Service Climate and Nurses’ Collaboration with Families of Older Patients in the Care Process during Hospitalization

Abstract

1. Introduction

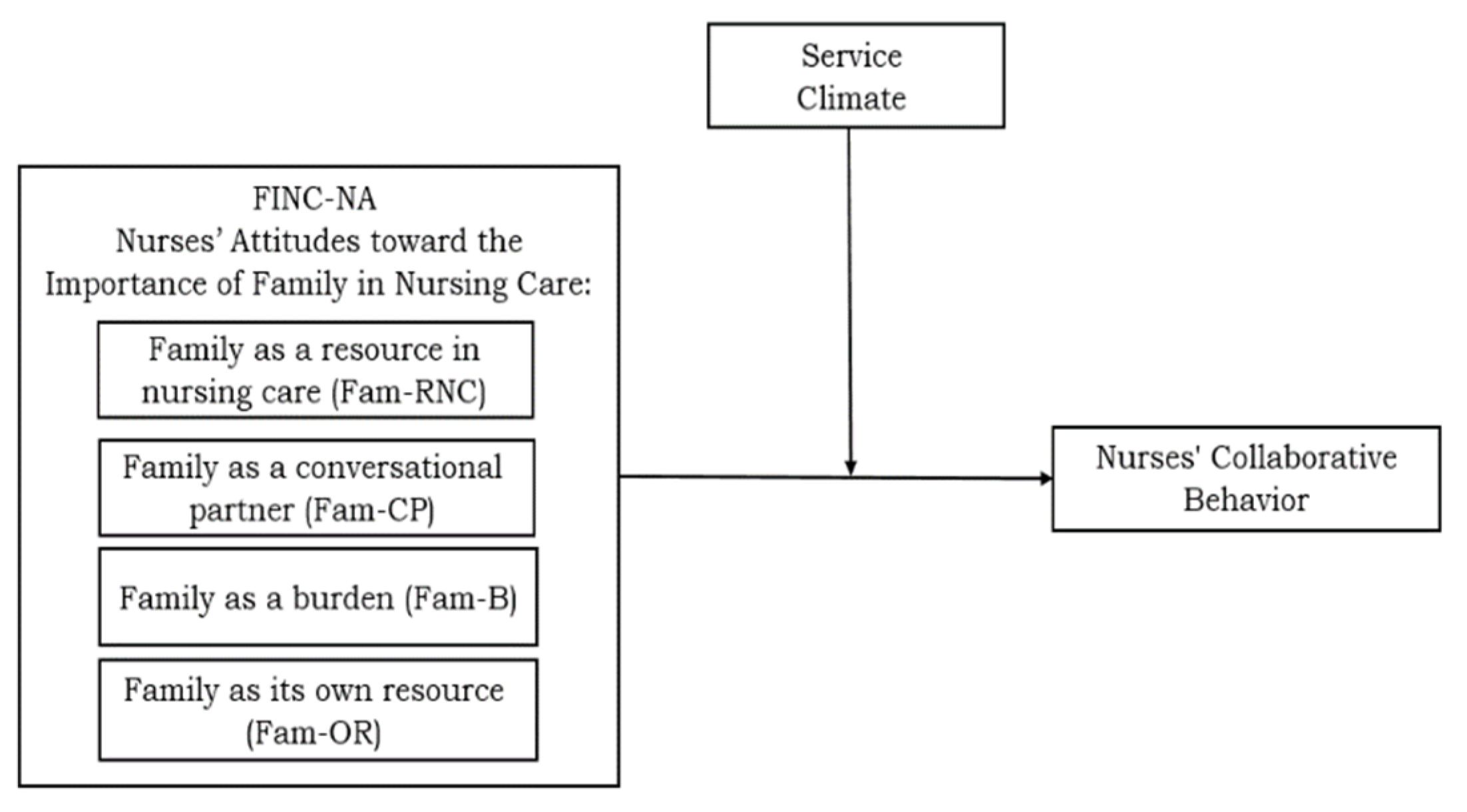

1.1. The Influence of Service Climate on the Relationship between Nurses’ Attitudes toward the Family in Nursing Care and on Nurses Collaborative Behavior

1.2. Research Aims and Hypotheses

- (a)

- Illuminate the role of a ward’s service climate in cultivating nurses’ collaboration with family members.

- (b)

- Examine the moderating effects of service climate on the relationship between nurses’ attitudes toward the importance of the family in nursing care and their collaborative behavior in their interaction with the family in the care process.

- (c)

- Underscore how nurses’ perceptions and attitudes are important to the collaboration of family members in the care processes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

2.3. Variables and Measurements

Demographic Characteristics

2.4. Measures

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

3.2. Correlations between Study Measures

3.3. Multiple Regression Analysis Predicting Nurses’ Collaborative Behavior

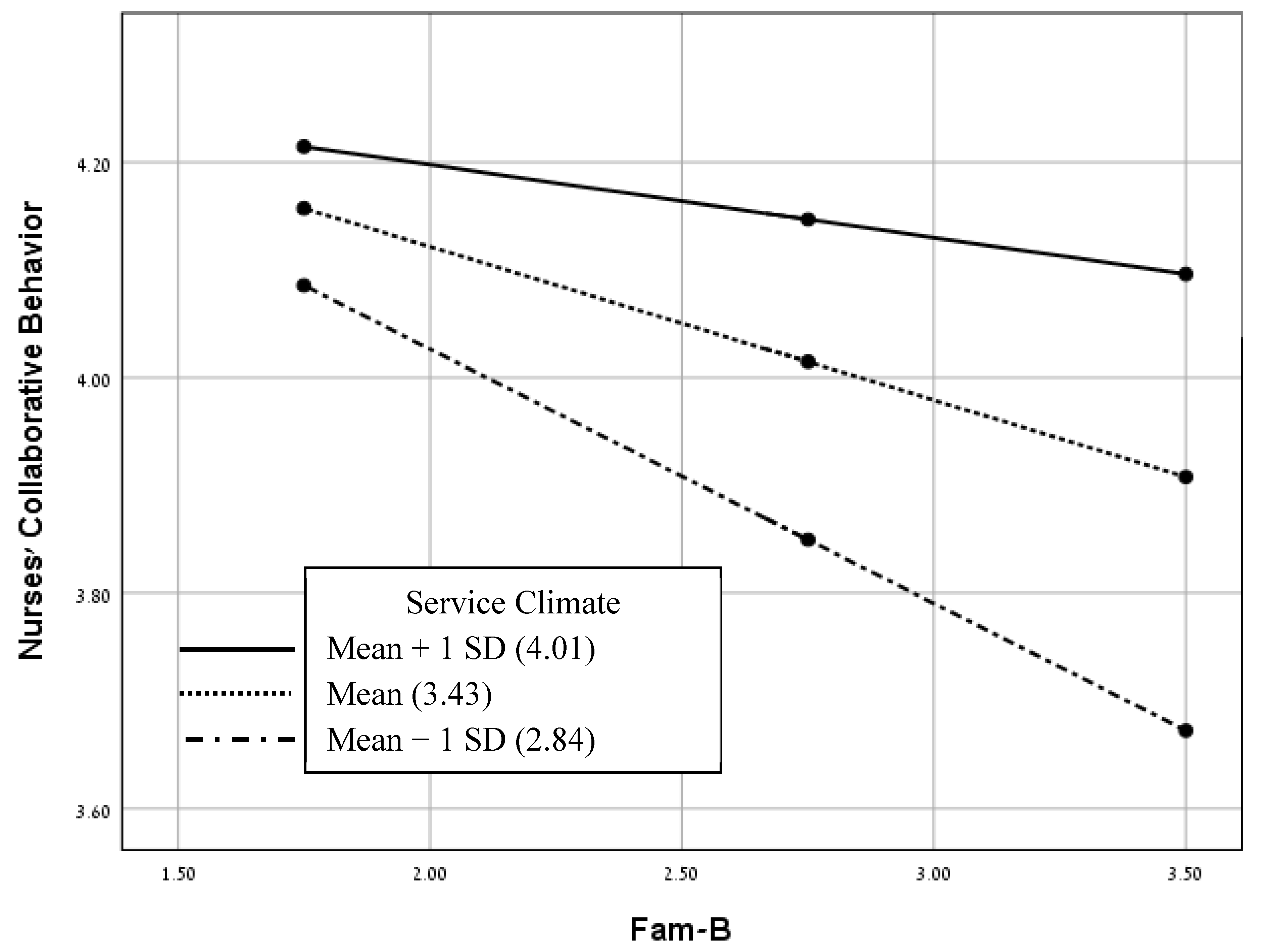

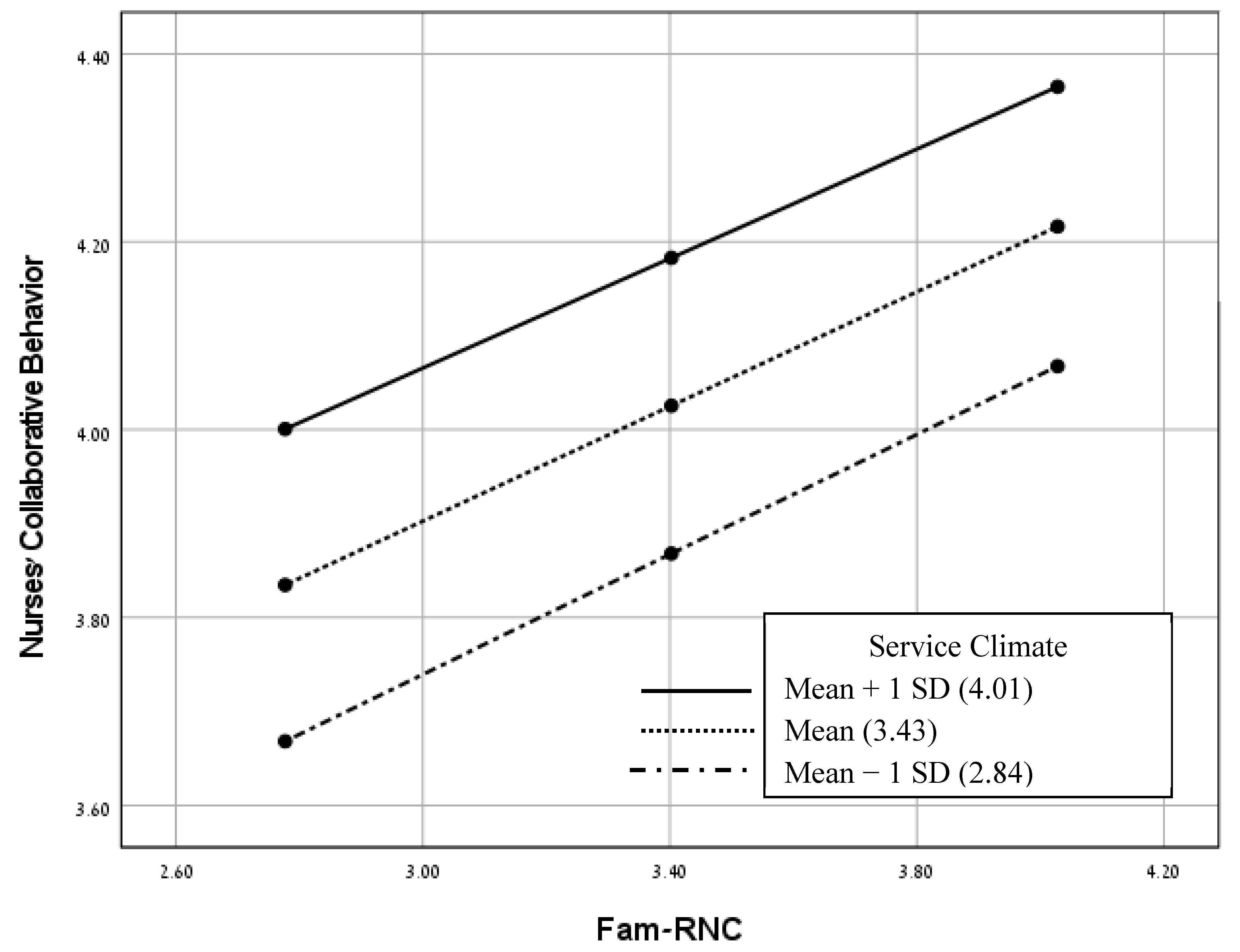

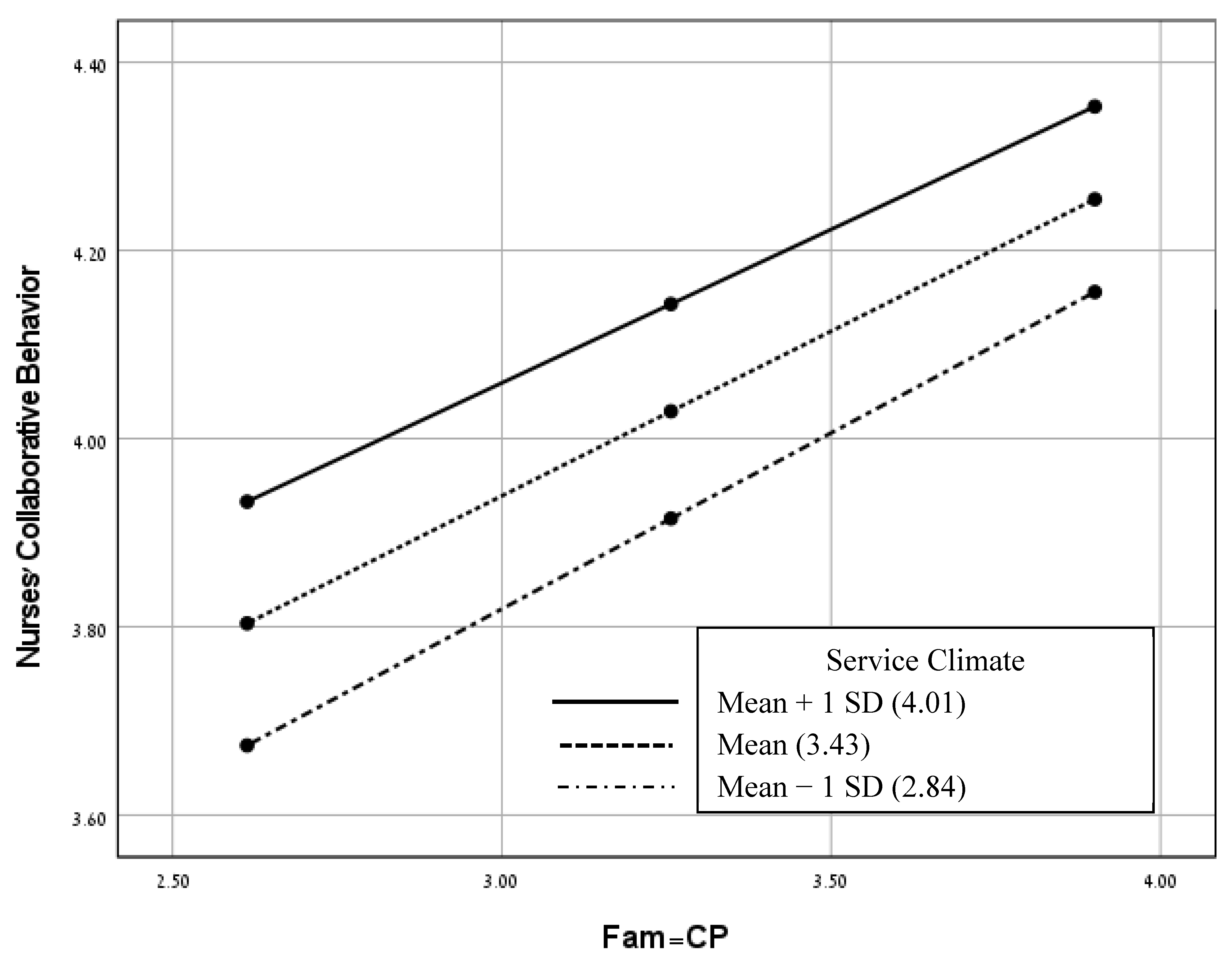

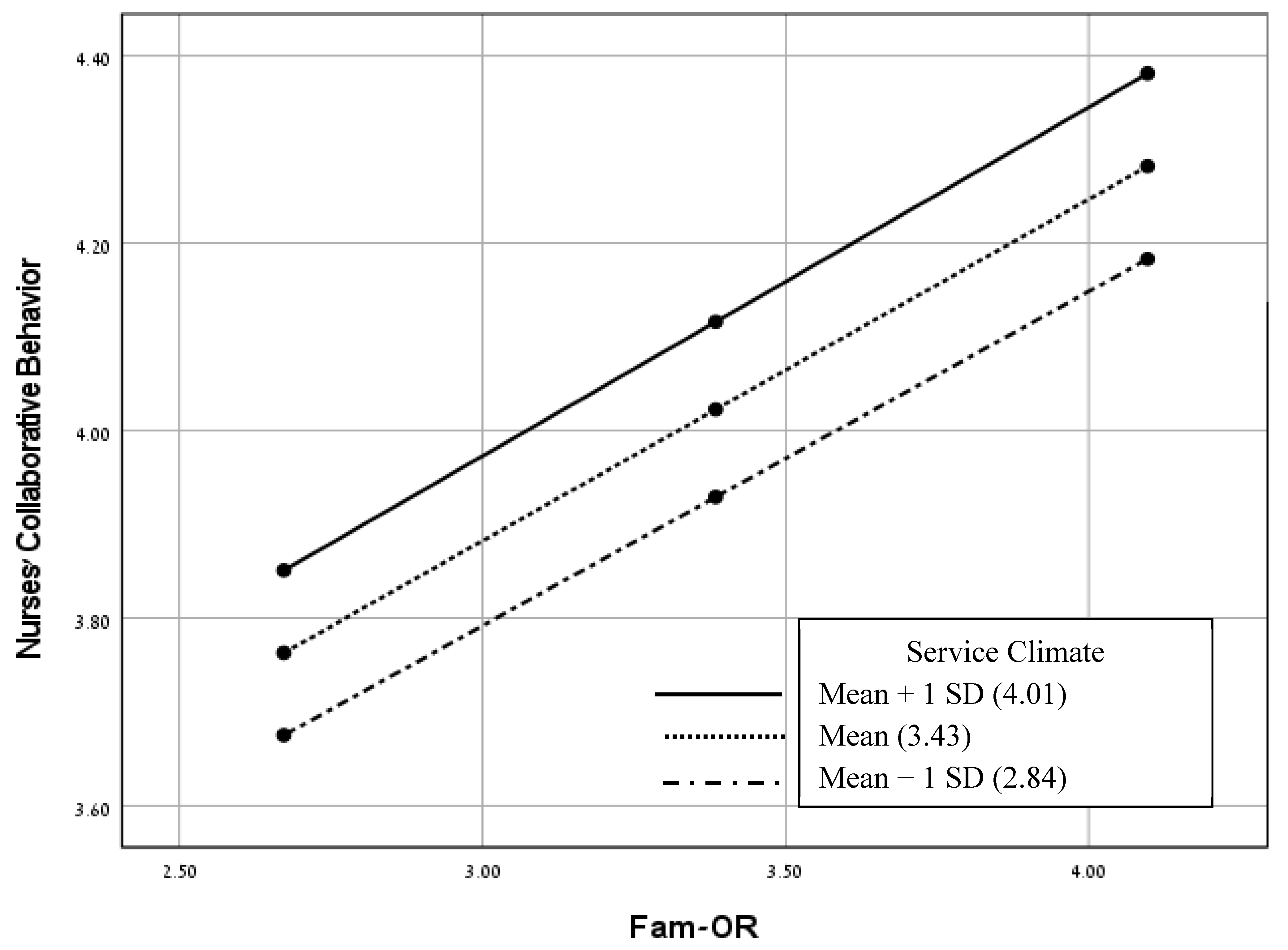

3.4. Service Climate as Moderating between FINC-NA and Nurses’ Collaborative Behavior

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications for Nursing and Health Policies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goldschmidt, K.; Mele, C. Disruption of patient and family centered care through the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 58, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaslow, N.J.; Dunn, S.E.; Bonsall, J.M.; Mekonnen, E.; Newsome, J.; Pendley, A.M.; Wierson, M.; Schwartz, A.C. A roadmap for patient-and family-centered care during the pandemic. Couple Fam. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2021, 10, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.L.; Turnbull, A.E.; Oppenheim, I.M.; Courtright, K.R. Family-centered care during the COVID-19 era. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, e93–e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bienassis, K.; Mieloch, Z.; Slawomirski, L.; Klazinga, N. Advancing Patient Safety Governance in the COVID-19 Response. OECD Health Working Papers No. 150. 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/advancing-patient-safety-governance-in-the-covid-19-response_9b4a9484-en (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Bragstad, L.K.; Kirkevold, M.; Hofoss, D.; Foss, C. Informal caregivers’ participation when older adults in Norway are discharged from the hospital. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2014, 22, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, E.I.; Paans, W.; Jaarsma, T.; Keers, J.C.; van der Schans, C.P.; Luttik, M.L.A. The importance of families in nursing care: Attitudes of nurses in the Netherlands. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 35, 1207–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, L.F. Moving toward person-and family-centered care. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2014, 24, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J.L.; Boyd, C.M. A look at person-centered and family-centered care among older adults: Results from a national survey. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 1497–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranley, L.A.; Lam, S.C.; Brennenstuhl, S.; Kabir, Z.N.; Boström, A.M.; Leung, A.Y.M.; Konradsen, H. Nurses’ attitudes toward the importance of families in nursing care: A multinational comparative study. J. Fam. Nurs. 2022, 28, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, L.; Bourbonnais, A.; Bernier, R.; Benoit, M. Communication between nurses and family caregivers of hospitalised older persons: A literature review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaslow, N.J.; Dunn, S.E.; Henry, T.; Partin, C.; Newsome, J.; O’Donnell, C.; Wierson, M.; Schwartz, A.C. Collaborative patient-and family-centered care for hospitalized individuals: Best practices for hospitalist care teams. Fam. Syst. Health 2020, 38, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiwanuka, F.; Shayan, S.J.; Tolulope, A.A. Barriers to patient and family-centred care in adult intensive care units: A systematic review. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhadi, N.; Drach-Zahavy, A. Promoting patient care: Work engagement as a mediator between ward service climate and patient-centred care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Sambasivan, M.; Kumar, N. Effect of spiritual intelligence, emotional intelligence, psychological ownership and burnout on caring behaviour of nurses: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 3192–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Director Circular. Improving Patient Experience in Healthcare System; Circular No. 06/13; Ministry of Health: Jerusalem, Israel, 2013. (In Hebrew)

- Ben Natan, M.; Hochman, O. Patient-centered care in healthcare and its implementation in nursing. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2017, 10, 596. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, S.B.; Guastello, S.; Hoy, L.; Naylor, M.; Sheridan, S.; Johnston-Fleece, M. Harnessing Evidence and Experience to Change Culture: A Guiding Framework for Patient and Family Engaged Care; NAM Perspectives; Discussion paper; National Academy of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKean, G.L.; Thurston, W.E.; Scott, C.M. Bridging the divide between families and health professionals’ perspectives on family-centred care. Health Expect. 2005, 8, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, M.J.; Edgman-Levitan, S. Shared decision making—The pinnacle of patient-centered care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 366, 780–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmelgarn, A.L.; Glisson, C.; Dukes, D. Emergency room culture and the emotional support component of family-centered care. Child. Health Care 2001, 30, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Li, J.; Bu, X.; Gong, Z.X. The relationship between ethical climate and nursing service behavior in public and private hospitals: A cross-sectional study in China. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinke, C. Examining the role of service climate in health care: An empirical study of emergency departments. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2008, 19, 188–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.E.; Schneider, B. A service climate synthesis and future research agenda. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L. Linking service climate to customer loyalty. Serv. Ind. J. 2015, 35, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; White, S.S.; Paul, M.C. Linking service climate and customer perceptions of service quality: Tests of a causal model. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, C.P.; Baltes, B.B.; Young, S.A.; Huff, J.W.; Altmann, R.A.; Lacost, H.A.; Roberts, J.E. Relationships between psychological climate perceptions and work outcomes: A meta-analytic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 389–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Singh, S.K.; Pereira, V.; Leonidou, E. Cause-related marketing and service innovation in emerging country healthcare: Role of service flexibility and service climate. Int. Mark. Rev. 2020, 37, 803–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, J.L.; Pugh, S.D.; Wiley, J. Service climate effects on customer attitudes: An examination of boundary conditions. J. Acad. Manag. 2004, 47, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, D.; Mashiach-Eizenberg, M.; Vinarski-Peretz, H.; Idilbi, N. Factors Predicting Older Patients′ Family Involvement by Nursing Staff in Hospitals: The View of Hospital Nurses in Israel. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saveman, B.I.; Benzein, E.G.; Engström, Å.H.; Årestedt, K. Refinement and psychometric reevaluation of the instrument: Families’ Importance in Nursing Care–Nurses’ Attitudes. J. Fam. Nurs. 2011, 17, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzein, E.; Johansson, P.; Arestedt, K.F.; Saveman, B.-I. Nurses’ attitudes about the importance of families in nursing care: A survey of Swedish nurses. J. Fam. Nurs. 2008, 14, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöndal, K.; Zoëga, S.; Hafsteinsdottir, J.E.; Olafsdottir, O.A.; Thorvardard Otter, A.B.; Hafsteinsdottir, S.A.; Sveindόttir, H. Attitudes of registered and licensed practical nurses about the importance of families in surgical units: Findings from the landspitali university hospital family nursing implementation project. J. Fam. Nurs. 2014, 20, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verho, H.; Arnetz, J.E. Validation and application of an instrument for measuring patient relatives’ perception of quality of geriatric care. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2003, 15, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Schneider, B.; White, S.S.; Paul, M.C. Too much a good thing: A multiple-constituency perspective on service organization effectiveness. J. Serv. Res. 1998, 1, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B.H. Promoting patient-and family-centered care through personal stories. Acad. Med. 2016, 91, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, M.; Moretz, J.G. Implementing patient- and family-centered care: Part I—Understanding the challenges. Pediatr. Nurs. 2012, 38, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mastro, K.A.; Flynn, L.; Preuster, C. Patient-and family-centered care. A call to action for new knowledge and innovation. J. Nurs. Adm. 2014, 44, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Lee, M.; Jeong, H.; Jeong, M.; Go, Y. Patient-and family-centered care interventions for improving the quality of health care: A review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 87, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, B.R.; Mitchell, M.; Marshall, A. The impact of interventions that promote family involvement in care on adult acute-care wards: An integrative review. Collegian 2018, 25, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelo, M.; Cruz, A.C.; Mekitarian, F.F.P.; Santos, C.C.D.S.D.; Martinho, M.J.C.M.; Martins, M.M.F.P.D.S. Nurses’ attitudes regarding the importance of families in pediatric nursing care. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2014, 48, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhardt, T.; Hallberg, I.R.; Poulsen, I. Nurses’ experience of collaboration with relatives of frail elderly patients in acute hospital wards: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haesler, E.; Bauer, M.; Nay, R. Recent evidence on the development and maintenance of constructive staff family relationships in the care of older people: A report on a systematic review update. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2010, 8, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Liao, H.; Hu, J.; Jiang, K. Missing link in the service profit chain: A meta-analytic review of the antecedents, consequences, and moderators of service climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 237–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, B.; Macey, W.H.; Lee, W.C.; Young, S.A. Organizational service climate drivers of the American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI) and financial and market performance. J. Serv. Res. 2009, 12, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenslade, J.H.; Jimmieson, N.L. Organizational factors impacting on patient satisfaction: A cross sectional examination of service climate and linkages to nurses’ effort and performance. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechinda, P.; Patterson, P.G. The impact of service climate and service provider personality on employees’ customer-oriented behavior in a high-contact setting. J. Serv. Mark. 2012, 25, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I.; O’Neill, C.; Murphy, M.; Costello, T.; O’Shea, R. What does family-centred care mean to nurses and how do they think it could be enhanced in practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 67, 2561–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoulay, E.; Chaize, M.; Kentish-Barnes, N. Involvement of ICU families in decisions: Fine-tuning the partnership. Ann. Intensive Care 2014, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, J.; Bendahan, S.; Jacquart, P.; Lalive, R. On making causal claims: A review and recommendations. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 1086–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.M.; Lance, C.E. What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Principles and Methods; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Report. The Committee for Eradicating and Dealing with Violence in the Health System in Israel. 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.il/he/Departments/publicbodies/committee-violence-prevention (accessed on 20 August 2023). (In Hebrew)

- Health Committee. Knesset of Israel. 2021. Available online: https://main.knesset.gov.il/activity/committees/health/news/pages/briut-23.11.21.aspx (accessed on 20 August 2023). (In Hebrew)

| N | % | M | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender a | Female | 120 | 67.00% | ||

| Male | 58 | 32.40% | |||

| Age b | 23–35 | 63 | 35.20% | 40.6 | 10.5 |

| 36–50 | 67 | 37.40% | |||

| 51 and older | 35 | 19.60% | |||

| Marital Status c | Married | 135 | 75.40% | ||

| Single | 27 | 15.10% | |||

| Divorced | 12 | 6.70% | |||

| Widowed | 3 | 1.70% | |||

| Religion d | Jewish | 66 | 36.90% | ||

| Muslim | 46 | 25.70% | |||

| Christian | 49 | 27.40% | |||

| Druze | 7 | 3.90% | |||

| Education c | Professional training | 23 | 12.80% | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 95 | 53.10% | |||

| Master’s degree | 59 | 33.00% | |||

| Professional position e | Certified nurse, no leadership responsibilities | 141 | 78.80% | ||

| Certified nurse with leadership responsibilities | 34 | 19.00% | |||

| Years in profession | 13.8 | 10.9 | |||

| Job percentages e | Full-time | 119 | 66.50% | ||

| Part-time | 56 | 31.30% |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Nurses’ Collaborative Behavior | 1 | |||||

| 2. Fam-RNC | 0.41 *** | 1 | ||||

| 3. Fam-CP | 0.50 *** | 0.72 *** | 1 | |||

| 4. Fam-B | −0.24 ** | −0.13 * | −0.06 | 1 | ||

| 5. Fam-OR | 0.56 *** | 0.65 *** | 0.69 *** | −0.17 * | 1 | |

| 6. FINC-NA (total) | 0.55 *** | 0.90 *** | 0.87 *** | −0.36 *** | 0.81 *** | 1 |

| 7. Service Climate | 0.35 *** | 0.12 * | 0.30 *** | −0.07 | 0.33 *** | 0.26 *** |

| Predictor Variable | B | S.E | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: | |||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 0.33 | 0.12 | 0.31 | 20.75 | 0.007 |

| Master’s degree | 0.34 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 20.67 | 0.008 |

| Step 2: | |||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 0.27 | 0.1 | 0.26 | 20.77 | 0.006 |

| Master’s degree | 0.19 | 0.1 | 0.17 | 10.86 | 0.065 |

| Fam-RNC | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.05 | −00.49 | 0.627 |

| Fam-CP | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 20.63 | 0.009 |

| Fam-B | −0.10 | 0.04 | −0.16 | −20.61 | 0.01 |

| Fam-OR | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.33 | 30.6 | <0.001 |

| Service Climate | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 20.4 | 0.018 |

| Value of Service Climate | Effect | SE | 95% CI | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean − 1 SD (2.84) | −0.24 | 0.06 | [−0.36, −0.12] | −3.84 | <0.001 |

| Mean (3.43) | −0.14 | 0.04 | [−0.23, −0.06] | −3.39 | <0.001 |

| Mean + 1 SD (4.01) | −0.05 | 0.06 | [−0.16, 0.06] | −0.84 | 0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vinarski-Peretz, H.; Mashiach-Eizenberg, M.; Idilbi, N.; Halperin, D. Service Climate and Nurses’ Collaboration with Families of Older Patients in the Care Process during Hospitalization. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182485

Vinarski-Peretz H, Mashiach-Eizenberg M, Idilbi N, Halperin D. Service Climate and Nurses’ Collaboration with Families of Older Patients in the Care Process during Hospitalization. Healthcare. 2023; 11(18):2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182485

Chicago/Turabian StyleVinarski-Peretz, Hedva, Michal Mashiach-Eizenberg, Nasra Idilbi, and Dafna Halperin. 2023. "Service Climate and Nurses’ Collaboration with Families of Older Patients in the Care Process during Hospitalization" Healthcare 11, no. 18: 2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182485

APA StyleVinarski-Peretz, H., Mashiach-Eizenberg, M., Idilbi, N., & Halperin, D. (2023). Service Climate and Nurses’ Collaboration with Families of Older Patients in the Care Process during Hospitalization. Healthcare, 11(18), 2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182485