Mental Health Support for Hospital Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Characteristics of the Services and Feedback from the Providers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.1.1. Identification of Centres Where Mental Health Support Services Were Provided

2.1.2. Contact with the Chiefs of the Identified Mental Health Support Services

2.1.3. Contact with the Individual Staff Members Providing the Mental Health Support

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data and Analysis

3. Results

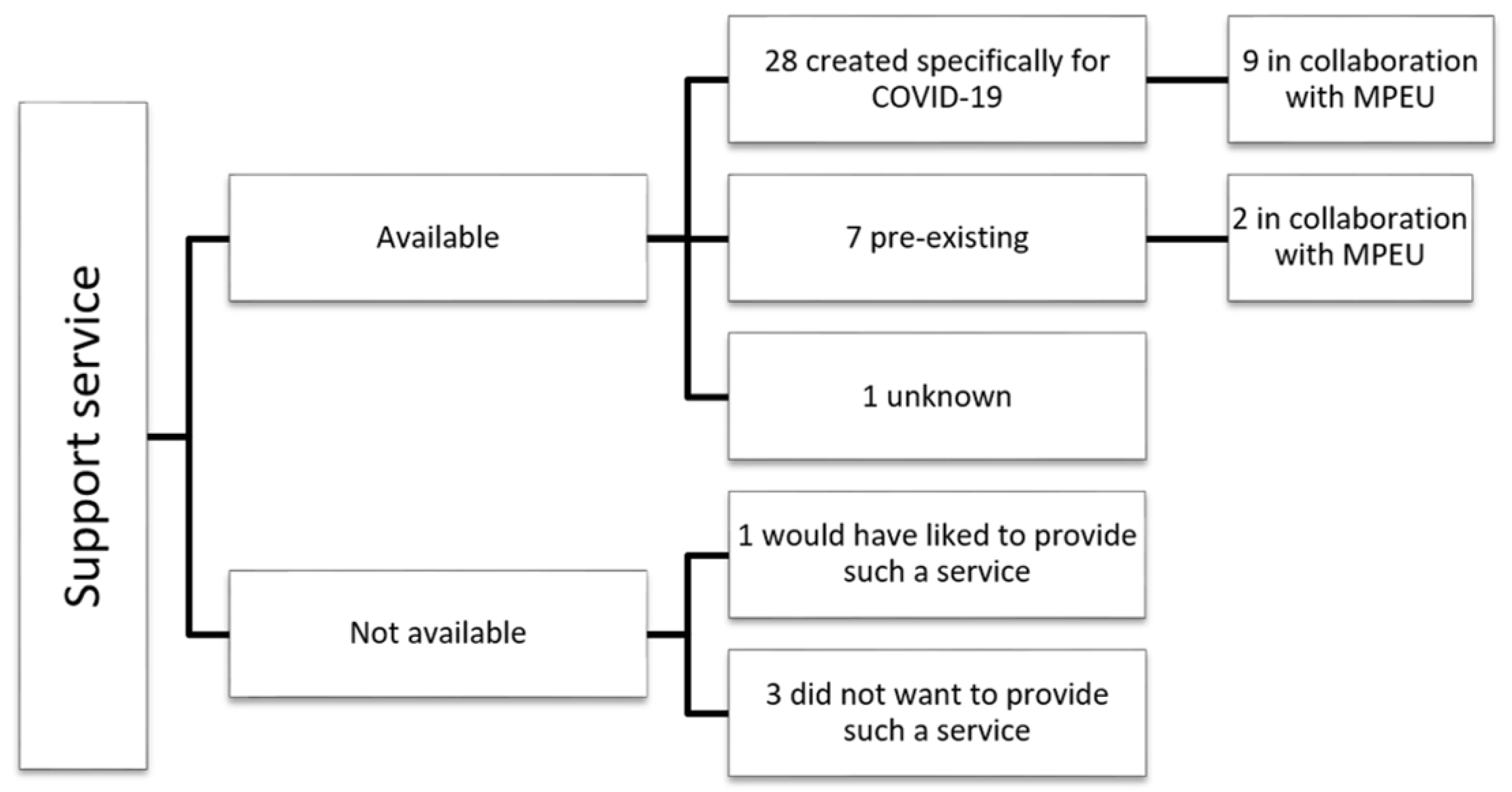

3.1. Characteristics of the Mental Health Support Services

3.2. Contact with the Chiefs of the Existing Mental Health Services

3.3. Feedback from the Service Providers

3.3.1. Working in Mental Health Support Services

3.3.2. Difficulties Encountered

- Difficulties with the work organisation

Organisation of the Service Delivery

Unusual Nature of the Work

Uncertainty

- Difficulties related to clinical situations

Refusal of Care and Under-Use of the Support Services

Non-COVID-Related Problems

Lack of Recognition for their Work

- Desire for training and avenues for improvement

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lesieur, O.; Quenot, J.P.; Cohen-Solal, Z.; David, R.; De Saint Blanquat, L.; Elbaz, M.; Gaillard Le Roux, B.; Goulenok, C.; Lavoué, S.; Lemiale, V.; et al. Admission criteria and management of critical care patients in a pandemic context: Position of the Ethics Commission of the French Intensive Care Society, update of April 2021. Ann. Intensive Care 2021, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comité Consultatif National D’éthique. COVID-19: Contribution du Comité Consultatif National D’éthique: Enjeux Ethiques Face à Une Pandémie. 2020. Available online: https://www.ccne-ethique.fr/sites/default/files/reponse_ccne_-_covid-19_def.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2022).

- Galehdar, N.; Kamran, A.; Toulabi, T.; Heydari, H. Exploring nurses’ experiences of psychological distress during care of patients with COVID-19: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French Ministry for Health. Les Cellules D’urgence Médico-Psychologique (CUMP). Available online: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/systeme-de-sante-et-medico-social/securite-sanitaire/article/les-cellules-d-urgence-medico-psychologique-cump (accessed on 19 February 2022).

- Laurent, A.; Fournier, A.; Lheureux, F.; Louis, G.; Nseir, S.; Jacq, G.; Goulenok, C.; Muller, G.; Badie, J.; Bouhemad, B.; et al. Mental health and stress among ICU healthcare professionals in France according to intensity of the COVID-19 epidemic. Ann. Intensive Care 2021, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azoulay, E.; De Waele, J.; Ferrer, R.; Staudinger, T.; Borkowska, M.; Povoa, P.; Iliopoulou, K.; Artigas, A.; Schaller, S.J.; Hari, M.S.; et al. Symptoms of burnout in intensive care unit specialists facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Ann. Intensive Care 2020, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, A.; Fournier, A.; Lheureux, F.; Poujol, A.L.; Deltour, V.; Ecarnot, F.; Meunier-Beillard, N.; Loiseau, M.; Binquet, C.; Quenot, J.P. Risk and protective factors for the possible development of post-traumatic stress disorder among intensive care professionals in France during the first peak of the COVID-19 epidemic. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2022, 13, 2011603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsubaie, S.; Hani Temsah, M.; Al-Eyadhy, A.A.; Gossady, I.; Hasan, G.M.; Al-Rabiaah, A.; Jamal, A.A.; Alhaboob, A.A.; Alsohime, F.; Somily, A.M. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus epidemic impact on healthcare workers’ risk perceptions, work and personal lives. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 2019, 13, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gruber, J.; Mendle, J.; Lindquist, K.A.; Schmader, T.; Clark, L.A.; Bliss-Moreau, E.; Akinola, M.; Atlas, L.; Barch, D.M.; Barrett, L.F.; et al. The Future of Women in Psychological Science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 483–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneyd, J.R.; Mathoulin, S.E.; O’Sullivan, E.P.; So, V.C.; Roberts, F.R.; Paul, A.A.; Cortinez, L.I.; Ampofo, R.S.; Miller, C.J.; Balkisson, M.A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on anaesthesia trainees and their training. Br. J. Anaesth. 2020, 125, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seam, N.; Lee, A.J.; Vennero, M.; Emlet, L. Simulation Training in the ICU. Chest 2019, 156, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualano, M.R.; Lo Moro, G.; Voglino, G.; Bert, F.; Siliquini, R. Effects of Covid-19 Lockdown on Mental Health and Sleep Disturbances in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; McIntyre, R.S.; Choo, F.N.; Tran, B.; Ho, R.; Sharma, V.K.; et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinkevich, P.; Larsen, L.L.; Græsholt-Knudsen, T.; Hesthaven, G.; Hellfritzsch, M.B.; Petersen, K.K.; Møller-Madsen, B.; Rölfing, J.D. Physical child abuse demands increased awareness during health and socioeconomic crises like COVID-19. Acta Orthop. 2020, 91, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boserup, B.; McKenney, M.; Elkbuli, A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 2753–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.M. An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2020, 2, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, M.; Marano, G.; Lai, C.; Janiri, L.; Sani, G. Danger in danger: Interpersonal violence during COVID-19 quarantine. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 113046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, L.; Bourquin, C.; Froté, Y.; Stiefel, F.; Saillant, S. When hotlines remain cold: Psychological support in the time of pandemic. Ann. Med. Psychol. 2021, 179, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Joboory, S.; Monello, F.; Bouchard, J.P. PSYCOVID-19, psychological support device in the fields of mental health, somatic and medico-social. Ann. Med. Psychol. 2020, 178, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, A.E.; Hafstad, E.V.; Himmels, J.P.W.; Smedslund, G.; Flottorp, S.; Stensland, S.; Stroobants, S.; Van de Velde, S.; Vist, G.E. The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: A rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Iglesias, J.J.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Martín-Pereira, J.; Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Ayuso-Murillo, D.; Martínez-Riera, J.R.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) on the mental health of healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2020, 94, e202007088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Guo, L.; Yu, M.; Jiang, W.; Wang, H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, H. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers’ mental health. Jaapa 2020, 33, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maunder, R.G.; Lancee, W.J.; Balderson, K.E.; Bennett, J.P.; Borgundvaag, B.; Evans, S.; Fernandes, C.M.; Goldbloom, D.S.; Gupta, M.; Hunter, J.J.; et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1924–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, N.; Docherty, M.; Gnanapragasam, S.; Wessely, S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020, 368, m1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laurent, A.; Fournier, A.; Poujol, A.L.; Deltour, V.; Lheureux, F.; Meunier-Beillard, N.; Loiseau, M.; Ecarnot, F.; Rigaud, J.P.; Binquet, C.; et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare professionals in intensive care. Méd. Intensive Reanim. 2021, 30, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1367–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hage, W.; Hingray, C.; Lemogne, C.; Yrondi, A.; Brunault, P.; Bienvenu, T.; Etain, B.; Paquet, C.; Gohier, B.; Bennabi, D.; et al. Health professionals facing the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: What are the mental health risks? Encephale 2020, 46, S73–S80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delelis, G.; Christophe, V.; Berjot, S.; Desombre, C. Are Emotional Regulation Strategies and Coping Strategies Linked? Bull. De Psychol. 2011, 515, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, A.; Campbell, P.; Cheyne, J.; Cowie, J.; Davis, B.; McCallum, J.; McGill, K.; Elders, A.; Hagen, S.; McClurg, D.; et al. Interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic: A mixed methods systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 11, CD013779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, F. Prevalence of self-reported depression and anxiety among pediatric medical staff members during the COVID-19 outbreak in Guiyang, China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 113005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibragimov, K.; Palma, M.; Keane, G.; Ousley, J.; Crowe, M.; Carreño, C.; Casas, G.; Mills, C.; Llosa, A. Shifting to Tele-Mental Health in humanitarian and crisis settings: An evaluation of Médecins Sans Frontières experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Confl. Health 2022, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragioti, E.; Li, H.; Tsitsas, G.; Lee, K.H.; Choi, J.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y.J.; Tsamakis, K.; Estradé, A.; Agorastos, A.; et al. A large-scale meta-analytic atlas of mental health problems prevalence during the COVID-19 early pandemic. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 94, 1935–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.E.; Harris, C.; Danielle, L.C.; Boland, P.; Doherty, A.J.; Benedetto, V.; Gita, B.E.; Clegg, A.J. The prevalence of mental health conditions in healthcare workers during and after a pandemic: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 1551–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, E.F.; Eugene, D.; Ingabire, W.C.; Isano, S.; Blanc, J. Rwanda’s Resiliency During the Coronavirus Disease Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 589526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Staffed by… | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Psychologists | 35 | 95.7 |

| From within the same hospital only | 28 | 80 |

| From outside establishments | 2 | 5.7 |

| From private practice only | - | - |

| Mixed | 5 | 14.3 |

| Psychiatrists | 17 | 47.2 |

| From within the same hospital only | 14 | 82.3 |

| From outside establishments | 1 | 5.9 |

| From private practice only | 1 | 5.9 |

| Mixed | 1 | 5.9 |

| Target audience of the support services | ||

| Healthcare workers only | 7 | 19.4 |

| Healthcare workers and patients’ families | 27 | 75 |

| Unknown | 2 | 5.6 |

| Healthcare workers targeted | ||

| Intensive care healthcare workers only | 2 | 5.6 |

| All healthcare workers in the hospital | 23 | 63.8 |

| All healthcare workers inside and outside the hospital (e.g., private practice, nursing homes) | 9 | 25 |

| Unknown | 2 | 5.6 |

| Means of contact | ||

| Telephone call centre | 33 | 91.7 |

| Web-based service | 3 | 8.3 |

| Region of Work | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Greater Eastern region of France | 21 | 57 |

| Rest of Metropolitan France | 16 | 43 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 28 | 76 |

| Male | 9 | 24 |

| Age category | ||

| 20–34 years | 9 | 24.3 |

| 35–49 years | 16 | 43.3 |

| 50–65 years | 12 | 32.4 |

| Profession | ||

| Psychologist | 25 | 67.6 |

| Physician | 8 | 21.6 |

| Nurse | 4 | 10.8 |

| Number of years of professional experience | ||

| <5 years | 6 | 16.2 |

| 5 to 10 years | 5 | 13.5 |

| >10 years | 26 | 70.3 |

| Usual place of work | ||

| Hospital | 36 | 9.3 |

| Specialised psychiatric hospital | 8 | 22.2 |

| University teaching hospital | 19 | 52.8 |

| Not specified | 9 | 25 |

| Missing data | 1 | 2.7 |

| Specific training in… | ||

| Medico-psychological emergencies | 18 | 48.6 |

| Occupational health | 4 | 10.8 |

| First time working on a helpline | ||

| Yes | 32 | 86.5 |

| No | 5 | 13.5 |

| I would do it again | ||

| Yes | 35 | 94.6 |

| No answer | 2 | 5.4 |

| Additional training would be useful to me | ||

| Yes | 22 | 59.5 |

| No | 10 | 27.0 |

| No answer | 5 | 13.5 |

| Services offered |

|---|

|

| Daily functioning |

|

| Access/Availability |

|

| Care provided |

|

| For the persons staffing the service |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loiseau, M.; Ecarnot, F.; Meunier-Beillard, N.; Laurent, A.; Fournier, A.; François-Purssell, I.; Binquet, C.; Quenot, J.-P. Mental Health Support for Hospital Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Characteristics of the Services and Feedback from the Providers. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071337

Loiseau M, Ecarnot F, Meunier-Beillard N, Laurent A, Fournier A, François-Purssell I, Binquet C, Quenot J-P. Mental Health Support for Hospital Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Characteristics of the Services and Feedback from the Providers. Healthcare. 2022; 10(7):1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071337

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoiseau, Mélanie, Fiona Ecarnot, Nicolas Meunier-Beillard, Alexandra Laurent, Alicia Fournier, Irene François-Purssell, Christine Binquet, and Jean-Pierre Quenot. 2022. "Mental Health Support for Hospital Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Characteristics of the Services and Feedback from the Providers" Healthcare 10, no. 7: 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071337

APA StyleLoiseau, M., Ecarnot, F., Meunier-Beillard, N., Laurent, A., Fournier, A., François-Purssell, I., Binquet, C., & Quenot, J.-P. (2022). Mental Health Support for Hospital Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Characteristics of the Services and Feedback from the Providers. Healthcare, 10(7), 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071337