Relationships among Square Dance, Group Cohesion, Perceived Social Support, and Psychological Capital in 2721 Middle-Aged and Older Adults in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Square Dance and Group Cohesion

1.2. The Relationship between Perceived Social Support and Group Cohesion

1.3. The Relationship between Psychological Capital and Group Cohesion

1.4. The Serial Multiple Mediation Mechanism of Perceived Social Support and Psychological Capital

1.5. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

- Demographic information—Demographic information obtained in the questionnaire included participants’ sex, age, monthly income, BMI, intensity and duration of square dance exercise, and group size.

- Square dance exercise—Square dance exercise was assessed using the Physical Activity Rating Scale-3 (PARS-3) to examine individuals’ actual participation in square dance exercise in the last month [51]. In this study, Liang’s translation of the original PARS-3 was used [52]. The questionnaire contains three questions, one each on exercise intensity, duration, and frequency of activity. The calculation formula is: Amount of exercise = intensity × time × frequency, the scoring method is: intensity and frequency are scored from 1 to 5 points; time is scored from 0 to 4 points. The highest score is 100, and the lowest is 0. Regarding the evaluation criteria for the amount of exercise: <19 is categorized as low volume; 20–42 is categorized as medium volume; >43 is categorized as large volume. Cronbach’s α was 0.65, and the retest reliability of each item on the scale was 0.83.

- Perceived social support—Perceived social support was assessed using the Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS), which is used to examine individuals’ perceived social support from others [53]. In this study, the original PSSS was adjusted to Chinese by Jiang [54]. The questionnaire contains three dimensions with four items each: family support, friend support, and other support. The scale is scored on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). In this study, Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.95.

- Psychological capital—Psycap was assessed using the Positive Psychological Questionnaire (PPQ), which is used to examine individual psycap, i.e., the positive psychological states that people exhibit when they accomplish tasks and achievements [55]. In this study, the original PPQ was adjusted to Chinese by Zhang [56]. The questionnaire contains four dimensions with six dimensions each: self-efficacy, hope, optimism, and mental toughness. It is scored on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Items are averaged, with higher mean scores indicating a higher psycap. In this study, Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.91.

- Group cohesion—Group cohesion was assessed using the Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ), which is used to reflect the overall perception of the group and the degree of personal attraction of the members of a square dance organization in the pursuit of exercise goals [57]. In this study, the Chinese version of the GEQ translated and revised by Ma [58] was used to conduct the survey. The questionnaire contains four dimensions: interaction congruence, interaction attractiveness, task congruence, and task attractiveness. The scale has a total of 15 items and is scored on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). In this study, Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.90.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Results

3.2. Common Method Variance Test

3.3. Descriptive Statistics and Related Analysis

3.4. Differential Analysis

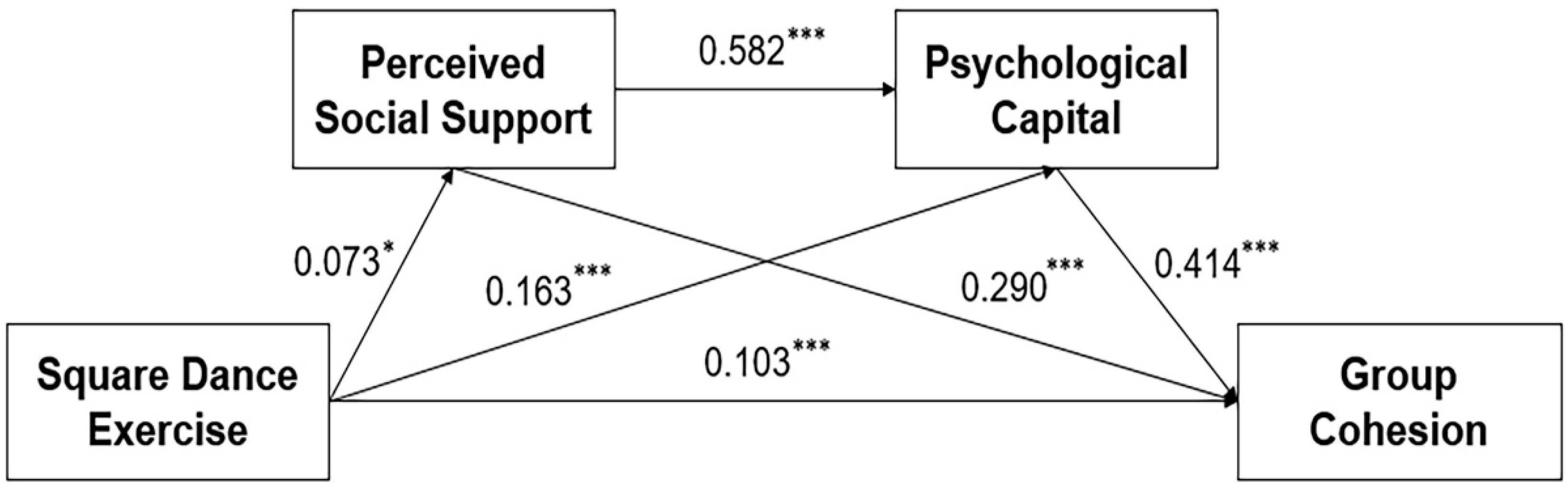

3.5. The Serial Mediating Effect of Perceived Social Support and Psychological Capital

4. Discussion

4.1. The Direct Relationship between Square Dance and Group Cohesion

4.2. The Intermediary Role of Perceived Social Support

4.3. The Intermediary Role of Psychological Capital

4.4. The Serial Multiple Mediation Mechanism of Perceived Social Support and Psychological Capital

4.5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

4.6. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, X.; Giles, J.; Yao, Y.; Yip, W.; Meng, Q.; Berkman, L.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Feng, J.; Feng, Z.; et al. The path to healthy aging in China: A Peking University-Lancet Commission. Lancet 2022, 400, 1967–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, E.L.; Matthews, C.E.; Freeman, J.R.; Gorzelitz, J.S.; Hong, H.G.; Liao, L.M.; McClain, K.M.; Saint-Maurice, P.F.; Shiroma, E.J.; Moore, S.C. Association of Leisure Time Physical Activity Types and Risks of All-Cause, Cardiovascular, and Cancer Mortality Among Older Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2228510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet 2018, 391, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, C.; Weng, L.J.; Botticello, A.L. Social participation reduces depressive symptoms among older adults: An 18-year longitudinal analysis in Taiwan. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubala, A.; MacGillivray, S.; Frost, H.; Kroll, T.; Skelton, D.A.; Gavine, A.; Gray, N.M.; Toma, M.; Morris, J. Promotion of physical activity interventions for community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review of reviews. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloza, J.; Castillo, B.; Micheo, W. Benefits of Exercise in the Older Population. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 28, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, D.E.; Kistner, T.M.; Richard, D.; Lee, I.M.; Baggish, A.L. The active grandparent hypothesis: Physical activity and the evolution of extended human healthspans and lifespans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2107621118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.Y.C.; Ou, K.L.; Chung, P.K.; Chui, K.Y.K.; Zhang, C.Q. The relationship between physical activity, physical health, and mental health among older Chinese adults: A scoping review. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 914548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.B. Square dance: Concept, function, and prospects. JB Dance Acad. 2018, 130, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yao, C.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Y. The beneficial effects of square dance on musculoskeletal system in early postmenopausal Chinese women: A cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.J.; Lin, Y.; Song, R. Leisure Satisfaction Mediates the Relationships between Leisure Settings, Subjective Well-Being, and Depression among Middle-Aged Adults in Urban China. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, 1001–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yin, M.; Li, Z. Acceptability and feasibility of public square dancing for community senior citizens with mild cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms: A pilot study. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2021, 8, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chater, N.; Zeitoun, H.; Melkonyan, T. The paradox of social interaction: Shared intentionality, we-reasoning, and virtual bargaining. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 129, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Hui, E.; Du, S.S.; Zhao, S.R.; Zhao, G.X. The Effect of Social Participation on The Attitudes to Aging of Rural Elderly: Mediating Effects of Self-Effificacy and Loneliness. J. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 45, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.; Silva, P.; Duarte, R.; Davids, K.; Garganta, J. Team Sports Performance Analysed Through the Lens of Social Network Theory: Implications for Research and Practice. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1689–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.P.M.A.; Queiroz, A.C.C.M.; Menezes, R.L.; Bachion, M.M. Effectiveness of senior dance in the health of adults and elderly people: An integrative literature review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2020, 41, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carron, A.V.; Brawley, L.R. Cohesion: Conceptual and measurement issues. Small Group Res. 2000, 31, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, D.R. Recent advances in the study of group cohesion. Group Dyn.-Theory Res. 2021, 25, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, B.T.; Schulz, A.J.; Mentz, G.; Israel, B.A.; Sand, S.L.; Reyes, A.G.; Hoston, B.; Richardson, D.; Gamboa, C.; Rowe, Z.; et al. Leader Behaviors, Group Cohesion, and Participation in a Walking Group Program. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M.T.; Nørregaard, L.B.; Jensen, T.D.; Frederiksen, A.S.; Ottesen, L.; Bangsbo, J. The effect of 5 years of team sport on elderly males’ health and social capital-An interdisciplinary follow-up study. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Armeli, S.; Rexwinkel, B.; Lynch, P.D.; Rhoades, L. Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadboukani, S.; Fathi, D.; Karami, M.; Bashirgonbadi, S.; Mahmoudpour, A.; Molaei, B. Providing a health-promotion behaviors model in elderly: Psychological capital, perceived social support, and attitudes toward death with mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation strategies. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 6, e1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shantz, A.; Kistruck, G.M.; Pacheco, D.F.; Webb, J.W. How formal and informal hierarchies shape conflict within cooperatives: A field experiment in Ghana. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 63, 503–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.L.; Jussila, I. Collective psychological ownership within the work and organizational context: Construct introduction and elaboration. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 810–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.C. Knowledge sharing and group cohesiveness on performance: An empirical study of technology r&d teams in taiwan. Technovation 2009, 29, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J.S.; Umberson, D.; Landis, K.R. Structures and processes of social support. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2003, 14, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, S. The relationships between social support and loneliness: A meta-analysis and review. Acta Psychol. 2022, 227, 103616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, K.S.; Bolger, N.; Higgins, E.T. Regulatory effectiveness of social support. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 119, 1316–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, H.; Yagasaki, K.; Saito, Y.; Oguma, Y. Regular group exercise contributes to balanced health in older adults in Japan: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley-Hague, H.; Horne, M.; Campbell, M.; Demack, S.; Skelton, D.A.; Todd, C. Multiple levels of influence on older adults’ attendance and adherence to community exercise classes. Gerontologist 2014, 54, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.J.; Wray, L.; Lin, Y. Social relationships, leisure activity, and health in older adults. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay Smith, G.; Banting, L.; Eime, R.; O’Sullivan, G.; van Uffelen, J.G.Z. The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. 2017, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moak, Z.B.; Agrawal, A. The association between perceived interpersonal social support and physical and mental health: Results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J. Public Health 2010, 32, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Li, W. The psychological capital of Chinese workers: Exploring the relationship with performance. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2005, 1, 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M. Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 4, 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Lynch, P.; Aselage, J.; Rohdieck, S. Who takes the most revenge? Individual differences in negative reciprocity norm endorsement. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management: Investing in people for competitive advantage. Organ. Dyn. 2004, 33, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ji, P.; Wang, Y.; Fan, H. The Association Between the Subjective Exercise Experience of Chinese Women Participating in Square Dance and Group Cohesion: The Mediating Effect of Income. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 700408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gully, S.M.; Incalcaterra, K.A.; Joshi, A.; Beauien, J.M. A meta-analysis of team-efficacy, potency, and performance: Interdependence and level of analysis as moderators of observed relationships. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Neveu, J.P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the Role of Resources in Conservation of Resources Theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibalija, J.; Savundranayagam, M.Y.; Orange, J.B.; Kloseck, M. Social support, social participation, & depression among caregivers and non-caregivers in Canada: A population health perspective. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Q. Mediating role of psychological capital in the relationship between social support and treatment burden among older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 1172–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarcheski, A.; Mahon, N.E. Meta-Analyses of Predictors of Hope in Adolescents. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2016, 38, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murawski, B.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Lubans, D.R.; Rayward, A.T.; Brown, W.J.; Vandelanotte, C.; Duncan, M.J. Examining mediators of intervention efficacy in a randomized controlled m-health trial to improve physical activity and sleep health in adults. Psychol. Health 2020, 35, 1346–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.I.; Cho, I.Y. Factors affecting parent health-promotion behavior in early childhood according to family cohesion: Focusing on the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 62, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahuas, A.; Marenus, M.W.; Kumaravel, V.; Murray, A.; Friedman, K.; Ottensoser, H.; Chen, W. Perceived social support and COVID-19 impact on quality of life in college students: An observational study. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, J.F.; Silveira, S.L.; Motl, R.W. Social cognitive theory variables are stronger correlates of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity than light physical activity in older adults with multiple sclerosis. Sport Sci. Health 2022, 18, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biazus-Sehn, L.F.; Schuch, F.B.; Firth, J.; Stigger, F.S. Effects of physical exercise on cognitive function of older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 89, 104048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, M.; Onishi, R.; Takashima, R.; Saeki, K.; Hirano, M. Effects of a social activity program that encourages interaction’ on rural older people’s psychosocial health: Mixed-methods research. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2023, 18, e12534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K. Stress, Exercise and Quality of Life; Paper Presented 1990; Beijing Asian Games Scientific Congress: Beijing, China, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D.Q. The stress level of college students and its relationship with physical exercise. Chin. Ment. Health J. 1994, 1, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, G.D.; Walker, R.R. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support: A confirmation study. J. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 52, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.J. The perceived social support scale. Chin. J. Behav. Med. Brain Sci. 2001, 10, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Competitive Edge; Oxford Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, S.; Dong, Y.H. Positive Psychological Capital Measurement and relationship with mental health. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2010, 8, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Carron, A.V.; Widmeyer, W.N.; Brawley, L.R. The development of an instrument to assess cohesion in sports teams: The Group Environment Questionnaire. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1985, 7, 244–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.Y. A revision Study on group Environment Questionnaire. JB Sports Univ. 2008, 3, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wen, Z.L. Item Parceling Strategies in Structural Equation Modeling. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 19, 1859–1867. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.L.; Hau, K.T.; Herbert, W.M. Structural equation model testing: Cutoff criteria for goodness of fit indices and chi-square test. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2004, 36, 186–194. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, R.; Teo, T. A tutorial on the meta-analytic structural equation modeling of reliability coefficients. Psychol. Methods 2020, 25, 747–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.B.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Tein, J.Y. Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.D.; Wen, Z.L. Statistical Approaches for Testing Common Method Bias: Problems and Suggestions. J. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 43, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Chen, L. Improving the Elderly-care Service System: Community Care Support and Health of the Elderly. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 49, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Reichard, R.J.; Luthans, F.; Mhatre, K.H. Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2011, 22, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Yan, H.; Sharma, M.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Li, P.; Ren, N.; Li, T.; Zhao, Y. Exploring factors influencing whether residents participate in square dancing using social cognitive theory: A cross-sectional survey in Chongqing, China. Medicine 2020, 99, e18685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakes, K.D.; Marvin, S.; Rowley, J.; San Nicolas, M.; Arastoo, S.; Viray, L.; Orozco, A.; Jurnak, F. Dancer perceptions of the cognitive, social, emotional, and physical benefits of modern styles of partnered dancing Complement. Ther. Med. 2016, 26, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraz, A.; Király, O.; Urbán, R.; Griffiths, M.D.; Demetrovics, Z. Why do you dance? Development of the Dance Motivation Inventory (DMI). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, S.; Wilke, N.; Ertl, K.; Fletcher, K.; Whittle, J. Group Cohesion in a Formal Exercise Program Composed of Predominantly Older Men. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2016, 42, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniehotta, F.F.; Gellert, P.; Witham, M.D.; Donnan, P.T.; Crombie, I.K.; McMurdo, M.E. Psychological theory in an interdisciplinary context: Psychological, demographic, health-related, social, and environmental correlates of physical activity in a representative cohort of community-dwelling older adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act 2013, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayotte, B.J.; Margrett, J.A.; Hicks-Patrick, J. Physical activity in middle-aged and young-old adults: The roles of self-efficacy, barriers, outcome expectancies, self-regulatory behaviors, and social support. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.M.; Young, J.A.; Harvey, J.T.; Charity, M.J.; Payne, W.R. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for adults: Informing the development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambegaonkar, J.P.; Matto, H.; Ihara, E.S.; Tompkins, C.; Caswell, S.V.; Cortes, N.; Davis, R.; Coogan, S.M.; Fauntroy, V.N.; Glass, E.; et al. Dance, Music, and Social Conversation Program Participation Positively Affects Physical and Mental Health in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Dance Med. Sci. 2022, 26, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latham, K.; Clarke, P.J. Neighborhood Disorder, Perceived Social Cohesion, and Social Participation Among Older Americans: Findings From the National Health & Aging Trends Study. J. Aging Health 2018, 30, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Xu, L.; Xu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Liao, B.; Li, Y.; Shi, Y. The relationship among pregnancy-related anxiety, perceived social support, family function and resilience in Chinese pregnant women: A structural equation modeling analysis. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.H.; Son, S.H.; Kang, S.H.; Kim, D.K.; Seo, K.M.; Lee, S.Y. Relationship between Types of Exercise and Quality of Life in a Korean Metabolic Syndrome Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2017, 15, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, M.; Park, J.H. The behavioral immune system (and why it matters). Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.; Cruwys, T.; Murray, K. Social support facilitates physical activity by reducing pain. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 576–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Teng, M.F.; Liu, S. Psychosocial profiles of university students’ emotional adjustment, perceived social support, self-efficacy belief, and foreign language anxiety during COVID-19. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2023, 40, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, E.; Bidstrup, B.; Mutch, A. Using information and communication technology learnings to alleviate social isolation for older people during periods of mandated isolation: A review. Australas. J. Ageing 2022, 41, e227–e239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Park, Y.S.; Allegrante, J.P.; Marks, R.; Ok, H.; Ok Cho, K.; Garber, C.E. Relationship between physical activity and general mental health. Prev. Med. 2012, 55, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E.M.; Rogers, R.G.; Wadsworth, T. Happiness and longevity in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 145, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlowski, T.; Downward, P.; Rasciute, S. Subjective well-being in European countries—On the age-specific impact of physical activity. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. A 2011, 8, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, B.R.; Zink, J.; Azad, A.; Campbell, C.E.; Chakravartti, S.P.; Herting, M.M. The Roles of Physical Activity, Exercise, and Fitness in Promoting Resilience during Adolescence: Effects on Mental Well-Being and Brain Development. Biol. Psychiatry-Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2021, 6, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, M.R.; Callaghan, P. The effect of exercise on resilience, its mediators and moderators, in a general population during the UK COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: A cross-sectional online study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, C.M.; Fred, L. Positivity in the Middle East: Developing Hope in Egyptian Organizational Leaders. Adv. Glob. Leadersh. 2006, 4, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Ji, B. Correlation Between Perceived Social Support and Loneliness Among Chinese Adolescents: Mediating Effects of Psychological Capital. Psychiatr. Danub. 2019, 31, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J.; De los Santos, J.A.A. COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: Predictive role of organizational support, personal resilience, and social support. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1653–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Sheng, Y. Social support network, social support, self-efficacy, health-promoting behavior and healthy aging among older adults: A pathway analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 85, 103934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, K.; Chen, X.; Wu, L. The effects of psychological capital on citizens’ willingness to participate in food safety social co-governance in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C. The Relationship between Parental Emotional Warmth and Rural Adolescents’ Hope The Sequential Mediating Role of Perceived Social Support and Prosocial Behavior. J. Genet. Psychol. 2023, 184, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cheung, T.; Xiang, Y.T. Mental health services for older adults in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, K.D.; Jacobs, H.I.L.; d’Oleire Uquillas, F.; Zide, B.S.; Kirn, D.R.; Properzi, M.R.; Rentz, D.M.; Johnson, K.A.; Sperling, R.A.; Donovan, N.J. Associations of Widowhood and β-Amyloid with Cognitive Decline in Cognitively Unimpaired Older Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e200121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wertz, J.; Caspi, A.; Ambler, A.; Broadbent, J.; Hancox, R.J.; Harrington, H.; Hogan, S.; Houts, R.M.; Leung, J.H.; Poulton, R.; et al. Association of History of Psychopathology With Accelerated Aging at Midlife. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Chang, J.; Liang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, D.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q.J.; Hu, H. Neural mechanism underlying depressive-like state associated with social status loss. Cell 2023, 186, 560–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, H.Y.; Cheng, P.P. A Study of Group Cohesion in Subjective Exercise Experience of Female Square Dance Participants in China from the Perspective of Healthy China. JB Sports Univ. 2022, 45, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total N = 2428 | Group Size < 25 N = 1279 (52.7%) | Group Size > 25 N = 1149 (47.3%) | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 60.62 ± 6.68 | 60.91 ± 6.79 | 60.31 ± 6.53 | 2.190 |

| Sex | ||||

| female | 2311 (95.2%) | 1231 (96.2%) | 1080 (94.0%) | |

| male | 117 (4.8%) | 48 (3.8%) | 69 (6.0%) | |

| BMI | 24.00 ± 48.75 | 22.97 ± 2.80 | 25.14 ± 70.81 | |

| Monthly income | ||||

| <3500 yuan | 1212 (49.9%) | 662 (51.8%) | 550 (47.9%) | |

| >3500 yuan | 1216 (50.1%) | 617 (48.2%) | 599 (32.1%) | |

| Square dance exercise intensity | 21.5 ± 14.43 | 19.47 ± 13.59 | 23.86 ± 14.97 | |

| Square dance exercise duration | ||||

| <5 years | 829 (34.1%) | 519 (40.6%) | 760 (59.4%) | |

| >5 years | 1599 (65.9%) | 310 (27.0%) | 839 (73.0%) | |

| PSSS | 69.32 ± 12.23 | 68.41 ± 12.65 | 70.39 ± 11.55 | −4.020 *** |

| PSSS-FS1 | 22.73 ± 4.53 | 22.42 ± 4.63 | 23.08 ± 4.35 | −3.581 *** |

| PSSS-FS2 | 23.82 ± 4.25 | 23.55 ± 4.40 | 24.14 ± 4.03 | −3.422 *** |

| PSSS-OS | 22.77 ± 4.50 | 22.43 ± 4.64 | 23.17 ± 4.28 | −4.071 *** |

| PPQ | 139.80 ± 19.78 | 137.58 ± 20.68 | 142.37 ± 18.09 | −6.036 *** |

| PPQ-SE | 39.24 ± 7.57 | 38.31 ± 7.92 | 40.31 ± 6.96 | −6.575 *** |

| PPQ-Resilience | 30.43 ± 6.34 | 30.23 ± 6.33 | 30.68 ± 6.28 | −1.782 |

| PPQ-Hope | 34.27 ± 5.83 | 33.65 ± 6.00 | 34.98 ± 5.48 | −5.677 *** |

| PPQ-Optimism | 35.85 ± 5.48 | 35.40 ± 5.72 | 36.39 ± 5.05 | −4.522 *** |

| GEQ | 88.78 ± 11.81 | 87.05 ± 12.72 | 90.71 ± 10.39 | −7.719 *** |

| ATG-S | 25.15 ± 3.54 | 24.69 ± 3.95 | 25.66 ± 2.93 | −6.841 *** |

| ATG-T | 18.90 ± 2.67 | 18.56 ± 2.96 | 19.28 ± 2.25 | −6.695 *** |

| GI-S | 20.23 ± 4.10 | 19.82 ± 4.01 | 20.69 ± 4.14 | −5.278 *** |

| GI-T | 24.50 ± 3.66 | 23.99 ± 3.96 | 25.08 ± 3.20 | −7.430 *** |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PARS-3 | 21.55 | 14.43 | _ | ||||||||||

| 2. PSSS-FS1 | 22.74 | 4.52 | 0.031 | _ | |||||||||

| 3. PSSS-FS2 | 23.84 | 4.24 | 0.080 ** | 0.707 ** | _ | ||||||||

| 4. PSSS-OS | 22.78 | 4.49 | 0.055 ** | 0.847 ** | 0.749 ** | _ | |||||||

| 5. PPQ-SE | 39.25 | 7.55 | 0.158 ** | 0.422 ** | 0.402 ** | 0.443 ** | _ | ||||||

| 6. PPQ-Resilience | 30.44 | 6.31 | −0.003 | 0.111 ** | 0.070 ** | 0.122 ** | 0.291 ** | _ | |||||

| 7. PPQ-Hope | 34.28 | 5.80 | 0.144 ** | 0.424 ** | 0.456 ** | 0.465 ** | 0.759 ** | 0.055 ** | _ | ||||

| 8. PPQ-Optimism | 35.87 | 5.44 | 0.115 ** | 0.499 ** | 0.511 ** | 0.535 ** | 0.740 ** | 0.235 ** | 0.798 ** | _ | |||

| 9. GEQ-ATG-S | 25.148 | 3.54 | 0.145 ** | 0.463 ** | 0.440 ** | 0.477 ** | 0.502 ** | 0.132 ** | 0.481 ** | 0.514 ** | _ | ||

| 10. GEQ-ATG-T | 18.90 | 2.67 | 0.156 ** | 0.430 ** | 0.430 ** | 0.450 ** | 0.507 ** | 0.116 ** | 0.498 ** | 0.518 ** | 0.916 ** | _ | |

| 11. GEQ-GI-S | 20.23 | 4.10 | 0.128 ** | 0.271 ** | 0.239 ** | 0.269 ** | 0.250 ** | −0.118 ** | 0.319 ** | 0.278 ** | 0.424 ** | 0.403 ** | _ |

| 12. GEQ-GI-T | 24.50 | 3.66 | 0.109 ** | 0.515 ** | 0.486 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.475 ** | 0.105 ** | 0.498 ** | 0.517 ** | 0.813 ** | 0.803 ** | 0.485 ** |

| Variables | Classification | Square Dance (M ± SD) | t | PSSS (M ± SD) | t | PPQ (M ± SD) | t | GEQ (M ± SD) | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | <60 | 21.93 ± 14.90 | −0.55 | 69.41 ± 12.32 | 0.30 | 140.33 ± 19.03 | 1.28 | 89.65 ± 11.76 | 3.86 *** |

| >60 | 21.15 ± 13.87 | 69.26 ± 12.17 | 139.31 ± 20.30 | 87.80 ± 11.79 | |||||

| Sex | Male | 27.53 ± 18.06 | 4.65 ** | 70.31 ± 11.76 | 0.88 | 140.03 ± 20.93 | 0.10 | 86.13 ± 13.68 | −2.48 ** |

| Female | 21.24 ± 14.15 | 69.30 ± 12.20 | 139.84 ± 19.58 | 88.91 ± 11.70 | |||||

| Monthly income (yuan) | <3500 | 21.33 ± 14.77 | −0.73 | 70.04 ± 12.54 | 2.81 ** | 140.48 ± 20.16 | 1.60 | 89.96 ± 11.32 | 4.94 *** |

| >3500 | 21.76 ± 14.07 | 68.66 ± 11.78 | 139.21 ± 19.10 | 87.60 ± 12.17 | |||||

| Marital status | Unmarried | 24.33 ± 16.52 | 0.67 | 69.92 ± 11.68 | 0.16 | 141.66 ± 11.56 | 0.32 | 89.25 ± 11.28 | 0.14 |

| Married | 21.53 ± 14.41 | 69.93 ± 12.19 | 139.84 ± 19.67 | 88.77 ± 11.81 |

| Intermediary Process | Effect Type | Effect Value | Bootstrapped LLCI a | Bootstrapped ULCI a | Effect Size (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Square dance—Perceived social support—Group cohesion | Mediating effect | 0.406 | 0.094 | 0.728 | 18.3 |

| Square dance—Psycap—Group cohesion | Mediating effect | 1.209 | 0.860 | 1.616 | 58.1 |

| Square dance—Perceived social support—Psycap—Group cohesion | Serial mediating effect | 0.209 | 0.054 | 0.402 | 8.4 |

| Mediating effect of PSSS | 0.669 | 0.456 | 0.944 | 10.1 | |

| Mediating effect of Psycap | 0.174 | 0.038 | 0.338 | 32.3 | |

| Total effect | 2.074 | 1.333 | 2.796 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chang, L.; Fan, H. Relationships among Square Dance, Group Cohesion, Perceived Social Support, and Psychological Capital in 2721 Middle-Aged and Older Adults in China. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2025. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11142025

Qu Y, Liu Z, Wang Y, Chang L, Fan H. Relationships among Square Dance, Group Cohesion, Perceived Social Support, and Psychological Capital in 2721 Middle-Aged and Older Adults in China. Healthcare. 2023; 11(14):2025. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11142025

Chicago/Turabian StyleQu, Yujia, Zhiyuan Liu, Yan Wang, Lei Chang, and Hongying Fan. 2023. "Relationships among Square Dance, Group Cohesion, Perceived Social Support, and Psychological Capital in 2721 Middle-Aged and Older Adults in China" Healthcare 11, no. 14: 2025. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11142025

APA StyleQu, Y., Liu, Z., Wang, Y., Chang, L., & Fan, H. (2023). Relationships among Square Dance, Group Cohesion, Perceived Social Support, and Psychological Capital in 2721 Middle-Aged and Older Adults in China. Healthcare, 11(14), 2025. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11142025