger hospitals are better equipped to handle such cases. However, many medical services diagnose heart disease before the pregnant woman can reach more specialized centers, which means that the family might not always get the necessary support. The challenge is to provide a multidisciplinary group that can offer sufficient support to the family, even if the diagnosis is made in less affordable services [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,23].

Audiovisual resources can help educate families about heart disease. However, not all media information is reliable, and this is the challenge of the multidisciplinary team, since it is hard to identify which information is most appropriate for each type of heart disease [2,6,7,10,12,18,22,23,24,25].

4.5. Study Limitations

The quality of the selected studies was not assessed, which is not mandatory for this type of review.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review demonstrated that family counseling in cases of fetal diagnosis of CHD is a current topic but not studied adequately. The findings in the literature address the difficulties in effectively conducting family counseling, the strengths of family counseling to be effective, opportunities to generate effective counseling, and the main challenges in family counseling. This scoping review generates essential content for developing a standardized guide covering important points for effective family counseling in cases of CHD in the fetus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A.d.R.A. and S.L.d.M.A.; methodology, L.A.d.R.A., L.T.S.T. and M.B.D.; validation, T.L.L.E. and L.A.d.R.A.; formal analysis, A.L.M.T.N.; investigation, S.L.d.M.A., L.T.S.T. and M.B.D.; resources, L.A.d.R.A.; data curation, S.L.d.M.A., L.T.S.T. and L.I.A.d.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.A.d.R.A. and A.L.M.T.N.; writing—review and editing, L.A.d.R.A. and E.A.J.; visualization, L.I.A.d.C., E.A.J. and T.L.L.E.; supervision, L.A.d.R.A. and E.A.J.; project administration, L.T.S.T.; funding acquisition, L.A.d.R.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Amazonas State Research Support Foundation (FAPEAM), through the Stricto Sensu Graduate Support Program (POSGRAD), by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), and by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), through the Postgraduate Program in Health Sciences and the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Our investigations were carried out following the rules of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, revised in 2013. As this is a review article, it was not necessary to obtain ethics committee approval.

Informed Consent Statement

It was not required, because the study is a review.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Donofrio, M.T.; Moon-Grady, A.J.; Hornberger, L.K.; Copel, J.A.; Sklansky, M.S.; Abuhamad, A.; Cuneo, B.F.; Huhta, J.C.; Jonas, R.A.; Krishnan, A.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Fetal Cardiac Disease: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014, 129, 2183–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacevic, A.; Simmelbauer, A.; Starystach, S.; Elsässer, M.; Sohn, C.; Müller, A.; Bär, S.; Gorenflo, M. Assessment of Needs for Counseling after Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease—A Multidisciplinary Approach. Klin. Padiatr. 2018, 230, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacevic, A.; Elsässer, M.; Fluhr, H.; Müller, A.; Starystach, S.; Bär, S.; Gorenflo, M. Counseling for Fetal Heart Disease—Current Standards and Best Practice. Transl. Pediatr. 2021, 10, 2225–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosano, A.; Botto, L.D.; Botting, B.; Mastroiacovo, P. Infant Mortality and Congenital Anomalies from 1950 to 1994: An International Perspective. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2000, 54, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacevic, A.; Simmelbauer, A.; Starystach, S.; Elsässer, M.; Müller, A.; Bär, S.; Gorenflo, M. Counseling for Prenatal Congenital Heart Disease-Recommendations Based on Empirical Assessment of Counseling Success. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, T.; Marttala, U.M.; Wadensten, B.; Bergman, G.; Mattsson, E. Involvement of Persons with Lived Experience of a Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Defect: An Explorative Study to Gain Insights into Perspectives on Future Research. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2016, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacevic, A.; Wacker-Gussmann, A.; Bär, S.; Elsässer, M.; Motlagh, A.M.; Ostermayer, E.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Ewert, P.; Gorenflo, M.; Starystach, S. Parents’ Perspectives on Counseling for Fetal Heart Disease: What Matters Most? J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Social. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menahem, S.; Grimwade, J. Effective Counselling of Pre-Natal Diagnosis of Serious Heart Disease—An Aid to Maternal Bonding? Diagn. Ther. 2004, 19, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rempel, G.R.; Cender, L.M.; Lynam, M.J.; Sandor, G.G.; Farquharson, D. Parents’ Perspectives on Decision Making after Antenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease. JOGNN J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2004, 33, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton-Kamm, D.; Sklansky, M.; Chang, R.K. How Not to Tell Parents about Their Child’s New Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease: An Internet Survey of 841 Parents. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2014, 35, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, T.; Bergman, G.; Marttala, U.M.; Wadensten, B.; Mattsson, E. Information Following a Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Defect: Experiences among Parents to Prenatally Diagnosed Children. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratt, E.L.; Järvholm, S.; Ekman-Joelsson, B.M.; Mattson, L.Å.; Mellander, M. Parent’s Experiences of Counselling and Their Need for Support Following a Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease—A Qualitative Study in a Swedish Context. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, T.; Marttala, U.M.; Mattsson, E.; Ringnér, A. Experiences and Preferences of Care among Swedish Immigrants Following a Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Defect in the Fetus: A Qualitative Interview Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.J.; Verghese, G.R.; Ferguson, M.E.; Fino, N.F.; Goldberg, D.J.; Owens, S.T.; Pinto, N.; Zyblewski, S.C.; Quartermain, M.D. Counseling Practices for Fetal Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2017, 38, 946–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K. Prenatal Counseling of Fetal Congenital Heart Disease. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, T.; Mattsson, E. Emotional and Cognitive Experiences during the Time of Diagnosis and Decision-Making Following a Prenatal Diagnosis: A Qualitative Study of Males Presented with Congenital Heart Defect in the Fetus Carried by Their Pregnant Partner. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YM, I.; TJ, Y.; IY, Y.; Kim, S.; Jin, J.; Kim, S. The Pregnancy Experience of Korean Mothers with a Prenatal Fetal Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 467. [Google Scholar]

- Bertaud, S.; Lloyd, D.F.A.; Sharland, G.; Razavi, R.; Bluebond-Langner, M. The Impact of Prenatal Counselling on Mothers of Surviving Children with Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome: A Qualitative Interview Study. Health Expect. 2020, 23, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacevic, A.; Bär, S.; Starystach, S.; Simmelbauer, A.; Elsässer, M.; Müller, A.; Motlagh, A.M.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Ostermayer, E.; Ewert, P.; et al. Objective Assessment of Counselling for Fetal Heart Defects: An Interdisciplinary Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, K.W.; Huang, J.H.; Gutshall, K.; Kim, A.; Ronai, C.; Madriago, E.J. Fetal Counseling for Congenital Heart Disease: Is Communication Effective? J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021, 35, 5049–5053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacevic, A.; Bär, S.; Starystach, S.; Elsässer, M.; van der Locht, T.; Motlagh, A.M.; Ostermayer, E.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Ewert, P.; Gorenflo, M.; et al. Fetal Cardiac Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: How Does It Affect Parental Counseling? J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaney, R.K.; Pinto, N.M.; Ozanne, E.M.; Stark, L.A.; Pershing, M.L.; Thorpe, A.; Witteman, H.O.; Thokala, P.; Lambert, L.M.; Hansen, L.M.; et al. Study Protocol for a Randomised Clinical Trial of a Decision Aid and Values Clarification Method for Parents of a Fetus or Neonate Diagnosed with a Life-Threatening Congenital Heart Defect. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e055455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gendler, Y.; Birk, E. Developing a Standardized Approach to Prenatal Counseling Following the Diagnosis of a Complex Congenital Heart Abnormality. Early Hum. Dev. 2021, 163, 105507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.W.; Hammack-Aviran, C.M.; Brelsford, K.M.; Kavanaugh-McHugh, A.; Clayton, E.W. Mapping Parents’ Journey Following Prenatal Diagnosis of CHD: A Qualitative Study. Cardiol. Young 2022, 33, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.G.; Holmes, R.; Martin, R.; Wilde, P.; Soothill, P. Prognosis Following Prenatal Diagnosis of Heart Malformations. Early Hum. Dev. 1998, 52, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).