Faith-Based Spiritual Intervention for Persons with Depression: Preliminary Evidence from a Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aims

- To explore the acceptability and feasibility of a spiritual intervention for people with depression;

- To examine the effects of this intervention on depressive symptoms, hope, meaning in life, self-esteem and social support, anxiety levels, and daily spiritual experience;

- To explore the participants’ views on the healing mechanisms of the intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Ethical Considerations

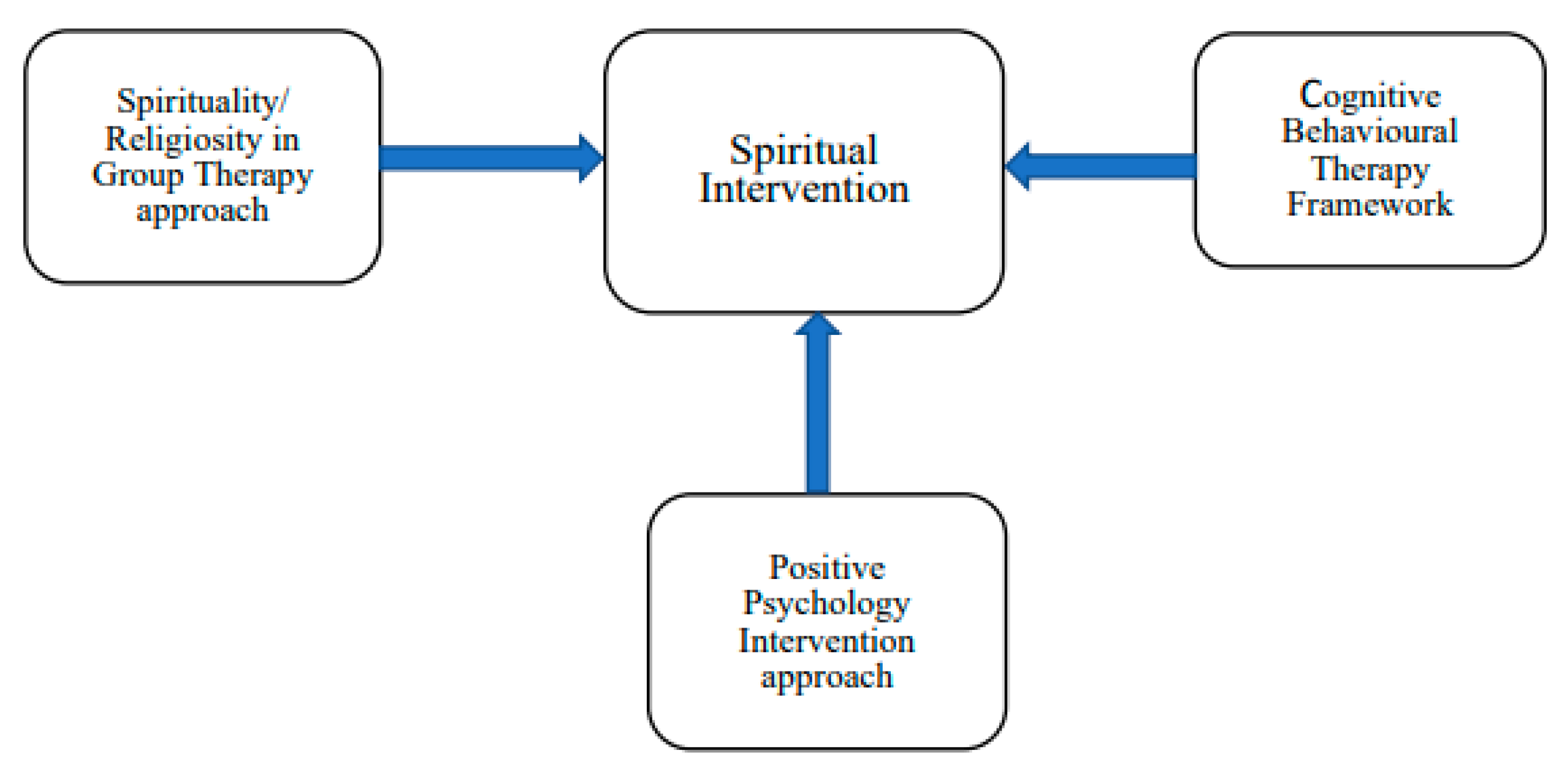

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Measurement

2.5.1. Acceptability and Feasibility

2.5.2. Measurement of the Outcomes

2.5.3. Focus Group

2.6. Treatment Fidelity

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

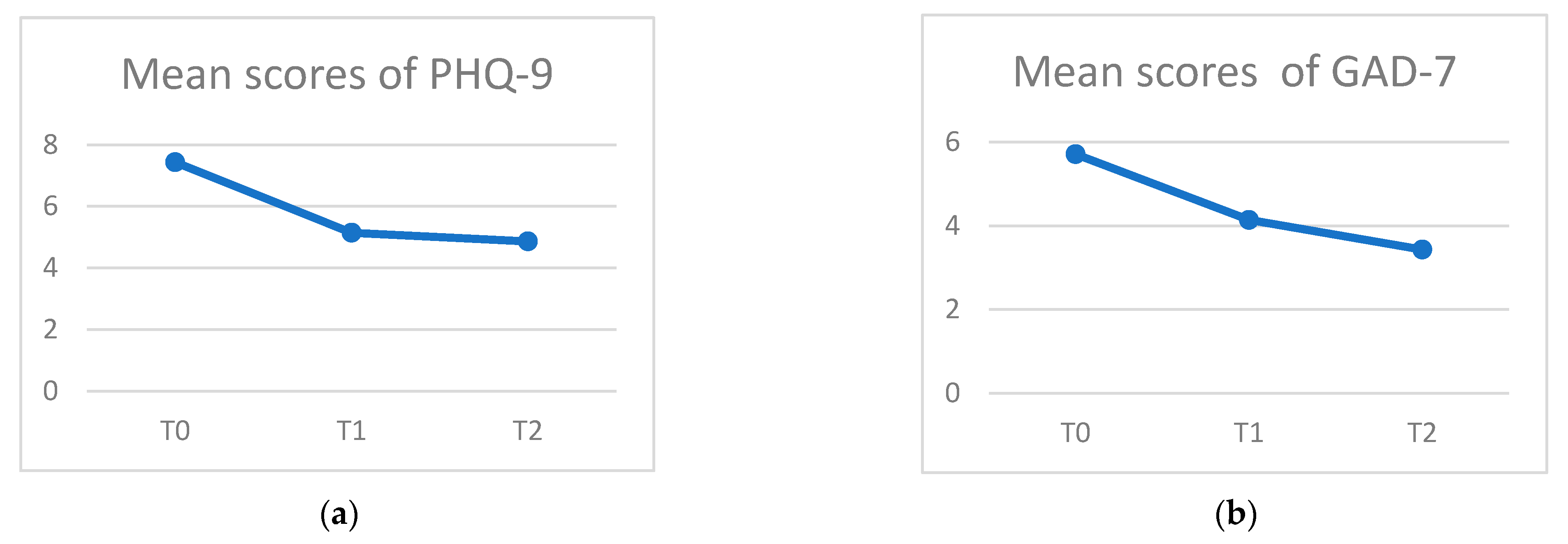

3.2. Quantitative Analysis

3.3. Qualitative Analysis

3.3.1. Meaning of the Spiritual Intervention

3.3.2. Effects of Involvement in the Spiritual Group

3.3.3. Therapeutic Factors/Components of the Spiritual Intervention

3.3.4. Participants’ Views on and Suggestions for the Program

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications and Suggestions for the Main Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Discussion Questions for the Focus Group

- When I say the word “spirituality” or “spiritual intervention”, what do you see or what do you think of?How would you describe the “spiritual intervention”?

- What do you think what kinds of factors will lead to the effectiveness of the spiritual intervention?

- What do you expect of a person who has participated in the spiritual intervention?

- What goes on in your spiritual intervention group?

- How do you see therapeutic processes involved in the spiritual intervention?

- Is there any other experience that you would like to share that we have not yet touched upon?

Appendix B. Checklist for Self-Monitoring of the Treatment Sessions

| Skills Competence of Interventionist | Always/ Almost Always | Sometimes | Missed Opportunity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Actively engages all participants in the discussion. | |||

| 2. Actively listens when a participant is talking. | |||

| 3. Communicates with all participants in a respectful, positive, and non-judgmental manner. | |||

| 4. Appropriately reinforces participants’ ideas and opinions. | |||

| 5. Correctly conveys/communicates the program’s principles. | |||

| 6. Communicates to participants that the participants are experts about their own problems. | |||

| 8. Facilitates sharing of ideas among the participants. | |||

| 9. Does not impose own ideas on the participants. | |||

| 10. Effectively responds when the participants are resistant to new strategies or ideas. | |||

| 11. Effectively manages challenging behavior from the participants in the group (e.g., monopolizing, anger, prolonged silence). | |||

| 12. Maintains a good pace for group discussions (not too fast, not too slow). | |||

| 13. Effectively uses role-play or group activities to teach a principle or strategy. | |||

| 14. Builds on the participants’ knowledge by incorporating the strategies discussed in previous sessions into this session. | |||

| 1 = skill rarely or never demonstrated (skill demonstrated < 25% of the time); 2 = skill sometimes/occasionally demonstrated (skill demonstrated 25–75% of the time); 3 = skill consistently demonstrated (skill demonstrated > 75% of the time); Modified from the Fidelity Checklist [68]. | |||

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Fact Sheet on Depression. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Bromet, E.J. The Epidemiology of Depression Across Cultures. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2013, 34, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Denson, L.A.; Dorstyn, D.S. Understanding Australian university students’ mental health help-seeking: An empirical and theoretical investigation. Aust. J. Psychol. 2018, 70, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno-Notivol, J.; Gracia-García, P.; Olaya, B.; Lasheras, I.; López-Antón, R.; Santabárbara, J. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: A meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2021, 21, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNSDG. Policy Brief: COVID-19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health. 13 May 2020. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-covid-19-and-need-action-mental-health (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Lake, J.; Turner, M.S. Urgent Need for Improved Mental Health Care and a More Collaborative Model of Care. Perm. J. 2017, 21, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiemke, C. Why Do Antidepressant Therapies Have Such a Poor Success Rate? Expert Rev. Neurother. 2016, 16, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, P.; Thomson, J.; Amstadter, A.; Neale, M.C. Primum non nocere: An evolutionary analysis of whether antidepressants do more harm than good. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirmaier, J.; Steinmann, M.; Krattenmacher, T.; Watzke, B.; Barghaan, D.; Koch, U.; Schulz, H. Non-Pharmacological Treatment of Depressive Disorders: A Review of Evidence-Based Treatment Options. Rev. Recent Clin. Trials 2012, 7, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Shan, W. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for major depressive disorder in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 281, 112595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, H.; Anheyer, D.; Cramer, H.; Dobos, G. Complementary therapies for clinical depression: An overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoz, Z.; Henderson, E.A. The World Religion Dataset, 1945–2010: Logic, Estimates, and Trends. Int. Interact. 2013, 39, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.M.; Grim, B.J. The World’s Religions in Figures: An Introduction to International Religious Demography; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 10–80. [Google Scholar]

- Brimblecombe, N.; Tingle, A.; Tunmore, R.; Murrells, T. Implementing holistic practices in mental health nursing: A national consultation. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomi, S.; Starnino, V.; Canda, E. Spiritual Assessment in Mental Health Recovery. Community Ment. Health J. 2014, 50, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallot, R.D. Spirituality and religion in psychiatric rehabilitation and recovery from mental illness. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2001, 13, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.B.; McCullough, M.E.; Poll, J. Religiousness and Depression: Evidence for a Main Effect and the Moderating Influence of Stressful Life Events. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 614–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, H.G.; McCullough, M.E.; Larson, D.B. Handbook of Religion and Health; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 1–228. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, H.G.M.D. Religion and Depression in Older Medical Inpatients. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2007, 15, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, L.E.; Peteet, J.R.; Cook, C.C.H. Spirituality and mental health. J. Study Spiritual. 2020, 10, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.S.; Berglund, P.A.; Kessler, R.C. Patterns and Correlates of Contacting Clergy for Mental Disorders in the United States. Health Serv. Res. 2003, 38, 647–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.; Wong, C.; Wang, M.-J.; Chan, W.-C.; Chen, E.; Ng, R.; Hung, S.-F.; Cheung, E.; Sham, P.-C.; Chiu, H.; et al. Prevalence, psychosocial correlates and service utilization of depressive and anxiety disorders in Hong Kong: The Hong Kong Mental Morbidity Survey (HKMMS). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, M.A.; Nagai-Jacobson, M.G. Spirituality: Living Our Connectedness; Delmar: Albany, NY, USA; Thomson Learning: Albany, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mattis, J.S. African American Women’s Definitions of Spirituality and Religiosity. J. Black Psychol. 2000, 26, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.B.; Stoll, R. Defining the Indefinable and Reviewing Its Place in Nursing. In Spiritual Dimension of Nursing Practice; Carson, V.B., Koenig, G.H., Eds.; Templeton Foundation Press: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, Z.W. Phenomenological Case Study of Spiritual Connectedness in the Academic Workplace. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2019, 9, 1156–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.-S. Relation Between Lack of Forgiveness and Depression: The Moderating Effect of Self-Compassion. Psychol. Rep. 2016, 119, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangel, T.; Webb, J.R. Forgiveness and substance use problems among college students: Psychache, depressive symptoms, and hopelessness as mediators. J. Subst. Use 2018, 23, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testerman, N. Forgiveness gives freedom. J. Christ. Nurs. A Q. Publ. Nurses Christ. Fellowsh. 2014, 31, 214. [Google Scholar]

- Egnew, T.R. The Meaning Of Healing: Transcending Suffering. Ann. Fam. Med. 2005, 3, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casellas-Grau, A.; Font, A.; Vives, J. Positive psychology interventions in breast cancer. A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology 2014, 23, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritschel, L.A.; Sheppard, C.S. Hope and depression. In The Oxford Handbook of Hope; Gallagher, M.W., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxfored University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 209–220. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, H.; Ebrahimi, L.; Vatandoust, L. Effectiveness of hope therapy protocol on depression and hope in amphetamine users. Int. J. High Risk Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, e21905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.-P. Spirituality, Connectedness, and Hope: The Higher Power Concept, Social Networks, and Inner Strengths. In Treating Addictions: The Four Components, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 209–244. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-C. Gratitude and depression in young adults: The mediating role of self-esteem and well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 87, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.; Steen, T.A.; Park, N.; Peterson, C.J. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulbure, B.T. Appreciating the Positive Protects us from Negative Emotions: The Relationship between gratitude, Depression and Religiosity. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 187, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feely, M.; Long, A. Depression: A psychiatric nursing theory of connectivity. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 16, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorajjakool, S.; Aja, V.; Chilson, B.; Ramírez-Johnson, J.; Earll, A. Disconnection, Depression, and Spirituality: A Study of the Role of Spirituality and Meaning in the Lives of Individuals with Severe Depression. Pastor. Psychol. 2008, 56, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaniol, L.; Bellingham, R.; Cohen, B.; Spaniol, S. The Recovery Workbook II: Connectedness. Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation; Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Boston University: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Warber, S.L.; Ingerman, S.; Moura, V.L.; Wunder, J.; Northrop, A.; Gillespie, B.W.; Durda, K.; Smith, K.; Rhodes, K.S.; Rubenfire, M. Healing the heart: A randomized pilot study of a spiritual retreat for depression in acute coronary syndrome patients. Explore J. Sci. Health 2011, 7, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Guetterman, T.C. Educational Researc: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 6th ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: London, UK, 2019; pp. 545–585. [Google Scholar]

- Sudak, D.M.; Codd, R.T.; Sludgate, J.; Sokol, L.; Fox, M.G.; Reiser, R.; Milne, D.L. Teaching and Supervising Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sin, N.L.; Lyubomirsky, S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 65, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalom, I.D. The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, 5th ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, L.G. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Overview and Results. Religions 2011, 2, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, L.G. Using the daily spiritual experience scale in research and practice. 2019, Preprint.

- Underwood, L.G.; Teresi, J.A. The daily spiritual experience scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Ann. Behav. Med. 2002, 24, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.-M.; Fong, T.C.T.; Tsui, E.Y.L.; Au-Yeung, F.S.W.; Law, S.K.W. Validation of the Chinese version of underwood’s daily spiritual experience scale-transcending cultural boundaries? Int. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 16, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Sympson, S.C.; Ybasco, F.C.; Borders, T.F.; Babyak, M.A.; Higgins, R.L. Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B.D.; Hirsch, J.K. State Hope Scale. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, W.W.S.; Ng, I.S.W.; Wong, C.C.Y. Resilience: Enhancing well-being through the positive cognitive triad. J. Couns. Psychol. 2011, 58, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Frazier, P.; Oishi, S.; Kaler, M. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the Presence of and Search for Meaning in Life. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.C.H. Factor Structure of the Chinese Version of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire among Hong Kong Chinese Caregivers. Health Soc. Work 2014, 39, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, S.-O.; Wong, P.-M. Validity and reliability of Chinese Rosenberg self-esteem scale. New Horiz. Educ. 2008, 56, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, D.P.; Allik, J. Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 53 nations: Exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wan, Q.; Huang, Z.; Huang, L.; Kong, F. Psychometric Properties of Multi-Dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in Chinese Parents of Children with Cerebral Palsy. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smarr, K.L.; Keefer, A.L. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63 (Suppl. S11), S454–S466. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lukai; Rongjing, D.; Dayi, H.; Sheng, L. GW25-e4488 The value of Chinese version GAD-7 and PHQ-9 to screen anxiety and depression in cardiovascular outpatients. JACC (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.) 2014, 64, C222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, M.C.; Baradley, M. Data Collection Methods: Semi-Structured Interviews and Focus Groups: Training Manual; RAND: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bellg, A.J.; Borrelli, B.; Resnick, B.; Hecht, J.; Minicucci, D.S.; Ory, M.; Ogedegbe, G.; Orwig, D.; Ernst, D.; Czajkowski, S. Enhancing Treatment Fidelity in Health Behavior Change Studies: Best Practices and Recommendations From the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychol. 2004, 23, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitenstein, S.M.; Fogg, L.; Garvey, C.; Hill, C.; Resnick, B.; Gross, D. Measuring Implementation Fidelity in a Community-Based Parenting Intervention. Nurs. Res. 2010, 59, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, R.M.; Simpson, P.M. Last Observation Carried Forward Versus Mixed Models in the Analysis of Psychiatric Clinical Trials. Am. J. Psychiatry 2009, 166, 639–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Pölkki, T.; Utriainen, K.; Kyngäs, H. Qualitative Content Analysis: A Focus on Trustworthiness. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korstjens, I.; Moser, A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thabane, L.; Ma, J.; Chu, R.; Cheng, J.; Ismaila, A.; Rios, L.P.; Robson, R.; Thabane, M.; Giangregorio, L.; Goldsmith, C.H. A tutorial on pilot studies: The what, why and how. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, J.; Arthur, D.G. Clients and facilitators’ experiences of participating in a Hong Kong self-help group for people recovering from mental illness. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2004, 13, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Spirituality, mental health, and depression |

| 2 | Connectedness |

| 3 | Forgiveness and freedom |

| 4 | Suffering and transcendence |

| 5 | Hope and gratitude |

| 6 | Relapse prevention, review of the materials, and celebration |

| Characteristics | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 46–55 | 3 | 42.9 |

| 56–64 | 4 | 57.1 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1 | 14.3 |

| Female | 6 | 85.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 3 | 42.9 |

| Married | 3 | 42.9 |

| Divorced | 1 | 14.3 |

| Religion | ||

| Protestant Christianity | 7 | 100 |

| Educational background | ||

| Secondary | 6 | 85.7 |

| Doctoral | 1 | 14.3 |

| Occupational status | ||

| Unemployed | 1 | 14.3 |

| Retired | 4 | 57.1 |

| Other | 2 | 28.6 |

| Received treatment | ||

| Yes | 7 | 100 |

| Assessment Outcome | Pre-Intervention (T0) Mean (SD) | Post-Intervention (T1) Mean (SD) | 3-Month Follow-Up (T2) Mean (SD) | p-Value | Cohen’s d T0 vs. T1 | Cohen’s d T0 vs. T2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 | 7.43 (3.409) | 5.14 (3.532) | 4.86 (4.598) | 0.094 * | −0.66 | −0.63 |

| GAD-7 | 5.71 (4.751) | 4.14 (3.436) | 3.43 (3.867) | 0.264 | −0.39 | −0.53 |

| DSES | 62.86 (21.075) | 65.57 (21.678) | 63.71 (20.131) | 0.580 | 0.13 | 0.04 |

| SHS | 30.29 (9.196) | 26.71 (11.309) | 29.43 (9.744) | 0.834 | −0.34 | −0.09 |

| MLQ-Presence | 26.14 (5.398) | 20.57 (9.071) | 22.86 (6.594) | 0.170 | −0.75 | −0.54 |

| MLQ-Search | 25.57 (10.277) | 20.29 (8.499) | 21.00 (7.937) | 0.568 | −0.56 | −0.49 |

| RSES | 30.00 (3.512) | 31.86 (5.956) | 32.14 (5.242) | 0.108 | 0.38 | 0.48 |

| MSPSS | 4.89 (1.103) | 4.42 (0.715) | 4.39 (0.938) | 0.607 | −0.51 | −0.49 |

| Words | Frequency |

|---|---|

| God | 86 |

| Prayer/pray | 31 |

| Bible | 18 |

| Support | 17 |

| Scripture | 17 |

| Sharing/share | 14 |

| Faith | 10 |

| Theme 1: Meaning of the Spiritual Intervention | |

|---|---|

| Category 1: Faith | |

| Category 2: Spiritual dimension | Subcategory 1: God’s almighty power |

| Subcategory 2: Spiritual guidance | |

| Subcategory 3: Spiritual inspiration | |

| Subcategory 4: Words of God | |

| Subcategory 5: Spiritual comfort | |

| Subcategory 6: Spiritual experience | |

| Subcategory 7: Prayer | |

| Category 2: Spiritual transformation | Subcategory 1: Spiritual growth |

| Subcategory 2: Centering | |

| Subcategory 3: Compassion | |

| Theme 2: Effect of the spiritual group | |

| Category 1: Group experience | Subcategory 1: Acceptance |

| Subcategory 2: Direction and focus | |

| Subcategory 3: Peer support | |

| Subcategory 4: Genuine sharing | |

| Subcategory 5: Better relationship with God | |

| Category 2: Increased understanding | Subcategory 1: Knowledge |

| Subcategory 2: Coping with depression | |

| Subcategory 3: Relapse prevention | |

| Subcategory 2: Gratitude | |

| Subcategory 3: Preparation in advance | |

| Category 4: Spiritual life | Subcategory 1: Communication with God |

| Subcategory 2: Devotion | |

| Category 5: Improvement of symptoms | Subcategory 1: Improvement in general condition |

| Subcategory 2: Coping | |

| Subcategory 3: Increased self-esteem | |

| Theme 3: Therapeutic factors/components of the spiritual intervention | |

| Category 1: Belief | Subcategory 1: Power of God |

| Subcategory 2: God’s omnipotence | |

| Subcategory 3: Relationship with God | |

| Subcategory 4: God is listening | |

| Category 2: Spiritual practice | Subcategory 1: Use of scripture |

| Subcategory 2: Prayer | |

| Subcategory 3: Sharing | |

| Subcategory 4: Testimonies | |

| Category 3: Group factors | Subcategory 1: Similar background |

| Subcategory 2: Emotional catharsis | |

| Subcategory 3: Support | |

| Category 4: Spiritual advancement | Subcategory 1: Forgiveness |

| Subcategory 2: Obedience | |

| Subcategory 3: Meaning in suffering | |

| Subcategory 4: Experiencing God | |

| Category 5: Inspiration | Subcategory 1: Self-understanding |

| Subcategory 2: Increased insight | |

| Theme 4: Participants’ views on and suggestions for the programme | |

| Category 1: Suggestions for the programme | Subcategory 1: Logistics of the program |

| Subcategory 2: Program’s content and duration | |

| Subcategory 3: Future suggestion | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leung, J.; Li, K.-K. Faith-Based Spiritual Intervention for Persons with Depression: Preliminary Evidence from a Pilot Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11152134

Leung J, Li K-K. Faith-Based Spiritual Intervention for Persons with Depression: Preliminary Evidence from a Pilot Study. Healthcare. 2023; 11(15):2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11152134

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeung, Judy, and Kin-Kit Li. 2023. "Faith-Based Spiritual Intervention for Persons with Depression: Preliminary Evidence from a Pilot Study" Healthcare 11, no. 15: 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11152134

APA StyleLeung, J., & Li, K.-K. (2023). Faith-Based Spiritual Intervention for Persons with Depression: Preliminary Evidence from a Pilot Study. Healthcare, 11(15), 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11152134