How Differential Dimensions of Social Media Overload Influences Young People’s Fatigue and Negative Coping during Prolonged COVID-19 Pandemic? Insights from a Technostress Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

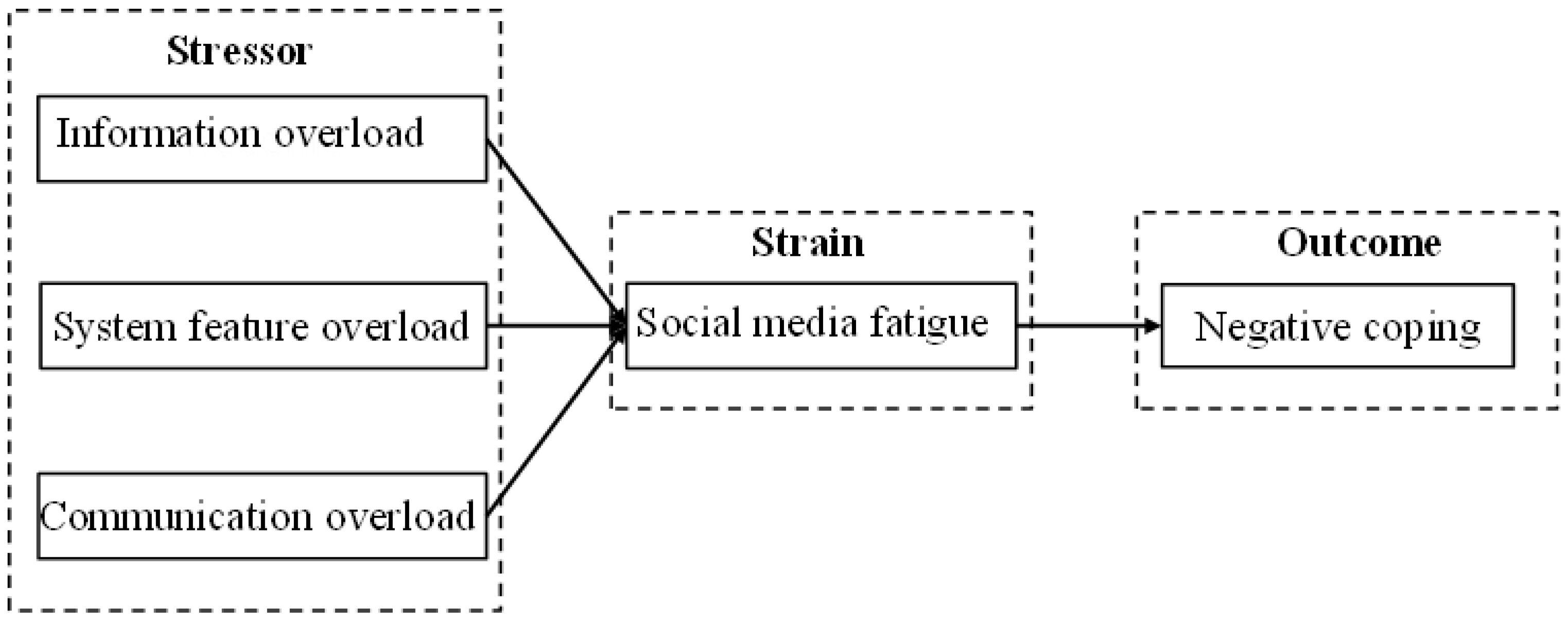

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Formulation

2.1. Stressor–Strain–Outcome (SSO) Theoretical Paradigm

2.2. The Association between Perceived Overload and Social Media Fatigue

2.3. The Association between Social Media Fatigue and Negative Coping

2.4. The Association between Social Media Overload and Negative Coping

3. Study Model and Methodology

3.1. Study Model

3.2. Participants and Procedure

3.3. Construct Measurement

3.3.1. Information Overload

3.3.2. System Feature Overload

3.3.3. Communication Overload

3.3.4. Social Media Fatigue

3.3.5. Negative Coping

3.3.6. Socio-Demographic Variables

4. Data Evaluation

5. Study Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Zero-Order Correlation between Research Variables

5.3. Assessment of Path Model

6. Discussion

6.1. Summary of the Main Results

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Potential Research Directions

7. Closing Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measurements

- Information overload (IFO)

- IFO1: I am always distracted by excessive amount of COVID-19-related information on WeChat.

- IFO2: I have to deal with too much COVID-19-related information every day that I get from WeChat.

- IFO3: I’m having trouble synthesizing too much COVID-19-related information on WeChat.

- System feature overload (SFO)

- SFO1: I’m frequently distracted by WeChat features unrelated to my core aim.

- SFO2: WeChat is helpful by providing elements that make social performance more difficult.

- SFO3: The WeChat features I utilize are sometimes more complicated than their duties.

- Communication overload (CMO):

- CMO1: I get too many messages from friends or acquaintances through WeChat

- CMO2: I send more messages to friends than I wish to on WeChat.

- CMO3: I receive too many WeChat alerts when doing other things.

- CMO4: I always feel overloaded with communication from WeChat.

- CMO5: I get more communication messages and news than I can handle on WeChat.

- Social Media Fatigue (SMF):

- SMF1: I feel frustrated when using WeChat these days.

- SMF2: I feel emotionally drained after using WeChat these days.

- SMF3: I feel irritable after using WeChat for hours these days.

- Negative Coping (NGC):

- NGC1: Today, I wish I could alter what occurred or how I felt.

- NGC2: Today, I fantasized about a better time or location than the one I was in.

- NGC3: I had thoughts or hopes about how things would turn out today.

References

- Zhong, B.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Q. Mental health toll from the coronavirus: Social media usage reveals Wuhan residents’ depression and secondary trauma in the COVID-19 outbreak. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Lu, Z.; Kuang, H.; Wang, C. Information avoidance behavior on social network sites: Information irrelevance, overload, and the moderating role of time pressure. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; Hon, L. How social ties contribute to collective actions on social media: A social capital approach. Public Relat. Rev. 2019, 45, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reer, F.; Tang, W.Y.; Quandt, T. Psychosocial well-being and social media engagement: The mediating roles of social comparison orientation and fear of missing out. New Media Soc. 2019, 21, 1486–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, H.; Zheng, J. Information quality, media richness, and negative coping: A daily research during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 176, 110774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiter, C.R.; Brophy, N.S. Social support and aggressive communication on social network sites during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Commun. 2022, 37, 1295–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.A.; Fan, T.; Toma, C.L.; Scherr, S. International students’ psychosocial well-being and social media use at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: A latent profile analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 137, 107409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokouhyar, S.; Siadat, S.H.; Razavi, M.K. How social influence and personality affect users’ social network fatigue and discontinuance behavior. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 70, 344–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchioli, M.; Ferrucci, R.; Guidetti, M.; Canevini, M.P.; Pravettoni, G.; Galli, F. What will be the impact of the Covid-19 quarantine on psychological distress? Considerations based on a systematic review of pandemic outbreaks. Healthcare 2021, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.N.; Mäntymäki, M.; Laato, S.; Turel, O. Adverse consequences of emotional support seeking through social network sites in coping with stress from a global pandemic. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 62, 102431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, W.; Yoganathan, V.; Osburg, V.-S. COVID-19 information overload and generation Z’s social media discontinuance intention during the pandemic lockdown. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 166, 120600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Liu, F.; Shang, M.; Zhou, X. Toward street vending in post COVID-19 China: Social networking services information overload and switching intention. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, W.; He, C.; Tang, X. Why do people browse and post on WeChat moments? Relationships among fear of missing out, strategic self-presentation, and online social anxiety. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, H. Connecting mobile social media with psychosocial well-being: Understanding relationship between WeChat involvement, network characteristics, online capital and life satisfaction. Soc. Netw. 2022, 68, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L.; Liu, D.; Luo, J. Explicating user negative behavior toward social media: An exploratory examination based on stressor–strain–outcome model. Cogn. Technol. Work 2022, 24, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Kwok, R.C.-W.; Lowry, P.B.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J. The influence of role stress on self-disclosure on social networking sites: A conservation of resources perspective. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 103147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armiya’u, A.Y.u.; Yıldırım, M.; Muhammad, A.; Tanhan, A.; Young, J.S. Mental health facilitators and barriers during Covid-19 in Nigeria. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2022, 2022, 00219096221111354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islm, T.; Meng, H.; Pitafi, A.H.; Zafar, A.U.; Sheikh, Z.; Mubarik, M.S.; Liang, X. Why DO citizens engage in government social media accounts during COVID-19 pandemic? A comparative study. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 62, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Cao, X. The balancing mechanism of social networking overuse and rational usage. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieh, C.; Dale, R.; Jesser, A.; Probst, T.; Plener, P.L.; Humer, E. The impact of migration status on adolescents’ mental health during COVID-19. Healthcare 2022, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Bao, Z. Why people use social networking sites passively: An empirical study integrating impression management concern, privacy concern, and SNS fatigue. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 70, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeske, G.F.; Koeske, R.D. A preliminary test of a stress-strain-outcome model for reconceptualizing the burnout phenomenon. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 1993, 17, 107–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Yossatorn, Y.; Kaur, P.; Chen, S. Online social media fatigue and psychological wellbeing—A study of compulsive use, fear of missing out, fatigue, anxiety and depression. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 40, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prost, S.G.; Lemieux, C.M.; Ai, A.L. Social work students in the aftermath of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita: Correlates of post-disaster substance use as a negative coping mechanism. Soc. Work Educ. 2016, 35, 825–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Pirkkalainen, H.; Salo, M. Social media overload, exhaustion, and use discontinuance: Examining the effects of information overload, system feature overload, and social overload. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Fritz, C. Recovery from job stress: The stressor-detachment model as an integrative framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, S72–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.; Wang, Q. Technostress from Smartphone Use and Its Impact on University Students’ Sleep Quality and Academic Performance. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2022, 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.R.; Son, S.-M.; Kim, K.K. Information and communication technology overload and social networking service fatigue: A stress perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Lee, H.E.; Kim, H. Effects of communication-oriented overload in mobile instant messaging on role stressors, burnout, and turnover intention in the workplace. Int. J. Commun. 2019, 13, 1743–1763. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.-Z.; Tsai, N.-C. The effects of negative information-related incidents on social media discontinuance intention: Evidence from SEM and fsQCA. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 56, 101503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H. Examining associations between university students’ mobile social media use, online self-presentation, social support and sense of belonging. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 72, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karr-Wisniewski, P.; Lu, Y. When more is too much: Operationalizing technology overload and exploring its impact on knowledge worker productivity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Wang, J.; Hu, X. Understanding the Potential Influence of WeChat Engagement on Bonding Capital, Bridging Capital, and Electronic Word-of-Mouth Intention. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, F.; Du, J.; Khan, I.; Fateh, A.; Shahbaz, M.; Abbas, A.; Wattoo, M.U. Perceived threat of COVID-19 contagion and frontline paramedics’ agonistic behaviour: Employing a stressor–strain–outcome perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, A.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Johri, A. Correlates of social media fatigue and academic performance decrement: A large cross-sectional study. Inf. Technol. People 2020, 34, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F.; Renkl, A.; Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory: Instructional implications of the interaction between information structures and cognitive architecture. Instr. Sci. 2004, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, C.J.; Chang, E.C.; Xu, J.; Shen, J.; Zheng, S.; Wang, Y. Basic psychological needs and negative affective conditions in Chinese adolescents: Does coping still matter? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 179, 110889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Yin, Q.; Cai, W.; Song, X.; Deng, W.; Zhang, J.; Deng, G. Posttraumatic stress symptoms among health care workers during the COVID-19 epidemic: The roles of negative coping and fatigue. Psychol. Health Med. 2022, 27, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yagon, M. Socioemotional and behavioral adjustment among school-age children with learning disabilities: The moderating role of maternal personal resources. J. Spec. Educ. 2007, 40, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Su, Y.; Lv, X.; Liu, Q.; Wang, G.; Wei, J.; Zhu, G.; Chen, Q.; Tian, H.; Zhang, K. Perceived stressfulness mediates the effects of subjective social support and negative coping style on suicide risk in Chinese patients with major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 265, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, H.; Jia, R.; Li, Z. Gratitude and problem behaviors in adolescents: The mediating roles of positive and negative coping styles. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Mou, J. Social media fatigue-Technological antecedents and the moderating roles of personality traits: The case of WeChat. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Liu, J.; Lu, J. Tackling fake news in socially mediated public spheres: A comparison of Weibo and WeChat. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 102004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Han, S.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C. To WeChat or to more chat during learning? The relationship between WeChat and learning from the perspective of university students. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 1813–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Xiao, X. From WeChat to “We set”: Exploring the intermedia agenda-setting effects across WeChat public accounts, party newspaper and metropolitan newspapers in China. Chin. J. Commun. 2020, 14, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H. Identifying associations between mobile social media users’ perceived values, attitude, satisfaction, and eWOM engagement: The moderating role of affective factors. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 59, 101561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyumgaç, I.; Tanhan, A.; Kiymaz, M.S. Understanding the most important facilitators and barriers for online education during COVID-19 through online photovoice methodology. Int. J. High. Educ. 2021, 10, 166–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanhan, A.; Arslan, G.; Yavuz, F.; Young, J.S.; Çiçek, İ.; Akkurt, M.N.; Ulus, İ.Ç.; Görünmek, E.; Demir, R.; Kürker, F. A constructive understanding of mental health facilitators and barriers through Online Photovoice (OPV) during COVID-19. ESAM Ekon. Sos. Araştırmalar Derg. 2021, 2, 214–249. [Google Scholar]

| Respondents | Category | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 319 | 51.6 |

| Female | 299 | 48.4 | |

| Age | 18–20 | 42 | 6.8 |

| 21–23 | 261 | 42.2 | |

| 24–26 | 249 | 40.3 | |

| 27–29 | 56 | 9.1 | |

| 30–32 | 10 | 1.6 | |

| Education background | High school or below | 12 | 1.9 |

| Undergraduatedegree | 436 | 70.6 | |

| Postgraduate degree | 162 | 26.2 | |

| Doctoral degree | 8 | 1.3 | |

| WeChat using experience | <1 year | 1 | 0.2 |

| 1–2 years | 15 | 2.4 | |

| 2–3 years | 32 | 5.2 | |

| 3–4 years | 67 | 10.8 | |

| >4 years | 503 | 81.4 | |

| Daily duration of WeChat use | <1 h | 20 | 3.2 |

| 1–2 h | 124 | 20.1 | |

| 2–3 h | 177 | 28.6 | |

| 3–4 h | 142 | 23.0 | |

| >4 h | 155 | 25.1 | |

| Number of WeChat friends | <100 | 33 | 5.3 |

| 101–200 | 80 | 12.9 | |

| 201–300 | 115 | 18.6 | |

| 301–400 | 113 | 18.3 | |

| >400 | 277 | 44.8 |

| Key Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Information overload | 1 | ||||

| 2. System feature overload | 0.537 ** | 1 | |||

| 3. Communication overload | 0.459 ** | 0.386 ** | 1 | ||

| 4. Social media fatigue | 0.329 ** | 0.254 * | 0.256 ** | 1 | |

| 5. Negative coping | 0.334 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.366 ** | 0.483 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pang, H.; Ji, M.; Hu, X. How Differential Dimensions of Social Media Overload Influences Young People’s Fatigue and Negative Coping during Prolonged COVID-19 Pandemic? Insights from a Technostress Perspective. Healthcare 2023, 11, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010006

Pang H, Ji M, Hu X. How Differential Dimensions of Social Media Overload Influences Young People’s Fatigue and Negative Coping during Prolonged COVID-19 Pandemic? Insights from a Technostress Perspective. Healthcare. 2023; 11(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010006

Chicago/Turabian StylePang, Hua, Min Ji, and Xiang Hu. 2023. "How Differential Dimensions of Social Media Overload Influences Young People’s Fatigue and Negative Coping during Prolonged COVID-19 Pandemic? Insights from a Technostress Perspective" Healthcare 11, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010006

APA StylePang, H., Ji, M., & Hu, X. (2023). How Differential Dimensions of Social Media Overload Influences Young People’s Fatigue and Negative Coping during Prolonged COVID-19 Pandemic? Insights from a Technostress Perspective. Healthcare, 11(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010006