Childhood Cancer and the Family: A Pilot Proposal for Comprehensive Intervention at the Time of Diagnosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- 1.

- To describe indicators based on the reality of onco-pediatric patients’ families.

- 2.

- To find out the impact of the diagnosis of the disease on the family’s social support network and their quality of life.

- 3.

- To infer possible indicators for analyzing interventions developed to date.

3. Childhood Cancer and Family: Current Situation

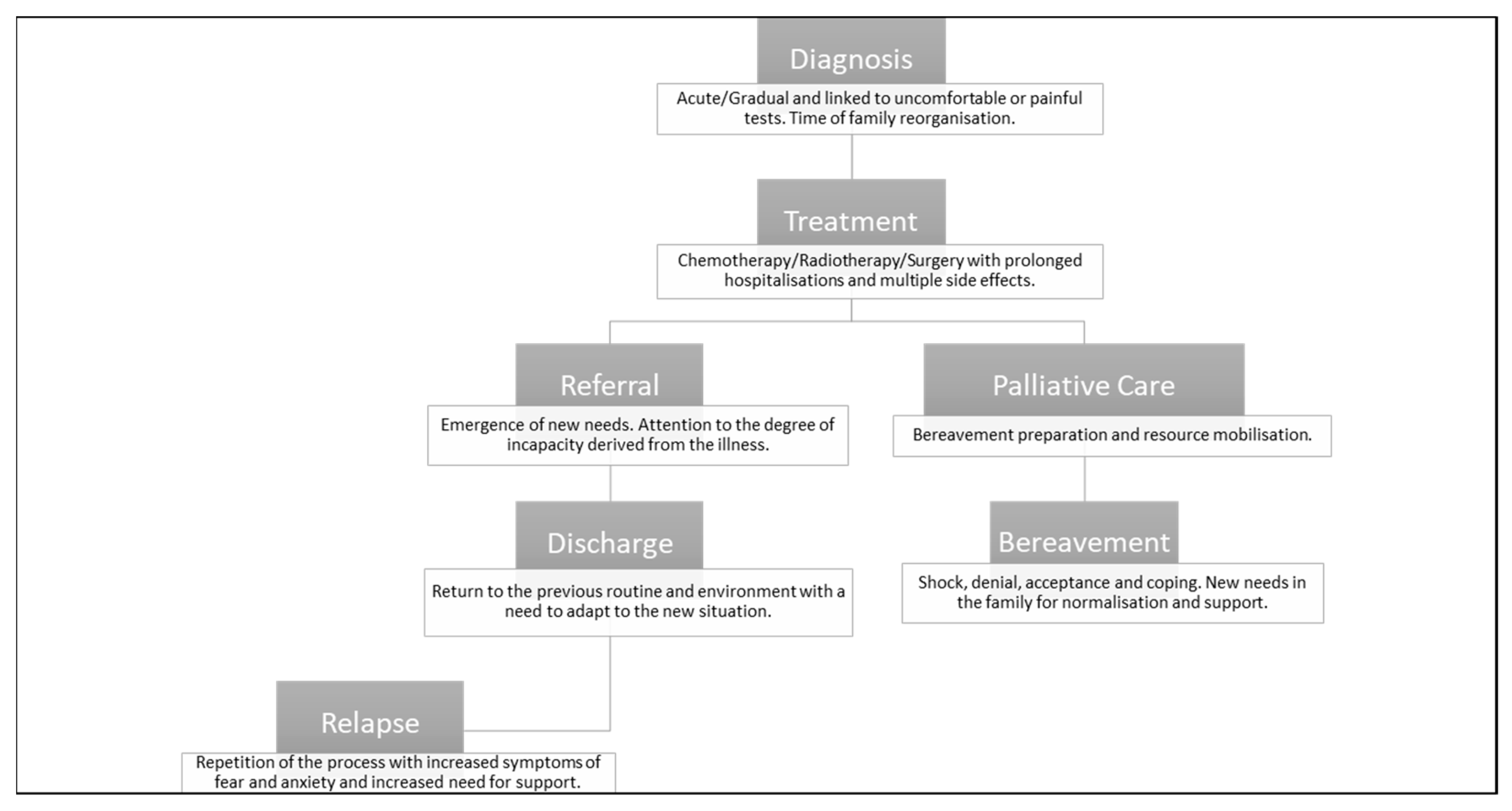

3.1. Contextualisation: Treatment and Sequelae

“This is a long treatment and it’s a hard treatment, from which you get out but you cannot run (...) Cancer is a word that yes, it gives horror, but cancer does not mean death, it means that you go through a lot of things but you can get out, you can come back.”(Informant 5)

“The worst moment of my life was those days (...) I needed to catch my breath (...) I was totally gone and with the vision of my dead son”.(Informant 4)

“I couldn’t believe it (...) you don’t know which way the air blows (...) I couldn’t find comfort anywhere.”(Informant 5)

“All this leaves some very important after-effects and not only cancer, but all serious illnesses, leave family and personal after-effects which you have to be working all day long.”(Informant 5)

3.2. Childhood Cancer Impact on the Family

“What worries you most is what is going to happen tomorrow, what am I going to do with my work, what am I going to do with my other children, how long is this going to last, and that is something you’ve to learn to focus on (...) They told me not to ask so many questions, because this may or may not happen, but I wanted to have everything under control, because when I have everything under control it seems like you know how to handle it, but when I do not, I have learned that you cannot control everything.”(Informant 5)

“I do not think he wasn’t aware, while he was in treatment he was not aware, of course he was 5 years old and wasn’t aware. He went to the hospital to play, in fact, he was more at ease than at home (...) Afterwards, yes, he himself says “how lucky I was to be as old as I was and not find out at the time” (...) I miss the availability I had when I was in hospital: I was always ready to play, I was never tired, afterwards I didn’t do it, not before either, I will value that year all my life.”(Informant 4)

“Communication with families is important so that the child knows what he/she has. We have come across, for example, a case of a 17-year-old who thought that what he had was appendicitis, and no, it was cancer.”(Informant 3)

“They transmit confidence, the medical team, from nurses to everyone, they transmit confidence and it’s fundamental. (...) there are children who go to the hospital crying, too, but the fewest, and little by little you see a total change in them, of at first total rejection and then assimilating it and in the end, I go because they are not going to do anything to me that they don’t have to do to me. It is up to them to transmit that. (...) And parents, too, they tell us “whatever I have to tell you I will tell you whether it’s good or bad”, so you no longer go with fear.”(Informant 4)

“The grandparents are a fundamental pillar because if the mother or father has to be replaced because they have to work, there is the grandmother; if they have to cook, there is the grandmother; if the day you leave the hospital you don’t have time, there is the grandmother. Even if she is not here (in the hospital), because I had my mother here with me, but I had my mother-in-law with my little girl, if my mother-in-law had not been here I do not know what would have happened. I would have had to be with my mother and I would have had to be alone.”(Informant 5)

“You need someone to pick you up and take care of you and pamper you and you can talk so that you can recover and help your child and the rest of the family, which is important (...) Communicating it to the rest of the people around you, not the closest people, was complicated, they were not very close but they were not strangers either. They would ask you and, when I told them, I remember that the face of the person in front of me would change completely, that face was the one that killed me (...) There came a moment when I decided” “I am not going to tell, when I can, I will tell”.(Informant 5)

3.3. Family Intervention in the Childhood Cancer Diagnosis

“Always tell the truth and let the parents break the news to the child, allowing them to ask. The process would be more or less: the doctors tell the parents, who try to cross-check the information, and then they should tell the children.”(Informant 3)

4. Proposal for a Family Intervention Protocol for Comprehensive Care at the Time of Childhood Cancer Diagnosis

- 1.

- Adapt to the patient reality, with the best interests of the child prevailing;

- 2.

- Respect the individuality of the relatives;

- 3.

- Enhance the capacities of parents, guardians or custodians;

- 4.

- To enhance the child self-protection and resilience factors;

- 5.

- Networking.

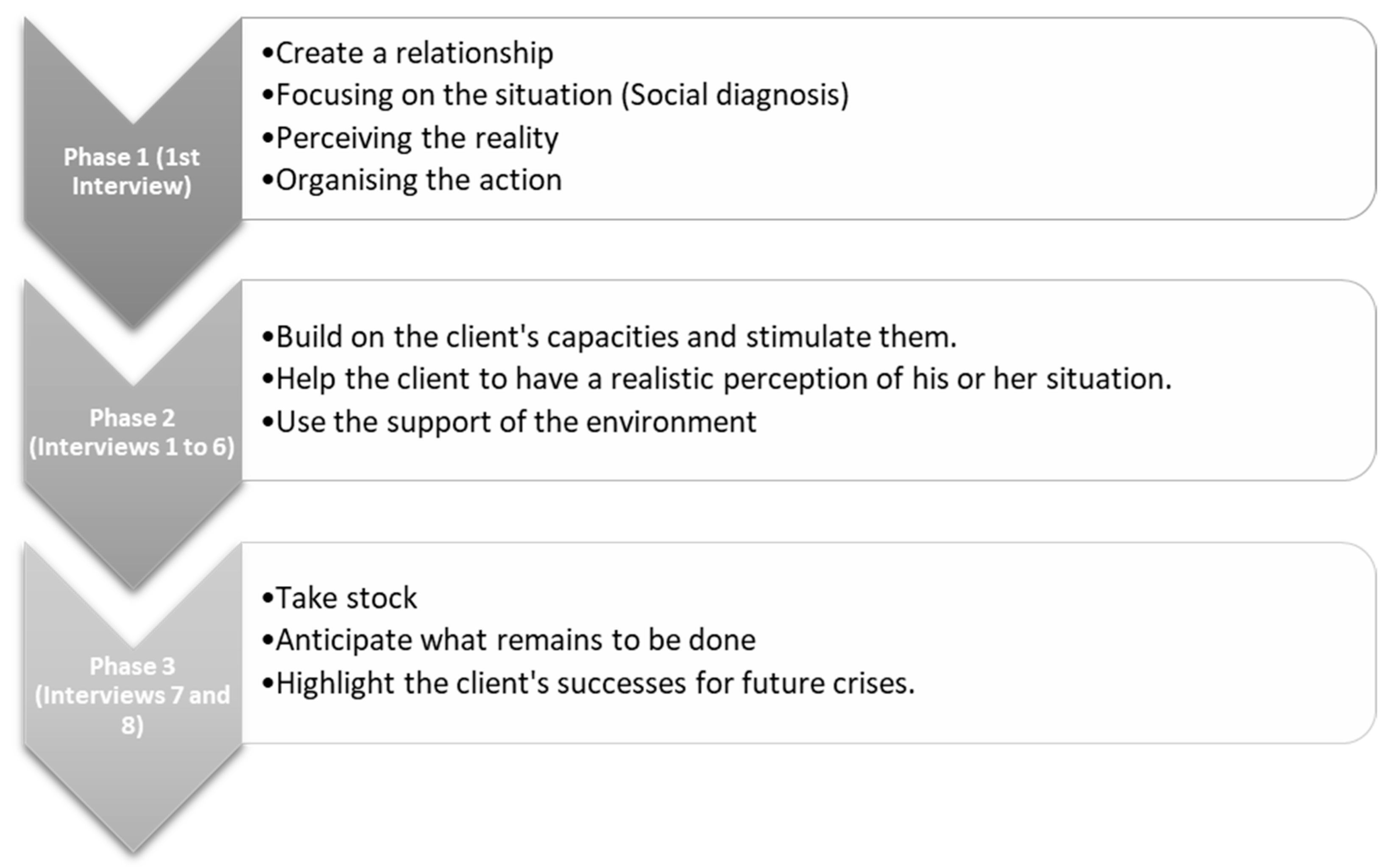

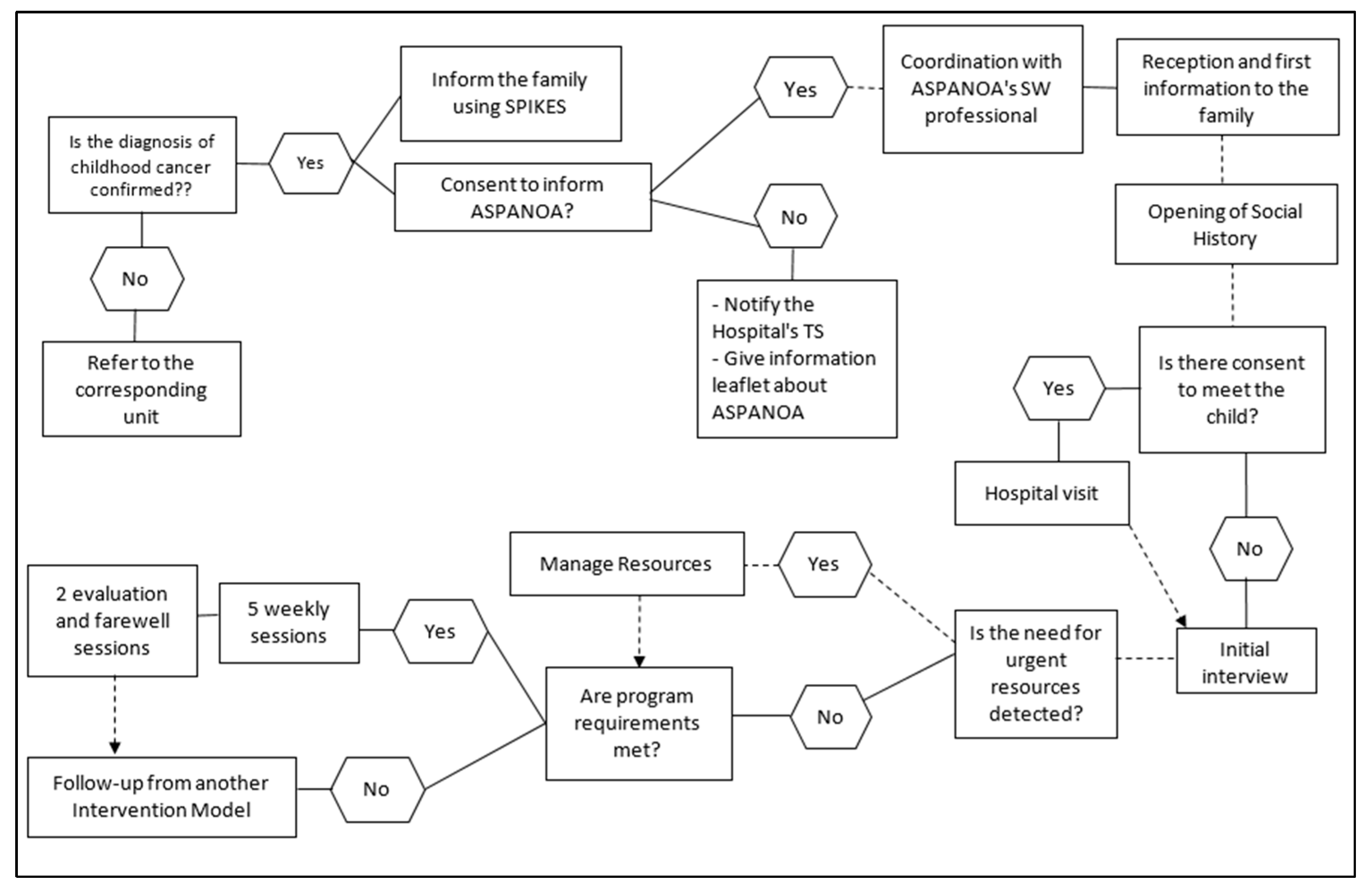

- 1.

- Coordination. The referring doctor will coordinate with ASPANOA through the Hospital social worker, who will request ASPANOA’s collaboration for support after the diagnosis.

- 2.

- Reception and initial information for the family. The doctor introduces the social worker to family. Through the presentation of the entity as a resource and the delivery of informative material, first contact will be made with the family that will allow a relationship of trust to be established with them. The social history will be opened.

- 3.

- Hospital visit. Presentation with the child, if the family gives their consent.

- 4.

- Initial interview, which will be carried out as soon as the parents allow it, trying to make them feel welcome but not overwhelmed by the information. The objectives will be:

- a.

- Deepening the relationship of trust, emotional support and accompaniment.

- b.

- Establishing the social, work, economic, school and family situation.

- c.

- Lack of resources (personal skills, language problems, economic deprivation, lack of support, etc.);

- Need for accommodation;

- Altered roles and relationships in the family environment;

- Need for diet for caregivers;

- Employment parents’ difficulties (exploring moonlighting or no possibility of taking leave to cover care needs);

- Child school situation (exploring possible conflicts);

- Existence of relatives with an illness/disability;

- Existence of other children at home;

- Overburdening of caregivers;

- Family experiences of traumatic situations;

- Experiences of health neglect;

- d.

- Identify family and child protection factors.

- 5.

- Association resource management and coordination with the professionals involved, in order to pool the factors that need to be taken into consideration when dealing with the disease. Coordination with ASPANOA volunteers so that they can support the family.

- 6.

- Five weekly family follow-up sessions, which will be distributed according to the family situation and the illness, and some of the sessions may be devoted solely to emotional support and containment. These sessions will address the following issues:

- e.

- Fostering a relationship of trust and clarification of doubts.

- f.

- Attention to latent needs that have not previously arisen. Follow-up of the resources provided and evaluation of their usefulness.

- g.

- Addressing diagnosis communication and support to the extended family, the child and siblings (if any), and the support network, such as grandparents. Tools and strategies will be offered to facilitate this communication, strengths will be promoted and support will be given in answering possible questions. The resolution of doubts through the healthcare team will be recommended.

- h.

- Support in family reorganization and decision-making based on co-responsible participation, with the child and their siblings, if any.

- i.

- Family intervention with a view to adapting to the new reality, maintaining behavioral guidelines and adapting rules. Special attention should be paid in the event that there are more children in order to avoid possible conflicts or harm to them.

- j.

- Sustenance for relations with the support network and maintenance of leisure and recreational spaces for the parents, favoring spaces for self-care and distraction, with the possibility of using voluntary resources.

- 7.

- Conducting two weekly interviews aimed at closing the intervention, evaluation and preparation for a follow-up during the disease process, bearing in mind that the work will continue using other intervention models. It should be made clear that an ASPANOA social worker and psychologist will be at the hospital and at the association’s headquarters at the family’s disposal, monitoring and accompanying them throughout the illness, helping the hospital social worker. Their main objectives will be:

- k.

- Take stock of the reaction and changes experienced.

- l.

- Highlight the positive and reinforcing elements detected.

- m.

- Prepare for future changes or crises throughout the illness and its aftermath.

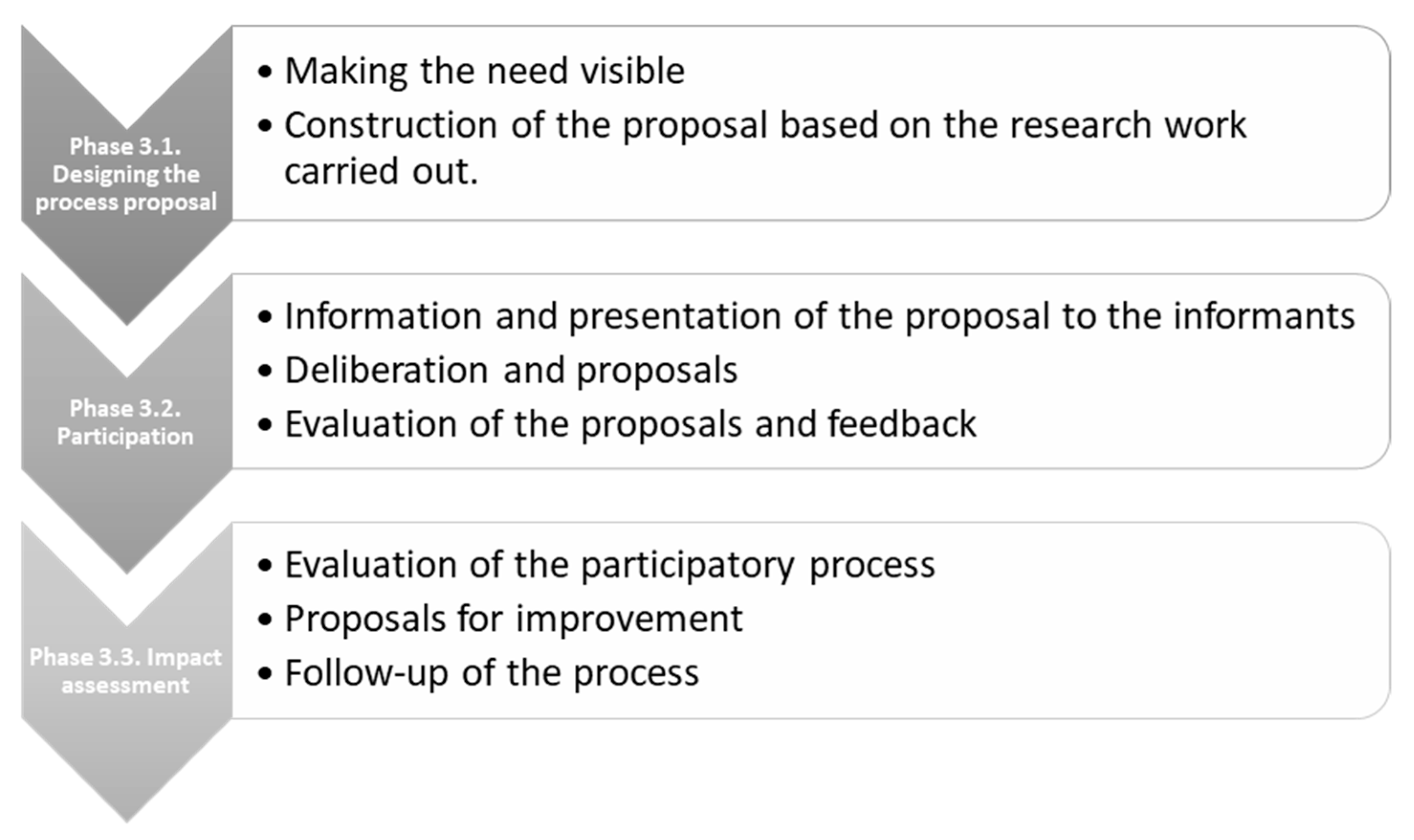

- 1.

- Coverage assessment: how many families have been served and what are their characteristics.

- 2.

- Evaluation of process: intervention carried out and resources used.

- 3.

- Evaluation of results such as: degree of coverage, problem solving, resources used, family evolution or reason for termination of the intervention.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Situation Diagnosis

5.2. Coping with Childhood Cancer by Those Affected, Their Family and Close Environment

5.3. Proposals to Develop

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pitillas Salvá, C. La Importancia del Comportamiento de los Padres Cuando un hijo Tiene Cáncer. Asociación de Padres de Niños con Cáncer ASION. 2014. Available online: http://www.asion.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/La-importancia-del-comportamiento-de-los-padres-cuando-un-hijo-tiene-cancer.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Novellas Aguirre de Carcer, A. Modelo de Trabajo Social en la Atención Oncológica. Institut Catalá d´Oncologia (ICO). 2004. Available online: http://ico.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/ico/professionals/documents/qualy/arxius/doc_modelo_trabajo_social_at._oncologica.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Santrock, J. Psicología del Desarrollo en la Infancia; McGraw-Hill Interamericana: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Scope and Standards of Practice. Association of Oncology Social Work (APOSW). Available online: https://aosw.org/publications-media/scope-of-practice/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Jones, B.; Currin-McCulloch, J.; Pelletier, W.; Sardi-Brown, V.; Brown, P.; Wiener, L. Psychosocial standards of care for children with cancer and their families: A national survey of pediatric oncology social workers. Soc. Work Health Care 2018, 57, 221–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiener, L. The impact of COVID-19 on the professional and personal lives of pediatric oncology social workers. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2021, 39, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, S.; Chow, E.; DBioethics, B.H. The role of social work in the long-term care of childhood cancer survivors: A literature review. J. Pain Manag. 2017, 10, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCubbin, M.; Balling, K.; Possin, P.; Frierdich, S.; Bryne, B. Family Resiliency in Childhood Cancer. Fam. Relat. 2002, 51, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pediatric Oncology Social Workers Help Families Move from Fear to Hope. American Cancer Society. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/latest-news/pediatric-oncology-social-workers-help-families-move-from-fear-to-hope.html (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Arenas Rojas, A.; Val, E.T.; Fernández, M.G. Intervención familiar en diagnóstico reciente e inicio de tratamiento de cáncer infantil. Apunt. Psicol. 2016, 34, 213–220. Available online: https://www.apuntesdepsicologia.es/index.php/revista/article/view/612 (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Consejo General del Trabajo Social (CGTS). Código Deontológico de Trabajo Social. Available online: http://www.trabajosocialaragon.es/colegio/2012-CODIGO_DEONTOLOGICO.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Beerbower, E.; Winters, D.; Kondrat, D. Bio-psychosocial-spiritual needs of adolescents and young adults with life-threatening illnesses: Implications for social work practice. Soc. Work Health Care 2018, 57, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federación Española de Padres de Niños con Cáncer. Available online: https://cancerinfantil.org (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical background and procedures. In Approaches to Qualitative Research in Mathematics Education: Examples of Methodology and Methods; Bikner-Ahsbahs, A., Knipping, C., Presmeg, N.C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Herrero, M.A.; Fuster Ribera, R.; Illa Lahuerta, C.; López Sanmiguel, M. Protocolos de intervención en el trabajo social hospitalario. In Guía de Intervención de Trabajo Social Sanitario; de Salut, A.V., Ed.; Generalitat Valenciana, 2012; Available online: http://publicaciones.san.gva.es/cas/prof/guia_ITSS/capitulo3/Protocolos_intervencion_TS_centros_hospialarios.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Grupo de Trabajo de Enfermería Basada en la Evidencia de Aragón (IACS). Guía Metodológica para la Elaboración de Protocolos Basados en la Evidencia; Instituto Aragonés de Ciencias de la Salud. 2009. Available online: http://www.iacs.es/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/guia-.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Equipo de Trabajo de la Subdirección de Protección a la Infancia y Tutela de Zaragoza. Protocolo de Actuación para la Intervención Familiar. Gobierno de Aragón, Departamento de Ciudadanía y Servicios Sociales (IASS). 2016. Available online: http://www.aragon.es/estaticos/GobiernoAragon/Organismos/InstitutoAragonesServiciosSociales/IASS_new/Documentos/infancia/INTERVENCION-FAMILIAR-2016-protocolo.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Gobierno de Aragón. Protocolo para la Prevención y Actuación ante la Mutilación Genital Femenina en Aragón. Instituto Aragonés de la Mujer (IAM). 2016. Available online: http://www.violenciagenero.igualdad.mpr.gob.es/otrasFormas/mutilacion/protocolos/protocolo/pdf/ARAGon2016.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Gobierno de Aragón. Cuaderno Metodológico de Participación Ciudadana nº 1. Dirección General de Participación Ciudadana Acción Exterior y Cooperación (DGPC) del Gobierno de Aragón. 2015. Available online: http://aragonparticipa.aragon.es/sites/default/files/cuaderno_metodologicodef.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer: An Overview. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/health-topics/cancer/who-childhood-cancer-overview-booklet.pdf?sfvrsn=83cf4552_1&download=true (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). World Cancer Report 2014. IARC. 2014. Available online: http://publications.iarc.fr/Non-Series-Publications/World-Cancer-Reports/World-Cancer-Report-2014 (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Instituto Nacional del Cáncer (INC). ¿Qué es el Cáncer? Instituto Nacional del Cáncer. 2015. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/espanol/cancer/naturaleza/que-es (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Kurk, M.E.; Lewis, T.P.; Arsenault, C.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Irimu, G.; Jeong, J.; Lassi, Z.S.; Sawyer, S.M.; Vaivada, T.; Waiswa, P.; et al. Improving health and social systems for all children in LMICs: Structural innovations to deliver high-quality services. Lancet 2022, 399, 1830–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celma Juste, A.J. Psico-Oncología Pediátrica: Valoración e Intervención; Federación Española de Padres de Niños con Cáncer: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo Armentia, A.; Polaino-Lorente, A. El impacto del niño con cáncer en el funcionamiento familiar. Acta Pediatría Española 1999, 57, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Celma Juste, A.J.; Mayoral, B. Guía para padres. Problemática de las Secuelas en el Cáncer Infantil; ASPANOA: Zaragoza, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, G. Encyclopedia of Stress; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.K.; Acquati, C.; Smith, E.; Katerere-Virima, T.; Helbling, L.; Betz, G. The impact of a cancer diagnosis on sibling relationships from childhood through young adulthood: A systematic review. J. Fam. Soc. Work 2020, 23, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrado Val, E. Familias con un hijo con Cáncer: Ajuste, Crianza Parental y Calidad de vida; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2015; Available online: https://idus.us.es/xmlui/handle/11441/33257 (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Jalmsell, L.; Lövgren, M.; Kreicbergs, U.; Henter, J.-I.; Frost, B.-M. Children with cancer share their views: Tell the truth but leave room for hope. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 105, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ituarte Tellaeche, A. Procedimiento y Proceso en Trabajo Social Clínico; Siglo XXI: Madrid, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Society for Social Work Leadership in Health Care (SSWLHC). Standards for Social Work Practice and Staffing in Children´s Hospitals. SSWLHC. 2018. Available online: http://sswlhc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/SSWLHC-Peds-Standards-Final-3.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Du Ranquet, M. Los Modelos en Trabajo Social. Intervención con Personas y Familias; Siglo XXI: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Martínez, M.J. Modelos Teóricos del Trabajo Social; Diego Marín Librero-Editor: Murcia, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente Raneda, M. Cuidar en el cáncer infantil desde el trabajo social. Viure en Salut. 30 Anys Registrant el Cáncer Infantil a la Comunitat Valenciana. January 2017; Volume 108. Available online: http://publicaciones.san.gva.es/publicaciones/documentos/VIURE_EN_SALUT_108.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Vega, V.P.; González, R.; Bustos, J.; Rojo, L.; López, M.E.; Rosas, A.; Hasbún, C.G. Relación entre apoyo en duelo y el síndrome de Burnout en profesionales y técnicos de la salud infantil. Rev. Chil. Pediatr. 2017, 88, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinetta, J.J.; Jankovic, M.; Ben Arush, M.W.; Eden, T.; Epelman, C.; Greenberg, M.L.; Martins, A.G.; Mulhern, R.K.; Oppenheim, D.; Masera, G. Guidelines for the Recognition, Prevention, and Remediation of Burnout in Health Care Professionals Participating in the Care of Children with Cancer: Report of the SIOP Working Committee on Psychosocial Issues in Pediatric Oncology. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 2000, 35, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig Cruells, C. La Supervisión en la Acción Social; Publicacions de la Universitat Rovira i Virgili: Tarragona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, M. SPIKES: A Framework for Breaking Bad News to Patients with Cancer. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2010, 14, 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sector Zaragoza II (Zaragoza Sector II). Hospital Miguel Servet. Servicio Aragonés de Salud (Salud). 2009. Available online: http://sectorzaragozados.salud.aragon.es/paginas-libres/portal-sector/servicios-clinicos/d85a8_servicios-clinicos.html (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Ayarra, M.; Lizarraga, S. Malas noticias y apoyo emocional. ANALES Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2001, 24 (Suppl. S2), 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| In the Patient | In the Family | Common to Both |

|---|---|---|

| Patient’s age and development | Family situation (Description of the family situation, typology, existence of pregnancies, special attention to single parents) | Culture and language, especially for immigrant families |

| Educational status | Siblings: Existence or not and age | Previous experiences and emotions/grief situations |

| Existence of previous disorders or health problems aggravating the disease | Rural environment and/or necessary displacements | Previous experiences of traumatic situations, especially health or lack of resources |

| Intra-family conflicts | Length of hospital stays and prognosis | |

| Socioeconomic/employment/health situation of the family | Personal resources | |

| Extended family: Existence or not and relationship to extended family | Support networks: resources and help from the environment | |

| Caregiver overload and change of roles | Culture and language, especially for immigrant families | |

| Health of family members | ||

| Family situation (Description of the family situation, typology, existence of pregnancies, special attention to single parents) | ||

| Siblings: Existence or not and age | ||

| Intra-family conflicts |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mira-Aladrén, M.; Martín-Peña, J.; Sevillano Cintora, G.; Celma Juste, A.; Gil-Lacruz, M. Childhood Cancer and the Family: A Pilot Proposal for Comprehensive Intervention at the Time of Diagnosis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091790

Mira-Aladrén M, Martín-Peña J, Sevillano Cintora G, Celma Juste A, Gil-Lacruz M. Childhood Cancer and the Family: A Pilot Proposal for Comprehensive Intervention at the Time of Diagnosis. Healthcare. 2022; 10(9):1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091790

Chicago/Turabian StyleMira-Aladrén, Marta, Javier Martín-Peña, Gemma Sevillano Cintora, Antonio Celma Juste, and Marta Gil-Lacruz. 2022. "Childhood Cancer and the Family: A Pilot Proposal for Comprehensive Intervention at the Time of Diagnosis" Healthcare 10, no. 9: 1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091790

APA StyleMira-Aladrén, M., Martín-Peña, J., Sevillano Cintora, G., Celma Juste, A., & Gil-Lacruz, M. (2022). Childhood Cancer and the Family: A Pilot Proposal for Comprehensive Intervention at the Time of Diagnosis. Healthcare, 10(9), 1790. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091790