Abstract

Breast milk is a perfect food for infants; however, the rate of exclusive breastfeeding is low. The relationship between exclusive breastfeeding practices and influencing factors is complex and remains unclear. This cross-sectional study was conducted in Changsha County, China, and 414 mothers were enrolled. An online questionnaire was used to collect data on general information, obstetrics and gynecology characteristics, the initial breastfeeding intention, breastfeeding practice, frequency of attending conventional breastfeeding programs before delivery, the status of breastfeeding self-efficacy, and the status of perceived social support. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to estimate the association between exclusive breastfeeding and potential risk factors of failing to practice exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months. The rate of exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months was 46.1%. The median and interquartile range of the scores for breastfeeding self-efficacy and perceived social support were 51.0 (18.0) and 68.0 (20.0), respectively. Factors that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis were included in the SEM and model fitness was acceptable based on the results. Exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months was directly associated with intention and self-efficacy, while it was indirectly associated with perceived social support and frequency of attending a breastfeeding program. The findings support the recommendation that comprehensive breastfeeding promotion strategies should be implemented to call on the intention and self-efficacy of breastfeeding mothers through various measures, such as education or providing medical and health services.

1. Introduction

Breast milk is the perfect food for infants and breastfeeding, especially exclusive breastfeeding, which provides infants with the best start in physical and mental development and lifelong health benefits [1,2]. Breastfeeding protects against illness and death in children and is beneficial for early childhood development. It decreases the risk of non-communicable diseases, such as childhood asthma, obesity, diabetes, and heart disease in later life [1,3]. On the other hand, breastfeeding promotes mothers’ well-being by improving birth spacing and reducing the risk of illness and disease, such as postpartum hemorrhage, breast cancer, and cardiovascular diseases [1,3]. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), increased breastfeeding could prevent 823,000 deaths in children under five annually, as well as 20,000 deaths due to breast cancer in mothers [3].

Despite the merits of breastfeeding, the rate of exclusive breastfeeding remains low. Indeed, only 37% of infants aged <6 months are exclusively breastfed in LMICs [3]. In China, exclusive breastfeeding rates were also unsatisfactory, ranging from 0.5% to 33.45% at the age of 6 months before 2019 [4,5,6,7,8,9]. This was far below the exclusive breastfeeding target of 50% at 6 months, which was set in the National Program of Action for Child Development in China (2011–2020) [10]. Thus, much effort is needed to scale up the exclusive breastfeeding rate in China.

According to the Cochrane Special Collections: Enabling breastfeeding for mothers and babies, many studies have discussed issues related to exclusive breastfeeding practice, including support for breastfeeding women, health promotion and enabling environments, caring for breastfeeding women and their babies, treatment of breastfeeding problems, and feeding practices for preterm babies/babies with additional needs and their mothers [11]. The factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding can be grouped into four major dimensions: infant, maternal, family, and social [4,6,7,11,12]. However, the results have been inconsistent. For example, Shi H. and colleagues conducted a national survey and reported that several factors were statistically associated with exclusive breastfeeding practices, including maternal age and maternal education [4]. However, Duan Y. et al. analyzed another nationally representative database and reported that the exclusive breastfeeding rate was not significantly associated with maternal age or educational level [7].

In addition, exclusive breastfeeding is influenced to more extent by multiple behavioral and psychological factors, such as intention, self-efficacy, and perceived social support [13,14,15]. Self-efficacy is considered to be related to exclusive breastfeeding; however, the results vary. Vakilian K. and colleagues reported a successful intervention program to improve the exclusive breastfeeding rate through home-based education on self-efficacy, while Monteiro J. and colleagues observed no association between breastfeeding self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding at 1 month postpartum [16,17].

Furthermore, previous studies showed that the above-mentioned influencing factors may affect each other [18,19]. Yang X. and colleagues reported that the intention to breastfeed, partner’s support, support from nurses/midwives, attending antenatal breastfeeding classes, time from childbirth to breastfeeding initiation, and previous breastfeeding experience were predictors of breastfeeding self-efficacy [20]. Kuswara K. and colleagues reported that breastfeeding intention, self-efficacy, and awareness of infant feeding guidelines were key factors associated with sustained exclusive breastfeeding for 4 months [21]. Thus, the intention to breastfeed and social support may be indirectly associated with exclusive breastfeeding via breastfeeding self-efficacy. This complex association can be illustrated by the structural equation modeling (SEM) approach, which is widely used to assess complex relationships and paths of health determinants [22,23,24].

Studies involving behavioral and psychological factors that influence exclusive breastfeeding were limited to Mainland China; two studies conducted among Chinese mothers outside Mainland China were noticed [21,25]. Given the discrepancy in family, social, and cultural backgrounds, the above-mentioned factors differed. Therefore, it is important to investigate the potential effects of these factors on exclusive breastfeeding. This will, in turn, provide healthcare providers with insights to seek interventions to increase the proportion of exclusive breastfeeding practices in Mainland China. In recent years, policies and actions aimed at promoting breastfeeding practices have been implemented in China. The China State Council introduced the National Program of Action for Child Development in China (2011–2020) in 2011, which set a goal of a 50% exclusive breastfeeding rate under 6 months. However, it is unclear whether, in the context of these policies, there is a direct or indirect association between exclusive breastfeeding practices and the aforementioned factors, such as breastfeeding self-efficacy, intention, and social support. With this background in mind, we conducted this study to (1) explore the factors influencing exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months and (2) discuss the mechanism among the influencing factors to increase the exclusive breastfeeding rate in Mainland China.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University (XYGW-2021-036) and conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Trained researchers introduced this study to mothers. Informed consent was obtained from the participants by clicking on the confirmation button on the online questionnaire and participants were able to withdraw consent at any point during or after the survey, in which case the data would be deleted.

2.2. Study Design and Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted at 23 primary medical and health institutions in Changsha County, Hunan Province, from January to February 2021. A total of 414 mothers of infants were enrolled in this study, with 15–20 mothers enrolled per primary medical and health institutions.

The inclusion criteria were (1) mothers who attended any one of these 23 primary medical and health institutions and (2) mothers who gave informed consent. The exclusion criteria were (1) mothers whose babies were younger than 6 months or older than 12 months, (2) mothers who could not practice breastfeeding due to medical concerns, (3) infants who were intolerant to breast milk, and (4) infants who had severe diseases, such as major malformations and genetic diseases.

The required sample size was 271, as calculated by PASS software (version 15.0 for Windows; NCSS LLC, Kaysville, UT, USA), and the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding was 20.8% [26] with an allowable error of 10%. Considering the potential dropouts (20%), the dropout-inflated sample size was 339. Finally, a total of 414 participants were recruited for this study.

2.3. Data Collection

The outcome of interest was breastfeeding practice. An online questionnaire was developed by reviewing the literature and in consultation with experts. The questionnaire was then modified following a pilot survey. The resulting online questionnaire was used to collect the information indicated below.

2.3.1. General Information, Obstetrics and Gynecology Characteristics, and Participation in the Breastfeeding Program

Collected general information included age, ethnicity, education, job, domicile, income, and marital status. Obstetric and gynecological characteristics included the number of children, history of gravidity, history of parturition, history of abortion, age at the last parturition, BMI before the last parturition, history of fetal or infant adverse pregnancy outcomes, delivery method of the last parturition, and history of maternal adverse pregnancy events during the last parturition. We also collected information on the frequency of attending a breastfeeding program.

2.3.2. Breastfeeding Practice

Data on the initial intention and actual practice of breastfeeding were collected by using a self-reported questionnaire. The initial intention of breastfeeding was categorized into four levels: (1) artificial feeding, defined as feeding infants with food or liquids instead of breast milk; (2) mixed feeding, defined as feeding infants with other liquids or foods in addition to breast milk; (3) nearly exclusive breastfeeding, defined as feeding infants mainly with breast milk but providing a small amount of liquids, such as water and juice; and (4) exclusive breastfeeding, defined as feeding infants exclusively with breast milk without other foods or liquids, including water [27]. The actual practice of breastfeeding further was further grouped into two categories: whether or not exclusive breastfeeding was practiced for 6 months.

2.3.3. Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy

The Chinese version of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale of the Short Form was used to measure participants’ breastfeeding confidence [28,29]. The fourteen items were divided into two subscales: technique (items 1, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 13, and 14) and intrapersonal thoughts (items 2, 3, 7, 9, and 12). All items are preceded by the phrase “I can always” and anchored with a 5-point Likert-type scale, where 1 indicates “not at all confident” and 5 indicates “always confident”.

2.3.4. Perceived Social Support

The Chinese version of the Perceived Social Support Scale was used to measure the participants’ social support [30,31]. The 12 items of this scale were designed on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). Perceived adequacy of support from three sources was measured: family (items 3, 4, 8, and 11), friends (items 6, 7, 9, and 12), and significant others (items 1, 2, 5, and 10).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations, and otherwise by medians and interquartile ranges. The normality of the data was determined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Categorical variables are presented as numbers and proportions. Continuous variables were compared using one-way ANOVA or Mann–Whitney U tests; categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to estimate the association between exclusive breastfeeding and potential risk factors of failing to practice exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months. Model fitness was determined using multiple indices including the ratio of the minimum discrepancy and degree of freedom (CMIN/DF), the goodness of fit index (GFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), the normed fit index (NFI), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) [32]. SPSS Amos (version 21.0, IBM, New York, NY, USA) was used for SEM with the maximum likelihood estimation method.

All other statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 25.0, IBM, New York, NY, USA). The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Social Economic Status, Obstetrics and Gynecology, History of Disease, and the Initial Breastfeeding Intention of Participants

A total of 414 participants were enrolled and 46.1% (191/414) of their babies were exclusively breastfed up until 6 months of age. The mean age of the mothers was 30.08 ± 4.41 years and the ethnicity of the vast majority of participants was Han. The mean age of the infants was 8.41 ± 2.32 months. A statistically significant difference in exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months was observed among mothers with different histories of fetal or infant adverse pregnancies, the initial intention of breastfeeding, and frequency of attending breastfeeding programs (all p < 0.05). The details are presented in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

The association between the demographic characteristic of mothers and exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (n = 414).

Table 2.

The association between characteristics of obstetrics and gynecology, history of disease, family history of disease and exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (n = 414).

3.2. Participants’ Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy

Table A1 shows participants’ breastfeeding self-efficacy. The scores for breastfeeding self-efficacy were 51.0 (18.0), 46.0 (19.0), and 56.0 (18.0) for all participants, participants who did not exclusively breastfeed for 6 months, and participants who exclusively breastfed for 6 months, respectively. Statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups (not exclusively breastfed vs. exclusively breastfed), including in the technique subscale score, intrapersonal thoughts subscale score, and total score of breastfeeding self-efficacy (all p < 0.001).

3.3. Perceived Social Support of the Participants

The perceived social support of participants is presented in Table A2. The median and interquartile range of the score of perceived social support was 68.0 (20.0). The scores of the three sources were 24.0 (8.0) for family, 22.0 (7.0) for friends, and 22.0 (7.0) for significant others. Statistically significant differences were observed between groups (not exclusively breastfed vs. exclusively breastfed, all p < 0.05), except for the subscore of significance for other support (p = 0.098).

3.4. Exclusive Breastfeeding for 6 Months in Structural Equation Modeling

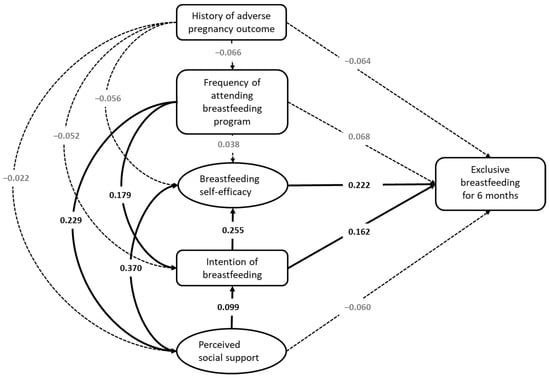

Factors that were statistically significant in the previous analysis were included in the SEM, including a history of fetal or infant adverse pregnancy outcomes, frequency of attending a breastfeeding program, initial intention to breastfeed, the numerical total score of breastfeeding self-efficacy, and perceived social support (Figure 1). Table 3 lists the regression coefficients of the model. The fitness of the model was acceptable: CMIN/DF was 5.45, GFI was 0.71, CFI was 0.87, NFI was 0.84, and SRMR was 0.040.

Figure 1.

Structural equation model of exclusive breastfeeding at the age of 6 months (CMIN/DF = 5.451; GFI = 0.713; CFI = 0.866; NFI = 0.841; and SRMR = 0.0401). The coefficients of p-values higher than 0.05 are in gray and the corresponding paths are depicted with dotted lines. History of adverse pregnancy outcomes refers to adverse pregnancy outcomes relating to fetuses and infants, including embryo damage, extrauterine pregnancy, intrauterine growth retardation, birth defects, hydatidiform moles, neonatal death, low birth weight, premature delivery, macrosomia, and prolonged pregnancy.

Table 3.

The direct, indirect, and total effects of the variables in the structural equation modeling.

Seven of the fifteen paths suggested in the hypothetical model were statistically significant (p < 0.05). The frequency of attending a breastfeeding program directly affected perceived social support and intention (β = 0.229, p = 0.004; β = 0.179, and p = 0.003, respectively) and indirectly affected intention, self-efficacy, and exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (β = 0.023, p = 0.032; β = 0.136, p = 0.002; β = 0.058, and p = 0.002, respectively). Perceived social support directly affected intention and self-efficacy (β = 0.099, p = 0.042; β = 0.370, and p = 0.003, respectively) and indirectly affected self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (β = 0.025, p = 0.028; β = 0.104, and p = 0.002, respectively). Intention directly affected self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (β = 0.225, p = 0.002; β = 0.162, and p = 0.002, respectively) and indirectly affected exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (β = 0.057 and p = 0.001). Self-efficacy directly affected exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (β = 0.222 and p = 0.002). A history of fetal or infant adverse pregnancy outcomes indirectly affected exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (β = −0.033 and p = 0.027).

4. Discussion

In this study, we found that the exclusive breastfeeding rate for 6 months was 46.1% in Changsha County and exclusive breastfeeding was directly associated with the initial intention to breastfeed and breastfeeding self-efficacy by SEM. The findings of this study may help increase exclusive breastfeeding practices in China.

Globally, the exclusive breastfeeding rate is approximately 37% and varies in different countries; the rate in high-income countries (HICs) is lower than the one in LMICs [11]. For example, less than 1% of babies are exclusively breastfed at 6 months in the UK in 2010, whereas approximately 20.7% of babies are exclusively breastfed at 6 months in China in 2013 [7,11]. The exclusive breastfeeding rate in our study was higher than that reported in previous studies conducted in China [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Duan Y. et al. reported the rate of exclusive breastfeeding under 6 months was 20.7% in a national cross-sectional survey conducted in 2013 [7]. Shi H. and colleagues reported a rate of 29.5% in a national cross-sectional survey conducted in 2018 [4]. A study conducted in Changsha reported a rate of 40% between 2013 and 2014 [33]. The discrepancy in the rate between this study and previous studies may be due to the recent advocacy initiative to promote breastfeeding in China. The China State Council introduced the “National Program of Action for Child Development in China (2011–2020)”, which set a goal of a 50% exclusive breastfeeding rate under 6 months [10]. With years of effort, the exclusive breastfeeding rate under 6 months has gradually increased; for example, between 2013 and 2018, it increased from 20.8% to 29.5% on a national level [4,26]. However, the exclusive breastfeeding rate was lower than the goal of 50% by 2020 [10]. A possible reason for this is the misunderstanding of mothers regarding exclusive breastfeeding. In this survey, nearly half of the participants (47.6%) thought that “exclusive breastfeeding refers to feeding infants with breast milk and ‘moderate water’” (data not shown). Mothers enrolled in this study did not realize that additional water was not allowed in exclusive breastfeeding practices. Thus, more work should be performed to correct misunderstandings and educate mothers on exclusive breastfeeding.

This study showed that initial intention to breastfeed was directly related to exclusive breastfeeding under 6 months, which supports the hypothesis that mothers’ strong breastfeeding intentions will lead to exclusive breastfeeding, which echoes the findings of previous studies [13,21,25,34]. Wu S. V. and colleagues observed a higher level of prenatal breastfeeding intention in the breastfeeding group than in the not breastfeeding group (9.80 ± 0.66 versus 8.63 ± 2.01, p = 0.001) [25]. Wilhelm S. L. and colleagues reported that women who intended to practice exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months were two times more likely to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months than those who did not [OR (95% CI): 2.19 (1.01–4.76)] [34]. These findings support the recommendation that healthcare professionals should call on the intentions of breastfeeding mothers.

The results showed that breastfeeding self-efficacy was also directly associated with exclusive breastfeeding practice under 6 months, which is consistent with previous studies [14,35,36,37,38]. A meta-analysis conducted by Brockway M. and colleagues examined the association between breastfeeding self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding by summarizing the studies with interventions on breastfeeding self-efficacy and the resultant exclusive breastfeeding rate [38]. They reported that for each 1-point increase in the mean breastfeeding self-efficacy score between the intervention and control groups, the odds of exclusive breastfeeding increased by 10% in the intervention group. Another meta-analysis observed that educational interventions using the breastfeeding self-efficacy theory were effective in improving the exclusive breastfeeding rate at postpartum 1~2 months [OR (95% CI): 1.69 (1.18–2.42)] [35].

The SEM showed that two factors, initial intention to breastfeed and breastfeeding self-efficacy, were directly associated with exclusive breastfeeding. However, other factors may be indirectly associated with exclusive breastfeeding via the above-mentioned two factors. For example, perceived social support may influence exclusive breastfeeding indirectly through its association with the initial intention of breastfeeding and breastfeeding self-efficacy. In addition, we observed a statistically significant association between the initial intention to breastfeed and self-efficacy. Previous studies have discussed such associations [18,19,20,39,40]. For example, Yang X. and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study in China and found that breastfeeding self-efficacy in the immediate postpartum period could be predicted by the combination of intention to breastfeed, support from partners, support from nurses/midwives, attending antenatal breastfeeding classes, time from childbirth to breastfeeding initiation, and previous breastfeeding experience [20]. In contrast, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis, Mitra A. K. and colleagues reported that breastfeeding intention could be independently predicted by fewer children, past breastfeeding experience, breastfeeding knowledge, self-efficacy, and perceived social support [19]. Our study also found that the frequency of attending a breastfeeding program before delivery was indirectly and positively related to exclusive breastfeeding via initial intention to breastfeed. Thus, a comprehensive program targeting perceived social support, intentions, and self-efficacy of breastfeeding should be developed to increase exclusive breastfeeding rates. For example, the Action Plan for Breastfeeding Promotion (2021–2025) in China was launched in November 2021. This latest action was formulated to ensure the implementation of optimized fertility policies, safeguard the rights and interests of mothers and infants, and promote breastfeeding. The latest plan stipulates the following: 1. Disseminate scientific knowledge and vigorously conduct publicity and education on breastfeeding. 2. Improve the service chain and strive to strengthen breastfeeding consultation and guidance. 3. Improve policies and systems, and strive to build a supportive environment for breastfeeding. 4. Strengthen industry supervision and effectively crack down on illegal behaviors that endanger breastfeeding. This study provides evidence of the exclusive breastfeeding rate among postpartum women, as well as the direct and indirect relationship between exclusive breastfeeding practice, the initial intention of breastfeeding, breastfeeding self-efficacy, and other factors. Due to the limitations of the cross-sectional design and single-county sampling, the extrapolation of conclusions should be cautious. However, the main influencing factors found in this study correspond to the main tasks of China’s Action Plan for Promoting Breastfeeding (2021–2025). Therefore, our research not only provides effective evidence for the latest plan but also shows that the extrapolation of our research conclusions on influencing factors is acceptable. In addition, the result of our study can serve as the baseline data for Hunan Province, which is useful in evaluating the effect of China’s Action Plan for Promoting Breastfeeding (2021–2025). Second, due to the limited sample size, this study addresses only the influence of several maternal characteristics, initial intention, perceived social support, and breastfeeding knowledge. However, if research could be conducted with a larger sample, other potential factors such as infant characteristics, psychological condition, the influence of mass media, and previous breastfeeding experience could be included [12,41,42,43]. Third, data were collected via participant recall and using a self-reported questionnaire that may be subject to recall bias and social desirability bias.

5. Conclusions

The exclusive breastfeeding rate under 6 months in Changsha County was low. This study presents the direct relationship between exclusive breastfeeding practice and initial intention and self-efficacy of breastfeeding, as well as the indirect effect of social support and health education programs on exclusive breastfeeding practice. The findings support the recommendation that comprehensive breastfeeding promotion strategies should be implemented to call on the intention and self-efficacy of breastfeeding mothers through various measures, such as education or providing medical and health services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L. and F.L.; methodology, Q.L. and F.L.; formal analysis, F.L.; investigation, C.H., Y.X., C.X. and C.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, F.L.; writing—review and editing, C.H., Y.X., C.X., C.Y., Q.L. and J.D.; visualization, F.L.; supervision, Q.L.; project administration, Q.L.; funding acquisition, Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, grant number 2020JJ4767.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University (XYGW-2021-036).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their time and cooperation and the health workers and graduate students for assisting with recruitment and data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The association between breastfeeding self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (n = 414).

Table A1.

The association between breastfeeding self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (n = 414).

| Variable | Exclusive Breastfeeding | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Technique subscale score | 30.0 (11.0) | 36.0 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| Intrapersonal thoughts subscale score | 16.0 (8.0) | 20.0 (8.0) | <0.001 |

| Total score of breastfeeding self-efficacy | 46.0 (19.0) | 56.0 (18.0) | <0.001 |

Table A2.

The association between perceived social support and exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (n = 414).

Table A2.

The association between perceived social support and exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (n = 414).

| Variable | Exclusive Breastfeeding | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Family support score | 23.0 (6.0) | 24.0 (8.0) | 0.019 |

| Friends support score | 22.0 (5.0) | 24.0 (9.0) | 0.015 |

| Significant other support score | 22.0 (6.0) | 23.0 (9.0) | 0.098 |

| Total score of perceived social support | 65.0 (16.0) | 70.0 (24.0) | 0.025 |

References

- UNICEF; World Health Organization. Breastfeeding Advocacy Initiative: UNICEF, WHO.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Eidelman, A.I.; Schanler, R.J. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e827–e841. [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.; França, G.V.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016, 387, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Yin, X.; Li, J.; Fang, J.; Wang, X. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months in China: A cross-sectional study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2021, 16, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Tang, K. The Patterns and Social Determinants of Breastfeeding in 12 Selected Regions in China: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. J. Hum. Lact. 2020, 36, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, H.Q.; Xu, J.; Li, L.; Redding, S.R.; Ouyang, Y.Q. The Relationship of Previous Breastfeeding Experiences and Factors Affecting Breastfeeding Rates: A Follow-Up Study. Breastfeed. Med. 2020, 15, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Yang, Z.; Lai, J.; Yu, D.; Chang, S.; Pang, X.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, H.; Bi, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Exclusive Breastfeeding Rate and Complementary Feeding Indicators in China: A National Representative Survey in 2013. Nutrients. 2018, 10, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, W.Y.; Gao, L.L.; Choi, K.C.; Chau, J.P.; Xiao, Y. The Short Form of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale as a Prognostic Factor of Exclusive Breastfeeding among Mandarin-Speaking Chinese Mothers. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 32, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Tian, J.; Xu, F.; Binns, C. Breastfeeding in China: A Review of Changes in the Past Decade. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China State Council. National Program of Action for Child Development in China (2011–2020); China People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Cochrane Library. Cochrane Special Collections: Enabling Breastfeeding for Mothers and Babies. 2017. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/collections/doi/10.1002/14651858.SC000027/full (accessed on 27 November 2022).

- Lau, Y.; Htun, T.P.; Lim, P.I.; Ho-Lim, S.; Klainin-Yobas, P. Maternal, Infant Characteristics, Breastfeeding Techniques, and Initiation: Structural Equation Modeling Approaches. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e142861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazirah, J.; Noraini, M.; Norkhafizah, S.; Tengku, A.T.; Zaharah, S. Intention and actual exclusive breastfeeding practices among women admitted for elective cesarean delivery in Kelantan, Malaysia: A prospective cohort study. Med. J. Malays. 2020, 75, 274–280. [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi, M.; Matsuzaki, M.; Kurihara, S.; Iwamoto, M.; Shimada, M. Post-breastfeeding stress response and breastfeeding self-efficacy as modifiable predictors of exclusive breastfeeding at 3 months postpartum: A prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jantzer, A.M.; Anderson, J.; Kuehl, R.A. Breastfeeding Support in the Workplace: The Relationships among Breastfeeding Support, Work-Life Balance, and Job Satisfaction. J. Hum. Lact. 2018, 34, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, J.; Guimarães, C.; Melo, L.; Bonelli, M. Breastfeeding self-efficacy in adult women and its relationship with exclusive maternal breastfeeding. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 2020, 28, e3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakilian, K.; Farahani, O.; Heidari, T. Enhancing Breastfeeding—Home-Based Education on Self-Efficacy: A Preventive Strategy. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleki-Saghooni, N.; Amel, B.M.; Karimi, F.Z. Investigation of the relationship between social support and breastfeeding self-efficacy in primiparous breastfeeding mothers. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 2020, 33, 3097–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.K.; Khoury, A.J.; Hinton, A.W.; Carothers, C. Predictors of breastfeeding intention among low-income women. Matern. Child Health J. 2004, 8, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gao, L.; Ip, W.; Chan, W.C.S. Predictors of breast feeding self-efficacy in the immediate postpartum period: A cross-sectional study. Midwifery 2016, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuswara, K.; Campbell, K.J.; Hesketh, K.D.; Zheng, M.; Laws, R. Patterns and predictors of exclusive breastfeeding in Chinese Australian mothers: A cross sectional study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2020, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, J.D.; Simpson, J.; Worsfold, C.; Fisher, K. A structural equation modelling approach to the complex path from postural stability to morale in elderly people with fear of falling. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, R.L.; Williams, S.M.; Costa-Ribeiro, H.; Mattos, A.P.; Barreto, D.L.; Houghton, L.A.; Bailey, K.B.; Lander, A.G.; Gibson, R.S. Understanding the complex determinants of height and adiposity in disadvantaged daycare preschoolers in Salvador, NE Brazil through structural equation modelling. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, A.; Ningrum, V.; Lee, A.; Hsu, W.K.; Amalia, R.; Dewanto, I.; Lee, S.C. Structural equation modelling of the complex relationship between toothache and its associated factors among Indonesian children. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.V.; Chen, S.C.; Liu, H.Y.; Lee, H.L.; Lin, Y.E. Knowledge, Intention, and Self-Efficacy Associated with Breastfeeding: Impact of These Factors on Breastfeeding during Postpartum Hospital Stays in Taiwanese Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Lai, J.; Yu, D.; Duan, Y.; Pang, X.; Jiang, S.; Bi, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.; Yin, S. Breastfeeding rates in China: A cross-sectional survey and estimate of benefits of improvement. Lancet 2016, 388, S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Breastfeeding. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_2 (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Dennis, C.L. The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale: Psychometric assessment of the short form. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal. Nurs. 2003, 32, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.Z. A Study on the Association between Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy and Satisfaction of Puerperae in Mother Friendly Hospital; Sun Yat-Sen University: Guangzhou, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.D.; Powell, S.S.; Farley, G.K.; Werkman, S.; Berkoff, K.A. Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 1990, 55, 610–617. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.D.; Wang, X.L.; Ma, H. Rating Scale for Mental Health; Chinese Mental Health Journal: Beijing, China, 1999; p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Kircaburun, K.; Yurdagül, C.; Kuss, D.; Emirtekin, E.; Griffiths, M.D. Problematic Mukbang Watching and Its Relationship to Disordered Eating and Internet Addiction: A Pilot Study Among Emerging Adult Mukbang Watchers. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 2160–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.N.; Kuang, Y.; Hou, D.; Xie, D.H.; Zhang, J.J. The condition of breastfeeding and its influence factors in Changsha. Pract. Prev. Med. 2017, 24, 210–212. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, S.L.; Rodehorst, T.K.; Stepans, M.B.; Hertzog, M.; Berens, C. Influence of intention and self-efficacy levels on duration of breastfeeding for midwest rural mothers. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2008, 21, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipojola, R.; Chiu, H.Y.; Huda, M.H.; Lin, Y.M.; Kuo, S.Y. Effectiveness of theory-based educational interventions on breastfeeding self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 109, 103675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roza, J.G.; Fong, M.K.; Ang, B.L.; Sadon, R.B.; Koh, E.; Teo, S. Exclusive breastfeeding, breastfeeding self-efficacy and perception of milk supply among mothers in Singapore: A longitudinal study. Midwifery 2019, 79, 102532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khresheh, R.M.; Ahmad, N.M. Breastfeeding self efficacy among pregnant women in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2018, 39, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockway, M.; Benzies, K.; Hayden, K.A. Interventions to Improve Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy and Resultant Breastfeeding Rates: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Hum. Lact. 2017, 33, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, L.; Chou, H.F.; Gau, M.L.; Liu, C.Y. Breastfeeding self-efficacy and related factors in postpartum Vietnamese women. Midwifery 2019, 70, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Chan, W.C.; Zhou, X.; Ye, B.; He, H.G. Predictors of breast feeding self-efficacy among Chinese mothers: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Midwifery 2014, 30, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Y.Y.; Shen, Q.; Zhou, W.B.; Redding, S.R.; Ouyang, Y.Q. Experience predicts the duration of exclusive breastfeeding: The serial mediating roles of attitude and self-efficacy. Birth 2021, 48, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Kim, S.S.; Nguyen, T.T.; Hajeebhoy, N.; Tran, L.M.; Alayon, S.; Ruel, M.T.; Rawat, R.; Frongillo, E.A.; Menon, P. Exposure to mass media and interpersonal counseling has additive effects on exclusive breastfeeding and its psychosocial determinants among Vietnamese mothers. Matern. Child Nutr. 2016, 12, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Henshaw, E.J.; Fried, R.; Siskind, E.; Newhouse, L.; Cooper, M. Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy, Mood, and Breastfeeding Outcomes among Primiparous Women. J. Hum. Lact. 2015, 31, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).