Relationship of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Stage and Hepatic Function to Health-Related Quality of Life: A Single Center Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data, Staging/Classification, and Fact-Hep Scores for the Overall Cohort

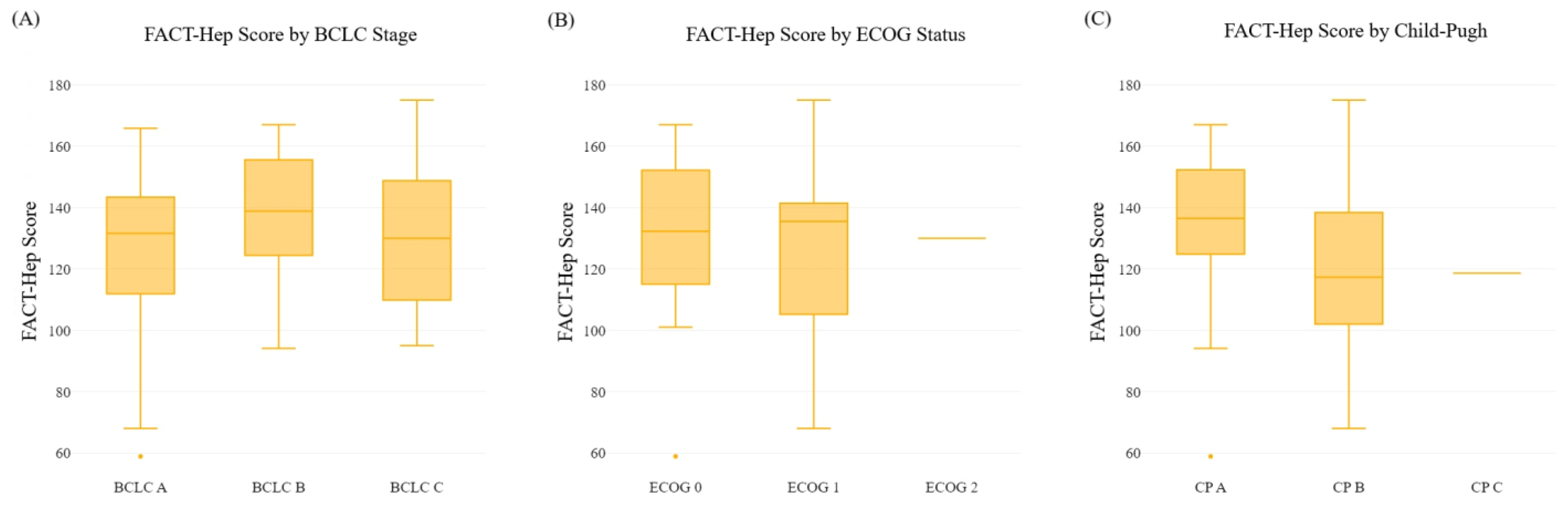

3.2. Association between FACT-Hep Scores and BCLC, ECOG, and Child–Pugh at Diagnosis

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Explanation and Comparison with Similar Research

4.3. Implications and Actions Needed

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahib, L.; Smith, B.D.; Aizenberg, R.; Rosenzweig, A.B.; Fleshman, J.M.; Matrisian, L.M. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: The unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 2913–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llovet, J.M.; Montal, R.; Sia, D.; Finn, R.S. Molecular therapies and precision medicine for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llovet, J.M.; Kelley, R.K.; Villanueva, A.; Singal, A.; Pikarsky, E.; Roayaie, S. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Lim, H.Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.V.; Merle, P.; et al. IMbrave150: Updated overall survival (OS) data from a global, randomized, open-label phase III study of atezolizumab (atezo) + bevacizumab (bev) versus sorafenib (sor) in patients (pts) with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; Kaseb, A.O.; et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, C.O.; Ricco, G.; Ozdogan, O.C.; Baltacioglu, F.; Ones, T.; Yumuk, P.F.; Dulundu, E.; Uzun, S.; Colombatto, P.; Oliveri, F.; et al. Proposal and Validation of a Novel Scoring System for Hepatocellular Carcinomas Beyond Curability Borders. Hepatol. Commun. 2021, 6, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PonS, F.; Varela, M.; Llovet, J. Staging systems in hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB 2005, 7, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoris, A.; Marlar, C.A. Use of the child pugh score in liver disease. [Updated 2022]. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542308/ (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Nishikawa, H.; Kita, R.; Kimura, T.; Ohara, Y.; Sakamoto, A.; Saito, S.; Nishijima, N.; Nasu, A.; Komekado, H.; Osaki, Y. Clinical Implication of Performance Status in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Complicating with Cirrhosis. J. Cancer 2015, 6, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slevin, M.L. Quality of life: Philosophical question or clinical reality? BMJ 1992, 305, 466–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, S.; Khubchandani, S.; Iyer, R. Quality of life and hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2014, 5, 296–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Shim, S.; Cho, J.; Lim, H.K. Systematic Review of Studies Assessing the Health-Related Quality of Life of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients from 2009 to 2018. Korean J. Radiol. 2020, 21, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balogh, J.; David Victor, I.; Asham, E.H.; Burroughs, S.G.; Boktour, M.; Saharia, A.; Li, X.; Ghobrial, R.M.; Monsour, H.P., Jr. Hepatocellular carcinoma: A review. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2016, 3, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steel, J.; Hess, S.A.; Tunke, L.; Chopra, K.; Carr, B.I. Sexual functioning in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2005, 104, 2234–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikoshiba, N.; Miyashita, M.; Sakai, T.; Tateishi, R.; Koike, K. Depressive symptoms after treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma survivors: Prevalence, determinants, and impact on health-related quality of life. Psycho-Oncology 2013, 22, 2347–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montazeri, A. Quality of life data as prognostic indicators of survival in cancer patients: An overview of the literature from 1982 to 2008. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2009, 7, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinten, C.; Msc, F.M.; Coens, C.; Sprangers, M.A.G.; Ringash, J.; Gotay, C.; Bjordal, K.; Greimel, E.; Reeve, B.B.; Maringwa, J.; et al. A global analysis of multitrial data investigating quality of life and symptoms as prognostic factors for survival in different tumor sites. Cancer 2013, 120, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmür, A.; Kolly, P.; Knöpfli, M.; Dufour, J. FACT-Hep increases the accuracy of survival prediction in HCC patients when added to ECOG Performance Status. Liver Int. 2018, 38, 1468–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, N.; Cella, D.; Webster, K.; Odom, L.; Martone, M.; Passik, S.; Bookbinder, M.; Fong, Y.; Jarnagin, W.; Blumgart, L. Measuring Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Hepatobiliary Cancers: The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Hepatobiliary Questionnaire. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 2229–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.F.; Tulsky, D.S.; Gray, G.; Sarafian, B.; Linn, E.; Bonomi, A.; Silberman, M.; Yellen, S.B.; Winicour, P.; Brannon, J. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J. Clin. Oncol. 1993, 11, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, K.; Cella, D.; Yost, K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System: Properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, J.; Davies, S.; Roydhouse, J.K.; Fethney, J.; White, K. The effect of cancer stage and treatment modality on quality of life in oropharyngeal cancer. Laryngoscope 2013, 124, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zeng, H.; Xia, R.; Chen, G.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Guo, G.; Song, G.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Health-related quality of life of esophageal cancer patients in daily life after treatment: A multicenter cross-sectional study in China. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 5803–5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Du, L.; Huang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhu, J.; Li, H.; Bai, Y.; Liao, X.; Mao, A.; et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with esophageal cancer or precancerous lesions assessed by EQ-5D: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Thorac. Cancer 2020, 11, 1076–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, H.; Williams, R.; Dempsey, H.; Stanway, S.; Smeeth, L.; Bhaskaran, K. Quality of life and mental health in breast cancer survivors compared with non-cancer controls: A study of patient-reported outcomes in the United Kingdom. J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 15, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K.; Folwarski, M.; Ruszkowski, J.; Świerblewski, M.; Makarewicz, W. Influence of malnutrition stage according to GLIM 2019 criteria and SGA on the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. Nutr. Hosp. 2020, 37, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mol, M.; Visser, S.; Aerts, J.; Lodder, P.; van Walree, N.; Belderbos, H.; Oudsten, B.D. The association of depressive symptoms, personality traits, and sociodemographic factors with health-related quality of life and quality of life in patients with advanced-stage lung cancer: An observational multi-center cohort study. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.K.H.; Lam, C.L.K.; Poon, J.T.C.; Kwong, D.L.W. Clinical Correlates of Health Preference and Generic Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Colorectal Neoplasms. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, A.; Onoda, H.; Fushiya, N.; Koike, K.; Nishino, H.; Tajiri, H. Staging systems for hepatocellular carcinoma: Current status and future perspectives. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, V.C.-Y.; Sarna, L. Symptom Management in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2008, 12, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okediji, P.T.; Salako, O.; Fatiregun, O.O. Pattern and Predictors of Unmet Supportive Care Needs in Cancer Patients. Cureus 2017, 9, e1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Zhang, W.; You, S.; Li, M.; Lei, L.; Chen, L. A nomogram for predicting depression in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: An observational cross-sectional study. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2019, 23, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niezgoda, H.E.; Pater, J.L. A validation study of the domains of the core EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire. Qual. Life Res. 1993, 2, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwer, L.; Rotonda, C.; Guillemin, F.; Miny, J.; Kaminsky, M.-C.; Mercier, M.; Tournier-Rangeard, L.; Leonard, I.; Montcuquet, P.; Rauch, P.; et al. Responsiveness of EORTC QLQ-C30, QLQ-CR38 and FACT-C quality of life questionnaires in patients with colorectal cancer. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2011, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piovani, D.; Nikolopoulos, G.K.; Bonovas, S. Pitfalls and perils of survival analysis under incorrect assumptions: The case of COVID-19 data. Biomedica 2021, 41, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age, y | Median (IQR) | 69 (62.5 to 75) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 37 (72.5) | |

| Female | 14 (27.5) | |

| Diagnostic method, n (%) | ||

| Pathological | 24 (47.1) | |

| Radiological | 27 (52.9) | |

| Liver disease etiology, n (%) | ||

| No liver disease | 6 (11.8) | |

| Hepatitis C | 15 (29.4) | |

| Hepatitis B | 1 (2.0) | |

| NASH/NAFLD | 15 (29.4) | |

| ETOH | 5 (9.8) | |

| Other | 4 (7.8) | |

| Unknown | 5 (9.8) | |

| BCLC stage, n (%) | ||

| A | 21 (41.2) | |

| B | 13 (25.5) | |

| C | 17 (33.3) | |

| D | 0 (0.0) | |

| ECOG Performance Status, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 28 (54.9) | |

| 1 | 22 (43.1) | |

| 2 | 1 (2.0) | |

| Child–Pugh, n (%) | ||

| A | 38 (74.5) | |

| B | 12 (23.5) | |

| C | 1 (2.0) | |

| Prior treatment, n (%) * | (n = 50) | |

| Locoregional | 11 (22.0) | |

| Surgery | 4 (8.0) | |

| Systemic | 3 (6.0) | |

| Transplant | 1 (2.0) | |

| None | 40 (80.0) | |

| PWB | Mean ± SD | 21.3 ± 5.9 |

| SWB | Mean ± SD | 22.1 ± 5.1 |

| EWB | Mean ± SD | 16.2 ± 4.6 |

| FWB | Mean ± SD | 16.4 ± 6.6 |

| HCS | Mean ± SD | 54.3 ± 11.7 |

| FACT-Hep score | Mean ± SD | 130.3 ± 20.3 |

| FACT-Hep Trial Outcome Index | Mean ± SD | 92.4 ± 20.3 |

| FACT-G Score | Mean ± SD | 75.9 ± 16.7 |

| Variables, Mean ± SD | PWB | SWB | EWB | FWB | HCS | FACT-G Score | FACT-Hep Trial | FACT-Hep Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCLC stage | |||||||||

| A | 21.7 ± 5.9 | 21.1 ± 5.4 | 14.5 ± 4.9 | 15.8 ± 6.1 | 52.8 ± 13.1 | 73.2 ± 18.1 | 91.4 ± 20.8 | 126.0 ± 28.1 | |

| B | 21.9 ± 6.3 | 23.7 ± 5.9 | 16.1 ± 4.5 | 16.7 ± 7.4 | 58.5 ± 8.4 | 78.4 ± 17.4 | 97.1 ± 18.7 | 136.9 ± 22.8 | |

| C | 20.4 ± 5.5 | 22.3 ± 3.7 | 18.2 ± 3.4 | 16.8 ± 6.5 | 52.8 ± 11.4 | 77.7 ± 13.8 | 90.0 ± 20.5 | 130.5 ± 22.7 | |

| p-value a | 0.518 | 0.124 | 0.001 | 0.799 | 0.098 | 0.350 | 0.371 | 0.224 | |

| ECOG Performance Status | |||||||||

| 0 | 22.2 ± 5.3 | 21.5 ± 5.5 | 15.4 ± 4.5 | 18.1 ± 6.2 | 55.5 ± 10.4 | 77.2 ± 16.4 | 95.8 ± 19.3 | 132.6 ± 24.3 | |

| 1 | 20.1 ± 6.5 | 23.0 ± 4.7 | 17.2 ± 4.6 | 14.5 ± 6.5 | 52.5 ± 13.2 | 74.8 ± 17.2 | 88.0 ± 21.2 | 127.3 ± 27.0 | |

| 2 | 23.0 | 21.0 | 17.0 | 9.0 | 60.0 | 70.0 | 92.0 | 130.0 | |

| p-value a | 0.174 | 0.364 | 0.140 | 0.006 | 0.354 | 0.680 | 0.166 | 0.577 | |

| Child–Pugh | |||||||||

| A | 22.2 ± 5.8 | 22.2 ± 4.7 | 15.8 ± 4.5 | 17.4 ± 6.6 | 56.7 ± 9.6 | 77.6 ± 16.7 | 96.3 ± 19.2 | 134.3 ± 23.8 | |

| B | 19.3 ± 5.3 | 21.7 ± 6.5 | 17.3 ± 4.8 | 13.5 ± 5.8 | 46.7 ± 14.6 | 71.8 ± 16.3 | 81.2 ± 19.8 | 118.5 ± 27.3 | |

| C | 14.0 | 25.6 | 15.0 | 13.0 | 51.0 | 67.6 | 78.0 | 118.6 | |

| p-value a | 0.018 | 0.576 | 0.346 | 0.030 | <0.001 | 0.255 | 0.003 | 0.021 | |

| Gender | Female | 21.3 ± 5.7 | 22.3 ± 4.7 | 15.9 ± 5 | 15.7 ± 6.7 | 55.5 ± 12.9 | 75.2 ± 15.5 | 91.4 ± 22.3 | 129.6 ± 26.2 |

| Male | 21.4 ± 6.0 | 22.1 ± 5.4 | 16.3 ± 4.5 | 16.6 ± 6.6 | 54.2 ± 11.4 | 76.3 ± 17.3 | 92.7 ± 19.8 | 130.5 ± 25.4 | |

| p-value b | 0.961 | 0.916 | 0.838 | 0.677 | 0.944 | 0.824 | 0.856 | 0.918 | |

| Age | <65 | 20.3 ± 7.0 | 20.7 ± 6.3 | 16.6 ± 5.6 | 15.9 ± 7.3 | 55.1 ± 11.1 | 73.5 ± 21.3 | 91.3 ± 23.8 | 128.6 ± 30.8 |

| >65 | 21.7 ± 5.4 | 22.7 ± 4.6 | 16.0 ± 4.2 | 16.5 ± 6.4 | 53.9 ± 12.1 | 76.9 ± 14.8 | 92.7 ± 19.2 | 130.9 ± 23.5 | |

| p-value b | 0.488 | 0.300 | 0.713 | 0.799 | 0.748 | 0.591 | 0.842 | 0.809 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gupta, A.; Zorzi, J.; Ho, W.J.; Baretti, M.; Azad, N.S.; Griffith, P.; Dao, D.; Kim, A.; Philosophe, B.; Georgiades, C.; et al. Relationship of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Stage and Hepatic Function to Health-Related Quality of Life: A Single Center Analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182571

Gupta A, Zorzi J, Ho WJ, Baretti M, Azad NS, Griffith P, Dao D, Kim A, Philosophe B, Georgiades C, et al. Relationship of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Stage and Hepatic Function to Health-Related Quality of Life: A Single Center Analysis. Healthcare. 2023; 11(18):2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182571

Chicago/Turabian StyleGupta, Amol, Jane Zorzi, Won Jin Ho, Marina Baretti, Nilofer Saba Azad, Paige Griffith, Doan Dao, Amy Kim, Benjamin Philosophe, Christos Georgiades, and et al. 2023. "Relationship of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Stage and Hepatic Function to Health-Related Quality of Life: A Single Center Analysis" Healthcare 11, no. 18: 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182571

APA StyleGupta, A., Zorzi, J., Ho, W. J., Baretti, M., Azad, N. S., Griffith, P., Dao, D., Kim, A., Philosophe, B., Georgiades, C., Kamel, I., Burkhart, R., Liddell, R., Hong, K., Shubert, C., Lafaro, K., Meyer, J., Anders, R., Burns, W., III, & Yarchoan, M. (2023). Relationship of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Stage and Hepatic Function to Health-Related Quality of Life: A Single Center Analysis. Healthcare, 11(18), 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182571