Illness Perceptions and Self-Management among People with Chronic Lung Disease and Healthcare Professionals: A Mixed-Method Study Identifying the Local Context

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Settings and Participants

2.3. Measurements and Outcomes

2.3.1. Qualitative Interview

2.3.2. Quantitative Survey

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Validity and Reliability

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Theme 1: Illness Perception

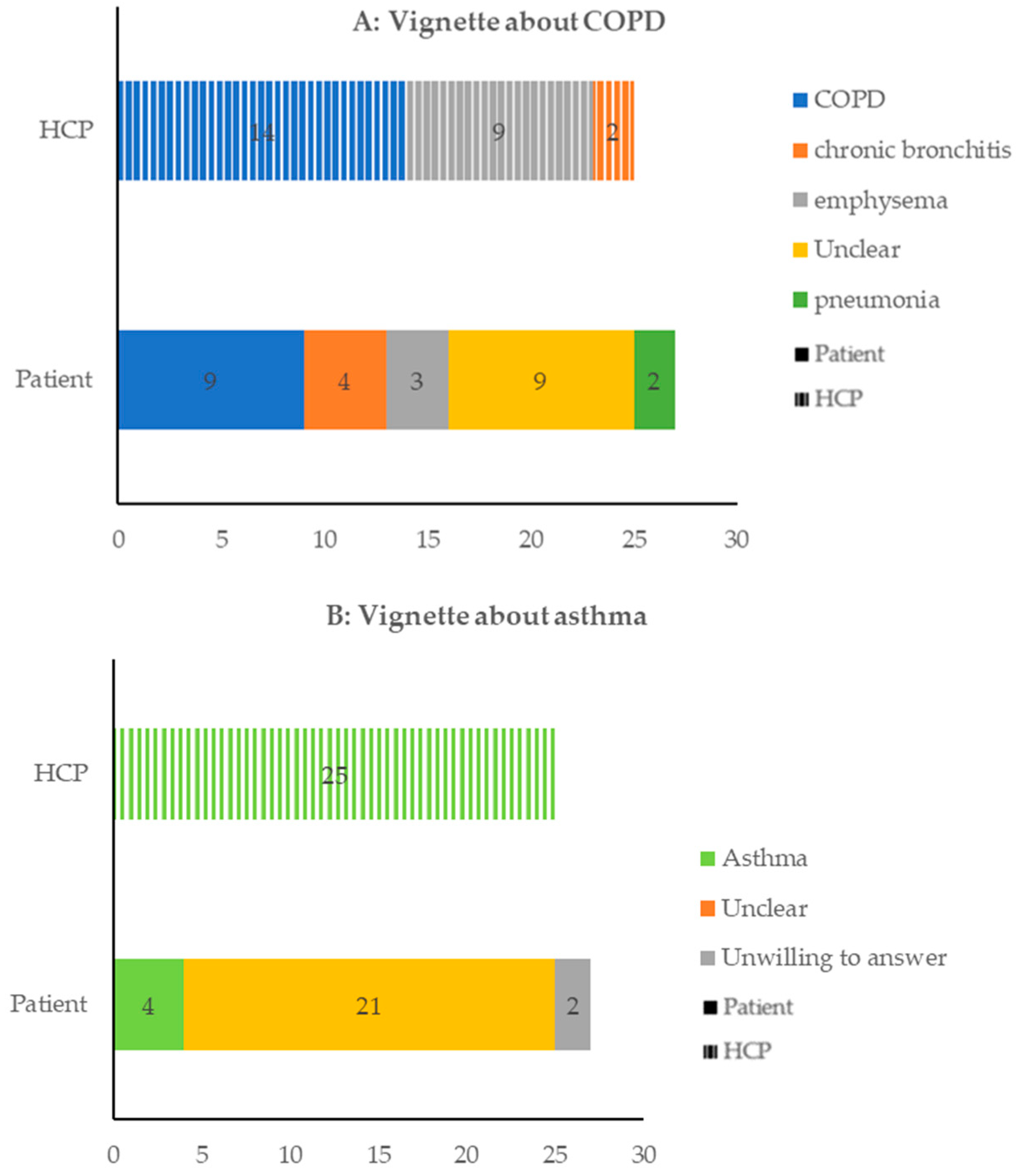

3.2.1. Theme 1a: Coherence and Identification

3.2.2. Theme1b: Perceived Causes

3.2.3. Theme 1c: Perceived Consequences and Emotional Response

3.2.4. Theme 1d: Curable Possibility and Perceived Duration

3.2.5. Theme1e: Identified Disease Control

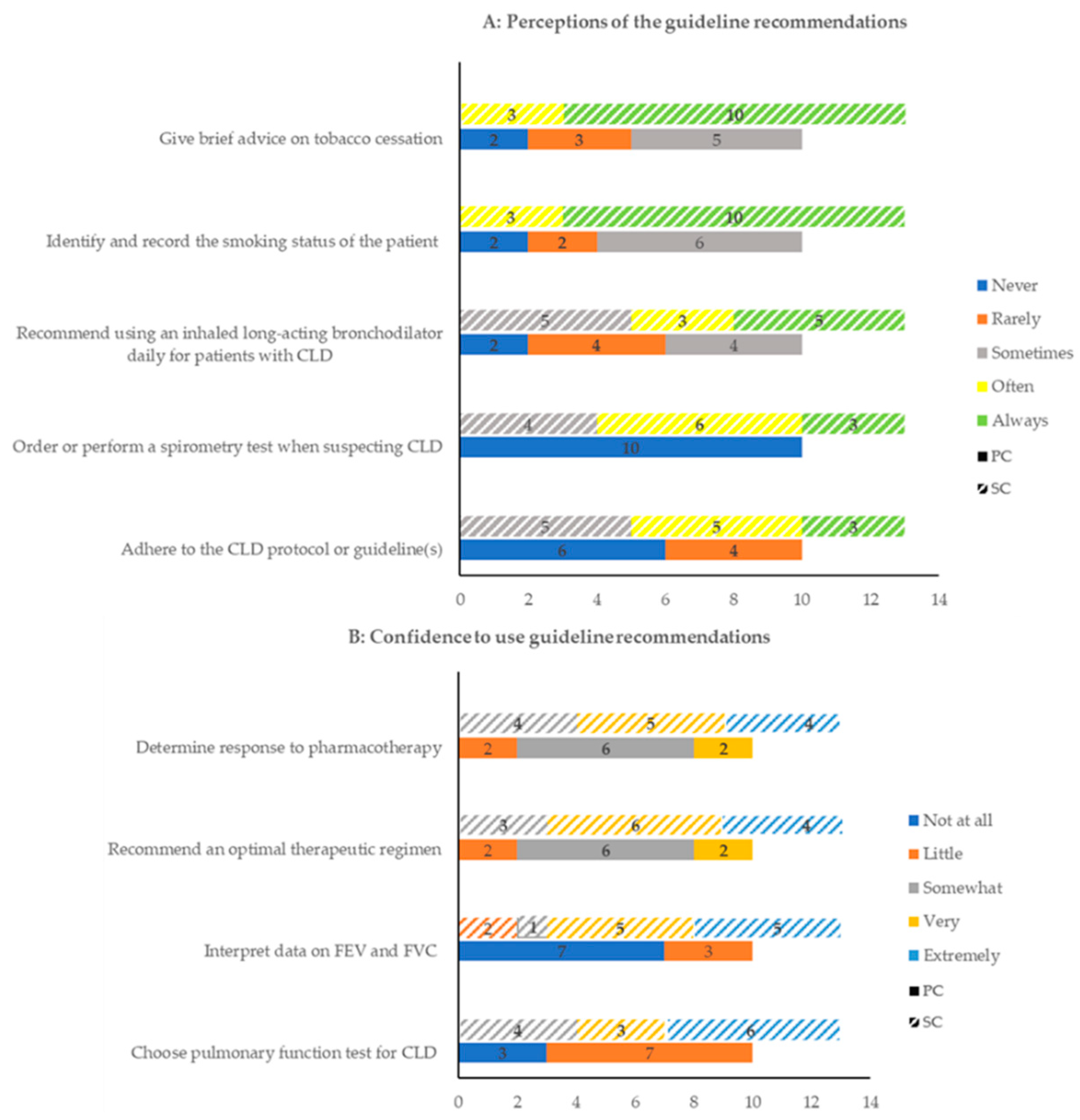

3.3. Theme 2: Identified SM Skills

3.4. Theme 3: Factors Influencing SM Skills

3.5. Theme 4: Needs for SM

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, K.W.; Yang, T.; Xu, J.Y.; Yang, L.; Zhao, J.P.; Zhang, X.Y.; Bai, C.X.; Kang, J.; Ran, P.X.; Shen, H.H.; et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of asthma in China: A national cross-sectional study. Lancet 2019, 394, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, J.Y.; Yang, L.; Xu, Y.J.; Zhang, X.Y.; Bai, C.X.; Kang, J.; Ran, P.X.; Shen, H.H.; Wen, F.Q.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China (the China Pulmonary Health CPH study): A national cross-sectional study. Lancet 2018, 391, 1706–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, F.; Gibson, P.G.; Guo, M.; Zhang, W.J.; Gao, P.; Zhang, H.P.; Harvey, E.S.; Li, H.; Zhang, J. Severe and uncontrolled asthma in China: A cross-sectional survey from the Australasian Severe Asthma Network. J. Thorac. Dis. Dis. 2017, 9, 1333–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.F.; Wang, Y.F.; Ming, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L.Y. Disease burden of COPD in China: A systematic review. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2018, 13, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.Y.; Hallensleben, C.; Zhang, W.H.; Jiang, Z.L.; Shen, H.X.; Gobbens, R.J.J.; Van der Kleij, R.; Chavannes, N.H.; Versluis, A. Blended Self-Management Interventions to Reduce Disease Burden in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Asthma: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.R.; Holman, H.R. Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2003, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavord, I.D.; Jones, P.W.; Burgel, P.R.; Rabe, K.F. Exacerbations of COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2016, 11, 21–30. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.T.; Xing, B.; Tang, H.P.; Yang, L.; Yuan, Y.D.; Gu, Y.H.; Chen, P.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.G.; et al. Hospitalization Due to Asthma Exacerbation: A China Asthma Research Network (CARN) Retrospective Study in 29 Provinces Across Mainland China. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2020, 12, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallensleben, C.; Meijer, E.; Biewenga, J.; Kievits-Smeets, R.M.M.; Veltman, M.; Song, X.; van Boven, J.F.M.; Chavannes, N.H. Reducing Delay through edUcation on eXacerbations (REDUX) in patients with COPD: A pilot study. Clin. eHealth 2020, 3, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakema, E.A.; van der Kleij, R.; Poot, C.C.; Le An, P.; Anastasaki, M.; Crone, M.R.; Hong, L.; Kirenga, B.; Lionis, C.; Mademilov, M.; et al. Mapping low-resource contexts to prepare for lung health interventions in four countries (FRESH AIR): A mixed-method study. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, E57–E70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.S.L.; Abdullah, N.; Abdullah, A.; Liew, S.M.; Ching, S.M.; Khoo, E.M.; Jiwa, M.; Chia, Y.C. Unmet needs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): A qualitative study on patients and doctors. BMC Fam. Pract. 2014, 15, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daivadanam, M.; Ingram, M.; Sidney Annerstedt, K.; Parker, G.; Bobrow, K.; Dolovich, L.; Gould, G.; Riddell, M.; Vedanthan, R.; Webster, J.; et al. The role of context in implementation research for non-communicable diseases: Answering the ‘how-to’ dilemma. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214454. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, E.; Corte, C.; Steffen, A.; DeVon, H.A.; Collins, E.G.; McCabe, P.J. Illness Representation and Self-Care Ability in Older Adults with Chronic Disease. Geriatrics 2018, 3, 45. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventhal, H.M.D.; Meyer, D.; Nerenz, D. The common sense representation of illness danger. Med. Psychol. 1980, 2, 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Achstetter, L.I.; Schultz, K.; Faller, H.; Schuler, M. Leventhal’s common-sense model and asthma control: Do illness representations predict success of an asthma rehabilitation? J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 327–336. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandelowski, M. Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed-method studies. Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 246–255. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, H.K.; Park, S.W.; Park, J.W.; Choi, H.S.; Kim, T.H.; Yoon, H.K.; Yoo, K.H.; Jung, K.S.; Kim, D.K. Chronic cough as a novel phenotype of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2018, 13, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusch, P.I.; Ness, L.R. Are We There Yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, E.; Petrie, K.J.; Main, J.; Weinman, J. The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire. J. Psychosom. Res. 2006, 60, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chiu, K.; Wang, T.J. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the brief illness perception questionnaire for patients with coronary heart disease. J. Orient. Inst. Technol. 2011, 2, 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, E.; Gebhardt, W.A.; Dijkstra, A.; Willemsen, M.C.; Van Laar, C. Quitting smoking: The importance of non-smoker identity in predicting smoking behaviour and responses to a smoking ban. Psychol. Health 2015, 30, 1387–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, E.; Van den Putte, B.; Gebhardt, W.A.; Van Laar, C.; Bakk, Z.; Dijkstra, A.; Fong, G.T.; West, R.; Willemsen, M.C. A longitudinal study into the reciprocal effects of identities and smoking behaviour: Findings from the. ITC Netherlands Survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 200, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas, G.D.; Williamson, J.C.; Kalhan, R.; Thomashow, B.; Scheckermann, J.L.; Walsh, J.; Abdolrasulnia, M.; Foster, J.A. Barriers to adherence to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease guidelines by primary care physicians. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2011, 6, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Wang, H.J.; Du, L.Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.J.; Zhang, R.M. Disease knowledge and self-management behavior of COPD patients in China. Medicine 2019, 98, e14460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.Y.; Tian, Q.; Chen, T.T.; Ye, Y.S.; Lin, Q.X.; Han, D.; Ou, C.Q. Temperature Variability and Hospital Admissions for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Analysis of Attributable Disease Burden and Vulnerable Subpopulation. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2020, 15, 2225–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieson, A.; Grande, G.; Luker, K. Strategies, facilitators and barriers to implementation of evidence-based practice in community nursing: A systematic mixed-studies review and qualitative synthesis. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2019, 20, e6. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Feng, Z.C.; Dong, Z.X.; Li, W.P.; Chen, C.Y.; Gu, Z.C.; Wei, A.H.; Feng, D. Does Having a Usual Primary Care Provider Reduce Polypharmacy Behaviors of Patients With Chronic Disease? A Retrospective Study in Hubei Province, China. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 802097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, J.B.; Kendrick, P.J.; Paulson, K.R.; Gupta, V.; Vos, T.; GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhong, L.; Yuan, S.; van de Klundert, J. Why patients prefer high-level healthcare facilities: A qualitative study using focus groups in rural and urban China. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000854. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, J.R.; Buist, A.S.; Gaga, M.; Gianella, G.E.; Kirenga, B.; Khoo, E.M.; Mendes, R.G.; Mohan, A.; Mortimer, K.; Rylance, S.; et al. Challenges in the Implementation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Guidelines in Low- and Middle-Income Countries An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021, 18, 1269–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurgeirsdottir, J.; Halldorsdottir, S.; Arnardottir, R.H.; Gudmundsson, G.; Bjornsson, E.H. Frustrated Caring: Family Members’ Experience of Motivating COPD Patients Towards Self-Management. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2020, 15, 2953–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Surani, S.; McGuinness, S.; Eudicone, J.; Gilbert, I.; Subramanian, S. Current practice patterns, challenges, and educational needs of asthma care providers in the United States. J. Asthma 2021, 58, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Duan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; He, Y.; Li, W.; Jin, W. Impacts of government supervision on hospitalization costs for inpatients with COPD: An interrupted time series study. Medicine 2020, 99, e18977. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | A Higher Score Implies: |

|---|---|

| Consequences | Greater perceived influence of the illness |

| Timeline | A stronger belief in a chronic time course |

| Personal control | Greater perceived personal control |

| Treatment control | Greater perceived control of the treatment |

| Identity | Greater experience of severe symptoms as a result of the illness |

| Concern | Greater feelings of concern about illness |

| Coherence | A better understanding of the illness |

| Emotion | A stronger emotional response to the illness |

| Data about Patients | N | Data about HCPs | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Location | ||

| Primary care | 14 | Primary care | 13 |

| Secondary care | 11 | Secondary care | 10 |

| Disease diagnosis | Gender | ||

| COPD | 18 | Male | 4 |

| Emphysema | 3 | Female | 19 |

| Asthma | 2 | Years of working experience | |

| Chronic bronchitis | 2 | <5 | 2 |

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 69.60 ± 13.07 | 5–10 | 19 |

| Years with disease | ≥10 | 2 | |

| <5 | 5 | ||

| 5–10 | 7 | ||

| ≥10 | 13 | ||

| Number of exacerbations in the last year | |||

| 0 | 2 | ||

| 1 | 10 | ||

| ≥2 | 13 | ||

| Smoking status | |||

| Current smokers | 5 | ||

| Ex-smokers | 16 | ||

| Never smoked | 4 | ||

| Mean years of smoking | |||

| Current smokers | 33.75 ± 14.24 | ||

| Ex-smokers | 48.80 ± 13.07 | ||

| Data about Patients | N |

|---|---|

| Current smokers’ cigarette situation | |

| Mean daily smoking (cigarettes) | 9.40 ± 3.78 |

| Duration of quitting smoking (months) | |

| <6 | 2 |

| 6–12 | 3 |

| ≥12 | 0 |

| Frequency of quitting smoking | |

| <2 | 1 |

| ≥2 | 4 |

| Interest in quitting smoking | |

| Not at all | 1 |

| A little | 1 |

| Somewhat | 2 |

| Much | 0 |

| Very much | 1 |

| Domains | Patients (n = 25) | HCPs (n = 23) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC (n = 14) | SC (n = 11) | Total (n = 25) | PC (n = 10) | SC (n = 13) | Total (n = 23) | |

| Consequences | 5.21 ± 0.80 | 5.91 ± 0.94 | 5.52 ± 0.92 | 5.90 ± 0.74 *b | 4.46 ± 0.97 | 5.09 ± 1.12 |

| Timeline | 8.07 ± 2.53 | 9.18 ± 0.40 | 8.56 ± 1.96 | 9.40 ± 0.52 | 9.08 ± 0.49 | 9.22 ± 0.52 |

| Personal control | 5.29 ± 0.61 | 5.45 ± 0.69 | 5.36 ± 0.64 | 4.10 ± 0.88 *b | 3.38 ± 0.51 | 3.70 ± 0.76 **c |

| Treatment control | 6.71 ± 1.07 | 7.36 ± 1.21 | 7.00 ± 1.15 | 2.60 ± 0.52 | 3.08 ± 0.64 | 2.87 ± 0.63 **c |

| Coherence | 6.64 ± 0.84 | 7.19 ± 0.75 | 6.88 ± 0.83 | 5.30 ± 1.42 *b | 6.39 ± 1.04 | 5.91 ± 1.31 **c |

| Concern | 7.27 ± 1.10 | 7.36 ± 0.93 | 7.32 ± 0.99 | 5.60 ± 1.17 **b | 2.92 ± 0.28 | 4.09 ± 1.56 **c |

| Identity | 6.27 ± 0.79 | 5.79 ± 0.80 | 6.00 ± 0.82 | 5.60 ± 0.52 | 5.77 ± 0.73 | 5.70 ± 0.63 |

| Emotional response | 7.45 ± 0.69 | 8.21 ± 0.80 *a | 7.88 ± 0.83 | 4.54 ± 1.51 *b | 3.30 ± 0.48 | 4.00 ± 1.31 **c |

| Total score | 53.29 ± 3.99 | 56.09 ± 3.05 | 54.42 ± 3.81 | 41.80 ± 2.57 *b | 39.62 ± 1.39 | 40.57 ± 2.23 **c |

| Data From Patient | Data from Healthcare Professionals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quotes | Category | Theme | Category | Quotes |

| Q1: “It felt like a plastic bag on my face, and I could not breathe in the oxygen at that moment.” (Patient 15, SC). | Illness coherence | 1a. Illness coherence and identification | Illness coherence | Q2: “It is easy to diagnose it from my experience.” (HCP1, PC) |

| Q3: “We always recommend that patients have a spirometry test.” (HCP 14, SC) | ||||

| Q4: “Eating fried sunflower triggered my episode.” (Patient 2, PC) | Illness disease | 1b. perceived causes | Disease cause | Q6: “Air pollution is the most important reason.” (HCP 23, SC) |

| Q5: “When I moved the goods, I was out of breath and fainted.” (Patient 15, SC) | ||||

| Q7: “I used to participate in square dancing.” (Patient 4, PC) Q8: “When I cough in public, people cover their mouths with their hands and go away from me. Their actions depress me.” (Patient 19, SC) | Reduced social interaction | 1c. perceived consequences and emotional response | Physical limitation | Q10: “Patients work less after the exacerbation due to decreased physical function.” (HCP1, PC) |

| Decreased lung function | Q11: “A new exacerbation accounts for the decreased lung function.” (HCP10, PC) | |||

| Q9: “I can’t work now. I am like a burden to my family.” (Patient 16, SC) | Indifference on patient complains | Q12: “I do not have time to explore patients’ feelings.” (HCP6, SC) | ||

| Q13: “No episodes disturb my daily life. I am just as healthy as those who do not have COPD or other chronic diseases.” (Patient 17, SC) | Asymptomatic equal to cured | 1d. curable possibility and perceived duration | Incurable and chronic | Q14: “Chronic lung disease will accompany the patients for a lifetime.” (HCP6, PC) Q15: “It could not be cured.” (HCP16, SC) |

| Q16: “I cannot manage the disease by myself.” (Patient 7, PC) | Poor self-management | 1e. identified disease control | Poor patient self-management | Q18: “SM is helpful to control the disease, but few patients can make it due to limited disease knowledge.” (HCP17, SC) |

| Q17: “Doctors are the professionals. I do what they asked me to do.” (Patient 20, SC) | Passive role with doctors | Guideline use in practice | Q19: “Patients’ symptoms were more complicated than described in the guidelines.” (HCP19, SC) Q20: “Few of us know the guidelines.” (HCP9, PC) | |

| Q21: “Well, when I had the early symptoms, I thought I had a cold.” (Patient 8, PC) | Late exacerbation recognition | 2. identified SM skills | Patient delayed action | Q25: “Some patients do not visit us until their family members force them.” (HCP10, PC) Q26: “Patients did not contact us until they reached a crisis point leading to hospitalization.” Q27: “He sends a message or dials a voice call to me via Wechat when he feels uncomfortable.” (HCP16, SC) |

| Q23: “If my symptoms worsen, I will ask my daughter to contact my doctor immediately.” (Patient 13, PC) Q24: “Early action can reduce the risk of being sent to the hospital.” (Patient 14, PC) | Early exacerbation action | Patient prompt action | ||

| Themes & Category | Explanation | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Generic factors influencing SM skills | ||

| Disease knowledge | Sufficient knowledge facilitated patients to develop SM skills, while insufficient knowledge was the barrier. | Q28: “I know nothing about the disease or the episode so that I could do nothing about it.” (Patient 2, PC) Q29: “My knowledge of the disease helps a lot.” (Patient 13, PC) |

| Former experience with exacerbations | Realizing the importance of early detection and prompt action from past experiences were the facilitators. Habituation to the disease from the former experience was the barrier. | Q30: “After my previous painful experience in the hospital, I realized that attention to the different symptoms (exacerbation) and visiting doctors early was essential.” (Patient 15, SC) Q31: “…However, I frequently did nothing about the worsening symptoms because I learned to live with it.” (Patient 16, SC) |

| Specific factors influencing the exacerbation recognition | ||

| Family support | Helpful family support was the facilitator. In contrast, insufficient family support when patients were at home was the barrier. | Q32: “My daughters sent me to the hospital and covered the diagnosis cost. Their actions are warm and helpful.” (Patient 14, PC) Q33: “Family members regarded patients as well-functioned labor and expected them to do higher intensity household chores than the patient could endure. Such patients went on with the housework with all exacerbations.” (HCP 23, SC) |

| Perceived illness severity | Perceiving the exacerbation as usual was a barrier. The perception that the exacerbation was a hazardous event facilitated recognizing exacerbations early. | Q34: “I must pay attention to my disease carefully. Otherwise, I will be published by the worsened exacerbations.” (Patient 23, SC) Q35: “Some patients would not think breathlessness or coughing was a problem unless these symptoms disturb their eating and drinking.” (HCP 23, SC) |

| Self-empowerment | High self-empowerment facilitated the patients’ act on the exacerbations and vice versa. | Q36: “For the early symptoms, I can control them myself effectively. I will contact my daughter for the ambulance for symptoms out of my control.” (Patient 13, PC) Q37: “I always try to avoid the medicine or the doctors, even if I know my symptoms get worse.” (Patient 14, PC) |

| Chinese herb | Patients perceived the Chinese herb as facilitators, while HCPs perceived patients should take these medications with their suggestions. | Q38: “Chinese herb relieved aggravation.” (Patient 4, PC) Q39: “Patients take the Chinese herbs by themselves without informing us. To make sure the medicine works well, they should ask our advice before taking unprescribed Chinese medicine from us.” (Patient 5, PC) |

| Medical ex-penditure af-fordability | The higher medical expenditure affordability, the more likely the patient is to see a doctor early. | Q40: “Visiting the doctors means paying money, which is the last thing I want to do.” (Patient 4, PC) Q41: “My retirement pension and medical insurance can cover all the medical costs. When I am uncomfortable, I just visit the doctors.” (Patient 12, PC) |

| Categories | Explanation | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Increased disease knowledge | Q42: “The doctor told me I was diagnosed with COPD and left…I expected to know more about this disease.” (Patient 15, SC) Q43: “With more information on disease and medications, patients will be more familiar with the seriousness of their condition, manage risk factors and change behavior, and then take action to meet their own needs for disease management.” (HCP 23, SC) | |

| Individualized SM plan | Q44: “I need one intervention to help me recognize the episode early and act on it early.” (Patient 10, PC) | |

| Nurse specialist | Q45: “A nurse specialist experienced in dealing with patients will be helpful to deliver SM information.” (HCP 17, SC) | |

| eHealth use | Q46: “eHealth will help us deliver SM information to patients, e.g., Wechat.” (HCP 21, SC) | |

| Q47: “If we could remotely monitor patients’ diseases, we could provide more care to more patients.” (HCP 21, SC) | ||

| Sufficient family support | Q48: “When I forgot to take medicine, my family members remaindered me about it immediately. Family support can help me a lot.” (Patient 10, PC) | |

| Policy support | Q49: “With the economic policy support from the government, we will have more resources to provide SM.” (HCP 2, PC) | |

| Q50: “If public medical insurance can cover more medical costs, more patients will choose to visit the doctors earlier.” (HCP 22, SC) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, X.; Hallensleben, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, Z.; Shen, H.; Gobbens, R.J.J.; Chavannes, N.H.; Versluis, A. Illness Perceptions and Self-Management among People with Chronic Lung Disease and Healthcare Professionals: A Mixed-Method Study Identifying the Local Context. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1657. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091657

Song X, Hallensleben C, Li B, Zhang W, Jiang Z, Shen H, Gobbens RJJ, Chavannes NH, Versluis A. Illness Perceptions and Self-Management among People with Chronic Lung Disease and Healthcare Professionals: A Mixed-Method Study Identifying the Local Context. Healthcare. 2022; 10(9):1657. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091657

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Xiaoyue, Cynthia Hallensleben, Bo Li, Weihong Zhang, Zongliang Jiang, Hongxia Shen, Robbert J. J. Gobbens, Niels H. Chavannes, and Anke Versluis. 2022. "Illness Perceptions and Self-Management among People with Chronic Lung Disease and Healthcare Professionals: A Mixed-Method Study Identifying the Local Context" Healthcare 10, no. 9: 1657. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091657

APA StyleSong, X., Hallensleben, C., Li, B., Zhang, W., Jiang, Z., Shen, H., Gobbens, R. J. J., Chavannes, N. H., & Versluis, A. (2022). Illness Perceptions and Self-Management among People with Chronic Lung Disease and Healthcare Professionals: A Mixed-Method Study Identifying the Local Context. Healthcare, 10(9), 1657. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091657