Determinants of Communication Failure in Intubated Critically Ill Patients: A Qualitative Phenomenological Study from the Perspective of Critical Care Nurses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants Recruitment

2.3. Settings

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Trustworthiness

3. Findings

3.1. Patient-Related Determinants

3.1.1. The Patient’s Physical and Cognitive Functionality

3.1.2. Patient’s Relational and Communicative Style

3.1.3. Personal Circumstances

3.2. Context Determinants

3.2.1. Family Presence

3.2.2. ICU Inherent Characteristics: Noise, Lighting and High Technology Care

3.2.3. Time Organisation, Workload and Continuity of Care

3.2.4. Availability and Features of the Communication Aids

3.2.5. Features of the Message: Kind of Message and Output Mode

3.2.6. Communication Situations

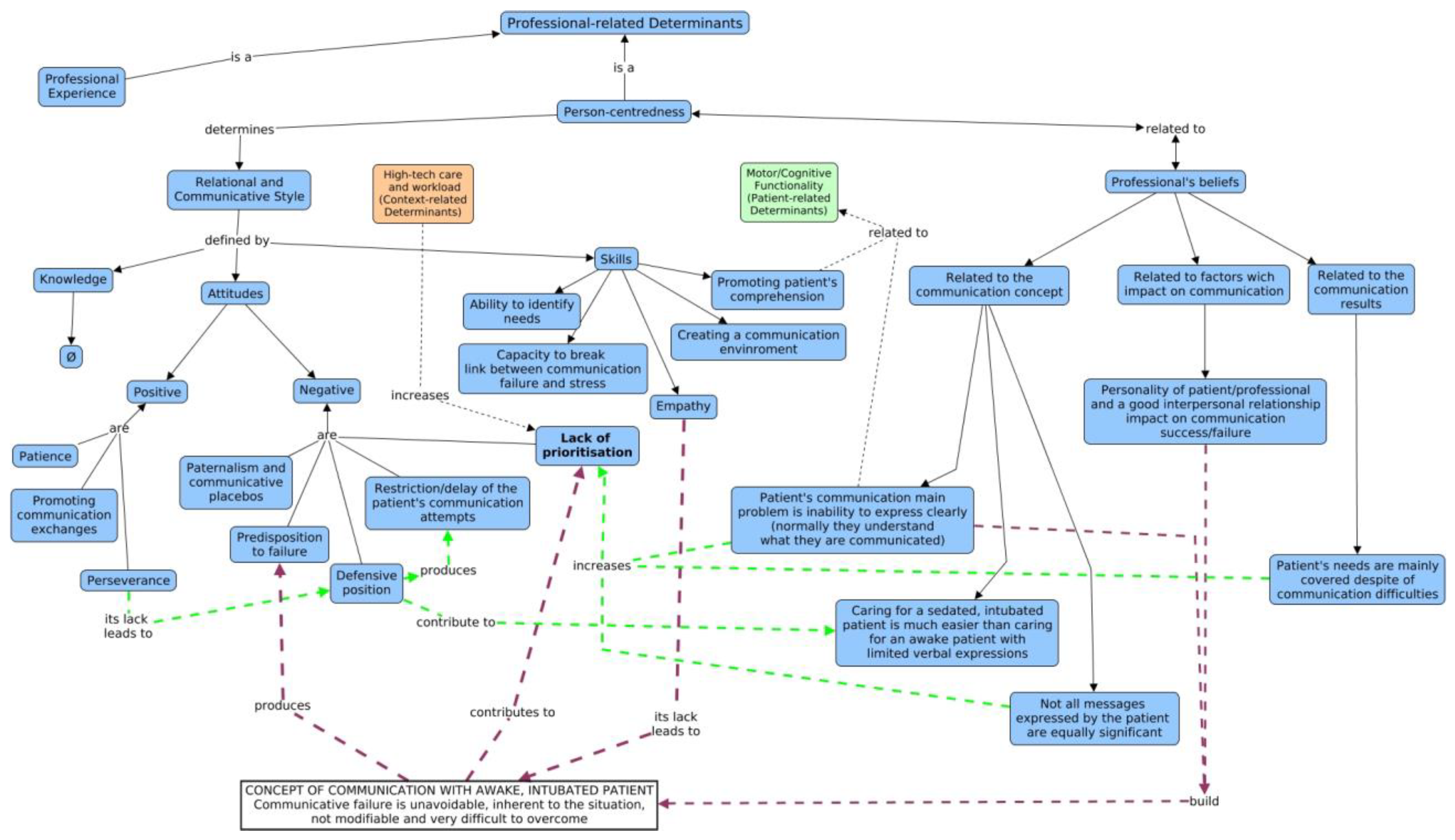

3.3. The Professional’s Determinants

3.3.1. Professional Experience

3.3.2. Person-Centredness

The Professional’s Relational and Communicative Style

- The professional’s skills

- The professional’s attitudes

- The professional’s knowledge

The Professional’s Beliefs

- Beliefs related to the communication concept

- Beliefs related to factors that impact on communication

- Beliefs related to the communication result

4. Discussion

- Patient-related determinants

- Context-related determinants

- Professionals’ determinants

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

7. Relevance to Clinical Practice

8. What Does This Research Contribute to the Wider Global Clinical Community?

- This study highlights the influence of the professionals’ determinants as a key element to approaching the communication problem with awake intubated patients.

- There is a close relationship between the professionals’ beliefs and their attitudes towards communication with those patients; it contributes to seeing it as a problem that is difficult to tackle, frustrating, and is a secondary priority.

- The identified multi-factor model allows the design of individualised strategies for improving the communication with these patients, overcoming the barriers identified and promoting communicative facilitators.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bergbom-Engberg, I.; Haljamäe, H. Assessment of Patients’ Experience of Discomforts during Respirator Therapy. Crit. Care Med. 1989, 17, 1068–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, R.M.; Flynn Makic, M.B.; Poteet, A.W.; Oman, K.S. The Ventilated Patient’s Experience. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2015, 34, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.M.; Sexton, D.L. Distress during Mechanivel Ventilation: Patients’ Perceptions. Crit. Care Nurse 1990, 10, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.; van Rooyen, D.; Strümpher, J. The Lived Experience of Patients on Mechanical Ventilation. Health SA Gesondheid 2002, 7, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggio, R.E.; Singer, R.D.; Hartman, K.; Sneider, R. Psychological Issues in the Care of Critically-Ill Respirator Patients: Differential Perceptions of Patients, Relatives, and Staff. Psychol. Rep. 1982, 51, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondi, A.J.; Chelluri, L.; Sirio, C.; Mendelsohn, A.; Schulz, R.; Belle, S.; Im, K.; Donahoe, M.; Pinsky, M.R. Patients’ Recollections of Stressful Experiences While Receiving Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation in an Intensive Care Unit. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 30, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, K.; Happ, M.B.; Costello, J.; Fried-Oken, M. AAC in the Intensive Care Unit. In Augmentative Communication Strategies for Adults with Acute or Chronic Medical Conditions; Beukelman, D.R., Yorkston, K.M., Garrett, K., Eds.; Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.: Baltimore, MD. USA, 2007; pp. 17–57. [Google Scholar]

- Happ, M.B.; Garrett, K.; DiVirgilio-Thomas, D.; Tate, J.; George, E.; Houze, M.; Radtke, J.; Sereika, S. Nurse-Patient Communication Interactions in the Intensive Care Unit. Am. J. Crit. Care 2011, 20, e28–e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leathart, A.J. Communication and Socialisation (1): An Exploratory Study and Explanation for Nurse-Patient Communication in an ITU. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 1994, 10, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salyer, J.; Stuart, B.J. Nurse-Patient Interaction in the Intensive Care Unit. Heart Lung 1985, 14, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Patak, L.; Gawlinski, A.; Fung, N.I.; Doering, L.; Berg, J. Patients’ Reports of Health Care Practitioner Interventions That Are Related to Communication during Mechanical Ventilation. Heart Lung 2004, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembo, A.C.; Higgins, I.; Parker, V. The Experience of Communication Difficulties in Critically Ill Patients in and beyond Intensive Care: Findings from a Larger Phenomenological Study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2015, 31, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, S.M. Silent, Slow Lifeworld: The Communication Experience of Nonvocal Ventilated Patients. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flinterud, S.I.; Andershed, B. Transitions in the Communication Experiences of Tracheostomised Patients in Intensive Care: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 2295–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, A. More than Nothing: The Lived Experience of Tracheostomy While Acutely Ill. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2010, 26, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, S.B. Impaired Verbal Communication during Short-Term Oral Intubation. Nurs. Diagn. 1997, 8, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P. Reclaiming the Everyday World: How Long-Term Ventilated Patients in Critical Care Seek to Gain Aspects of Power and Control over Their Environment. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2004, 20, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.; St John, W.; Moyle, W. Long-Term Mechanical Ventilation in a Critical Care Unit: Existing in an Uneveryday World. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 53, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasad, J.; Ahmad, M. Communication with Critically Ill Patients. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 50, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergbom-Engberg, I.; Haljamäe, H. The Communication Process with Ventilator Patients in the ICU as Perceived by the Nursing Staff. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 1993, 9, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, V.S.V.; Turkington, L. Communication Interaction in ICU--Patient and Staff Experiences and Perceptions. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2006, 22, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolotti, A.; Bagnasco, A.; Catania, G.; Aleo, G.; Pagnucci, N.; Cadorin, L.; Zanini, M.; Rocco, G.; Stievano, A.; Carnevale, F.A.; et al. The Communication Experience of Tracheostomy Patients with Nurses in the Intensive Care Unit: A Phenomenological Study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2018, 46, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallander Karlsen, M.M.; Heggdal, K.; Finset, A.; Heyn, L.G. Attention-Seeking Actions by Patients on Mechanical Ventilation in Intensive Care Units: A Phenomenological-Hermeneutical Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, G.; Blais, R.; Tamblyn, R.; Clermont, R.J.; MacGibbon, B. Impact of Patient Communication Problems on the Risk of Preventable Adverse Events in Acute Care Settings. Cmaj Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2008, 178, 1555–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, G.B.; Happ, M.B. Symptom Identification in the Chronically Critically Ill. AACN Adv. Crit. Care 2010, 21, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsig, A.; Steinacker, I. Communication with the Patient in the Intensive Care Unit… Intubated Patients. Nurs. Times 1982, 78, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Albarran, A.W. A Review of Communication with Intubated Patients and Those with Tracheostomies within an Intensive Care Environment. Intensive Care Nurs. 1991, 7, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaila, R.; Zbidat, W.; Anwar, K.; Bayya, A.; Linton, D.; Sviri, S. Communication Difficulties and Psychoemotional Distress in Patients Receiving Mechanical Ventilation. Am. J. Crit. Care 2011, 20, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, M.; Sereika, S.; Hoffman, L.; Barnato, A.; Donovan, H.; Happ, M. Nurse and Patient Interaction Behaviors’ Effects on Nursing Care Quality for Mechanically Ventilated Older Adults in the ICU. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2014, 7, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, M.; Sereika, S.; Happ, M. Nurse and Patient Characteristics Associated with Duration of Nurse Talk during Patient Encounters in ICU. Heart Lung 2013, 42, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, J.A.; Sereika, S.; Divirgilio, D.; Nilsen, M.; Demerci, J.; Campbell, G.; Happ, M.M.B. Symptom Communication During Critical Illness: The Impact of Age, Delirium, and Delirium Presentation. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2013, 39, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dithole, K.; Sibanda, S.; Moleki, M.M.; Thupayagale-Tshweneagae, G. Exploring Communication Challenges between Nurses and Mechanically Ventilated Patients in the Intensive Care Unit: A Structured Review. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2016, 13, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorne, S. Methodological Orthodoxy in Qualitative Nursing Research: Analysis of the Issues. Qual. Health Res. 1991, 1, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, A. Understanding Phenomenology. Nurse Res. 2010, 17, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowling, M. From Husserl to van Manen. A Review of Different Phenomenological Approaches. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I. Sampling in Qualitative Research. Purposeful and Theoretical Sampling; Merging or Clear Boundaries? J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 26, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Catálogo Nacional de Hospitales 2014. 2014. Available online: https://www.msssi.gob.es/ciudadanos/prestaciones/centrosServiciosSNS/hospitales/docs/CNH2014.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Perelló-Campaner, C. Rompiendo Silencios En La Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos. Fenomenología de La Comunicación Con Personas Intubadas, Perspectivas de Los Usuarios, Familiares y Profesionales de Enfermería, Universitat de les Illes Balears. 2019. Available online: https://www.educacion.gob.es/teseo/mostrarRef.do?ref=1834302 (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Bryman, A. Interviewing in Qualitative Research. In Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 312–333. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.; Bodgan, R. Introducción a Los Métodos Cualitativos de Investigación, 1st ed.; Paidós Ibérica: Barcelona, Spain, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Vandermause, R.; Fleming, S. Philosophical Hermeneutic Interviewing. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2011, 10, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, N. Qualitative Data, Analysis, and Design. In Introduction to Educational Research: A Critical Thinking Approach; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 342–386. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J. Data Were Saturated …. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 587–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan-Nicholls, K.; Will, C. Rigour in Qualitative Research: Mechanisms for Control. Nurse Res. 2009, 16, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broyles, L.M.; Tate, J.A.; Happ, M.B. Use of Augmentative and Alternative Communication Strategies by Family Members in the Intensive Care Unit. Am. J. Crit. Care 2012, 21, e21–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, E.H.; Light, J.; Kitko, L. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Nurse Communication with Patients with Complex Communication Needs with a Focus on the Use of Augmentative and Alternative Communication. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 2102–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, J.V.; Tate, J.A.; Happ, M.B. Nurses’ Perceptions of Communication Training in the ICU. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2012, 28, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handberg, C.; Voss, A.K. Implementing Augmentative and Alternative Communication in Critical Care Settings: Perspectives of Healthcare Professionals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happ, M.B.; Garrett, K.; Tate, J.; DiVirgilio, D.; Houze, M.; Demirci, J.; George, E.; Sereika, S. Effect of a Multi-Level Intervention on Nurse–Patient Communication in the Intensive Care Unit: Results of the SPEACS Trial. Heart Lung 2014, 43, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortensen, C.B.; Kjær, M.B.N.; Egerod, I. Caring for Non-Sedated Mechanically Ventilated Patients in ICU: A Qualitative Study Comparing Perspectives of Expert and Competent Nurses. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2019, 52, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttormson, J.L.; Khan, B.; Brodsky, M.B.; Chlan, L.L.; Curley, M.A.Q.; Gélinas, C.; Happ, M.B.; Herridge, M.; Hess, D.; Hetland, B.; et al. Symptom Assessment for Mechanically Ventilated Patients: Principles and Priorities: An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2023, 20, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, B.; McCance, T. Person-Centred Practice in Nursing and Health Care: Theory and Practice, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, B.; Karlsson, B.; Dewing, J.; Lerdal, A. Exploring Person-Centredness: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis of Four Studies. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2010, 24, 620–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Informant Code | Profession | Age | Gender | Professional Expertise (Total Years) | ICU Expertise (Total Years) | Years at Present ICU | Hospital | Coders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Nursing Assistant | 27 | Male | 9 | 8 | 7 | Hospital 1 | PC/MM |

| P2 | Nurse | 27 | Female | 6.5 | 5 | 5 | Hospital 1 | PC/AT |

| P3 | Nurse | 39 | Male | 16 | 14 | 9 | Hospital 1 | PC/GG |

| P4 | Nurse | 33 | Female | 10 | 6 | 6 | Hospital 2 | PC/GG |

| P5 | Nurse | 42 | Male | 10 | 10 | 10 | Hospital 2 | PC/GT |

| P6 | Nurse | 35 | Male | 7 | 5 | 2 | Hospital 3 | PC/MM |

| P7 | Nurse | 49 | Female | 27 | 26 | 26 | Hospital 3 | PC/MM |

| P8 | Nursing Assistant | 28 | Female | 9.5 | 7 | 7 | Hospital 2 | PC/GG |

| P9 | Nursing Assistant | 42 | Male | 12 | 7 | 7 | Hospital 3 | PC/AT |

| P10 | Nursing Assistant | 37 | Female | 12 | 11 | 11 | Hospital 3 | PC/AT |

| P11 | Nursing Assistant | 31 | Female | 13 | 10 | 6 | Hospital 1 | PC/GT |

| Patient’s Physical and Cognitive Functionality |

| Tracheostomy vs. orotracheal tube |

| “because [with tracheostomy] the lip mobility is complete and […] articulation is much better” (P6). |

| Lack of sensory aids/dentures |

| “many times […] they are elderly people, they don’t have teeth, you know? […] their cheeks are […] inwards and you don’t understand them [when mouthing]” (P4a). |

| Lack of physical strength |

| “Patients who don’t have strength, who are bedridden, they can’t use their hands to write or to point on the communication chart nor make any gestures” (P2). |

| Other factors limiting motor function |

| “[…], of course, an oedematous patient, badly seated, unable to write well, who […] then asks for pen and paper and writes […] trying to use good handwriting, but he can’t do it well, this makes communication still more difficult” (P3). |

| Alteration of cognition |

| “when they are intubated, you don’t know whether they understand much of what you explain them; you’re trying to tell them something and they say “yes”, but after a while they’re back with the same matter and you realise that they haven’t understood it; so you don’t know whether they’re confused or not” (P8). |

| Discomfort |

| “State of mind, an anxious or restless state, pain […] has much to do, sometimes [the patient’s] anxiety makes communication [with him] impossible” (P5). |

| Patient’s relational and communicative style |

| “I think that the […] inpatient’s personality […] has a great influence. There are very anxious people, so then, when you try to advise them that they can try to communicate with you in some form, there is no [no way] […]. You clearly notice when a person is calm or has got a smooth character, then there arrives a moment when his eyes tell you “well, you don’t understand me, don’t bother, it doesn’t matter” (P4b). |

| Personal circumstances |

| “for example, most [COPD patients] who had been admitted many many times […] know the process very well, some even talk with the tube in place, which means that you understand them quite well” (P10). |

| Family Presence |

| “sometimes I couldn’t understand, didn’t know what the patient says, and then his family immediately say “see, it’s about this or that” […]. Of course, they know him well” (P8a). “Many times it’s the family who brings in a whiteboard” (P2a). “Yes, […] when the patient tries to speak, the ventilator beeps and […] [relatives] become more anxious, so often they tell the patient “don’t speak, don’t speak, don’t say anything” (P2b). |

| ICU inherent characteristics |

| “at sometimes there forms such a noise that it makes [communication] difficult […] as there is no peace to be able to listen to [or understand] him” (P3). “Also, ICU is a place where they use so much technology, they use many techniques and most professionals don’t see the patient […] as a person, they see [him] as a disease that requires certain technologies and they administer them, that’s all” (P10). |

| Time organisation, workload and continuity of care |

| “sometimes, when the workload is high, you have so much to do, you’re there trying to understand what he wants to ask, […] you don’t understand, you’ve got things to do […] and you don’t have time” (P4a). “the longer they have stayed in, the easier it becomes to understand them, that’s true” (P4b). |

| Availability and features of the communication aids |

| “[regarding the communication board] I don’t even know whether there is one in every unit and it must be you who looks for it in every drawer until you finally find it. There is no clearly assigned place, not everybody uses it, far from using it every day […] when you ask for it, you don’t find it” (P6). “In this alphabet there are a few pictures, but far too little. Maybe there is some fruit or a pen... that’s very little. […] Patients hardly ever go to the pictures, maybe because it is a small alphabet with small pictures; I’m quite sure that more than half [the patients] don’t see properly. […] Perhaps if we had bigger charts [...] it would be easier than with those small ones” (P8b). “they want to write the whole sentence on the board and as it works letter by letter they become more desperate” (P5a). |

| Features of the message |

| “It’s because you go with preconceived ideas […] and ask him whether he feels comfortable, if he’s in pain, hungry, if […] he’s cold, these are the questions you’re going to ask the patient; […] [if] the patient answers that he wants to see his son, […] how can he make you understand that he wishes to see his wife or his family, when you don’t have the same preconception?” (P5b). “please write it in capital letter so we can see it” (P9). |

| Person-Centredness (Pseudo-Holistic Approach) |

| “[during hygiene] I like to ask them whether it bothers them when we [the professionals] talk about our matters, because […] it seems as if you didn’t pay them any attention, you see? And I think that it’s important to ask them, but we don’t always do it, you see? But, mainly when they are more awake, “do you mind if we talk about this or that?” […] “does it bother you if we talk about that?” “No”, because he, well, he watches and is aware of it too” (P7a). |

| Professional’s skills |

| “[The patients] try to communicate and you begin […] “What’s the matter? Pain?” […] “What troubles you? The tube?” […] we have more experience in lip reading and we feel what problem or trouble they may have […] I make sure to have all those factors under control so it’s not them that cause the need of communication, and then I have to draw on him writing or me trying to read his lips or ask questions” (P6a). “When you see that he becomes nervous, you stop; […] my method is to wait for a while and then I start again… [...] you wait a while until he calms down; [...] I think that [it’s appropriate] to stop a little and then start again” (P7b). |

| Professional’s attitudes |

| “other [professionals] […] who spend more time, have more patience, stay longer by the bed until they achieve to understand them” (P2). “You always start with “good morning, good afternoon, how did you spend the afternoon, do you remember me?”, you see? In a way, starting to talk almost as if he didn’t have the tube, you know? And you don’t wait for his answer, but you keep on talking. […] When the family is there, the family doesn’t understand him and then they become nervous because maybe he asks something of the family, something personal, from outside the hospital, you see? Then you must help them a bit and mediate also between family and patient. It’s a little like this […]” (P7c). “In general, standing beside the patient in order to talk with him is not really a habit we have [the professionals]” (P3). “Well I don’t know in which way [it could be improved], the truth is that I never have thought about it” (P8). “don’t worry, within two days they will remove you the tube, don’t worry” (P7d). Many times… they want to write, and writing doesn’t always yield positive results […] but, well, to calm them down, you let them write, but most of the times […] you don’t understand what they write, you know? Or many times you see some scribbling, […] but, why, sometimes they calm down because […] they wrote their discourse, you know? […] don’t ever tell them that they [cannot write], because they need to try, and then you have to tell them that yes, they did it, they wrote, and then they calm down: “yes, I understand”, “ah, OK”, you only need to say “ah, OK”, even if they haven’t written anything, you see? and they calm down a little” (P7e). |

| Professional’s beliefs. |

| “to me it’s much more difficult to understand them than to explain myself, because I can tell them everything I’m doing to them, why I’m doing… ” (P4a). “it’s more complicated because… they should be sedated and they aren’t, and of course they ask many questions you don’t understand and you don’t know how to answer” (P1). “many times [patients] are confused and you think that they want to tell you something important, but it’s a result of their disorientation” (P6b). “I think that the patient’s personality and that of the professionals’ involved with the patient have an impact, as communication is not the same with one professional or another” (P10). “Let’s see, sometimes the professional’s character also clashes with the patient’s character, […] there are very patient nurses and others with less patience” (P4b). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perelló-Campaner, C.; González-Trujillo, A.; Alorda-Terrassa, C.; González-Gascúe, M.; Pérez-Castelló, J.A.; Morales-Asencio, J.M.; Molina-Mula, J. Determinants of Communication Failure in Intubated Critically Ill Patients: A Qualitative Phenomenological Study from the Perspective of Critical Care Nurses. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2645. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11192645

Perelló-Campaner C, González-Trujillo A, Alorda-Terrassa C, González-Gascúe M, Pérez-Castelló JA, Morales-Asencio JM, Molina-Mula J. Determinants of Communication Failure in Intubated Critically Ill Patients: A Qualitative Phenomenological Study from the Perspective of Critical Care Nurses. Healthcare. 2023; 11(19):2645. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11192645

Chicago/Turabian StylePerelló-Campaner, Catalina, Antonio González-Trujillo, Carme Alorda-Terrassa, Maite González-Gascúe, Josep Antoni Pérez-Castelló, José Miguel Morales-Asencio, and Jesús Molina-Mula. 2023. "Determinants of Communication Failure in Intubated Critically Ill Patients: A Qualitative Phenomenological Study from the Perspective of Critical Care Nurses" Healthcare 11, no. 19: 2645. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11192645

APA StylePerelló-Campaner, C., González-Trujillo, A., Alorda-Terrassa, C., González-Gascúe, M., Pérez-Castelló, J. A., Morales-Asencio, J. M., & Molina-Mula, J. (2023). Determinants of Communication Failure in Intubated Critically Ill Patients: A Qualitative Phenomenological Study from the Perspective of Critical Care Nurses. Healthcare, 11(19), 2645. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11192645