Utilizing the Social Determinants of Health Model to Explore Factors Affecting Nurses’ Job Satisfaction in Saudi Arabian Hospitals: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Question

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

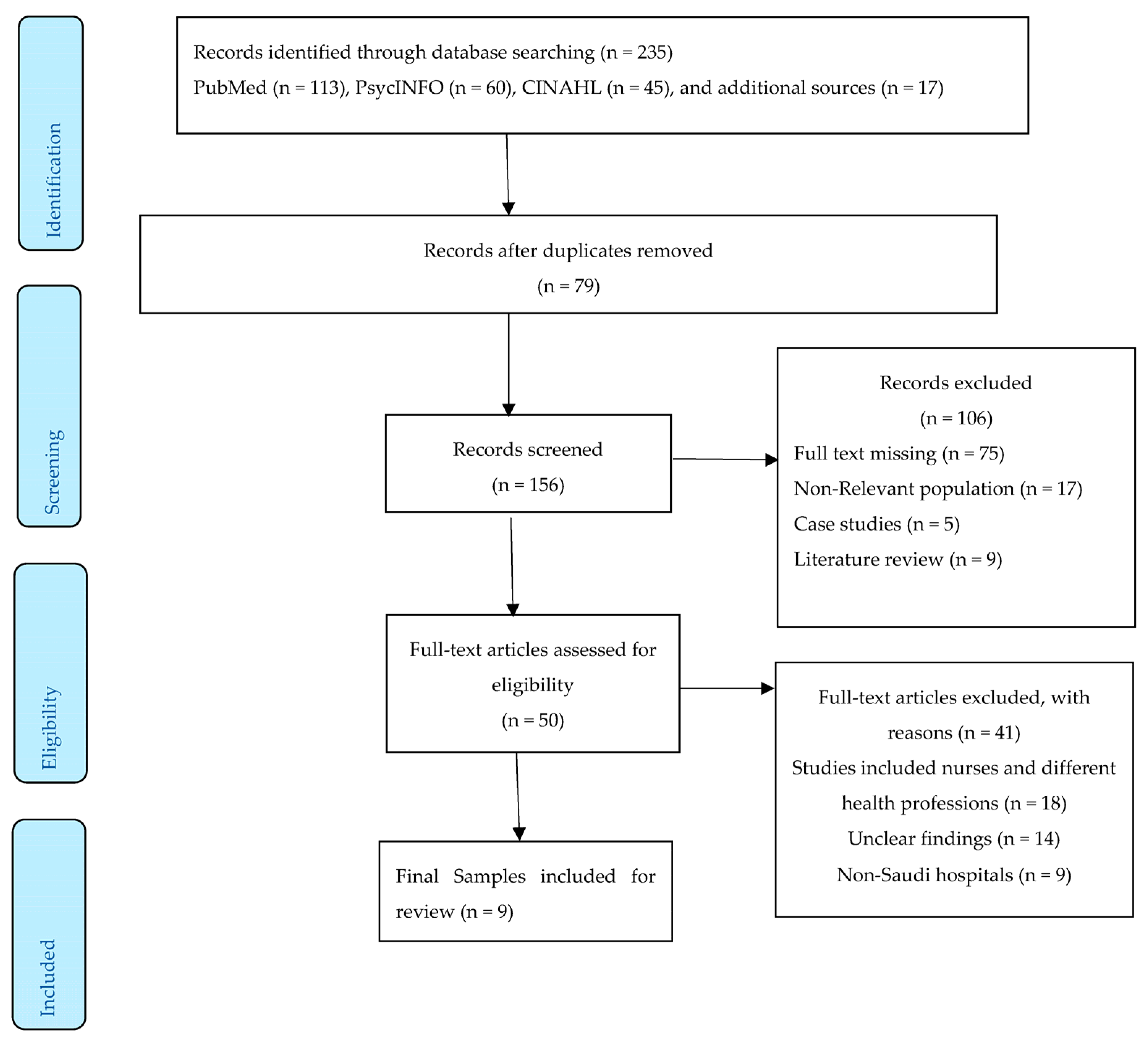

2.3. Search Outcomes

2.4. Data Abstraction

| Authors, Year | Country/Time Frame | Study Design | Sample Size/Population Characteristics | Determinants | Key Findings | SDOH Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [36] | Saudi Arabia March 2015 to March 2016. (Riyadh) | A cross-sectional survey. Tool Used: A self-administered questionnaire | The study was conducted on (n = 364 nurses) working at two different tertiary hospitals in Riyadh city namely King Fahad Medical City (KFMC) and King Faisal Specialized Hospitals (KFSH). Male: 35 (9.6%) Female: 329 (90.4%) Ages: between 22 and 51. Nationality: Saudi (n = 9), and non-Saudi (n = 355) | -Years of experience. -Monthly income. -Gender | There was a statistically significant difference between satisfactory nurse status and years of nursing experience with (p = 0.025). Based on logistic regression analysis there was statistically significant difference between nurses’ satisfaction and those receive less than 5000 and 5000–10,000 Saudi Riyal with (p < 0.001). There were significant differences to suggest that the proportion of females’ nurses (94.8%) had intention to turnover more than male nurses (85.7%) and p value = 0.031. | -Education Access and Quality. -Economic Stability. -Social and Community Context. |

| [37] | Saudi Arabia 2023 (Makkah Region) | Quantitative cross-sectional study. Tool Used: A self-administered questionnaire | The study conducted on (n = 77 nurses) in the National Guard PHCs in the Makkah region, Saudi Arabia. Male: 54 (70%) Female: 23 (30%) Ages: 20 to over 50. Nationality: Saudi (n = 49), and non-Saudi (n = 18) | -Income level. | The mean satisfaction score for those receive < 10,000 SR (M = 3.04, SD = 1.07) is lower than those receive > 10,000 SR (M = 3.11, SD = 0.79). The estimated mean satisfaction score is 0.07. (p = 0.74) No significant difference. | -Economic Stability. |

| [38] | Saudi Arabia 30 May to 15 June 2020. (Hail Region) | Cross-sectional descriptive study design Tool Used: An online self-reported questionnaire | A total of 639 non-Saudi nurses participated from eight tertiary hospitals under the Ministry of Health in this study. Male: 17 (2.7%) Female: 622 (97.3%) Ages: 20 to over 50. | -Wages structure. -Level of education. -Years of experience. -Gender. | In terms of wages, the mean satisfaction score of nurses who had diploma holders (M = 3.4, SD = 0.9) is lower than that those who bachelors and other higher degrees (M = 3.9, 0.9). The estimated mean difference is 0.5. (p < 0.001). Significant difference. The mean score of intention to turnover of nurses who had diploma holders (M = 3.1, SD = 1.0) is lower than that of those who had bachelors and other higher degrees (M = 4.0, SD = 0.9). The estimated mean difference is 0.9. (<0.001). Significant difference. The results revealed that the foreign nurses who have experience for 0–4 years in tertiary hospitals were less satisfied (0.002) than other nurses who have long experience range from 5–10 years. The mean score of intention to turnover for male nurses (M = 3.2, SD = 1.0) is higher than for female nurses (M = 2.6, SD = 1.0). The estimated mean is 0.6. (p = 0.042). Significant difference. | -Economic Stability. -Education Access and Quality. -Social and Community Context. |

| [39] | Saudi Arabia 2018 (Tabuk Region) | Study applied a combination of descriptive, correlational, and cross-sectional analysis. Tool Used: A job satisfaction survey | A total of 190 critical care nurses at King Khalid Hospital in Saudi Arabia were recruited in this study. Male: 25 (13%) Female 165 (87%) Ages: 20 to over 50. Nationality: Not determined. | -Level of education. -Gender. | -The difference in the level of satisfaction was not statistically significant by the level of education (diploma, bachelor, and master) (p = 0.83). -There is no significant difference between males and females on the level of job satisfaction (p = 0.3). | -Education Access and Quality. -Social and Community Context. |

| [40] | Saudi Arabia 2022 (Hail Region) | A cross-sectional study Tool Used: Anonymous self-administered questionnaire | The study conducted in two large public hospitals in Hail City on 196 nurses. Male: 2 (1%) Female: 194 (99%) Ages: 18 to over 55. Nationality: Non-Saudi nurses. | -Pay. | Based on multiple linear regression tests, factor found to be one of the most significant causes of expatriate nursing turnover is pay, (p = 0.022). | -Economic Stability. |

| [20] | Saudi Arabia Between April and May 2018 (Riyadh) | Cross-sectional study. Tool Used: A self-administered structured questionnaire | Participants recruited from two public hospitals (n = 318) nurses. Male: 34 (10.7%). Female: 284 (89.3%). Ages: Mean 29.05 years old (SD = 3.30). Nationality: Saudi (n = 135), non-Saudi (n = 183). | -Marital status. -Nationality. | The mean score of intention to leave for single nurses (M= 3.27, SD = 0.68) is higher than for married nurses (M= 2.71, SD = 0.812). The estimated mean is 0.56. (p < 0.001). Significant difference. The mean score of intention to leave for non-Saudi nurses (3.34) is higher than for Saudi nurses (2.56). The estimated mean is 0.78. | -Neighborhood and Built Environment. -Social and Community Context. |

| [41] | Saudi Arabia Between April and May 2019 (Dammam) | Quantitative cross-sectional descriptive study. Tool Used: The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire | A number of (n = 382) nurses working in a public hospital in Dammam city in Saudi Arabia were recruited in this study. Male: 45 (13.4%). Female: 292 (86.6%). Ages: 20 to over 40. Nationality: Saudi (n = 286), and non-Saudi (n = 51). | -Nationality. -Salary. | There was a significant difference in job satisfaction between Saudi and non-Saudi nurses. The mean satisfaction score of non-Saudi nurses (3.47) is 0.21 higher that than in Saudi nurses (3.26). There is no significant difference between job satisfaction and monthly salary (p = 0.038). | -Social and Community Context. -Economic Stability. |

| [42] | Saudi Arabia 2014 (Riyadh) | Cross sectional study. Tool Used: A self-administered questionnaire | A total of (n = 723) participated from a tertiary medical care center in Riyadh City. Male: 76 (10%). Female: 647 (89.5%). Ages: 30 to over 50. Nationality: Saudi (n = 46), non-Saudi (n = 677). | -Gender. -Nationality. -Level of education. -Salary. | The mean satisfaction score in male (103.43 ± 11.3) is lower than that in female (105.39 ± 8.2). The estimated mean difference is 1.96. (p = 0.15). No significant difference. The mean satisfaction score in Saudi nurses (102.9 ± 10.4) is lower than that in non-Saudi nurses (105.3 ± 8.5). The estimated mean difference is 2.4. The mean satisfaction score of those who have PhD (85.6 + 9.4) is lower than those who have Diploma (106.1 ± 8.5) and Bachelor’s (105.02 ± 8.4) (p < 0.001). Significant difference. The mean satisfaction score of nurses who were unsatisfied with payment (99.3 ± 9.3) is lower than that those who were very satisfied (109.5 ± 6.9). The estimated mean difference is 10.2. (<0.001). Significant difference. | -Social and Community Context. -Education Access and Quality. |

| [43] | Saudi Arabia 2022 (Riyadh) | Cross-sectional research design. Tool Used: Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire and Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index | A total of (n = 500) registered nurses working in five public hospitals in Riyadh. Male: 335 (67%) Female: 129 (25.8%) Do not want to disclose: 36 (7.2%) Nationality: Not determined. | -Gender. -Education. | The median job satisfaction score in those who did not want to disclose their gender (MD = 390.54) is higher compared to those who disclosed their gender as males (MD = 242.71) and females (MD = 231.66). (p < 0.001). Significant difference. The median job satisfaction score in those who had diploma holders (MD = 279.91) is higher compared to those who had bachelor (MD = 246.92) and postgraduate (MD = 148.29). (p < 0.001). Significant difference. | -Social and Community Context. Education Access and Quality. |

2.5. Data Synthesis

2.6. Quality Appraisal

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2. Participants and SDOH Domains Assessed

3.3. Methods Used to Assess

3.4. Pay and Nurses’ Job Satisfaction

3.5. Job Satisfaction and Gender Differences

3.6. The Impact of Professional Experience on Nurses’ Level of Job Satisfaction

3.7. The Association between Nationality and Nurses Job Satisfaction

3.8. Job Satisfaction of Nurses by Education Level

3.9. Marital Status

4. Discussion

4.1. Pay and Nurses’ Job Satisfaction

4.2. Job Satisfaction and Gender Differences

4.3. The Impact of Professional Experience on Nurses’ Level of Job Satisfaction

4.4. Nationality and Nurses Job Satisfaction

4.5. Job Satisfaction of Nurses by Education Level

4.6. Marital Status

4.7. Strengths and Weaknesses

4.8. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schermerhorn, J.R., Jr.; Osborn, R.N.; Uhl-Bien, M.; Hunt, J.G. Organizational Behavior; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aziri, B. Job Satisfaction: A Literature Review. Manag. Res. Pract. 2011, 3, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, P.; Parsons, V.; Dietz, E. Nurse Practitioner’s Characteristics and Job Satisfaction. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2006, 18, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, F.; Mausner, B.; Snyderman, B. The Motivation to Work, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 1959; pp. 15–157. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Motivation through the Design of Work: Test of a Theory. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1976, 16, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Sochalski, J.; Lake, E.T. Studying Outcomes of Organizational Change in Health Services. Med. Care 1997, 35, NS6–NS18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCloskey, J.C.; McCain, B.E. Satisfaction, Commitment and Professionalism of Newly Employed Nurses. Image–J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 1987, 19, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, M.F.; Thurston, N.E. Measuring Nurse Job Satisfaction. J. Nurs. Adm. 2004, 34, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegney, D.; Plank, A.; Parker, V. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Work Values: Their Impact on Job Satisfaction in Nursing. J. Nurs. Manag. 2006, 14, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.E. Job Satisfaction and Burnout among Foreign-Trained Nurses in Saudi Arabia: A Mixed-Method Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McGLYNN, K.; Griffin, M.Q.; Donahue, M.; Fitzpatrick, J.J. Registered Nurse Job Satisfaction and Satisfaction with the Professional Practice Model. J. Nurs. Manag. 2012, 20, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, L. Nurses’ Motivation and Its Relationship to the Characteristics of Nursing Care Delivery Systems: A Test of the Job Characteristics Model. Can. J. Nurs. Leadersh. 1999, 12, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gabr, H.; Mohamed, N. Job Characteristics Model to Redesign Nursing Care Delivery System in General Surgical Units. Acad. Res. Int. 2012, 2, 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, M.; Parker, V.; Mitchell, R.; Conway, J. How Do Nurse Consultant Job Characteristics Impact on Job Satisfaction? An Australian Quantitative Study. BMC Nurs. 2017, 16, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Othman, N.; Nasurdin, A.M. Job Characteristics and Staying Engaged in Work of Nurses: Empirical Evidence from Malaysia. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 6, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkul, G.; Karakul, A. The Relationship between Sleep Quality and Job Satisfaction of Nurses Working in the Pediatric Surgery Clinic during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Res. J. 2023, 9, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekonja, U.; Strnad, M.; Fekonja, Z. Association between Triage Nurses’ Job Satisfaction and Professional Capability: Results of a Mixed—Method Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 4364–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-F.; Lai, F.-C.; Huang, W.-R.; Huang, C.-I.; Hsieh, C.-J. Satisfaction With the Quality Nursing Work Environment Among Psychiatric Nurses Working in Acute Care General Hospitals. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 28, e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-S.; Yang, H.-H.; Chen, H.-T.; Chang, M.-F.; Chiu, Y.-F.; Chou, Y.-W.; Cheng, Y.-C. A Study of Nurses’ Job Satisfaction: The Relationship to Professional Commitment and Friendship Networks. Health 2012, 4, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Albougami, A.S.; Almazan, J.U.; Cruz, J.P.; Alquwez, N.; Alamri, M.S.; Adolfo, C.A.; Roque, M.Y. Factors Affecting Nurses’ Intention to Leave Their Current Jobs in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Health Sci. 2020, 14, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K.; Khan, S.A.; Al-Borie, H.M. Healthcare Human Resource Development in Saudi Arabia: Emerging Challenges and Opportunities—A Critical Review. Public Health Rev. 2019, 40, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Authority for Statistics Statistical Yearbook of 2017|Issue Number: 53. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/929-0 (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Almalki, M.; Fitzgerald, G.; Clark, M. Health Care System in Saudi Arabia: An Overview. East. Mediterr. Health J. Rev. Sante Mediterr. Orient. Al-Majallah Al-Sihhiyah Li-Sharq Al-Mutawassit 2011, 17, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzailai, N.; Barriball, L.; Xyrichis, A. Burnout and Job Satisfaction among Critical Care Nurses in Saudi Arabia and Their Contributing Factors: A Scoping Review. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 2331–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Clarke, S.P.; Sloane, D.M.; Sochalski, J.; Silber, J.H. Hospital Nurse Staffing and Patient Mortality, Nurse Burnout, and Job Dissatisfaction. JAMA 2002, 288, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; While, A.E.; Barriball, K.L. Job Satisfaction among Nurses: A Literature Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2005, 42, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falatah, R.; Salem, O.A. Nurse Turnover in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: An Integrative Review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Essential Public Health Functions, Health Systems and Health Security: Developing Conceptual Clarity and a WHO Roadmap for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-92-4-151408-8.

- The Healthy People. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Maqbali, M.A.A. Factors That Influence Nurses’ Job Satisfaction: A Literature Review. Nurs. Manag. 2015, 22, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhafeeri, Y.G.; Alenazi, M.F.; Alanazi, M.F.; Aldhafeeri, R.G.; Alzabni, K.A.; Aldhafeeri, A.D.; Aldhafeeri, A.M.; Aldhafeeri, M.G.; Alqasimi, J.S. Job Satisfaction Among Nurses in Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=Job+Satisfaction+Among+Nurses+in+Saudi+Arabia%3A+A+systematic+review&sca_esv=559545509 (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- AL-Dossary, R.; Vail, J.; Macfarlane, F. Job Satisfaction of Nurses in a Saudi Arabian University Teaching Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2012, 59, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamaideh, S.H. Burnout, Social Support, and Job Satisfaction among Jordanian Mental Health Nurses. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 32, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almujadidi, B.; Adams, A.; Alquaiz, A.; Van Gurp, G.; Schuster, T.; Andermann, A. Exploring Social Determinants of Health in a Saudi Arabian Primary Health Care Setting: The Need for a Multidisciplinary Approach. Int. J. Equity Health 2022, 21, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Reprint—Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddourah, B.; Abu-Shaheen, A.K.; Al-Tannir, M. Quality of Nursing Work Life and Turnover Intention among Nurses of Tertiary Care Hospitals in Riyadh: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMC Nurs. 2018, 17, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wali, R.; Aljohani, H.; Shakir, M.; Jaha, A.; Alhindi, H. Job Satisfaction Among Nurses Working in King Abdul Aziz Medical City Primary Health Care Centers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e33672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreshidi, N.M.; Alrashidi, L.M.; Alanazi, A.N.; Alshammeri, E.H. Turnover among Foreign Nurses in Saudi Arabia. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 10, jphr.2021.1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, M.; Alloubani, A.; Alzaatreh, M.; Abunab, H.; Gonzales, A.; Almatari, M. International Nursing: Job Satisfaction Among Critical Care Nurses in a Governmental Hospital in Saudi Arabia. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2018, 42, E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sabhan, T.F.; Ahmad, N.; Rasdi, I.; Mahmud, A. Job Satisfaction among Foreign Nurses in Saudi Arabia: The Contribution of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation Factors. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2022, 22, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haroon, H.I.; Al-Qahtani, M.F. The Demographic Predictors of Job Satisfaction among the Nurses of a Major Public Hospital in KSA. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2020, 15, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahnassy, A.; Alkaabba, A.; Saeed, A.; Ohaidib, T. Job Satisfaction of Nurses in a Tertiary Medical Care Center: A Cross Sectional Study, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Life Sci. J. 2014, 11, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi, A.G.A. Work Environment and Its Relationship with Job Satisfaction among Nurses in Riyadh Region, Saudi Arabia. Ph.D. Thesis, Majmaah University, Al Majma’ah, Saudi Arabia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Erarslan, A. The Role of Job Satisfaction in Predicting Teacher Emotions: A Study on English Language Teachers. Int. J. Contemp. Educ. Res. 2021, 8, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameddine, M.; Bauer, J.M.; Richter, M.; Sousa-Poza, A. The Paradox of Falling Job Satisfaction with Rising Job Stickiness in the German Nursing Workforce between 1990 and 2013. Hum. Resour. Health 2017, 15, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshmemri, M. Job Satisfaction of Saudi Nurses Working in Saudi Arabian Public Hospitals—RMIT University. Ph.D. Thesis, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aljohani, K. Nurses’ Job Satisfaction: A Multi-Center Study. Saudi J. Health Sci. 2019, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetterneck, T.B.; Linzer, M.; McMurray, J.E.; Douglas, J.; Schwartz, M.D.; Bigby, J.; Gerrity, M.S.; Pathman, D.E.; Karlson, D.; Rhodes, E.; et al. Worklife and Satisfaction of General Internists. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002, 162, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahmadi, H. Factors Affecting Performance of Hospital Nurses in Riyadh Region, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2009, 22, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapaksa, S.; Rothstein, W. Factors That Influence the Decisions of Men and Women Nurses to Leave Nursing. Nurs. Forum 2009, 44, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sochalski, J. Nursing Shortage Redux: Turning The Corner On An Enduring Problem. Health Aff. 2002, 21, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.-C.; Samuels, M.E.; Alexander, J.W. Factors That Influence Nurses’ Job Satisfaction. J. Nurs. Adm. 2003, 33, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacel, B.; Millar, M.; Norris, D. Measurement of Nurse Practitioner Job Satisfaction in a Midwestern State. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2005, 17, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aameri, A.S. Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment for Nurses. Saudi Med. J. 2000, 21, 531–535. [Google Scholar]

- Almalki, M.J.; FitzGerald, G.; Clark, M. The Relationship between Quality of Work Life and Turnover Intention of Primary Health Care Nurses in Saudi Arabia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahmadi, H.A. Job Satisfaction of Nurses in Ministry of Health Hospitals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2002, 23, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adams, A.; Bond, S. Hospital Nurses’ Job Satisfaction, Individual and Organizational Characteristics. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 32, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambur, B.; McIntosh, B.; Palumbo, M.V.; Reinier, K. Education as a Determinant of Career Retention and Job Satisfaction among Registered Nurses. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. Off. Publ. Sigma Theta Tau Int. Honor Soc. Nurs. 2005, 37, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, H.-M. The Influence of Nurses’ Working Motivation and Job Satisfaction on Intention to Quit: An Empirical Investigation in Taiwan. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2002, 39, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.-C.T.; Yang, K.-P.A. Nursing Turnover in Taiwan: A Meta-Analysis of Related Factors. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2002, 39, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, S.; Wilson, B.; Esterman, A. Perceptions of Working as a Nurse in an Acute Care Setting. J. Nurs. Manag. 2005, 13, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y. Turnover Propensity and Its Causes among Singapore Nurses: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2001, 12, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, H. Job Satisfaction Among Nurses in China. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2004, 17, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrabee, J.H.; Janney, M.A.; Ostrow, C.L.; Withrow, M.L.; Hobbs, G.R.; Burant, C. Predicting Registered Nurse Job Satisfaction and Intent to Leave. J. Nurs. Adm. 2003, 33, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.-C.; Lee, P.-H.; Yang, Y.-C.; Chang, W.-Y. Predicting Factors Related to Nurses’ Intention to Leave, Job Satisfaction, And Perception of Quality of Care In Acute Care Hospitals. Nurs. Econ. 2009, 27, 178–184, 202. [Google Scholar]

- Masum, A.K.M.; Azad, M.A.K.; Hoque, K.E.; Beh, L.-S.; Wanke, P.; Arslan, Ö. Job Satisfaction and Intention to Quit: An Empirical Analysis of Nurses in Turkey. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Top, M.; Gider, O. Interaction of Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction of Nurses and Medical Secretaries in Turkey. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 24, 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkelson, D.J.; Seed, M.S. Gender Differences in the Roles and Functions of Inpatient Psychiatric Nurses. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2011, 49, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, M.O. Workstress and Marital Relations; University of Cape Coast Institutional Repository: Cape Coast, Ghana, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Key Words | Databases Searched | Number of Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies that are of a quantitative type. | Systematic Review. | Saudi Nurses OR Staff Nurses OR Head Nurses OR Nurses Managers OR Undergraduate Nurses OR Postgraduate Nurses OR Saudi Nurse* AND Social Determinants of Health OR Cultural Issues OR Social Barriers OR Educational Barriers OR Environmental Factors OR Economical Factors OR Health Organization Challenges OR Determinants of Health OR SDOH* AND Job Satisfaction OR Work Satisfaction OR Workplace Satisfaction OR Satisfaction OR JS* | PubMed | 113 |

| Participants were Saudi and non-Saudi nurses. | Studies conducted outside Saudi Arabia | PsycINFO | 60 | |

| Studies settings should be at Saudi healthcare setting. | Studies that focus on other health profession. | CINAHL | 45 | |

| Studies written in English language. | Books. | Google Scholar | 17 | |

| Studies published in the last 11 years. | Unrelated language. | |||

| Total: 235 | ||||

| Studies published before 2012. |

| Checklist Questions | [42] | [36] | [39] | [20] | [41] | [38] | [43] | [40] | [37] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear (setting) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were confounding factors identified? | Unclear | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | Unclear | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hudays, A.; Gary, F.; Voss, J.G.; Zhang, A.Y.; Alghamdi, A. Utilizing the Social Determinants of Health Model to Explore Factors Affecting Nurses’ Job Satisfaction in Saudi Arabian Hospitals: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2394. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11172394

Hudays A, Gary F, Voss JG, Zhang AY, Alghamdi A. Utilizing the Social Determinants of Health Model to Explore Factors Affecting Nurses’ Job Satisfaction in Saudi Arabian Hospitals: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2023; 11(17):2394. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11172394

Chicago/Turabian StyleHudays, Ali, Fay Gary, Joachim G. Voss, Amy Y. Zhang, and Alya Alghamdi. 2023. "Utilizing the Social Determinants of Health Model to Explore Factors Affecting Nurses’ Job Satisfaction in Saudi Arabian Hospitals: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 11, no. 17: 2394. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11172394

APA StyleHudays, A., Gary, F., Voss, J. G., Zhang, A. Y., & Alghamdi, A. (2023). Utilizing the Social Determinants of Health Model to Explore Factors Affecting Nurses’ Job Satisfaction in Saudi Arabian Hospitals: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 11(17), 2394. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11172394