Risk Factors Linked to Violence in Female Same-Sex Couples in Hispanic America: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

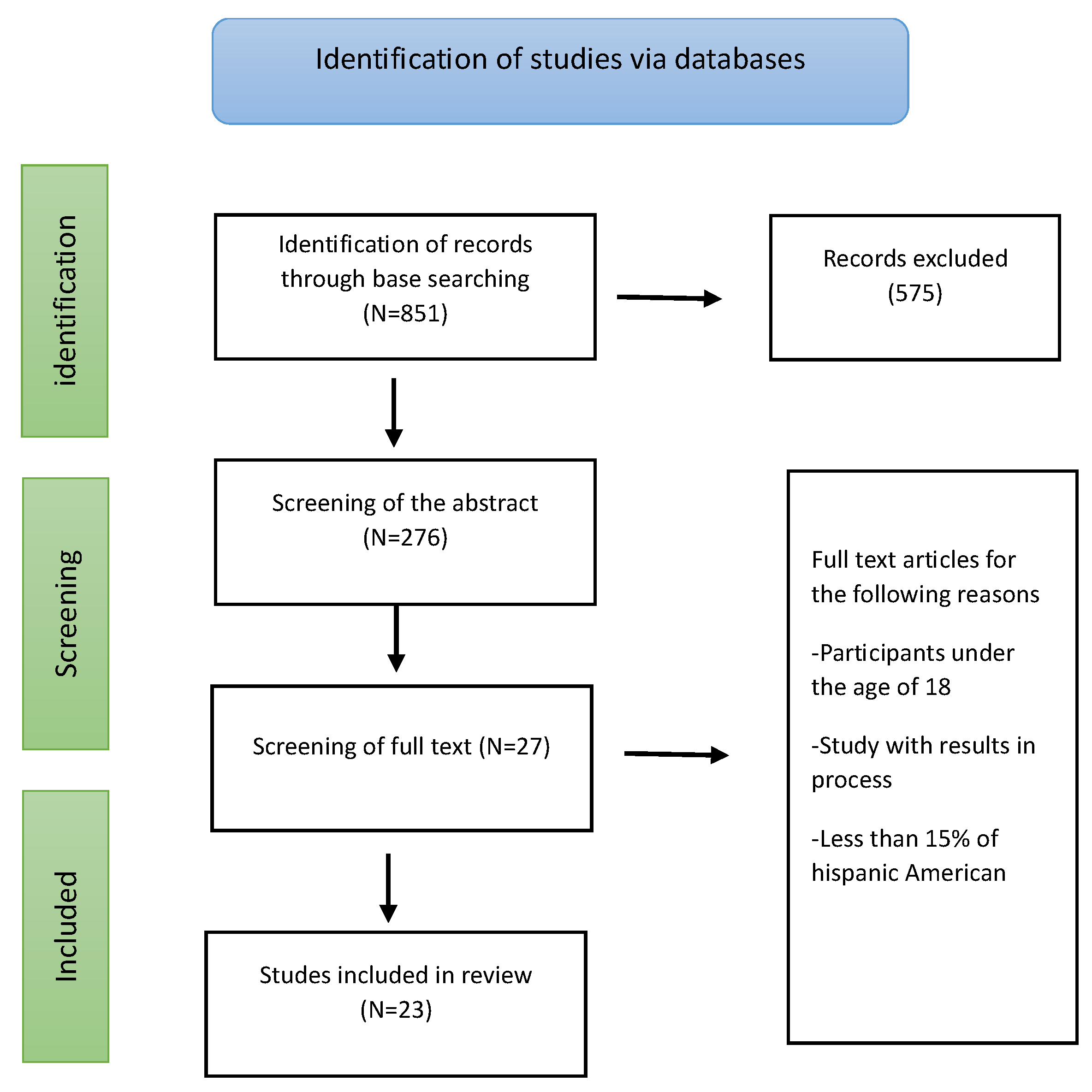

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

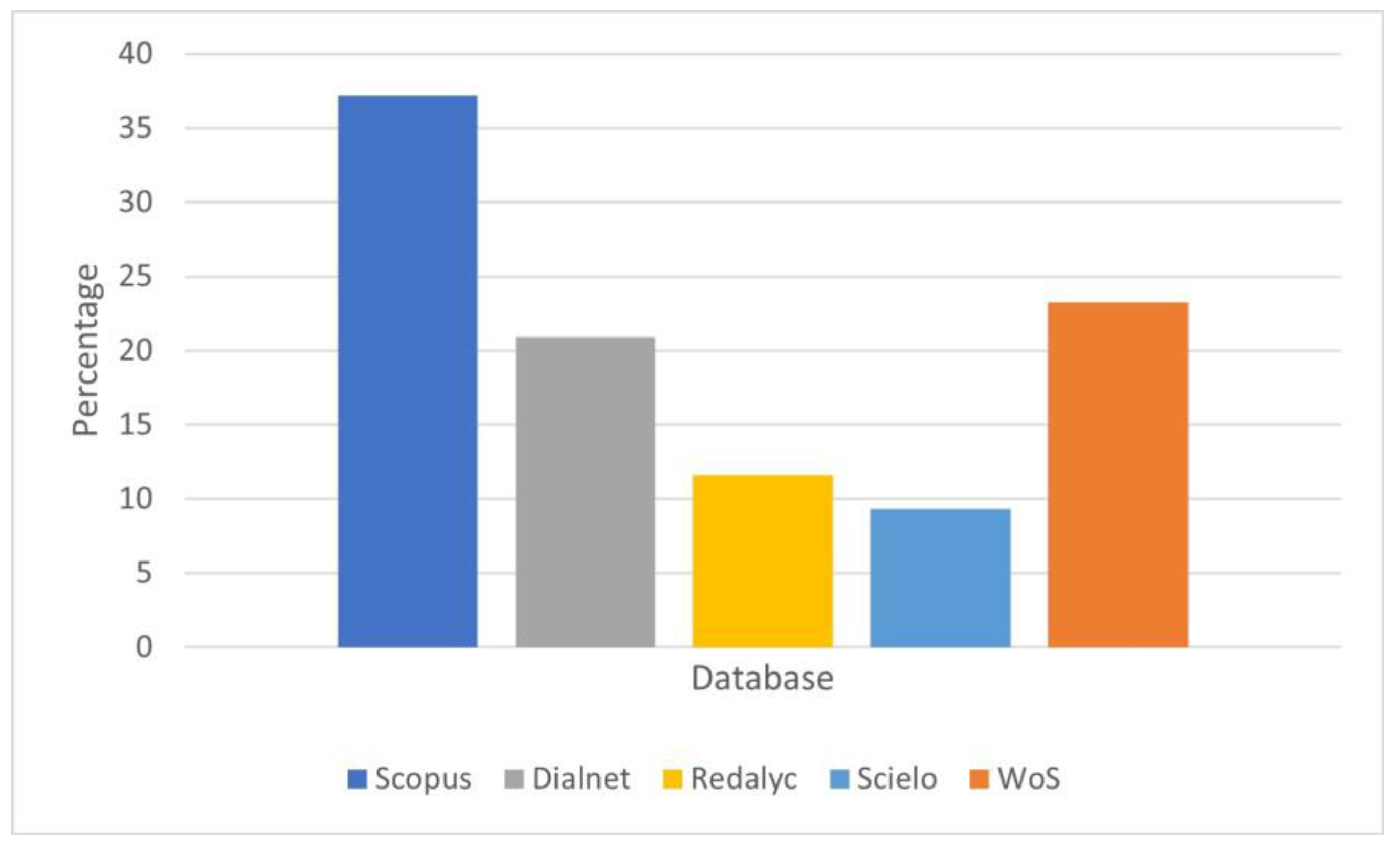

2.2. Search Method

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criterion

- The inclusion criteria:

- 1.

- Studies whose main purpose was to analyze violence in couples.

- 2.

- Studies published between 2000 and 2022.

- 3.

- Studies that included the LGTBIQ+ population as the main sample.

- 4.

- Studies in English and Spanish *.

- 5.

- Journal articles that had undergone peer review (to ensure the quality of the publication).

- 6.

- Studies with a minimum of 15% of participants/a Spanish–American sample *.

- 7.

- Studies that included only participants over 18.

- * Due to these criteria, the study is classified as Hispanic American rather than Latin American, as Portuguese literature was not taken into consideration

- Exclusion criteria (failure to comply with one of these criteria means that the publication is excluded):

- 1.

- Theoretical articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and trials.

- 2.

- Articles in which the main purpose is not to measure IPV.

- 3.

- Articles that do not have a Hispanic American population.

- 4.

- Articles that include participants under 18.

- 5.

- Non-blind peer-reviewed publications.

- 6.

- Articles written in languages other than Spanish or English.

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Analysis and Synthesis of Results

3. Results

3.1. Comparing Studies Focusing on FSSC with Other Intragender Relationships

3.2. Risk Factors

3.2.1. Macro-Social System Level

3.2.2. Exosystem Level

3.2.3. Mesosystem Level

3.2.4. Micro-System Level

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walters, L.; Chen, J.; Breiding, M. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013.

- Breiding, M.; Basile, K.; Smith, S.; Black, M.; Mahendra, R. Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 2.0; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2015.

- Longobardi, C.; Badenes-Ribera, L. Intimate Partner Violence in Same-Sex Relationships and The Role of Sexual Minority Stressors: A Systematic Review of the Past 10 Years. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagdon, S.; Armour, C.; Stringer, M. Adult experience of mental health outcomes as a result of intimate partner violence victimisation: A systematic review. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2014, 5, 24794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristock, J.L. No More Secrets. Violence in Lesbian Relationships; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Stiles-Shields, C.; Carroll, R.A. Same-Sex Domestic Violence: Prevalence, Unique Aspects, and Clinical Implications. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2015, 41, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.M.; Sylaska, K.M. Reactions to Participating in Intimate Partner Violence and Minority Stress Research: A Mixed Methodological Study of Self-Identified Lesbian and Gay Emerging Adults. J. Sex Res. 2015, 53, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langenderfer-Magruder, L.; Whitfield, D.L.; Walls, N.E.; Kattari, S.K.; Ramos, D. Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence and Subsequent Police Reporting Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Adults in Colorado: Comparing Rates of Cisgender and Transgender Victimization. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 31, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsam, K.F.; Szymanski, D.M. Relationship quality and domestic violence in women’s same-sex relationships: The role of minority stress. Psychol. Women Q. 2005, 29, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, N.; Lynch, I. ‘You have to bow right here’: Heteronormative scripts and intimate partner violence in women’s same-sex relationships. Cult. Health Sex. 2017, 20, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, L.; Henry, R.; Smith, E.; Aguayo, A.; Viridiana, B.; Barajas, R.; Perrin, P. Discrimination and Intimate Partner Violence Victimization and Perpetration Among a Convenience Sample of LGBT Individuals in Latin America. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 36, NP8520–NP8537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, T.; Rollè, L. Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration Among Sexual Minority People and Associated Factors: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2023, 20, 886–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita, S.; Vila, M.; Carpente, J. Determinación de factores de riesgo Pita. Cad. Atención Primaria 2002, 48, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. La Ecologia del Desarrollo Humano. Experimentos en Entornos Naturales y Diseñados; Paidós Ibérica: Barcelona, Spain, 1987; pp. 231–281. [Google Scholar]

- Frías, S.M. Ámbitos y formas de violencia contra mujeres y niñas: Evidencias a partir de las encuestas. Acta Sociol. 2014, 65, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, M.; Alday, A.; Aurellano, A.; Escala, S.; Hernandez, P.; Matienzo, J.; Panaguiton, K.; Tan, A.; Zsila, A. Minority Stressors and Attitudes Toward Intimate Partner Violence among Lesbian and Gay Individuals. Sex. Cult. 2023, 27, 930–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balik, C.; Bilgin, H. Experiences of Minority Stress and Intimate Partner Violence Among Homosexual Women in Turkey. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 36, 8984–9007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ard, K.L.; Makadon, H.J. Addressing intimate partner violence in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 930–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woulfe, J.M.; Goodman, L.A. Identity Abuse as a Tactic of Violence in LGBTQ Communities: Initial Validation of the Identity Abuse Measure. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 36, 2656–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.H.; Peterson, N.A.; Cheng, Y.-J.; Dalley, L.M.; Flowers, K.M. A Systematic Review of Standardized Assessments of Couple and Family Constructs in GLBT Populations. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2020, 16, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology, Qualitative Research in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, J.; Escartín, J.; Longares, L.; Rodríguez-Carballeira, Á. Sociodemographic characteristics of gay and lesbian victims of intimate partner psychological abuse in Spain and Latin America/Características sociodemográficas de gais y lesbianas víctimas de abuso psicológico en pareja en España e Hispanoamérica. Rev. Psicol. Soc. 2018, 33, 240–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, S.C.; Robles, G.; Stephenson, R.; Starks, T.J. Relationship Power and Intimate Partner Violence in Sexual Minority Male Couples. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 37, NP671–NP695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, L.; Lara, M. HIV as a means of materializing Gender Violence and violence in same-sex couples. Enferm. Glob. 2021, 62, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Pacheco, J.; Rey-García, P.; Ibarra-Mojica, A.; Luzardo-Briceño, M. Violencia intragénero entre parejas homosexuales en universitarios de Bucaramanga, Colombia. Univ. y Salud 2021, 23, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longares, L.; Escartín, J.; Barrientos, J.; Rodríguez-Carballeira, Á. Insecure Attachment and Perpetration of Psychological Abuse in Same-Sex Couples: A Relationship Moderated by Outness. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2018, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.; Kaighobadi, F.; Stephenson, R.; Rael, C.; Sandfort, T. Associations between Alcohol Use and Intimate Partner Violence among Men Who Have Sex with Men. LGBT Health 2016, 3, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, R.; Khosropour, C.; Sullivan, P. Reporting of Intimate Partner Violence among Men Who Have Sex with Men in an Online Survey. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2010, 11, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reyes, F.; Rodríguez, J.R.; Malavé, S. Manifestaciones de la violencia doméstica en una muestra de hombres homosexuales y mujeres lesbianas puertorriqueñas. Interam. J. Psychol. 2005, 39, 449–456. [Google Scholar]

- Loveland, J.E.; Raghavan, C. Near-Lethal Violence in a Sample of High-Risk Men in Same-Sex Relationships. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2014, 1, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, E.; McKirnan, D.J. Intimate partner abuse among gay and bisexual men: Risk correlates and health outcomes. J. Urban Health 2007, 84, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gómez, F.; Barrientos Delgado, J.; Guzmán González, M.; Cárdenas Castro, M.; Bahamondes Correa, J. Violencia de pareja en hombres gay y mujeres Lesbianas Chilenas: Un estudio exploratorio. Interdisciplinaria 2017, 34, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, S.; Toro-Alfonso, J. Description of a domestic violence measure for Puerto Rican gay males. J. Homosex. 2005, 50, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, E.M.; Rozee, P.D. Knowledge about heterosexual versus lesbian battering among lesbians. Intim. Betrayal Domest. Violence Lesbian Relatsh. 2001, 23, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, G.S.; Wolfe, V.A. Battered gay men: An exploration of abuse, help seeking, and why they stay. J. Homosex. 2000, 39, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldivia, C.; Faúndez, B.; Sotomayor, S.; Cea, F. Violencia íntima en parejas jóvenes del mismo sexo en Chile. Última Década 2017, 25, 184–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro-Alfonso, J.; Rodríguez-Madera, S. Domestic violence in Puerto Rican gay male couples: Perceived prevalence, intergenerational violence, addictive behaviors, and conflict resolution skills. J. Interpers. Violence 2004, 19, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S. Perceptions of psychological intimate partner violence: The influence of sexual minority stigma and childhood exposure to domestic violence among bisexual and lesbian women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.A. Caracterización de las representaciones sociales de la violencia intragénero en parejas de hombres gay. Caso: Ciudad de Temuco-Chile. Hum. Rev. Int. Humanit. Rev. Rev. Int. Humanidades 2022, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, K.; McNeeley, M.; Collins, S. “Same-Sex Relationship in a Straight World”: Individual and Societal Influences on Power and Control in Young Men’s Relationships. J. Interpers. Violence 2015, 30, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Ayala, D. Intimidad y las múltiples manifestaciones de la violencia doméstica entre mujeres lesbianas. Salud Soc. 2011, 2, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondan, L.-B.; Rojas, S.; Cruz-Manrique, Y.R.; Malvaceda-Espinoza, E.L. Violencia Íntima de Pareja, en parejas lesbianas, gais y bisexuales de Lima Metropolitana. Rev. Investig. Psicol. 2022, 25, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronzón-Tirado, R.C.; Rey, L.; del Pilar González-Flores, M. Modelos parentales y su relación con la violencia en las parejas del mismo sexo. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Niñez Juv. 2017, 15, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez-Santaya, P.; Walters, A.S. Intimate Partner Violence Within Gay Male Couples: Dimensionalizing Partner Violence Among Cuban Gay Men. Sex. Cult. 2011, 15, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, E.; Panadero, S.; Bonilla, E.; Vásquez, R.; Vázquez, J.J. Influencia del apoyo social en el mantenimiento de la convivencia con el agresor en víctimas de violencia de género de León (Nicaragua). Inf. Psicol. 2018, 18, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.M. Lesbian intimate partner violence: Prevalence and dynamics. J. Lesbian Stud. 2002, 6, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantera, L. Aproximación empírica a la agenda oculta en el campo de la violencia en la pareja. Psychosoc. Interv. 2004, 13, 219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Cantera, L.; Gamero, V. La violencia en la pareja a la luz de los estereotipos de género. Psico 2007, 38, 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos, J.; Rodríguez Carballeira, Á.; Escartín Solanelles, J.; Longares, L. Violencia en parejas del mismo sexo:revisión y perspectivas actuales/Intimate same-sex partner violence: Review and outlook. Rev. Argent. Clínica Psicol. 2016, XXV, 289–298. [Google Scholar]

- Rollè, L.; Giardina, G.; Caldarera, A.M.; Gerino, E.; Brustia, P. When intimate partner violence meets same sex couples: A review of same sex intimate partner violence. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. Gender-role implications on same-sex intimate partner abuse. J. Fam. Violence 2008, 23, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, B.; Terrance, C. Perceptions of domestic violence in lesbian relationships: Stereotypes and gender role expectations. J. Homosex. 2010, 57, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristock, J.L. Relationship Violence in Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual/Transgender/Queer [LGBTQ] Communities Moving Beyond a Gender-Based Framework; Violence Against Women Online Resources: Harrisburg, PA, USA, 2005; pp. 1–19. Available online: http://www.mincava.umn.edu/documents/lgbtqviolence/lgbtqviolence.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- National Center on Domestic & Sexual Violence. Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Trans Power and Control Wheel; National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence: Austin, TX, USA, 2014; Available online: http://www.ncdsv.org/images/%0ATCFV_glbt_wheel.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Villarreal, A. Women’s Employment Status, Coercive Control, and Intimate Partner Violence in Mexico. J. Marriage Fam. 2007, 69, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puentes-Martinez, A.; Ubillos-Landa, S.; Echeburúa, E.; Páez-Rovira, D. Factores de riesgo asociados a la violencia sufrida por la mujer en la pareja: Una revisión de meta-análisis y estudios recientes. Ann. Psychol. 2016, 32, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, J. La perspectiva ecológica. In Introducción a la Psicología Comunitaria; Editorial Paidós: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2004; pp. 99–134. [Google Scholar]

- Badenes-Ribera, L.; Bonilla-Campos, A.; Frias-Navarro, D.; Pons-Salvador, G.; Monterde-i-Bort, H. Intimate partner violence in self-identified lesbians: A systematic review of its prevalence and correlates. Trauma Violence Abus. 2015, 17, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subirana-Malaret, M.; Gahagan, J.; Parker, R. Intersectionality and sex and gender-based analyses as promising approaches in addressing intimate partner violence treatment programs among LGBT couples: A scoping review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1644982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messinger, A.M. Bidirectional Same-Gender and Sexual Minority Intimate Partner Violence. Violence Gend. 2018, 5, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, C.L.; Slavin, T.; Hilton, K.L.; Holt, S.L. Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Services and Resources in Los Angeles: Issues, Needs, and Challenges for Assisting Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Clients. Health Promot. Pract. 2013, 14, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przeworski, A.; Piedra, A. The Role of the Family for Sexual Minority Latinx Individuals: A Systematic Review and Recommendations for Clinical Practice. J. GLBT Fam. Stud. 2020, 16, 211–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristock, J.L. Exploring Dynamics of Abusive Lesbian Relationships: Preliminary Analysis of a Multisite, Qualitative Study. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2003, 31, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, N.; Perrin, N.; Hanson, G.; Bloom, T.; Gardner, E.; Campbell, J.C. Risk for reassault in abusive female same-sex relationships. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klostermann, K.; Kelley, M.L.; Milletich, R.J.; Mignone, T. Alcoholism and partner aggression among gay and lesbian couples. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2011, 16, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, E.; Lloret, I. La violencia de género. In Concepto Jurídico de Violencia de Género; Editorial UOC: Barcelona, Spain, 2007; pp. 41–80. [Google Scholar]

- Randle, A.A.; Graham, C.A. A Review of the Evidence on the Effects of Intimate Partner Violence on Men. Psychol. Men Masculinity 2011, 12, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Molnar, B.E.; Feurer, I.D.; Appelbaum, M. Patterns and mental health predictors of domestic violence in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2001, 24, 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Marek, E.N.; Cafferky, B.; Dharnidharka, P.; Mallory, A.B.; Dominguez, M.; High, J.; Stith, S.M.; Mendez, M. Effects of Childhood Experiences of Family Violence on Adult Partner Violence: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2015, 7, 498–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselschwerdt, M.L.; Savasuk-Luxton, R.; Hlavaty, K. A Methodological Review and Critique of the “Intergenerational Transmission of Violence” Literature. Trauma Violence Abus. 2019, 20, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, S.; Yonas, M.A.; Silvestre, A.J.; Burke, J.G. Intimate Partner Violence among HIV Positive Persons in an Urban Clinic. AIDS Care 2021, 22, 1536–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, A.; Ghandour, R.M.; Burke, J.G.; Mahoney, P.; McDonnell, K.A.; O’Campo, P. HIV/AIDS and intimate partner violence: Intersecting women’s health issues in the United States. Trauma Violence Abus. 2008, 8, 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalichman, S.; Rompa, D. Sexually coerced and noncoerced gay and bisexual men: Factors relevant to risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. J. Sex Res. 1995, 32, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Method | Country of First Author | Origin of Participants | Sexual Orientation/Sexual Practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrientos et al. [25] | Quantitative | Chile | Spain 399 (63.3%) Mexico 130 (20.6%) Venezuela 57 (9%) Chile 44 (7%) | Lesbians 285 (45.2%) Gays 345 (54.7%) |

| Bosco et al. [26] | Quantitative | USA | White E/C 225 (66.4%) Black/Afro 27 (8.0%) Hispanos 51 (15.0%) Other 36 (10.6%) | Gays 304 (87.7%) Bisexual men 35 (10.3%) |

| L. Rodríguez & Lara. [27] | Quantitative | Mexico | Mexico 277 (100%) | Homosexual 128 (64.6%) Heterosexual 49 (24.7%) Bisexuals 20 (10.1%) Other 1 (0.5%) |

| Redondo-Pacheco et al. [28] | Quantitative | Colombia | Colombia 132 (100%) | Gays 93 (70.5%) Lesbians 39 (29.5%) |

| Longares et al. [29] | Quantitative | Spain | Spain (44.6%) Mexico (20%) Venezuela (8.5%) Chile (8.5%) | Gays147 (48.2%) Lesbians 112 (36.7%) Pansexual or bisexual 46 (15.1%) |

| Davis et al. [30] | Quantitative | USA | White E/C 85 (45%) Asian 6 (3.2%) Hispano 39 (20.6%) Black/Afro 49 (25.9%) Other 9 (4.8%) | MSM 189 (100%) |

| Stephenson et al. [31] | Quantitative | USA | White E/C 191 (47.67%) Black/Afro 60 (14.86%) Hispanic 151 (37.47%) | Bisexual 77 (19.07%) Homosexual 325 (80.93%) |

| Reyes et al. [32] | Quantitative | Puerto Rico | Puerto Rico 201 (100%) | Gays 124 (61.7%) Lesbians 66 (32.8%) Bisexual women 6 (3%) Bisexual men 5 (2.5%) |

| Loveland & Raghavan. [33] | Quantitative | USA | White E/C (8.1%) Black/Afro (49.3%) Hispanos (21.3%) Other (21.3%) | Gay 24 (17%) Bisexual men 32 (24.4%) Not identified 22 (16.3%) Heterosexual men 24 (17.8%) MSM 34 (24.5%) |

| Houston & McKirnan. [34] | Quantitative | USA | White E/C 182 (22.4%) Black/Afro 419 (51.3%) Hispanos 133 (16.3%) Asian/Pacific islanders or other ethnicities 82 (10%) | Gays 609 (74.5%) Bisexual men 104 (12.7%) MSM 104 (12.8%) |

| Gómez et al. [35] | Quantitative | Chile | Chile 467 (100%) | Lesbians 199 (42.6%) Gays 268 (57.4%) |

| S. Rodríguez & Toro-Alfonso. [36] | Quantitative | Puerto Rico | Puerto Rico 302 (100%) | Gays 245 (81%) Bisexual men 57 (19%) |

| McLaughlin & Rozee. [37] | Quantitative | USA | White E/C 151 (51%) Black/Afro 39 (13%) Hispanos 59 (20%) Other 27 (9%) Asian/ Pacific islanders 18 (6%) American Indians 3 (1%) | Lesbians 256 (86.2%) Bisexual women 41 (13.8%) |

| Merrill & Wolfe. [38] | Quantitative | USA | White E/C 15 (29%) Black/Afro 15 (29%) Hispanos 10 (19%) Others 4 (7%) American Indians 2 (4%) | Gays 50 (96%) Bisexual men 2 (4%) |

| Saldivia et al. [39] | Quantitative | Chile | Chile 631 (100%) | Men 222 (35.2%) Women 409 (64.8%) |

| Toro-Alfonso & Rodríguez-Madera. [40] | Quantitative | Puerto Rico | Puerto Rico 200 (100%) | Gays 165 (83%) Bisexual men 35 (17%) |

| Islam. [41] | Quantitative | USA | White E/C 126 (68.9%) Black/Afro 20 (10.9%) Hispanos 28 (15.3%) Other non-Hispanic 8 (4.4%) | Lesbians 79 (43.1%) Bisexual women 104 (56.9%) |

| Franco. [42] | Qualitative | Chile | Chile 20 (100%) | Gays 20 (100%) |

| Kubicek et al. [43] | Qualitative | USA | White E/C 15 (15%) Black/Afro 25 (25%) Hispanos 35 (35%) Asian/ Pacific islanders 7 (7%) Multiethnic 19 (19%) | Gays/MSM 72 (72%) Bisexual men 27 (27%) |

| López & Ayala. [44] | Qualitative | Puerto Rico | Puerto Rico 7 (100%) | Lesbians 6 (85%) |

| Rondan et al. [45] | Qualitative | Peru | Peru 17 (100%) | Lesbians 3 (17.6%) Gays 8 (47%) Bisexual women 6 (35.3%) |

| Ronzón-Tirado et al. [46] | Qualitative | Mexico | Mexico 15 (100%) | Gays 8 (53.3%) Lesbians 6 (40%) Bisexual woman 1 (6.6%) |

| Téllez-Santaya & Walters. [47] | Mixed method | Spain | Cuba 70 (100%) | Homosexuals 70 (100%) |

| Source | Goal | Power Relationships | Stress of Minorities | Professional Training | Social Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [29] | To study the influence of insecure attachment style on the perpetration of psychological abuse in same-sex couples, and the moderating role of the level of externality as an antecedent variable of psychological abuse perpetration. | Lack of power and control is reacted to with high levels of insecure attachment. | Outness is linked to social support and the absence of social support can act as a stressor. | Not applicable | Lack of social support can act as a stress factor. |

| [32] | To analyze the expressions of domestic violence in the lesbian, bisexual and transgender homosexual population (LGBT) in Puerto Rico. | Not applicable | Homosexual men deny or minimize violence because of social stigma. | Promote awareness in services to avoid homophobic and lesbophobic reactions | Not applicable |

| [35] | To describe the experiences of partner violence (PV) in a sample of gay and lesbian women. | Not applicable | Not applicable | Heteronormative laws that do not adequately consider these cases. | Not applicable |

| [37] | Exploring the idea that the lesbian community may not be conceptualizing violence in lesbian relationships as domestic violence. | Makes use of homophobia and coming out to maintain power and control. | Minority stress intersects with support networks, as the aggressor isolates from their networks and also threatens with outness | The importance of training, research, and community practices in social assistance institutions to address violence in same-sex couples | Minority stress-related support |

| [39] | To characterize the type of violence in young same-sex couples in Chile during 2016. | Not applicable | Internalized heterosexism leads to rejection of oneself and one’s partner. | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| [41] | To examine perceptions of psychological IPV, sexual minority stigma, and childhood exposure to domestic violence among sexual minority women residing in the US. | Not applicable | Internalized stigma correlates significantly to women’s psychological IPV. | Not applicable | An important aspect to break out of violence. |

| [44] | To explore the experiences of domestic violence in a group of lesbian women in Puerto Rico, and to identify the obstacles and facilitators in their processes of help and support as victims of this problem. | Not applicable | Internalized oppression arises from external prejudices and stereotypes. | Lack of interest in training due to homophobia | Uses the isolation of the victim from her support networks as a control mechanism. At the social level there are no support networks due to exclusion and marginalization by government policies. |

| [45] | To analyze the perceptions of intimate partner violence (IPV) among lesbians, gays and bisexuals (LGB) in metropolitan Lima. | Power is linked to the control produced by jealousy based on emotional insecurity. | Emotional insecurity due to the lack of acceptance of other orientations, which implies not making oneself visible for fear of the consequences. | Not applicable | Social support is not felt due to homophobia or continued isolation from the partner. |

| [46] | Describing the elements associated with violence in gay and lesbian relationships. | A means to solve conflicts | Outness triggered the rupture of close ties, generating a progressive isolation so that the only person it contains is the partner. | Questioning heteronormative models in campaigns related to partner violence | The loss of informal support was influenced by coming out of the closet. |

| Source | HIV or STI | Substance Consumption | Depression/ Suicidal Ideas | Sociodemographic Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [25] | Not applicable | In gay victims of violence, alcohol consumption is higher. No differences were found in lesbians. Consumption of other substances was not significant. | Variable suicidal ideation was not significant between victims and non-victims. Not relevant in lesbians | There are no significant differences in age and professional status between gay victims and non-victims. |

| [28] | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | There are no significant differences in sociodemographic variables and IPV |

| [32] | Not applicable | Consumption of alcohol and other substances in IPV episodes was higher in lesbians. | Not applicable | Education is not significantly related to IPV. |

| [35] | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | More education, less victimization. |

| [39] | HIV is not recognized as a problem in female-to-female relationships. | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| [43] | Not applicable | Alcohol present in childhood violence, drinking father and aggressor. Within the couple, it was present in episodes of IPV | Not applicable | Not applicable |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garay-Villarroel, L.; Castrechini-Trotta, A.; Armadans-Tremolosa, I. Risk Factors Linked to Violence in Female Same-Sex Couples in Hispanic America: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2456. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11172456

Garay-Villarroel L, Castrechini-Trotta A, Armadans-Tremolosa I. Risk Factors Linked to Violence in Female Same-Sex Couples in Hispanic America: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2023; 11(17):2456. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11172456

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaray-Villarroel, Leonor, Angela Castrechini-Trotta, and Immaculada Armadans-Tremolosa. 2023. "Risk Factors Linked to Violence in Female Same-Sex Couples in Hispanic America: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 11, no. 17: 2456. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11172456

APA StyleGaray-Villarroel, L., Castrechini-Trotta, A., & Armadans-Tremolosa, I. (2023). Risk Factors Linked to Violence in Female Same-Sex Couples in Hispanic America: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 11(17), 2456. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11172456