Stress Management in Healthcare Organizations: The Nigerian Context

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

Theoretical Framework

3. The Concept of Stress and Occupational Stress

3.1. Types of Stress

3.2. Acute Stress

3.3. Episodic Acute Stress

3.4. Chronic Stress

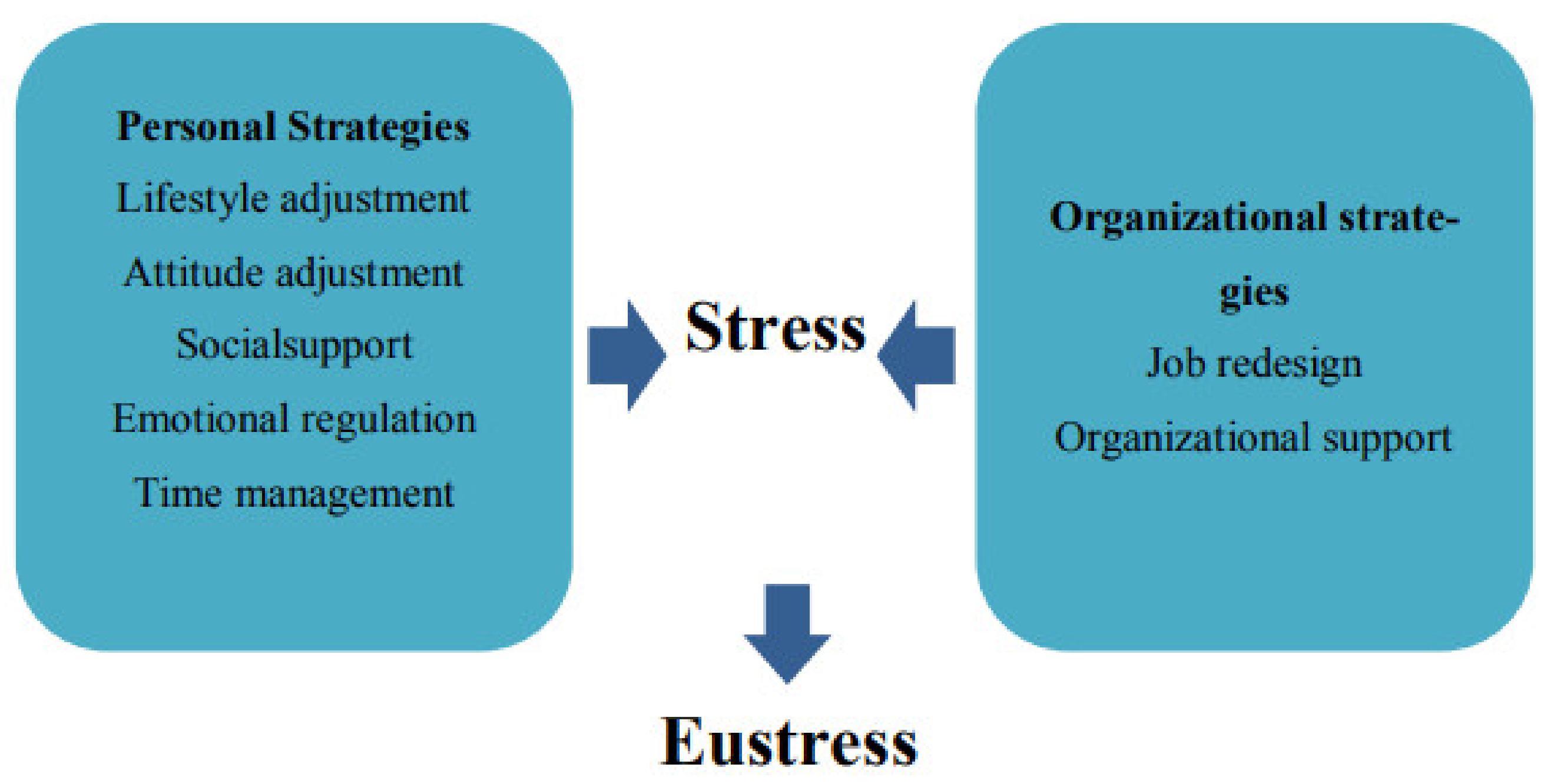

3.5. Stress Management

3.6. Drivers of Stress in Healthcare Organizations

3.7. Long Working Hours

3.8. Ineffective Management

3.9. Personal Life and Interpersonal Relationships

3.10. Organizational Factors

3.11. The Work Environment

3.12. The Stress Management Approach

4. Nigeria’s Healthcare Context

4.1. The Structure of Healthcare Organization in Nigeria

- Primary Healthcare (PHC) Organizations: PHC is a community-based healthcare center that the state and federal governments control. Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) has emphasized that PHC provides less intrusive minor diagnostics and essential medical treatments. PHC serves as an individual, family, or community’s initial point of contact with the national health system [88]. Furthermore, the World Health Organization emphasizes that Nigeria’s primary healthcare system is the most pertinent, distinctive, and important part of the nation’s three-tier healthcare system [89]. Furthermore, due to its proximity to patients compared with other types of healthcare, primary healthcare is better able to meet the local population’s demands for healthcare. Most importantly, Koce et al. [90] pointed out that everyone initially uses the primary healthcare system because it is accessible and designated as the first line of defense in the event of a medical emergency, regardless of social or economic background. Additionally, PHC occupies the lowest position in Nigeria’s healthcare system. A total of 88% of Nigeria’s healthcare facilities, according to Makinde et al. [91], are PHC facilities.

- Secondary Healthcare (SHC) Organizations: “General Hospitals” is another name for this group. The state government oversees s SHC’s business through regulation and oversight. This is due to the fact that healthcare providers have a higher status than PHC and are thought to provide patients with more complex healthcare services [88]. In reality, Balogun [87] noted that PHC providers refer complex and difficult-to-manage medical problems to SHC providers. SHC provides other community health services in addition to general medical, surgical, pediatric, obstetrics, and gynecological care [91]. Private healthcare delivery services are included in Nigeria’s healthcare service delivery category. In contrast to PHC, SHC has considerable staffing and facility capacities.

- Tertiary Healthcare (THC) Organizations: THC includes the top healthcare organizations in Nigeria’s healthcare system. This cadre of the country’s health system delivery includes teaching hospitals, federal medical centers, and other specialized hospitals [85]. More specifically, THC serves as a hub for medical research, as the name suggests. The federal government is responsible for regulating and controlling THC. Around 0.25% of all the country’s medical facilities are in THC. The organizations’ control and management are exclusively reserved for the federal government [88].

4.2. Health System Reform: A Pathway to Improve Stress Management among Healthcare Professionals

4.3. The Nigerian Experience: The Health Workforce Status

4.4. What Has Been Newly Developed in the Field of Stress Management in General?

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

7. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Husso, M.; Notko, M.; Virkki, T.; Holma, J.; Laitila, A.; Siltala, H. Domestic violence interventions in social and health care settings: Challenges of temporary projects and short-term solutions. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 11461–11482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callus, E.; Bassola, B.; Fiolo, V.; Bertoldo, E.G.; Pagliuca, S.; Lusignani, M. Stress reduction techniques for health care providers dealing with severe coronavirus infections (SARS, MERS, and COVID-19): A rapid review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 589698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soon-Yew, J.; Yao, A.; Lai-Kuan, K.; Ismail, A.; Yeo, E. Occupational stress features, emotional intelligence and job satisfaction: An empirical study in private institutions of higher learning. Negotium 2010, 6, 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chiappetta, M.; D’Egidio, V.; Sestili, C.; Cocchiara, R.A.; La Torre, G. Stress management interventions among healthcare workers using mindfulness: A systematic review. Senses Sci. 2018, 5, 517–549. [Google Scholar]

- Salilih, S.Z.; Abajobir, A.A. Work-related stress and associated factors among nurses working in public hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Workplace Health Saf. 2014, 62, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landsbergis, P.A. Occupational stress among health care workers: A test of the job demands-control model. J. Organ. Behav. 1988, 9, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, J.J.; Bassey, P.E.; Ndep, A.O.; Iyam, M.A.; Nwikekii, C.N. Work-related stress among healthcare workers in Ugep, Yakurr Local Government Area, Cross River State, Nigeria: A study of sources, effects, and coping strategies. Int. J. Public Heath Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 1, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, A.; Burgess, C.; Dean, S.; Koutsopoulou, G.Z.; Hugh-Jones, S. How effective are mindfulness-based interventions for reducing stress among healthcare professionals? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stress Health 2017, 33, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girma, B.; Nigussie, J.; Molla, A.; Mareg, M. Occupational stress and associated factors among health care professionals in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omar, A.B. Sources of Work-Stress among Hospital-Staff at the Saudi MOH. JKAU Econ. Adm. 2003, 17, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, R.S.; Segovis, J.; Nelson, T. Work Stress and Coping in the Era of Globalization; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Freshwater, S. 3 Types of Stress and Health Hazards. 2018. Available online: https://spacioustherapy.com/3-types-stress-health-hazards/#:~:text=According%20to%20American%20Psychological%20Association,acute%20stress%2C%20and%20chronic%20stress (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Waters, S. Types of Stress and What You Can Do to Fight Them. 2021. Available online: https://www.betterup.com/blog/types-of-stres (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Chandola, T.; Brunner, E.; Marmot, M. Chronic stress at work and the metabolic syndrome: Prospective study. BMJ 2006, 332, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruotsalainen, J.H.; Verbeek, J.H.; Mariné, A.; Serra, C. Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2016, 134, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, A.; Taieb, O.; Xavier, S.; Baubet, T.; Reyre, A. The benefits of mindfulness-based interventions on burnout among health professionals: A systematic review. Explore 2020, 16, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Tang, S.; Zhou, W. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on work stress and mental health of psychiatric nurses. Psychiatr. Danub. 2018, 30, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onasoga Olayinka, A.; Osamudiamen, O.S.; Ojo, A. Occupational stress management among nurses in selected hospital in Benin city, Edo state, Nigeria. Eur. J. Exp. Biol. 2013, 3, 473–481. [Google Scholar]

- Onigbogi, C.; Banerjee, S. Prevalence of psychosocial stress and its risk factors among health-care workers in Nigeria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Niger. Med. J. 2019, 60, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwokeoma, B.N.; Ede, M.O.; Nwosu, N.; Ikechukwu-Illomuanya, A.; Ogba, F.N.; Ugwoezuonu, A.U.; Nwadike, N. Impact of rational emotive occupational health coaching on work-related stress management among staff of Nigeria police force. Medicine 2019, 98, e16724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebayo, A.; Akinyemi, O.O. “What Are You Really Doing in This Country?”: Emigration Intentions of Nigerian Doctors and Their Policy Implications for Human Resource for Health Management. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2021, 23, 1377–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldometer. Nigerian Population. 2022. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/nigeria-population/ (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory. In Wellbeing: A Complete Reference Guide; Chen, P.Y., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R.A. Humor, laughter and physical health: Methodological issues and research findings. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.R.; LePine, J.A.; Rich, B.L. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B. A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Bakker, A.B., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2010; pp. 102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work Engagement: A Quantitative Review and Test of Its Relations with Task and Contextual Performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Multiple levels in job demands-resources theory: Implications for employee well-being and performance. In Handbook of Well-Being; DEF Publishers: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Agyemang, C.B.; Nyanyofio, J.G.; Gyamfi, G.D. Job stress, sector of work, and shift-work pattern as correlates of worker health and safety: A study of a manufacturing company in Ghana. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, R.; Gupta, R. Effectiveness of meditation programs in empirically reducing stress and amplifying cognitive function, thus boosting individual health status: A narrative overview. Indian J. Health Sci. Biomed. Res. 2021, 14, 181. [Google Scholar]

- Birhanu, M.; Gebrekidan, B.; Tesefa, G.; Tareke, M. Workload determines workplace stress among health professionals working in felege-hiwot referral Hospital, Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. J. Environ. Public Health 2018, 2018, 6286010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govender, I.; Mutunzi, E.; Okonta, H.I. Stress among medical doctors working in public hospitals of the Ngaka Modiri Molema district (Mafikeng health region), North West province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Psychiatry 2012, 18, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyacı, K.; Şensoy, F.; Beydağ, K.D.; Kıyak, M. Stress and stress management in health institutions. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 152, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Yao, A.; Yunus, N.K.Y. Relationship Between Occupational Stress and Job Satisfaction: An Empirical Study in Malaysia. Rom. Econ. J. 2009, 12, 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Ngoc, A.; Le Thi Thanh, X.; Le Thi, H.; Vu Tuan, A.; Nguyen Van, T. Occupational stress among health worker in a National Dermatology Hospital in Vietnam, 2018. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Fujita, S.; Seto, K.; Kitazawa, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Hasegawa, T. Occupational stress among healthcare workers in Japan. Work 2014, 49, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Exposure to Stress: Occupational Hazards in Hospitals; National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- Tsurugano, S.; Nishikitani, M.; Inoue, M.; Yano, E. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on working students: Results from the Labour Force Survey and the student lifestyle survey. J. Occup. Health 2021, 63, e12209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcolm, X. The 3 Different Types of Stress and How Each Can Affect Our Health. 2021. Available online: https://www.flushinghospital.org/newsletter/the-3-different-types-of-stress-and-how-each-can-affect-our-health/ (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Turner, H.A.; Turner, R.J. Understanding variations in exposure to social stress. Health 2005, 9, 209–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahi, M.K. Understanding police stress research. J. Forensic Psychol. Pract. 2002, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, M.F.; Lord, C.; Andrews, J.; Juster, R.P.; Sindi, S.; Arsenault-Lapierre, G.; Lupien, S.J. Chronic stress, cognitive functioning and mental health. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2011, 96, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonstra, R. Reality as the leading cause of stress: Rethinking the impact of chronic stress in nature. Funct. Ecol. 2013, 27, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kema, G.H.; Mirzadi Gohari, A.; Aouini, L.; Gibriel, H.A.; Ware, S.B.; van Den Bosch, F.; Seidl, M.F. Stress and sexual reproduction affect the dynamics of the wheat pathogen effector AvrStb6 and strobilurin resistance. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Trujillo, C.; Ternero, F.; Rodríguez-Ortiz, J.A.; Pavón, J.J.; Montealegre-Meléndez, I.; Arévalo, C.; Torres, Y. Improvement of the balance between a reduced stress shielding and bone ingrowth by bioactive coatings onto porous titanium substrates. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 338, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbonluae, O.O.; Omi-Ujuanbi, G.O.; Akpede, M. Coping strategies for managing occupational stress for improved worker productivity. IFE Psychol. Int. J. 2017, 25, 300–309. [Google Scholar]

- Non, A.L.; León-Pérez, G.; Glass, H.; Kelly, E.; Garrison, N.A. Stress across generations: A qualitative study of stress, coping, and caregiving among Mexican immigrant mothers. Ethn. Health 2019, 24, 378–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, M.K.; Barry, A.E.; Chaney, J.D. Employee stress management: An examination of adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies on employee health. Work 2016, 53, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashifa, K.M. Strategic Measures for Effective Stress Management: An Analysis with Worker in Cotton Mill Industries. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021, 25, 19358–19363. [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik, D.S.; Profit, J.; Morgenthaler, T.I.; Satele, D.V.; Sinsky, C.A.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orji, M.G.; Yakubu, G.N. Effective Stress Management and Employee Productivity in the Nigerian Public Institutions; A Study of National Galary of Arts, Abuja, Nigeria. Bp. Int. Res. Crit. Inst. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2020, 3, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, V.F.; Onasoga, O.A.; Babalola, C. Self-reported occupational stress, environment, working conditions on productivity and organizational impact among nursing staff in Nigerian hospitals. Int. J. Transl. Med. Res. Public Health 2017, 1, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzolo, D.; Zipp, G.P.; Stiskal, D.; Simpkins, S. Stress management strategies for students: The immediate effects of yoga, humor, and reading on stress. J. Coll. Teach. Learn. 2009, 6, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, A.u.R.; Khanzada, S.R.; Khan, K.; Feroz, J.; Hussain, H.M.; Ali, S.Z.; Khawaja, A. Perceived stress among physical therapy students of Isra University. Int. J. Physiother. 2016, 3, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimura, C.; Griffiths, P. The effectiveness of current approaches to workplace stress management in the nursing profession: An evidence based literature review. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 60, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taormina, R.J.; Law, C.M. Approaches to preventing burnout: The effects of personal stress management and organizational socialization. J. Nurs. Manag. 2000, 8, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, H. Stress management and employee performance. Eur. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Stud. 2020, 4, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Avey, J.B.; Luthans, F.; Jensen, S.M. Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifunovic, N.; Jatic, Z.; Kulenovic, A.D. Identification of causes of the occupational stress for health providers at different levels of health care. Med. Arch. 2017, 71, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melaku, L.; Bulcha, G.; Worku, D. Stress, Anxiety, and Depression among Medical Undergraduate Students and Their Coping Strategies. Educ. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9880309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, M.; Kornhaber, R.; Thapa, D.K.; West, S.; Visentin, D. The effectiveness of interventions to improve resilience among health professionals: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 71, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odigie, A. Stress Management for Healthcare Professionals. Degree Thesis. Yrkeshogskolan Arcada. 2016. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/works/25896651 (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Zandi, G.; Shahzad, I.; Farrukh, M.; Kot, S. Supporting role of society and firms to COVID-19 management among medical practitioners. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong CC, Y.; Knee, C.R.; Neighbors, C.; Zvolensky, M.J. Hacking stigma by loving yourself: A mediated-moderation model of self-compassion and stigma. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, C.C. Negative impacts of shiftwork and long work hours. Rehabil. Nurs. 2014, 39, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y. Technology, long work hours, and stress worsen work-life balance in the construction industry. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2018, 10, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.A.; Springmann, M.; Hill, J.; Tilman, D. Multiple health and environmental impacts of foods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 201906908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savery, L.K.; Luks, J.A. Long hours at work: Are they dangerous and do people consent to them? Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2000, 21, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodziewicz, T.L.; Houseman, B.; Hipskind, J.E. Medical error reduction and prevention. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzitheochari, S.; Arber, S. Lack of sleep, work and the long hours culture: Evidence from the UK Time Use Survey. Work Employ. Soc. 2009, 23, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Tan, A.D.; Habermann, T.M.; Sloan, J.A.; Shanafelt, T.D. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA 2009, 302, 1294–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebode, F. Clinical errors and medical negligence. Med. Princ. Pract. 2013, 22, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koinis, A.; Giannou, V.; Drantaki, V.; Angelaina, S.; Stratou, E.; Saridi, M. The impact of Healthcare Workers Job Environment on their Mental-emotional health. Coping strategies: The case of a local General Hospital. Health Psychol. Res. 2015, 3, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S. Causes and management of stress at work. Occup. Environ. Med. 2002, 59, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karyotaki, E.; Cuijpers, P.; Albor, Y.; Alonso, J.; Auerbach, R.P.; Bantjes, J.; Kessler, R.C. Sources of stress and their associations with mental disorders among college students: Results of the world health organization world mental health surveys international college student initiative. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustaka, E.; Constantinidis, T.C. Sources and effects of work-related stress in nursing. Health Sci. J. 2010, 4, 210. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinos, N. Factors influencing stress and job satisfaction of nurses working in psychiatric units: A research review. Health Sci. J. 2008, 2, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, A.U.; Aston, J. A relationship between occupational stress and organisational commitment of it sector’s employees in contrasting economies. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 14, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawaty, K.; Ramly, M.; Ramlawati, R. The effect of work environment, stress, and job satisfaction on employee turnover intention. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kath, L.M.; Stichler, J.F.; Ehrhart, M.G.; Sievers, A. Predictors of nurse manager stress: A dominance analysis of potential work environment stressors. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 1474–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahavandi, A.; Denhardt, R.B.; Denhardt, J.V.; Aristigueta, M.P. Organizational Behavior; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu, G.; Anitha, R. Stress Management Strategies: A New Way to Achieve Success. Asian J. Manag. 2012, 3, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Häfner, A.; Stock, A.; Oberst, V. Decreasing students’ stress through time management training: An intervention study. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2015, 30, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, I.; Dalglish, S.L.; Angell, B.; Sanuade, O.; Abimbola, S.; Adamu, A.L.; Adetifa IM, O.; Colbourn, T.; Ogunlesi, A.O.; Onwujekwe, O.; et al. The Lancet Nigeria Commission: Investing in health and the future of the nation. Lancet 2022, 399, 1155–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.C. Employees’ perception of organizational change: The mediating effects of stress management strategies. Public Pers. Manag. 2009, 38, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welcome, M.O. The Nigerian health care system: Need for integrating adequate medical intelligence and surveillance systems. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2011, 3, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balogun, J.A. The Organizational Structure and Leadership of the Nigerian Healthcare System. In The Nigerian Healthcare System; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 87–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Primary Health Care. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/primaryhealth-care#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- World Health Organization. A Vision for Primary Health Care in the 21st Century: Towards Universal Health Coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals (No. WHO/HIS/SDS/2018.15); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Koce, F.; Randhawa, G.; Ochieng, B. Understanding healthcare self-referral in Nigeria from the service users’ perspective: A qualitative study of Niger state. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonge, S.K. Primary Health Care in Nigeria: An Appraisal of the Effect of Foreign Donations. Afr. J. Health Saf. Environ. 2020, 1, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makinde, O.A.; Sule, A.; Ayankogbe, O.; Boone, D. Distribution of health facilities in Nigeria: Implications and options for universal health coverage. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2018, 33, e1179–e1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, P.A.; Sibbel, R.; Jones, C. Level of health care and services in a tertiary health setting in Nigeria. Niger. J. Paediatr. 2014, 41, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO|Regional Office for Africa. WHO Delivers Critical Health Services to Meet Basic Humanitarian Needs of 1 Million People. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/nigeria/news/who-delivers-critical-health-services-meet-basic-humanitarian-needs-1-million-people (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Green, S. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; Volume S38. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Stress. 21 February 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/stress#:~:text=Stress%20makes%20it%20hard%20for,or%20eat%20more%20than%20usual (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Tips for Healthcare Professionals: Coping with stress and Compassion Fatigue. 2023. Available online: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/SAMHSA_Digital_Download/PEP20-01-01-016_508.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Baumann, H.; Heuel, L.; Bischoff, L.L.; Wollesen, B. mHealth interventions to reduce stress in healthcare workers (fitcor): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2023, 24, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Words |

|---|

| “stress” OR “strain” OR “burnout” OR “tired” OR “mental stress” OR “physical stress” |

| AND |

| “Management” OR “organization” OR “sector” OR “leaders” OR “hospitals” OR “health” “organization” |

| AND |

| “Healthcare” OR “health sector “ OR “pharmacy” OR “health center” OR “primary healthcare organization”OR “secondary healthcare organization” OR “tertiary healthcare organization” OR “services” OR “health workers”OR “health professionals” |

| AND |

| “qualitative study” OR “interview” OR “discussion” OR “focus group” OR “field work” OR “qualitative research”OR “semi-structured” OR “unstructured” OR “structured” OR “informal” OR “in-depth” OR “face-to-face” |

| AND |

| “Nigeria” OR “Lagos” OR “Abuja” OR “Port Harcourt” OR “Ogun” OR “Kaduna” OR “Adamawa” OR “Gombe” OR “Taraba” OR “Yobe” OR “Ekiti” OR “Anambra” OR “Enugu” OR “Oyo” OR “Cross River” OR “Edo” OR “Delta” OR “Benue” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nwobodo, E.P.; Strukcinskiene, B.; Razbadauskas, A.; Grigoliene, R.; Agostinis-Sobrinho, C. Stress Management in Healthcare Organizations: The Nigerian Context. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2815. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212815

Nwobodo EP, Strukcinskiene B, Razbadauskas A, Grigoliene R, Agostinis-Sobrinho C. Stress Management in Healthcare Organizations: The Nigerian Context. Healthcare. 2023; 11(21):2815. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212815

Chicago/Turabian StyleNwobodo, Ezinne Precious, Birute Strukcinskiene, Arturas Razbadauskas, Rasa Grigoliene, and Cesar Agostinis-Sobrinho. 2023. "Stress Management in Healthcare Organizations: The Nigerian Context" Healthcare 11, no. 21: 2815. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212815

APA StyleNwobodo, E. P., Strukcinskiene, B., Razbadauskas, A., Grigoliene, R., & Agostinis-Sobrinho, C. (2023). Stress Management in Healthcare Organizations: The Nigerian Context. Healthcare, 11(21), 2815. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11212815