A Pilot Study Conducting Online Think Aloud Qualitative Method during Social Distancing: Benefits and Challenges

Abstract

:1. Introduction

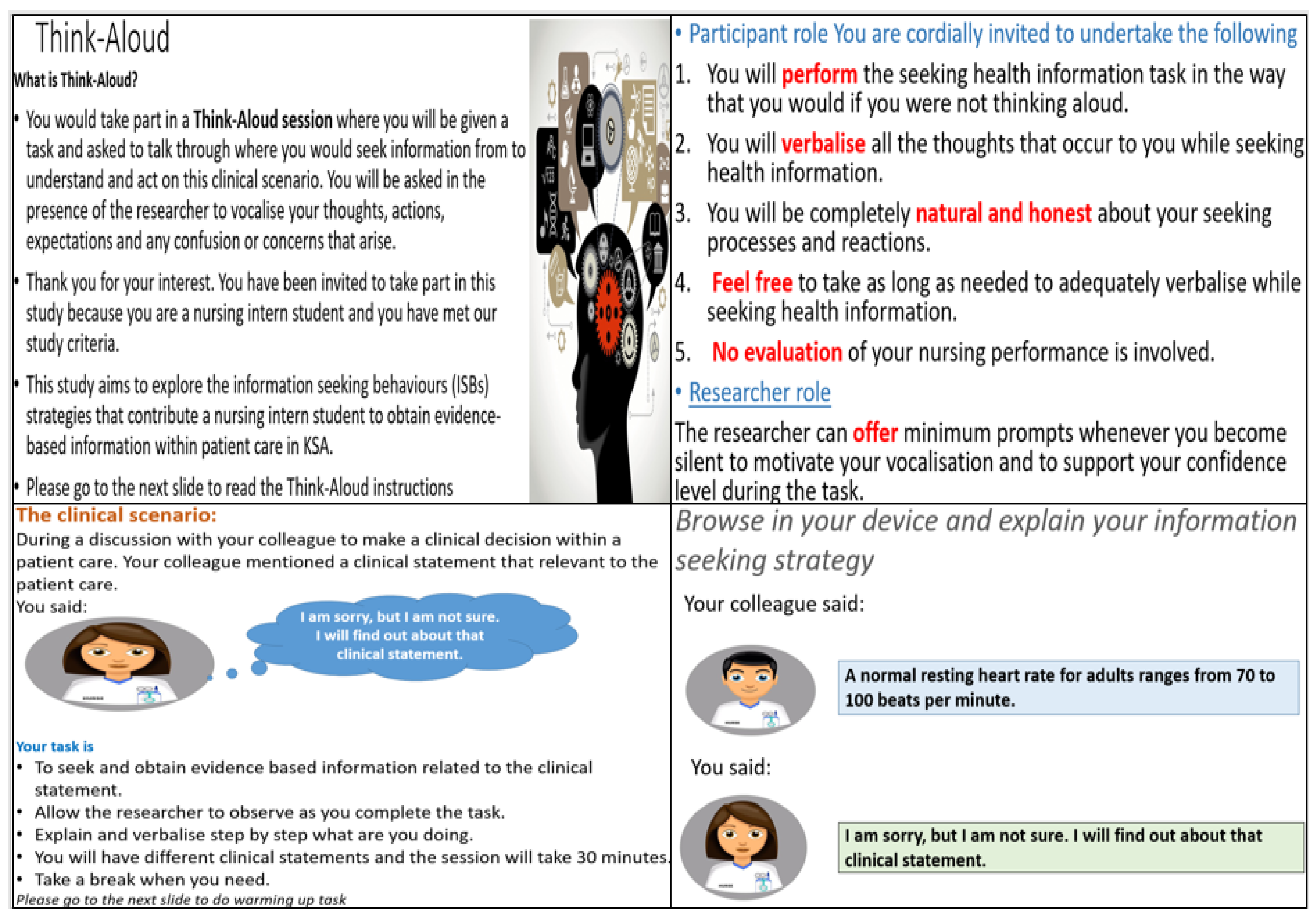

1.1. Think Aloud (TA)

1.2. Moving to Online Methods

- To illustrate how TA could be conducted online and evaluate transferring the approach online;

- To consider the benefits and challenges of remote data collection in a TA study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Recruitment

2.3. Ethics

2.4. Methodological Modifications to the Traditional TA

2.5. Evaluation of the Online TA Method

3. Results

3.1. Recruitment

P3: I do not know how to use Microsoft Teams in this task. Could you teach me?

Researcher: I will share my screen and explain to you how to use it.

Researcher: Which device do you use to enter Teams?

P6: Hi! I am using my smartphone?

Researcher: Sorry, can you use a laptop to enter? Because it is necessary to participate in this study, due to the nature of the Think Aloud session.

P6: I do not have a laptop right now.

Researcher: Sorry, I have to rearrange this session for another time, thank you for your willingness to participate.

3.2. Rapport

Participant: [Silent for 40 s]

Researcher: Keep on talking…

Participant: I will thanks.[P2]

Participant: [Call disrupted for 20 s]

Researcher: Hi! I cannot hear you?

Researcher: How are you?! [Connection back]

Participant: I’m good thanks.

Researcher: Can you complete sharing screen and resume again?

Participant: I can... yes, It’s fine.[P4]

3.3. Ethical Concerns

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dodds, S.; Hess, A.C. Adapting research methodology during COVID-19: Lessons for transformative service research. J. Serv. Manag. 2020, 32, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.S.; Wharrad, H.; Moffatt, F.; Taylor, M.; Ladan, M. Q Methodology in the COVID-19 Era. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, M.; Gibson, W.; Hall, A.; Richards, D.; Callery, P. Online vs. face-to-face discussion in a web-based research methods course for postgraduate nursing students: A quasi-experimental study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atherton, H.; Fleming, J.; Williams, V.; Powell, J. Online patient feedback: A cross-sectional survey of the attitudes and experiences of United Kingdom health care professionals. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2019, 24, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cater, J.K. Skype a cost-effective method for qualitative research. Rehabil. Couns. Educ. J. 2011, 4, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Almost, J.; Gifford, W.A.; Doran, D.; Ogilvie, L.; Miller, C.; Rose, D.N.; Squires, M.; Carryer, J.; McShane, J.; Miller, K. The Acceptability and Feasibility of Implementing an Online Educational Intervention With Nurses in a Provincial Prison Context. J. Forensic Nurs. 2019, 15, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.R. Skype: An appropriate method of data collection for qualitative interviews? Hilltop Rev. 2012, 6, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Woodyatt, C.R.; Finneran, C.A.; Stephenson, R. In-person versus online focus group discussions: A comparative analysis of data quality. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.R.; Scheitle, C.P.; Ecklund, E.H. Beyond the in-person interview? How interview quality varies across in-person, telephone, and Skype interviews. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2019, 39, 1142–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Iacono, V.; Symonds, P.; Brown, D.H. Skype as a tool for qualitative research interviews. Sociol. Res. Online 2016, 21, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, M.M.; Ambagtsheer, R.C.; Casey, M.G.; Lawless, M. Using zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: Perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1609406919874596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, M.W.; Steen, T.; Van Den Bos, C.; Geenen, M. The think aloud method: A guide to user interface design. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2004, 73, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jääskeläinen, R. Think-aloud protocol. Handb. Transl. Stud. 2010, 1, 371–374. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.J.; Zhang, D. Think-aloud protocols. In The Routledge Handbook of Research Methods in Applied Linguistics; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 302–311. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel Latif, M.M. Using think-aloud protocols and interviews in investigating writers’ composing processes: Combining concurrent and retrospective data. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2019, 42, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenwald, D.H.; Wildemuth, B.; Harmon, G.L. A research method to investigate information seeking using the concept of information horizons: An example from a study of lower socio-economic students’ information seeking behavior. New Rev. Inf. Behav. Res. 2001, 2, 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey, U.; Acton, T.; Conboy, K. Concurrent and retrospective think-aloud protocols for information systems research. In Proceedings of the Bled eConference, Bled, Slovenia, 17–20 June 2012; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Wolcott, M.D.; Lobczowski, N.G. Using cognitive interviews and think-aloud protocols to understand thought processes. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2021, 13, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, D.W.; Arsal, G. The think aloud method: What is it and how do I use it? Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2017, 9, 514–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Simon, H.A. Protocol analysis. A Companion Cogn. Sci. 1998, 14, 425–432. [Google Scholar]

- Leighton, J.P. Using Think-Aloud Interviews and Cognitive Labs in Educational Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Whalley, J.; Kasto, N. A qualitative think-aloud study of novice programmers’ code writing strategies. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Innovation & Technology in Computer Science Education, Uppsala, Sweden, 23–25 June 2014; pp. 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen, H.M.; Slettebø, Å.; Fossum, M. Registered nurses’ clinical reasoning in home healthcare clinical practice: A think-aloud study with protocol analysis. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 40, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleberry, A.; Nolen, A. Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: Is it as easy as it sounds? Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- In, J. Introduction of a pilot study. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2017, 70, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshammari, T.; Alhadreti, O.; Mayhew, P. When to ask participants to think aloud: A comparative study of concurrent and retrospective think-aloud methods. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2015, 6, 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Razali, Z.; Kader, M.; Affendi, N.; Daud, M. Think-aloud Technique in Assessing Practical Experience: A Pilot Study. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 10–13 September 2020; p. 012084. [Google Scholar]

- Joe, J.; Chaudhuri, S.; Le, T.; Thompson, H.; Demiris, G. The use of think-aloud and instant data analysis in evaluation research: Exemplar and lessons learned. J. Biomed. Inform. 2015, 56, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leech, N.L.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. An array of qualitative data analysis tools: A call for data analysis triangulation. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2007, 22, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, W. Data Collection: Key Debates and Methods in Social Research; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Markham, A.N.; Tiidenberg, K.; Herman, A. Ethics as methods: Doing ethics in the era of big data research—introduction. Soc. Media+ Soc. 2018, 4, 2056305118784502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Facca, D.; Smith, M.J.; Shelley, J.; Lizotte, D.; Donelle, L. Exploring the ethical issues in research using digital data collection strategies with minors: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelinas, L.; Pierce, R.; Winkler, S.; Cohen, I.G.; Lynch, H.F.; Bierer, B.E. Using social media as a research recruitment tool: Ethical issues and recommendations. Am. J. Bioeth. 2017, 17, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deakin, H.; Wakefield, K. Skype interviewing: Reflections of two PhD researchers. Qual. Res. 2014, 14, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janghorban, R.; Roudsari, R.L.; Taghipour, A. Skype interviewing: The new generation of online synchronous interview in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2014, 9, 24152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, F.E.; Morris, M.; Rumsey, N. Doing synchronous online focus groups with young people: Methodological reflections. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Bawab, N.; De Mooij, J.; Sutter Widmer, D.; Szilas, N.; De Vriese, C.; Bugnon, O. An open randomized controlled study comparing an online text-based scenario and a serious game by Belgian and Swiss pharmacy students. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.L.; McKeever, P.; Coyte, P.C. Recruitment issues in healthcare research: The situation in home care. Health Soc. Care Community 2003, 11, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe-Galloway, S.; Madison, L.; Watkins, K.L.; Nguyen, A.T.; Chen, L.-W. Recruitment and retention of mental health care providers in rural Nebraska: Perceptions of providers and administrators. Rural. Remote Health 2015, 15, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, A.-F.; Saunders, C.S. Emotional and Cognitive Overload: The Dark Side of Information Technology; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Frisby, B.N.; Martin, M.M. Instructor–student and student–student rapport in the classroom. Commun. Educ. 2010, 59, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansen, H.M. Researcher positionality in participant observation with preschool age children: Challenges and strategies for establishing rapport with teachers and children simultaneously. In Researching Children and Youth: Methodological Issues, Strategies, and Innovations; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bonner, A.; Tolhurst, G. Insider-outsider perspectives of participant observation. Nurse Res. (Through 2013) 2002, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.C.; Worth, A. The use of the telephone interview for research. NT Res. 2001, 6, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, P.; Stewart, K.; Treasure, E.; Chadwick, B. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 204, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewson, C.; Vogel, C.; Laurent, D. Internet research methods; Wiley StatsRef Stat. Ref. Online: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Seitz, S. Pixilated partnerships, overcoming obstacles in qualitative interviews via Skype: A research note. Qual. Res. 2016, 16, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J. Conducting research interviews. Manag. Res. Rev. 2012, 35, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, N. Using email interviews in qualitative educational research: Creating space to think and time to talk. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2016, 29, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbe, A.; Brandon, S.E. Building and maintaining rapport in investigative interviews. Police Pract. Res. 2014, 15, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratch, J.; Okhmatovskaia, A.; Lamothe, F.; Marsella, S.; Morales, M.; van der Werf, R.J.; Morency, L.-P. Virtual rapport. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Intelligent Virtual Agents, Marina Del Rey, CA, USA, 21–23 August 2006; pp. 14–27. [Google Scholar]

| How easy was it to participate in the online TA session? |

| How difficult was it to participate in the online TA session? |

| Do you think that doing a TA session online encouraged you to participate in the research? |

| Do you have any general comments about the online session? |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alhejaili, A.; Wharrad, H.; Windle, R. A Pilot Study Conducting Online Think Aloud Qualitative Method during Social Distancing: Benefits and Challenges. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1700. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091700

Alhejaili A, Wharrad H, Windle R. A Pilot Study Conducting Online Think Aloud Qualitative Method during Social Distancing: Benefits and Challenges. Healthcare. 2022; 10(9):1700. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091700

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhejaili, Asim, Heather Wharrad, and Richard Windle. 2022. "A Pilot Study Conducting Online Think Aloud Qualitative Method during Social Distancing: Benefits and Challenges" Healthcare 10, no. 9: 1700. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091700

APA StyleAlhejaili, A., Wharrad, H., & Windle, R. (2022). A Pilot Study Conducting Online Think Aloud Qualitative Method during Social Distancing: Benefits and Challenges. Healthcare, 10(9), 1700. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091700