Fathers’ Educational Needs Assessment in Relation to Their Participation in Perinatal Care: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

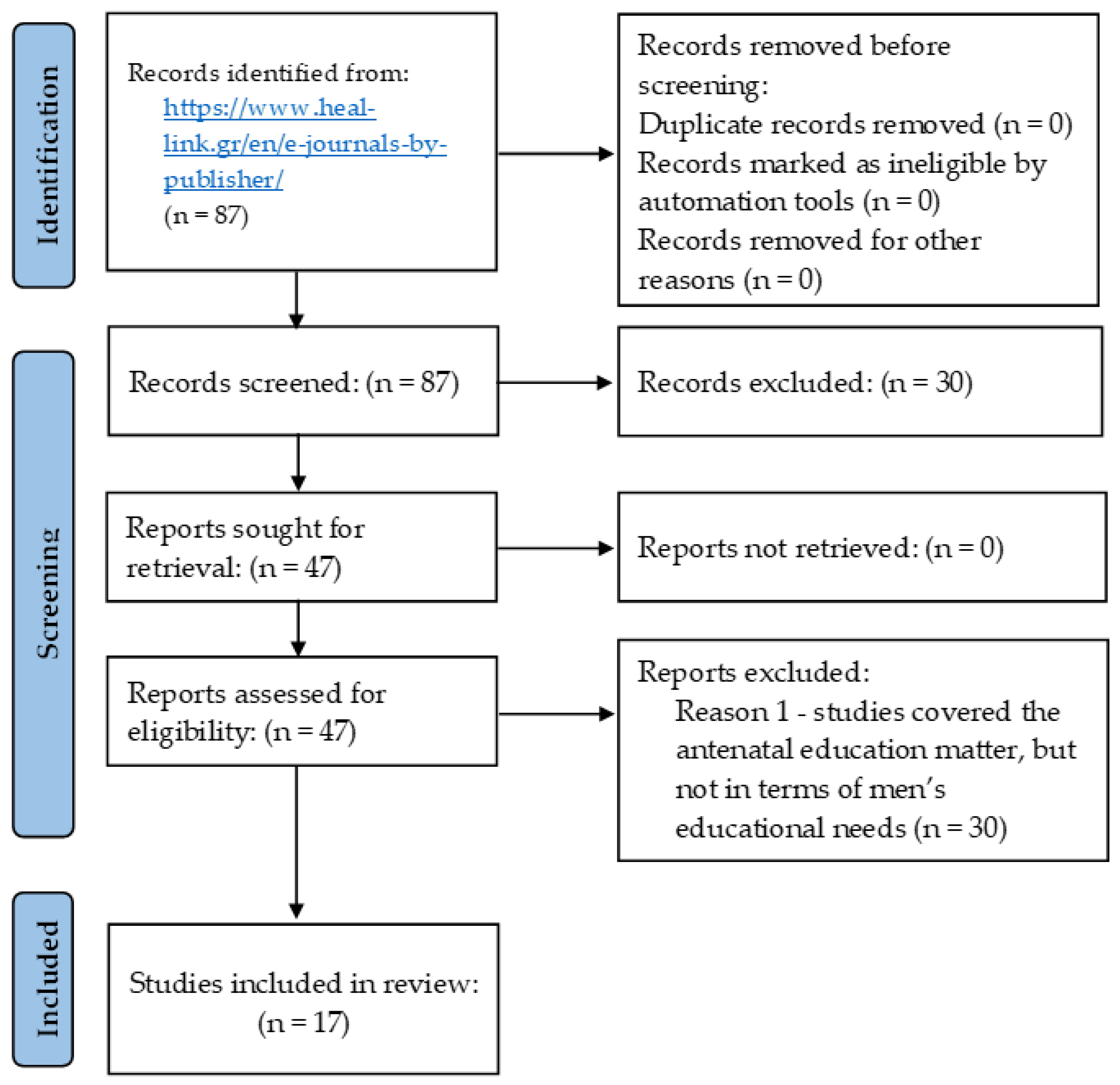

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nation Population Fund (UNFPA). Interactive Center. Enhancing Men’s Roles and Responsibilities in Family Life. A New Role for Men. 2009. Available online: http://www.unfpa.org/intercenter/role4men/enhancin.htm. (accessed on 5 September 2009).

- Greene, M.; Mehta, M.; Pulerwitz, J.; Wulf, D.; Banjole, A.; Susheela, S. Involving Men in Reproductive Health: Contributions to Development; Background Paper to the Report Public Choices, Private Decisions: Sexual and Reproductive Health and the Millennium Development Goals; UN Millennium Project: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Maternal Mortality Fact Sheet No 348. 2016. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs348/en/ (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Simbar, M.; Nahidi, F.; Ramezani Tehrani, F.; Ramezankhani, A.; Akbarzadeh, A. Father’s educational needs for participation in pregnancy care. Payesh 2012, 11, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Simbar, M.; Tehrani, F.; Hashemi, Z. Reproductive health knowledge, attitudes and practices of Iranian college students. East Mediterr Health 2005, 11, 888–897. [Google Scholar]

- Galanz, C.; Louis, F.; Reimer, B. Health Behavior and Health Education; Khoshbin Publication: Tehran, Iran, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Programming for Male Involvement in Reproductive Health; Report of the Meeting of WHO Regional Advisers in Reproductive Health; WHO/PAHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nasiri, S.; Vaseghi, F.; Moravvaji, S.A.; Babaei, M. Men’s educational needs assessment in terms of their participation in prenatal, childbirth, and postnatal care. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2019, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastable, S.B. Nurse an Educator: Principles of Teaching and Learning for Nursing Practice, 2nd ed.; Jones and Burtllett Publication: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, P.; Omid, A.; Yamani, N. Needs assessment of the public health curriculum based on the first-level health services package in Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J. Learning needs assessment: Assessing the need. BMJ 2002, 324, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alio, A.P.; Salihu, H.M.; Kornosky, J.L.; Richman, A.M.; Marty, P.J. Feto-infant health and survival: Does paternal involvement matter? Matern. Child Health J. 2010, 14, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yargawa, J.; Leonardi-Bee, J. Male involvement and maternal health outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, D. Empowering Communities to Make Pregnancy Safer: An Intervention in Rural Andhra Pradesh; Population Council: New Delhi, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Turan, J.M.; Tesfagiorghis, M.; Polan, M.L. Evaluation of a community intervention for promotion of safe motherhood in Eritrea. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2011, 56, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, S.; Malone, M.; Sandall, J.; Bick, D. A qualitative exploratory study of UK first-time fathers’ experiences, mental health and wellbeing needs during their transition to fatherhood. BMJ 2019, 9, e030792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckström, C.; Thorstensson, S.; Mårtensson, L.B.; Grimming, R.; Nyblin, Y.; Golsäter, M. ‘To be able to support her, I must feel calm and safe’: Pregnant women’s partners perceptions of professional support during pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, M.; Rudman, A.; Waldenström, U.; Kieler, H. Fear of childbirth in expectant fathers, subsequent childbirth experience and impact of antenatal education: Subanalysis of results from a randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2013, 92, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chikalipo, M.C.; Chirwa, E.M.; Muula, A.S. Exploring antenatal education content for couples in Blantyre, Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diemer, G.A. Expectant fathers: Influence of perinatal education 14. on stress, coping, and spousal relations. Res. Nurs. Health 1997, 20, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, K.; Beeckman, D.; Van Hecke, A.; Delbaere, I.; Verhaeghe, S. Needs of fathers during labour and childbirth: A cross-sectional study. Women Birth 2017, 30, e188–e197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erlandsson, K.; Häggström-Nordin, E. Prenatal parental education from the perspective of fathers with experience as primary caregiver immediately following birth: A phenomenographic study. J. Perinat. Educ. 2010, 19, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayers, A.; Hambidge, S.; Bryant, O.; Arden-Close, E. Supporting women who develop poor postnatal mental health: What support do fathers receive to support their partner and their own mental health? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehran, N.; Hajian, S.; Simbar, M.; Alavi Majd, H. Spouse’s participation in perinatal care: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, P.D.; Rominov, H. Fathers’ Worries During Pregnancy: A Qualitative Content Analysis of Reddit. J. Perinatal. Educ. 2017, 26, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinicke, K. First-Time Fathers’ Attitudes Towards, and Experiences With, Parenting Courses in Denmark. Am. J. Men’s Health 2020, 14, 1557988320957546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, F.; Majidi, M.; Shobeiri, F.; Parsa, P.; Roshanaei, G. Knowledge and Attitude of Men Towards Participation in Their Wives’ Perinatal Care. Int. J. Women’s Health Reprod. Sci. 2018, 6, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, B.; Almeida, C.; Santos, J.; Lago, E.; Oliveira, J.; Cruz, T.; Lima, S.; Camargo, E. Meanings Assigned by Primary Care Professionals to Male Prenatal Care: A Qualitative Study. Open Nurs. J. 2021, 15, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohotoa, J.; Maycock, B.; Hauck, Y.L.; Dhaliwal, S.; Howat, P.; Burns, S.; Binns, C.W. Can father inclusive practice reduce paternal postnatal anxiety? A repeated measures cohort study using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012, 31, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, J.M.; Nalbant, H.; Bulut, A.; Sahip, Y. Including expectant fathers in antenatal education programmes in Istanbul, Turkey. Reprod Health Matters 2001, 9, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, E.S.; Ashwill, J.W.; Murray, S.S.; James, S.R.; Gorrie, T.M.; Droske, S.C. Maternal–Child Nursing; W. B. Saunders Co.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mullick, S.; Kunene, B.; Wanjiru, M. Involving Men in Maternity Care: Health Service Delivery Issues. 2005. Available online: http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/frontiers/journals/Agenda_Mullick05.pdf. (accessed on 15 January 2006).

- Carter, M. Husbands and maternal health matters in rural Guatemala: Wives’ reports on their spouses’ involvement in pregnancy and birth. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 55, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullany, B.C.; Hindin, M.J.; Becker, S. Can Women’s autonomy impede male involvement in pregnancy health in Katmandu. Nepal Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 1993–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushi, D.; Mpembeni, R.; Jahn, A. Effectiveness of community based safe motherhood promoters in improving the utilization of obstetric care. The case of Mtwara Rural District in Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.W.; Speizer, I. Salvadoran fathers’ attendance at prenatal care, delivery, and postpartum care. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 2005, 18, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfberg, A.J.; Michels, K.B.; Shields, W.; O’Campo, P.; Bronner, Y.; Bienstock, J. Dads as breastfeeding advocates: Results from a randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 191, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, J.M.; Say, L. Community-based antenatal education in Istanbul, Turkey: Effects on health behaviours. Health Policy Plan. 2003, 18, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Fatherhood and Health Outcomes in Europe; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gibore, N.S.; Bali, T. Community perspectives: An exploration of potential barriers to men’s involvement in maternity care in a central Tanzanian community. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, P.D.; Rominov, H.; Milne, L.; Giallo, R.; Whelan, T. Partners to parents: Development of an on-line intervention for enhancing partner support and preventing perinatal depression and anxiety. Adv. Mental Health Res. 2016, 15, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildingsson, I.; Johansson, M.; Fenwick, J.; Haines, H.; Rubertsson, C. Childbirth fear in expectant fathers: Findings from a regional Swedish cohort study. Midwifery 2014, 30, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, R.J.; Matthey, S.; Marley, C.G. Addressing depression and anxiety among new fathers. Med. J. Aust. 2006, 185, 461–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, A.S.; Barlow, J.; Redshaw, M.A. Birth and Beyond: A Review of the Evidence about Antenatal Education. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258369289_Birth_and_beyond_a_review_of_the_evidence_about_antenatal_education (accessed on 31 January 2009).

- Ekström, A.; Arvidsson, K.; Falkenström, M.; Thorstensson, S. Fathers’ feelings and experiences during pregnancy and childbirth: A qualitative study. J. Nur. Care 2013, 2, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, E.K.; Fridlund, B.; Kvist, L.J.; Dykes, A.K. Fathers’ sense of security during the first postnatal week—A qualitative interview study in Sweden. Midwifery 2012, 28, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Teubert, D. A meta-analytic study of couple interventions during the transition to parenthood. Fam. Relat. 2010, 59, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, M.E.; Levack, A. Synchronizing Gender Strategies. A Cooperative Model for Improving Reproductive Health and Transforming Gender Relations. For the Interagency Gender Working Group (IGWG). 2010. Available online: https://www.igwg.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/synchronizing-gender-strategies.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

| Reference | Aim | Country | Year | Study Design | Measures | Final Sample Size | Outcomes/Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baldwin, S.; et al. (2019). [16] | To explore men’s own perceived needs and how they would like to be supported during and beyond their partner’s pregnancy. | United Kingdom | 2019 | Maximum variation sampling | Face-to-face in-depth interviews | 21 men | The interviewed men desired to be appropriately informed about labor and their role as birth partners. A greater understanding of the physical and emotional demands of parenthood during the early days and weeks after birth was expressed. |

| Bäckström, C.; et al. (2017). [17] | To explore pregnant women’s partners’ perceptions of professional support during pregnancy | Sweden | 2017 | Qualitative research design | Semi-structured interviews | 14 men | A positive impact on the couple’s relationship was perceived by men during pregnancy as a result of professional support. Furthermore, they believed that lack of professional support would contribute to feelings of unimportance, potentially affecting mothers and babies negatively. |

| Bergström, M.; et al. (2013). [18] | To explore if antenatal fear of childbirth in men affects their experience of the birth event and if this experience is associated with the type of childbirth preparation. | Sweden | 2013 | Randomized controlled multicenter trial on antenatal education | Wijma Delivery Expectancy Questionnaire, W-DEQ A (Wijma, Wijma, & Zar, 1998) | 762 men | The chance of experiencing childbirth as frightening is higher for men suffering from antenatal FOC (Fear Of Childbirth). In addition to childbirth preparation, antenatal education may help men to have a more positive experience of childbirth. |

| Chikalipo, M.C.; Chirwa, E.M.; Muula, A.S. (2018). [19] | To gain a deeper understanding of the education content for couples during antenatal education sessions in Malawi. | Republic of Malawi | 2018 | Exploratory cross-sectional descriptive study (qualitative approach) | In-depth interviews | 34 women, 35 men, 7 midwives & 13 Key informants | Men and women expressed relatively similar needs referring to antenatal education, such as pregnant woman care, childbirth, child care, and family planning. Furthermore, sex and men’s roles during the perinatal periods, prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission, and family life were the topics desired by men, in comparison to birth preparedness was more desired by women. |

| Diemer, G.A. (1997). [20] | To compare the effects of father-focused discussion in perinatal classes with traditional childbirth classes on expectant fathers’ stress/psychological symptom status, coping strategies, social support, and spousal relations. | USA, Madison | 1997 | Quasi- experimental study | 1. Brief Symptom Inventory, BSI (Deroogatis & Spencer, 1982) 2. Coping Measure Scale, CMS (Lazarus & Folkman 1984) 3. Social Network Support Scale, SNSS (Fischer, 1982) 4. Supportive Behavior Questionnaire, SBQ (Wapner, 1976, adapted by Diemer, 1981) 5. Conflict Tactics Scale, CTS (Straus, 1979) | 108 couples | Antenatal education for fathers can positively influence men’s coping behavior and relationships with their partners during pregnancy. Expectant fathers may benefit from small-group discussions so as to express their concerns and feelings and establish relationships with each other, which would positively affect the relationship between the couple. |

| Eggermont, K.; et al. (2017). [21] | To identify fathers’ needs during the labor and childbirth process. | Belgium | 2017 | Multistage consensus method | The questionnaire designed for this study consisted of six parts: (1) preparation for childbirth, (2) general information, (3) support from the midwives, (4) experiences of labor and childbirth, (5) needs during labor and childbirth, and (6) demographic characteristics | 72 men | Information needs were more important to men than experience or involvement. Apparently, the need for information also implies a degree of involvement. A separation in needs clearly indicates that formal information needs are more relevant than being involved in the childbearing process. |

| Erlandsson, K.; Häggström-Nordin, E. (2010). [22] | To capture fathers’ conceptions of parental education topics, illuminated by their experiences as primary caregivers of their child immediately following birth. | Sweden | 2010 | Phenomeno-graphic method | In-depth interviews | 15 men | Fathers should be involved in parental education in order to achieve parity with mothers in their role as parents. Among the most important topics discussed are the mother-infant separation effects on mothers, fathers, and newborns. |

| Mayers, A.; et al. (2020). [23] | To investigate fathers’ experience of support provided to fathers. | United Kingdom | 2020 | Qualitative study | Online Questionnaire, with open questions regarding the father’s emotional well-being and the offered support | 25 men | Fathers perceived a lack of healthcare education and training regarding their educational needs in relation to perinatal care. In this study, they reflected that earlier intervention might have a beneficial impact on their mental health in the longer term. |

| Mehran, N.; et al. (2020). [24] | To explain the concept of spouse participation in perinatal care. | Iran | 2020 | Qualitative study | Semi-structured in-depth interviews | 7 men | Empathy and accountability were the most important aspects of men’s involvement in perinatal care. As a general result, the concept of men’s participation in perinatal care has been defined as a set of accountable behaviors towards their partners based on emotional and cognitive responses, position management, support, and compassion. Improvement of the family function and mother and baby health is the favorable consequences. |

| Nasiri, S.; et al. (2019). [8] | To identify men’s educational needs for participation in prenatal, childbirth, and postnatal care. | Iran | 2019 | Descriptive cross-sectional study (cluster sampling) | Questionnaire designed based on Mortazavi and Simbar’s studies that included demographic characteristics of the subjects, their educational needs in terms of the content of the training program, the training method, the trainer, time and place of training | 280 men | Nutrition, sexual health, and warning signs during pregnancy were the most important educational needs articulated by men, preferably receiving information from a physician. According to them, the best educational place is home, the health center, and the hospital, respectively; evenings hours and holidays seemed to be chosen as the best time for it. |

| Pilkington, P.D.; Rominov, H. (2017). [25] | To obtain insights into fathers’ worries during pregnancy by analyzing the content of posts on the Internet forum Reddit. | Online network of communities | 2017 | Qualitative Content Analysis of Reddit | Analyzing the content of posts on the Internet forum Reddit | 426 unique users submitted the 535 posts in the final data set | The findings provide insights into the type of worries that some fathers experience during pregnancy, which can inform the development of father-specific resources and perinatal education, such as perinatal loss, maternal well-being, father role, feeling unprepared, genetic or chromosomal abnormalities, gender of the infant, childbirth, the well-being of infant following birth, appointments and financial pressure. |

| Reinicke, K. (2020). [26] | To explore the extent to which parenting courses attended by both the mother and the father constitute an appealing institutional service for first-time fathers and whether they find them useful in tackling the challenges they face during pregnancy and after birth. | Denmark | Qualitative study | Individual semi-structured interviews, group interview, and observations | 10 men | Fathers who participated in the 1-year course and received support, inspiration, and information, experienced competence improvement regarding their parenting roles, as well as a sense of responsibility and awareness of their role as a father. | |

| Simbar, M.; et al. (2012). [4] | To assess the educational needs of men for their participation in perinatal care. | Iran | 2011 | Quota sampling method | Focus group discussions | 24 women & 22 men | More than 95% of participants agreed with perinatal care education for men, and the content most required was “signs of risks during the perinatal period” and “mothers’ nutrition”. The majority of participants preferred the face-to-face couples’ counseling method, at home as the best place, and evenings and weekends as the best time. |

| Soltani, F.; et al. (2018). [27] | To investigate men’s knowledge and attitude about participation in their wives’ perinatal care | Iran | 2018 | Descriptive cross-sectional study | “Men’s knowledge and attitudes about participation in perinatal care” questionnaire, designed by the research team | 300 men | Among various aspects of perinatal care, the highest number of men appreciate a good level of knowledge related to the field of delivery and breastfeeding. |

| Sousa, B.; et al. (2021). [28] | To identify the meanings assigned by primary health care professionals to male prenatal care. | Brazil | 2021 | Descriptive study (qualitative approach) | Semi-structured interviews | 19 primary health care professionals | The role of fathers in the pregnancy and delivery procedures can highly benefit this process, as their presence and support promote the safety of mothers and babies, decreasing preventable risks during pregnancy and establishing an early bond between father and child. |

| Tohotoa, J.; et al. (2012). [29] | To identify the impact of a father-inclusive intervention on perinatal anxiety and depression | Western Australia | 2012 | Repeated measures cohort study | A baseline questionnaire that included demographic data of age, marital status, nationality, income, and educational level, plus the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | 533 men (289 in the intervention group & 244 in the control group) | Improved antenatal education to meet the needs of both mothers and fathers and early awareness and intervention may limit the negative impact of perinatal anxiety and depression on parenting attitudes and behavior and increase coping skills. |

| Turan, J.M.; et al. (2001). [30] | To investigate methods for including men in antenatal education in Istanbul, Turkey. | Turkey | 2001 | Formative study (qualitative research methods) | Three studies investigating methods | 30 men & 38 women | Antenatal education can have positive effects on reproductive health knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. In the community-based program, positive effects were also seen in the areas of infant health and feeding, spousal communication, and support. It seems likely that the more intensive, continuous, and ‘support group’ nature of the community-based program for expectant fathers, compared to the clinic-based program, may be a more successful method for involving men. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palioura, Z.; Sarantaki, A.; Antoniou, E.; Iliadou, M.; Dagla, M. Fathers’ Educational Needs Assessment in Relation to Their Participation in Perinatal Care: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11020200

Palioura Z, Sarantaki A, Antoniou E, Iliadou M, Dagla M. Fathers’ Educational Needs Assessment in Relation to Their Participation in Perinatal Care: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2023; 11(2):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11020200

Chicago/Turabian StylePalioura, Zoi, Antigoni Sarantaki, Evangelia Antoniou, Maria Iliadou, and Maria Dagla. 2023. "Fathers’ Educational Needs Assessment in Relation to Their Participation in Perinatal Care: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 11, no. 2: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11020200

APA StylePalioura, Z., Sarantaki, A., Antoniou, E., Iliadou, M., & Dagla, M. (2023). Fathers’ Educational Needs Assessment in Relation to Their Participation in Perinatal Care: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 11(2), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11020200