The Relationship between Nursing Practice Environment and Pressure Ulcer Care Quality in Portugal’s Long-Term Care Units

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Nursing Environment

2.1.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

2.1.2. Measurement Instrument

2.1.3. Data Collection

2.2. Wound Healing

2.2.1. Design

2.2.2. Measurement Instrument

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Nursing Environment

3.1.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.1.2. Work Environment

3.1.3. Suggestions for Improving Practice

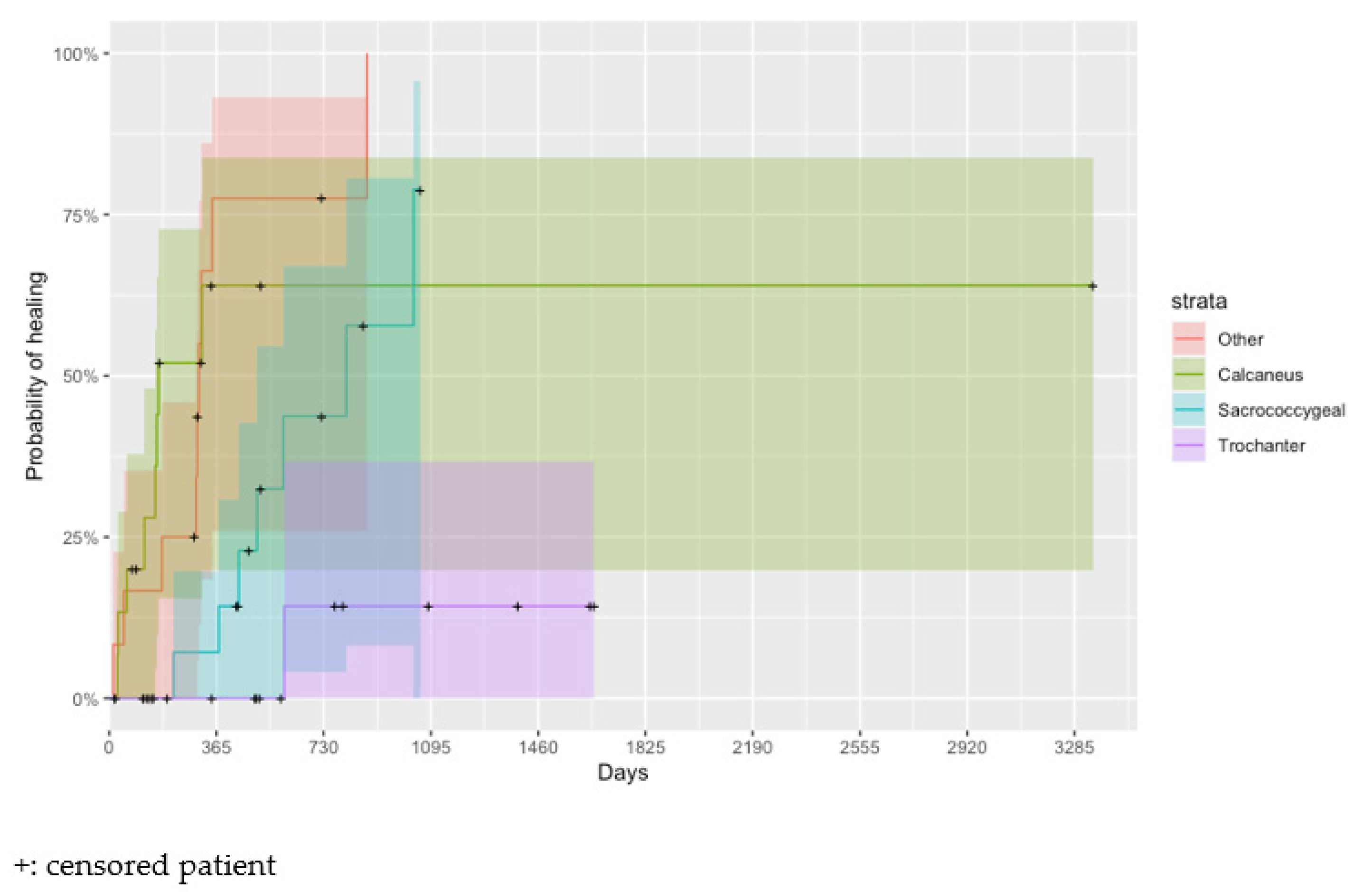

3.2. Wound Healing

3.3. Relationship between Work Environment and Wound Healing

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Quick Reference Guide. Haesler, E., Ed.; EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019; 62p, Available online: https://www.internationalguideline.com/static/pdfs/Quick_Reference_Guide-10Mar2019.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Mäki-Turja-Rostedt, S.; Stolt, M.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Haavisto, E. Preventive interventions for pressure ulcers in long-term older people care facilities: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 28, 2420–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poldrugovac, M.; Padget, M.; Schoonhoven, L.; Thompson, N.D.; Klazinga, N.S.; Kringos, D.S. International comparison of pressure ulcer measures in long-term care facilities: Assessing the methodological robustness of 4 approaches to point prevalence measurement. J. Tissue Viability 2021, 30, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sving, E.; Fredriksson, L.; Mamhidir, A.-G.; Hogman, M.; Gunningberg, L. A multifaceted intervention for evidence-based pressure ulcer prevention: A 3 year follow-up. JBI Evid. Implement. 2020, 18, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitty, J.A.; McInnes, E.; Bucknall, T.; Webster, J.; Gillespie, B.M.; Banks, M.; Thalib, L.; Wallis, M.; Cumsille, J.; Roberts, S.; et al. The cost-effectiveness of a patient centred pressure ulcer prevention care bundle: Findings from the INTACT cluster randomised trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 75, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shi, C.; Dumville, J.C.; Cullum, N. Evaluating the development and validation of empirically-derived prognostic models for pressure ulcer risk assessment: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 89, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stern, A.; Chen, W.; Sander, B.; John-Baptiste, A.; Thein, H.H.; Gomes, T.; Wodchis, W.P.; Bayoumi, A.; Machado, M.; Carcone, S.; et al. Preventing pressure ulcers in long-term care: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011, 171, 1839–1847. [Google Scholar]

- Kuffler, D.P. Improving the ability to eliminate wounds and pressure ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2015, 23, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodall, R.; Armstrong, A.; Hughes, W.; Fries, C.A.; Marshall, D.; Harbinson, E.B.; Salciccioli, J.; Shalhoub, J. Trends in Decubitus Ulcer Disease Burden in European Union 15+ Countries, from 1990 to 2017. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2020, 8, e3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyder, C. The Benefits of a Multi-Disciplinary Approach to the Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers. 2011. Available online: https://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/infections/benefits-multi-disciplinary-approach-prevention-and-treatment-pressure-ulcers (accessed on 24 January 2017).

- Mallah, Z.; Nassar, N.; Badr, L.K. The Effectiveness of a Pressure Ulcer Intervention Program on the Prevalence of Hospital Acquired Pressure Ulcers: Controlled Before and After Study. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2015, 28, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Z.; Cowma, S. Quality of Life and Pressure Ulcers: A literature review. Wounds UK 2009, 5, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, C. Vidas Partidas—Enfermeiros Portugueses no Estrangeiro; Lusodidacta: Lisboa, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Coyer, F.; Cook, J.-L.; Doubrovsky, A.; Campbell, J.; Vann, A.; McNamara, G. Understanding contextual barriers and enablers to pressure injury prevention practice in an Australian intensive care unit: An exploratory study. Aust. Crit. Care 2019, 32, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Wu, Z.; Song, B.; Coyer, F.; Chaboyer, W. The effectiveness of multicomponent pressure injury prevention programs in adult intensive care patients: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 102, 103483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACSS-DRS. Relatório de Monitorização da Rede Nacional de Cuidados Continuados Integrados (RNCCI). 2020, pp. 2–52. Available online: https://www.acss.min-saude.pt/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Relatorio-de-Monitorizac%CC%A7a%CC%83o-da-RNCCI- (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- ACSS-DRS. Relatorio de Monitorização da Rede Nacional de Cuidados Continuados Integrados. 2021, pp. 1–201. Available online: https://www.acss.min-saude.pt/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Relatorio-de-Monitorizac%CC%A7a%CC%83o-da-RNCCI- (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Arisandi, D.; Ogai, K.; Urai, T.; Aoki, M.; Minematsu, T.; Okamoto, S.; Sanada, H.; Nakatani, T.; Sugama, J. Development of recurrent pressure ulcers, risk factors in older patients: A prospective observational study. J. Wound Care 2020, 29, S14–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieper, B. Pressure Ulcers: Impact, Etiology, and Classification. Wound Manag. 2015, pp. 124–139. Available online: https://www.chirocredit.com/downloads/woundmanagement/woundmanagement110.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Furtado, K.; Infante, P.; Sobral, A.; Gaspar, P.; Eliseu, G.; Lopes, M. Prevalence of acute and chronic wounds—With emphasis on pressure ulcers—In integrated continuing care units in Alentejo, Portugal. Int. Wound J. 2020, 17, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2019; Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos: Paris, France, 2019; pp. 2–4. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance_19991312 (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Alshahrani, B.; Sim, J.; Middleton, R. Nursing interventions for pressure injury prevention among critically ill patients: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 2151–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtado, K.; Lopes, T.; Afonso, A.; Infante, P.; Voorham, J.; Lopes, M. Content Validity and Reliability of the Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test and the Knowledge Level of Portuguese Nurses at Long-Term Care Units: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slater, P.; McCormack, B. An Exploration of the Factor Structure of the Nursing Work Index. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2007, 4, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, A.M.; Ball, J.; Aiken, L.H. Are teamwork and professional autonomy compatible, and do they result in improved hospital care? Qual. Health Care 2001, 10 (Suppl. 2), 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.M.; Bruyneel, L.; Van den Heede, K.; Griffiths, P.; Busse, R.; Diomidous, M.; Kinnunen, J.; Kózka, M.; Lesaffre, E.; et al. Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: A retrospective observational study. Lancet 2014, 383, 1824–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lucas, P.; Jesus, E.; Almeida, S.; Araújo, B. Validation of the Psychometric Properties of the Practice Environment Scale of Nursing Work Index in Primary Health Care in Portugal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assembleia da República. Lei no 21/2014, de 16 de Abril—Aprova a Lei da Investigação Clínica. In Diário da República; 1A Série—No. 75; National Printing House: Lisbon, Portugal, 2014; pp. 2450–2465. Available online: https://dre.pt/application/dir/pdf1sdip/2014/04/07500/0245002465.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.M.; Clarke, S.; Poghosyan, L.; Cho, E.; You, L.; Finlayson, M.; Kanai-Pak, M.; Aungsuroch, Y. Importance of work environments on hospital outcomes in nine countries. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2011, 23, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aiken, L.H.; Cerón, C.; Simonetti, M.; Lake, E.T.; Galiano, A.; Garbarini, A.; Soto, P.; Bravo, D.; Smith, H.L. Hospital nurse staffing and patient outcomes. Rev. Médica Clínica Condes 2018, 29, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigan, G.H.; Guirardello, E. Nursing practice environment, satisfaction and safety climate: The nurses’ perception. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2017, 30, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Bogaert, P.; Clarke, S.; Vermeyen, K.; Meulemans, H.; Van de Heyning, P. Practice environments and their associations with nurse-reported outcomes in Belgian hospitals: Development and preliminary validation of a Dutch adaptation of the Revised Nursing Work Index. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Bogaert, P.; Timmermans, O.; Weeks, S.M.; van Heusden, D.; Wouters, K.; Franck, E. Nursing unit teams matter: Impact of unit-level nurse practice environment, nurse work characteristics, and burnout on nurse reported job outcomes, and quality of care, and patient adverse events—A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mutair, A.; Al Mutairi, A.; Schwebius, D. The retention effect of staff education programme: Sustaining a decrease in hospital-acquired pressure ulcers via culture of care integration. Int. Wound J. 2021, 18, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai-Pak, M.; Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.M.; Poghosyan, L. Poor work environments and nurse inexperience are associated with burnout, job dissatisfaction and quality deficits in Japanese hospitals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 3324–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akhu-Zaheya, L.; Al-Maaitah, R.; Hani, S.B. Quality of nursing documentation: Paper-based health records versus electronic-based health records. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 27, e578–e589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihdawi, M.; Al-Amer, R.; Darwish, R.; Randall, S.; Afaneh, T. The Influence of Nursing Work Environment on Patient Safety. Work. Health Saf. 2020, 68, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temkin-Greener, H.; Cai, S.; Zheng, N.T.; Zhao, H.; Mukamel, D.B. Nursing Home Work Environment and the Risk of Pressure Ulcers and Incontinence. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 47, 1179–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, A.; Bradywood, A.; Williams, B.; Blackmore, C.C. Association of Use of Contract Nurses with Hospitalized Patient Pressure Injuries and Falls. J. Nurs. Sch. 2020, 52, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: Following considerable dveelopment in the field since 2006, MRC and NIHR have jointly commisioned and update of this guidance to be published in 2019. BMJ 2019, 50, 587–592. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Yu, H.; Liang, N.; Zhu, S.; Li, X.; Robinson, N.; Liu, J. Components of complex interventions for healthcare: A narrative synthesis of qualitative studies. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. Sci. 2020, 7, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anunciada, S.; Benito, P.; Gaspar, F.; Lucas, P. Validation of Psychometric Properties of the Nursing Work Index—Revised Scale in Portugal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério da Saúde. Decreto-Lei no 101/2006 Rede Nacional de Cuidados Continuados Integrados. In Diário da República; I série-A no109 6 Junho 2006; National Printing House: Lisbon, Portugal, 2006; pp. 3856–3865. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Saúde. Decreto de Lei 136/2015 de 28 de julho. In Diário da República; National Printing House: Lisbon, Portugal, 2015; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M.; Hafner, L.P. Shared values: Impact on Staff Nurse Job Satisfaction And Perceieved Productivity. Nurs. Res. 1989, 38, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.H.; Patrician, P.A. Measuring Organizational Traits of Hospitals: The Revised Nursing Work Index. Nurs. Res. 2000, 49, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-F.; Lake, E.T.; Sales, A.; Sharp, N.D.; Greiner, G.T.; Lowy, E.; Liu, C.-F.; Mitchell, P.H.; Sochalski, J.A. Measuring nurses’ practice environments with the revised nursing work index: Evidence from registered nurses in the veterans health administration. Res. Nurs. Health 2007, 30, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, H.S.; Guirardello, E.d.B. Nursing work environment and accreditation: Is there a relationship? J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 2183–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, E.T. Development of the practice environment scale of the nursing work index. Res. Nurs. Health 2002, 25, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.; Miguéns, C.; Gouveia, J.; Furtado, K. Medição da qualidade de vida de doentes com feridas crónicas: A Escala de Cicatrização da Úlcera de Pressão e o Esquema de Cardiff de Impacto da Ferida. Rev. Nurs. 2007, 221, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Stotts, N.A.; Rodeheaver, G.T.; Thomas, D.R.; Frantz, R.A.; Bartolucci, A.A.; Sussman, C.; Ferrell, B.A.; Cuddigan, J.; Maklebust, J. An Instrument to Measure Healing in Pressure Ulcers: Development and Validation of the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH). J. Gerontol. Ser. A Boil. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M795–M799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP). PUSH Tool Information; NPUAP: Rockville, MD, USA, 1997; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.; Bates-Jensen, B.; Parslow, N.; Raizman, R.; Singh, M.; Ketchen, R. Bates-jensen wound assessment tool: Pictorial guide validation project. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2010, 37, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates-Jensen, B.M.; McCreath, H.E.; Harputlu, D.; Patlan, A. Reliability of the Bates-Jensen wound assessment tool for pressure injury assessment: The pressure ulcer detection study. Wound Repair Regen. 2019, 27, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restrepo-Medrano, J.C.; Soriano, J.V. Development of a wound healing index for chronic wounds. Gerokomos 2011, 22, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berlowitz, D.R.; Ratliff, C.; Cuddigan, J.; Rodeheaver, G.T. The PUSH tool: A survey to determine its perceived usefulness. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2005, 18, 480–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günes, U.Y. A prospective study evaluating the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH Tool) to assess stage II, stage III, and stage IV pressure ulcers. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2009, 55, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Simes, R. An improved Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika 1986, 73, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Cimiotti, J.P.; Sloane, D.M.; Smith, H.L.; Flynn, L.; Neff, D.F. Effects of Nurse Staffing and Nurse Education on Patient Deaths in Hospitals with Different Nurse Work Environments. Med. Care 2011, 49, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Warren, J.I.; McLaughlin, M.; Bardsley, J.; Eich, J.; Esche, C.A.; Kropkowski, L.; Risch, S. The Strengths and Challenges of Implementing EBP in Healthcare Systems. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2016, 13, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, A.; Grant, M.J.; Carroll, D.; Dalton, S.; Deaton, C.; Jones, I.; Lehwaldt, D.; McKee, G.; Munyombwe, T.; Astin, F. The effect of nurse-to-patient ratios on nurse-sensitive patient outcomes in acute specialist units: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2018, 17, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Munroe, D.J. The influence of registered nurse staffing on the quality of nursing home care. Res. Nurs. Health 1990, 13, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshodi, T.O.; Bruneau, B.; Crockett, R.; Kinchington, F.; Nayar, S.; West, E. The nursing work environment and quality of care: Content analysis of comments made by registered nurses responding to the Essentials of Magnetism II scale. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sherman, R.O. Fostering the Power of Connection. Nurse Lead. 2022, 20, 326–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, P.R.; Clarkson, P.; Bader, D.L.; Schoonhoven, L. Identifying barriers and facilitators to participation in pressure ulcer prevention in allied healthcare professionals: A mixed methods evaluation. Physiotherapy 2016, 103, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgado, B.; Fonseca, C.; Lopes, M.; Pinho, L. Components of Care Models that Influence Functionality in People Over 65 in the Context of Long-Term Care: Integrative Literature Review. In Gerontechnology III. IWoG 2020; Lecture Notes in Bioengineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.; Griffiths, P.; Rafferty, A.M.; Bruyneel, L.; McHugh, M.; Maier, C.B.; Moreno-Casbas, T.; Ball, J.E.; Ausserhofer, D.; et al. Nursing skill mix in European hospitals: Cross-sectional study of the association with mortality, patient ratings, and quality of care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2016, 26, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Horn, S.D.; Bender, S.A.; Ferguson, M.L.; Smout, R.J.; Rn, N.B.; Taler, G.; Cook, A.S.; Mba, S.S.S.; Voss, A.C. The National Pressure Ulcer Long-Term Care Study: Pressure Ulcer Development in Long-Term Care Residents. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsdóttir, S.; Clarke, S.P.; Rafferty, A.M.; Nutbeam, D. Front-line management, staffing and nurse-doctor relationships as predictors of nurse and patient outcomes. A survey of Icelandic hospital nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Park, S.H. Hospital Magnet Status, Unit Work Environment, and Pressure Ulcers. J. Nurs. Sch. 2015, 47, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunningberg, L.; Fogelberg-Dahm, M.; Ehrenberg, A. Improved quality and comprehensiveness in nursing documentation of pressure ulcers after implementing an electronic health record in hospital care. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 1557–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, S.; Hudak, S.; Horn, S.D.; Barrett, R.; Spector, W.; Limcangco, R. Exploratory Study of Nursing Home Factors Associated with Successful Implementation of Clinical Decision Support Tools for Pressure Ulcer Prevention. Adv. Ski. Wound Care 2013, 26, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubaishat, A.; Tawalbeh, L.I.; AlAzzam, M.; AlBashtawy, M.; Batiha, A.-M. Electronic versus paper records: Documentation of pressure ulcer data. Br. J. Nurs. 2015, 24, S30–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnunen, U.M.; Saranto, K.; Ensio, A.; Iivanainen, A.; Dykes, P. Developing the standardized wound care documentation model: A delphi study to improve the quality of patient care documentation. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2012, 39, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R.-L.; Fossum, M. Nursing documentation of pressure ulcers in nursing homes: Comparison of record content and patient examinations. Nurs. Open 2016, 3, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gunningberg, L.; Lindholm, C.; Carlsson, M.; Sjoden, P.-O. Risk, prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers—Nursing staff knowledge and documentation. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2001, 15, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeMaster, K.M. Reducing Incidence and Prevalence of Hospital-Acquired Pressure Ulcers at Genesis Medical Center. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2007, 33, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moda Vitoriano Budri, A.; Moore, Z.; Patton, D.; O’Connor, T.; Nugent, L.; Mc Cann, A.; Avsar, P. Impaired mobility and pressure ulcer development in older adults: Excess movement and too little movement—Two sides of the one coin? J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2927–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, M.; Unosson, M.; Fredrikson, M.; Ek, A.C. Immobility—A major risk factor for development of pressure ulcers among adult hospitalized patients: A prospective study. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2004, 18, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaul, E.; Barron, J.; Rosenzweig, J.P.; Menczel, J. An overview of co-morbidities and the development of pressure ulcers among older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, K.-L.; Chen, L.; Kang, Y.-Y.; Xing, L.-N.; Li, H.-L.; Cheng, P.; Song, Z.-H. Identification of risk factors of developing pressure injuries among immobile patient, and a risk prediction model establishment. Medicine 2020, 99, e23640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljezawi, M.; Al Qadire, M.; Tubaishat, A. Pressure ulcers in long-term care: A point prevalence study in Jordan. Br. J. Nurs. 2014, 23 (Suppl. 6), S4–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, D.; Alosoumi, D.; Safari, R. Prevalence of pressure ulcers in long-term care: A global review. J. Wound Care 2019, 28, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courvoisier, D.S.; Righi, L.; Béné, N.; Rae, A.-C.; Chopard, P. Variation in pressure ulcer prevalence and prevention in nursing homes: A multicenter study. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 42, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Item | Cronbach’s Alpha | Component | Item | Cronbach’s Alpha | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management support | 2 | 0.75 | 0.86 | Collegial Nurse-Physician relations | 1 | 0.63 | 0.77 |

| 6 | 0.5 | 15 | 0.7 | ||||

| 7 | 0.63 | 20 | 0.74 | ||||

| 9 | 0.74 | 24 | 0.92 | ||||

| 10 | 0.66 | Endowments | 8 | 0.81 | 0.65 | ||

| 13 | 0.68 | 12 | 0.9 | ||||

| 18 | 0.7 | 28 | 0.26 | ||||

| 23 | 0.65 | Organisation of nursing care | 11 | 0.67 | 0.59 | ||

| Professional development | 3 | 0.45 | 0.81 | 14 | 0.37 | ||

| 4 | 0.7 | 25 | 0.35 | ||||

| 5 | 0.7 | 26 | 0.63 | ||||

| 16 | 0.71 | ||||||

| 17 | 0.63 | ||||||

| 19 | 0.62 | ||||||

| Fundamentals of nursing | 21 | 0.57 | 0.69 | ||||

| 22 | 0.55 | ||||||

| 27 | 0.54 | ||||||

| 29 | 0.39 | ||||||

| 30 | 0.6 | ||||||

| 31 | 0.55 | ||||||

| Long-Term Care Unit Type | Population | Sample Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| ULDM (long stay) | 206 | 31 (15.0) |

| UMDR (medium stay and rehabilitation) | 122 | 69 (56.6) |

| UC (short stay and complex cases) | 102 | 38 (37.3) |

| UCP (palliative care) | 21 | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 451 | 138 (30.6) |

| Variable | Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 103 (74.6) |

| Male | 35 (25.4) | |

| Education | Graduate | 128 (92.7) |

| Master | 10 (7.3) | |

| Education in Wound Care | No | 85 (61.6) |

| Yes | 53 (38.4) | |

| Type of wound training | Short-term course | 34 (64.2) |

| Postgraduation | 19 (35.8) | |

| Professional Experience | <1 year | 26 (18.8) |

| 1–5 years | 46 (33.3) | |

| 6–10 years | 34 (24.6) | |

| 11–20 years | 17 (12.3) | |

| >20 years | 15 (11.0) | |

| Professional Experience in the organisation | <1 year | 38 (27.5) |

| 1–5 years | 60 (43.5) | |

| 6–10 years | 25 (18.1) | |

| 11–20 years | 15 (10.9) | |

| Other employment | No | 88 (63.8) |

| Yes | 50 (36.2) |

| Unit | n Nurses | Hours Worked | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Range | ||

| ULDM | 109 | 80 (48–140) | 8–190 |

| UC | 35 | 120 (72–148) | 8–192 |

| UMDR | 63 | 76 (46–140) | 8–192 |

| UCP | 5 | 40 (12–140) | 12–192 |

| Education in Wound Care (Q17) | No opportunities to attend course. |

| No nurses with knowledge, competence, and experience (lots of young nurses) | |

| Units Capacity (Q12), (Q28) | Need an adequate nurse/patient ratio and to reduce workload. |

| Inadequate labour conditions for the real needs of patients (few nurses, constrains in the equipment) | |

| Conflicts between financial income and fair salaries (Q3) (Q28) | The salary in long-term care units is lower than in the NHS |

| Need more flexibility in schedules and holidays. | |

| Nurse–Physician relationship (Q5) | No support from physicians. |

| Nurses are excluded from decision-making in issues related with patients. | |

| Structural and political changes are necessary in long-term care units (Q5) | Political and organisational changes are needed. |

| Improvements in monthly documentation in GESTCare® platform (Q5) | The electronic record system needs an update. |

| Question Number | Description |

|---|---|

| Q3 | A satisfactory salary. |

| Q5 | Opportunity for staff nurses to participate in policy decisions. |

| Q12 | Enough staff to get the work done. |

| Q17 | Nursing staff is supported in pursuing degrees in nursing. |

| Q28 | Floating, so that staffing is equalizes among units. |

| Predictor | HR (95% CI) | p-Value * | Confounders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q28 | 0.09 (0.02, 0.50) | 0.030 | PU Source PU Local |

| Q17 | 21.54 (1.46, 317.12) | 0.100 | PU Local |

| Q12 | 0.48 (0.05, 4.39) | 0.520 | PU Grade Immobility |

| Q5 | 0.04 (0.00, 0.92) | 0.132 | PU Grade |

| Q3 | 0.20 (0.03, 1.34) | 0.194 | PU Grade Immobility |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Furtado, K.; Voorham, J.; Infante, P.; Afonso, A.; Morais, C.; Lucas, P.; Lopes, M. The Relationship between Nursing Practice Environment and Pressure Ulcer Care Quality in Portugal’s Long-Term Care Units. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1751. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121751

Furtado K, Voorham J, Infante P, Afonso A, Morais C, Lucas P, Lopes M. The Relationship between Nursing Practice Environment and Pressure Ulcer Care Quality in Portugal’s Long-Term Care Units. Healthcare. 2023; 11(12):1751. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121751

Chicago/Turabian StyleFurtado, Katia, Jaco Voorham, Paulo Infante, Anabela Afonso, Clara Morais, Pedro Lucas, and Manuel Lopes. 2023. "The Relationship between Nursing Practice Environment and Pressure Ulcer Care Quality in Portugal’s Long-Term Care Units" Healthcare 11, no. 12: 1751. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121751

APA StyleFurtado, K., Voorham, J., Infante, P., Afonso, A., Morais, C., Lucas, P., & Lopes, M. (2023). The Relationship between Nursing Practice Environment and Pressure Ulcer Care Quality in Portugal’s Long-Term Care Units. Healthcare, 11(12), 1751. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11121751